* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Momentum and Investor Sentiment

Algorithmic trading wikipedia , lookup

Short (finance) wikipedia , lookup

Securities fraud wikipedia , lookup

Technical analysis wikipedia , lookup

Stock market wikipedia , lookup

Stock exchange wikipedia , lookup

2010 Flash Crash wikipedia , lookup

Efficient-market hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

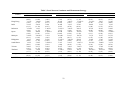

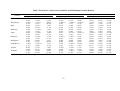

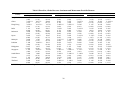

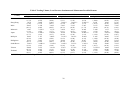

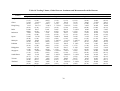

Momentum and Investor Sentiment : Evidence from Asian Stock Markets Shangkari V.Anusakumar Universiti Sains Malaysia School of Management USM, 11800 Penang, MALAYSIA [email protected] Tel: +(604) 6533984 Ruhani Ali Universiti Sains Malaysia Graduate School of Business USM, 11800 Penang, MALAYSIA [email protected] Tel: +(604) 6533954 Hooy Chee Wooi Universiti Sains Malaysia School of Management USM, 11800 Penang, MALAYSIA [email protected] Tel: +(604) 6532897 Momentum and Investor Sentiment : Evidence from Asian Stock Markets Abstract The study provides the first evidence on the effect of investor sentiment on momentum profitability in Asia. A sample of 13 Asian countries is analysed over a period of 12 years from January 2000 to December 2011. We find that momentum arises only during optimistic and mild periods. Momentum is conspicuously absent for periods of pessimism. The evidence suggests that investors are detail oriented during pessimistic periods and thereby hinder the occurrence of momentum in the stock market. In addition to local sentiment, we also find that global sentiment affects momentum which affirms the contagious nature of sentiment. The results are robust to changes in sentiment period classification and use of alternative proxies. Moreover, we also find that the findings are unaffected after taking into consideration firm size and trading volume. Keywords: Momentum, Sentiment, Global Sentiment, Asian markets 1 1 Introduction Within the large body of literature that documents return predictability, the momentum effect is arguably one of the most important and intriguing. It is one the few anomalies that have yet to be explained in its entirety. In fact, Fama (1998) acknowledged momentum as one of the most difficult anomalies to account for. The momentum effect was first documented by Jegadeesh and Titman (1993). The authors demonstrated that stocks which performed poorly (well) in the past continue to perform poorly (well) in the future. The basic concept of momentum strategy is to buy ‘winners’ (stocks that performed well in the past) and sell ‘losers’ (stocks that performed poorly in the past). Sentiment is proposed as one of the factors that could affect the levels of momentum. Investor sentiment, as proxied by consumer confidence index, has been shown to influence future stock returns (Schmeling, 2009). Higher sentiment is linked to a lower stock returns in the future. However, the predictive power of sentiment ranges from strong to none depending on the stock market being investigated. A variety of studies have surged linking sentiment and other financial aspects from IPO prices to feedback trading (e.g. Ben-Rephael, Kandel & Wohl, 2011; Chau, Deesomsak & Lau, 2011; Cornelli, Goldreich & Ljungqvist, 2006; Küçükaslan & Çelik, 2010; Liao, Huang & Wu, 2011). For momentum, Antoniou, Doukas and Subrahmanyam (2012) found higher momentum during periods of high investor sentiment compared to low sentiment and that sentiment is absent during pessimistic periods. As highlighted by Schmeling (2009), the effect of sentiment varies from country to country, and as such the relationship between momentum and sentiment needs to be reexamined in Asian markets. Investor sentiment was found to be related to momentum in the US (Antoniou et al., 2012) but this relationship may or may not hold in Asia. Firstly, manifestation of momentum in Asia drastically differs from other regions around the world (Griffin et al., 2003). So much 2 so that Hameed and Kusnadi (2002) argued that the factors that drive momentum in Asia may not be the same as those in the US. More importantly, the psychology of Asians are notably distinct from Westerners including reasoning (Buchtel & Norenzayan, 2008) and modes of thinking (Nisbett, 2003). Hedden, Ketay, Aron, Markus, and Gabrieli (2008) showed that individuals from America and Asia have distinct brain activity patterns when exposed to the same visual problems. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans revealed higher brain activity for Americans when solving problems involving relative judgement compared to absolute judgment. On the other hand, the reverse was true for East Asians. Given these clear distinctions, the question arises as to whether the sentiment would still be related to momentum in Asia and if so what would be the nature of the relationship. To the best of our understanding, the first and thus far the only study specifically on sentiment and momentum was conducted by Antoniou et al. (2012) for the US market. Needless to say, the literature is very sparse. International evidence in support or against the existing results would provide much needed insight into the issue. In addition to this, global sentiment and sentiment during portfolio holding period is also hypothesized to have an effect on momentum returns and is investigated accordingly. Not only does this thesis provide out-of-sample evidence, it also expands the study of sentiment to incorporate global investor sentiment. Sentiment represents the state of mind of the investors. From a psychological viewpoint, investors’ decision to buy, sell or hold would be influenced by the investor’s psychological state at that point in time. Decision making is not undertaken in isolation, thus emotional state could sway trading behaviour of investors. The effect would then translate into either a detrimental or additive factor on the propensity to commit cognitive biases. In a positive state, individuals are more likely to stick to their normal routine but negative state elicits a more severe response whereby processing is more detail oriented (Schwarz, 2002). 3 Ali and Gurun (2009) also echoed the view that optimism decreases the attentiveness of investors. To surmise, individuals are more alert during pessimistic periods and less attentive at optimistic times. Inattentiveness causes a delayed reaction to the arrival of new information supporting behavioural theories of underreaction (Dellavigna & Pollet, 2009). As for pessimistic periods, the increased awareness and processing of information could reduce or even remove the cognitive bias that drives momentum. Thus, it could be conjectured that optimism leads to a higher level of momentum whereas pessimism is associated with lower or even absence of momentum. In addition to sentiment in the local stock market, cognitive biases and correspondingly momentum returns could be swayed by sentiment on an international scale. Baker, Wurgler and Yuan (2012) also advocated the view and demonstrated the influence of global sentiments on stock prices. Moreover the authors suggested that 'sentiment is contagious across markets'. Chang, Faff and Hwang (2009) suggested that US investor sentiment may reflect global sentiments. Investigating 38 countries, the authors documented strong sentiment contagion. Thus it is not a stretch to postulate that global investor sentiment, apart from local sentiment, would affect stock momentum in Asia. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. We describe the data source and methodology in Section 3 and 4 respectively. In Section 5, we provide the results and discussion. Finally Section 5 provides the conclusion. 2 Data The study encompasses a 12-year period from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2011. This particular period is examined in the interest of using up to date information to reflect current market conditions. The premise of this study is Asian stock markets. As the sample time period covers the years 2000 to 2011, stock exchanges newly founded for this duration could not be included in the sample. This excludes stock exchanges established from 2000 onwards 4 such as the Hochiminh Stock Exchange (HOSE) in Vietnam. As in Griffin et al. (2005), a minimum of 50 stocks are required to be listed on the stock exchange to enable momentum and subsequent tests to be carried out. This restriction weeds out exchanges with limited listings such as the Maldives Stock Exchange (MSE). The screening results in a final sample of stock exchanges from 13 Asian countries: Bangladesh, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand. Stock return index is obtained from Datastream. In addition to stock return data, trading volume, firm size, consumer confidence indices and other related information are also obtained from Datastream. Table 1 states the sample countries used in this study and also presents the total number of sample stocks for each country. This figure includes active and ‘dead’ (delisted) stocks. The number of stocks available at each juncture for portfolio formation and holding differs from this figure. The consumer confidence index has been frequently used a proxy for investor sentiment (Lemmon & Portniaguina, 2006). The sentiment index is constructed based on survey information. The questionnaire and frequency of data collection differs from country to country. Nevertheless it is a reliable and independent source for the measurement of sentiments. An advantage of using the consumer confidence index is the fact that the values are derived independently of the stock market. Measures derived from stock market related data could be compounded by a multitude of factors. Therefore a proxy independent of the stock market is needed. Consumer confidence index provides such a measure as it is based on direct survey of individual consumers and is thus free from stock market related factors. Moreover as stated by Schmeling (2009), consumer confidence index “seems to be the only consistent way to obtain a sentiment proxy that is largely comparable across countries” (p. 397). Consumer confidence index available for each country is obtained from Datastream. 5 Following Chang et al. (2009), global sentiment is proxied by US investor sentiment. For this purpose, a US based consumer confidence index is used to gauge the global investor sentiments. The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index has been used to measure investor sentiment in several recent US market based studies (e.g. Ho and Hung, 2009; Tang and Yan, 2010). Moreover, Qiu and Welch (2004) and Lemmon and Portniaguina (2006) have noted that the consumer confidence index is appropriate measure of investor sentiment. The index is formed based on a monthly survey of 5000 households in the US. 3 Methodology The 6 month formation and 6 month holding period strategy has been found to be consistently profitable (Jegadeesh & Titman, 1993) and is frequently used in literature. Stocks are ranked based on cumulative returns from t-2 to t-7. Equally weighted winner and loser portfolios are formed using the top (winner stocks) and bottom (loser stocks) 10% of the stocks. A month is skipped after portfolio formation in order to mitigate microstructure biases. The constituents of the winner and loser portfolio are maintained for 6 months. The monthly returns for the winner, loser and momentum portfolio are computed for each month from t to t+5. The procedure is repeated for each month. At the end of formation period t, the weighted rolling average consumer confidence index of the previous 3 months is calculated with the weight of 3, 2 and 1 for month t, t-1 and t-2 respectively. AvgSent = 1 2 3 Sent t − 2 + Sent t −1 + Sent t 6 6 6 AvgSent is the weighted average sentiment used to classify formation periods as pessimistic or optimistic. Sentt-2, Sentt-1 and Sentt represent confidence index value at month t-2, t-1 and t respectively. 6 A particular formation period's sentiments is high/optimistic (low/optimistic) when it ranks in the top (bottom) 30% of the average sentiment values. The remaining portfolios are assumed to have been formed during a ‘mild’ period i.e. neither high nor low level of sentiment. The cut off is the same as that employed by Antoniou et al. (2012). Periods of high and low investor sentiment are thus defined on a relative basis for the entire sample period. Following this, the momentum returns for the portfolios formed during pessimistic, mild and optimistic periods are assessed. For local sentiment, the consumer confidence index for each country is used for the aforementioned analysis. Apart from local sentiment, the stock market returns could be swayed by global sentiments. Stock markets are no longer closed entities; the participants of stocks markets are comprised of a broad range of investors from various countries. Global sentiment has been shown to effect stock prices apart from local sentiment (refer to Baker et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009). For global sentiment, the procedure is performed using Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index. 4 4.1 Empirical Results Momentum Returns for Asian Markets Table 2 presents the average monthly returns along with corresponding t-statistics for winner, loser and momentum portfolio for the 13 countries. As in Chui et al. (2010), the final row reports the averages. The portfolios are formed monthly by sorting the stocks based on the past 6 month returns. The stocks in the best performing decile is designated as winners and worst decile are designated as losers. Winner and loser portfolios are then formed using the selected stocks. Momentum portfolio is constructed by taking a long position in the winner stocks and a short position in the loser stocks. Winner, loser and momentum portfolios are held for the following six months after skipping one month to eliminate market 7 microstructure biases (as is the convention in momentum studies). Momentum returns are computed as the differential between winner and loser portfolio returns. The winner portfolio generates positive return for all of the countries. The returns are statistically significant for a majority of the countries, specifically for nine out of the thirteen the countries. This provides evidence of significant return continuations for winner stocks. In other words, stocks that performed well in the past continue to perform well in the future. In contrast, loser portfolio returns are significant for only six countries. Returns to the momentum portfolio are generally positive. Out of the sample of 13 countries, 11 countries have positive returns for the momentum portfolio while 2 countries have negative returns. The highest momentum can be observed for Bangladesh whilst Philippines has the lowest return. Roughly one third of the sample countries display statistically significant momentum. Certain countries exhibit a high degree of momentum comparable to those reported in the US market. In short, there is evidence of momentum profitability in selected Asian countries. Bangladesh, in particular, has markedly strong momentum in the stock market. The momentum portfolio earns 1.470% per month which is higher than the returns reported in the US (e.g. Jegadeesh and Titman, 2001). The winner and loser portfolios both generate significant returns on their own. In particular, the winner portfolio has noticeably strong returns. The findings of momentum in Bangladesh concur with the results of Chui et al. (2011). As indicated by the last row of Table 2, on average, there is significant momentum in Asia at the 5 percent level. 4.2 Momentum and Local Sentiment Table 3 reports the portfolio returns for the momentum strategy during three sentiment states: optimistic, mild and pessimistic. Sentiment states classification is done based on the weighted average of local consumer confidence index values over the portfolio formation period. The 8 average monthly returns, in percentages, are presented for the winner, loser and momentum portfolio along with the associated t-statistics. Due to unavailability of local sentiment data, the effect of local sentiment on momentum could not be explored for Bangladesh, Singapore and Pakistan. As can be observed from Table 3, the non-existence of momentum for pessimistic periods is glaringly obvious. As hypothesized by Antoniou (2012), none of the thirteen countries display any momentum for the pessimistic period. Momentum exists exclusively in the optimistic and mild periods. Further solidifying the failure of momentum strategy during pessimistic times, there are instances where returns for the pessimistic period are outright negative whereas optimistic periods have strong positive returns. For example, the strategy in the Japanese markets undergoes statistically significant losses of 2.599% on a monthly basis for pessimistic period. At the other end of the spectrum, the momentum portfolio in the optimistic period garners a substantial monthly return of 1.280% which is statistically significant at the 1 percent level. This highlights the stark variation in momentum between the sentiment states. Another notable finding is the presence of momentum during optimistic and mild periods in countries where otherwise momentum could not be found. Indonesia, Japan and Taiwan have no momentum for the overall strategy but record high and statistically significant returns to the momentum portfolio for the optimistic and/or mild period. Thus, it could be conjectured that sentiment state is one the factors causing the apparent lack of momentum or rather masking the presence of momentum in Asia. A salient fact emerges from this study; sentiment does influence momentum profitability. The most striking result can be observed for Japan. Whilst studies have reported contradictory account of momentum levels in other markets such as Hong Kong, the Japanese stock market has always been reported to be devoid of momentum and returns are often 9 negative. The earlier part of this thesis also supports the notion that there is no momentum in Japan. Surprisingly, there are high levels of momentum once sentiment in taken into account. Returns for momentum strategy is high during optimistic and mild periods but is downright unprofitable during pessimistic periods. There is a staggering return differential of 3.879% between optimistic and pessimistic periods. The evidence suggests that sentiment could be the reason for the absence of momentum in Japan. A similar account could be noted for Taiwan, another country where momentum has been chronically non-existent. Overall, the evidence on local sentiment concurs with the findings of Antoniou et al. (2012); momentum is only present for high sentiment periods. Momentum portfolio returns are in part derived from the poor performance of the loser portfolio. The factor that differentiates high and low sentiment periods is largely the loser portfolio. Loser portfolio returns are higher during pessimistic periods compared to optimistic periods. Moreover, returns for loser portfolio are on par with or higher than winner portfolio for low sentiment states. It is this fact that causes the absence of momentum during pessimistic periods. The evidence suggest that investor’s have a greater propensity to engage in detailed processing during low sentiment periods which causes the elimination of momentum during pessimistic periods (Schwarz, 2002). 4.3 Momentum and Global Sentiment Table 4 reports the winner, loser and momentum portfolio returns, along with the t-statistics, during periods of varying global sentiment. The sentiment periods are split into optimistic, mild and pessimistic based on the past index values that rank in the top 30%, middle 40% and bottom 30% respectively. The portfolio return figures are in percentage and represent the average monthly return. 10 Momentum portfolio returns are positive for all countries during the optimistic period, out of which five countries have significant returns. For the mild period, six countries have significant returns whilst there are no significant returns for the pessimistic period. Overall, eight of the thirteen countries have significantly positive returns to the momentum portfolio during the optimistic and/or mild period. The highest momentum portfolio return reaches up to 2.904% per month. In other words, more than half of the Asian countries exhibit strong momentum. One of the main and apparent finding is that the pessimistic period is devoid of momentum. In this aspect, the evidence reconciles with the findings of the preceding section where local investor sentiment was investigated. Furthermore, almost all of the countries, eleven of the thirteen countries, have negative returns to the momentum portfolio. This presents overwhelming evidence on the failure of momentum strategy during periods of low sentiment. In contrast, momentum strategy fares better for the other sentiment states especially optimistic periods. Momentum is undoubtedly the highest during optimistic periods. Moreover countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan have significant returns only during optimistic periods. Momentum in optimistic periods outperforms pessimistic periods primarily due to the loser portfolio. For the optimistic periods, the loser portfolio performs poorly as expected. However the loser portfolio performs comparatively better in during pessimistic periods. For example, Bangladesh has a measly loser portfolio return of 0.035% for optimistic period but the fortunes of the loser portfolio changes drastically during pessimistic period as the average monthly return is 2.880% and is marginally significant. Last but not least, there are countries which display strong momentum for high sentiment states but do not have any momentum for the overall momentum strategy. This evidence is again similar to that found for the local investor sentiment. China, Singapore and Thailand did not have any significant momentum for the unrestricted strategy (Table 2). 11 Upon segregating momentum based on global sentiment, these countries display high levels of momentum. For instance, China has statistically significant monthly return of 1.288% (1.019%) for the optimistic (mild) period. However for the overall strategy China had an insignificant and comparatively meager return of 0.555% per month (Table 2). Global sentiment appears to have a stronger effect on momentum than local sentiment. An extreme example of this is the Chinese stock market. Momentum in China is unaffected by local sentiment i.e. there is no momentum in the market regardless of the sentiment state. However significant returns emerge when global sentiment is used for the analysis. As the evidence suggests that global sentiment may have an equal if not greater influence on momentum profitability, investors should pay heed to both local and global sentiment when implementing in the momentum strategy in Asian markets and in some cases more to the latter. In a nutshell, global sentiment also affects momentum profitability. This finding corroborates with the contagious nature of sentiment as noted by Baker et al. (2012). It is has been suggested that sentiment spreads rapidly through mass media (Du, 2010). Baker et al. (2012) suggested that “capital flows are a key mechanism through which global sentiment develops and propagates, but there are surely others, including word-of-mouth and the media” (pg. 104). Regardless of the means by which sentiment spreads, the fact that global sentiment affects the level of momentum profitability in Asian markets further confirms the contagious nature of investor sentiment. 4.4 Alternative Sentiment Classification The investor sentiment investigations thus far have been conducted by classifying sentiment period based on a 30% cut off. A period is optimistic (pessimistic) if the index value is in the top 30% (bottom) of the time series of sentiment index values. Remaining periods are designated as mild periods. In this section, an alternative sentiment cut-off is selected and 12 investigated to ensure the findings of this study are robust to changes in sentiment classification. Specifically the analysis is repeated using a 40% cut-off for sentiment classification. Table 5 reports the results of this analysis1. For local sentiment, the findings are similar with the use of a 40% cutoff for sentiment classification instead of 30% cut off. Pessimistic periods are devoid of momentum; none of the thirteen countries exhibit statistically significant returns to the momentum portfolio during pessimistic periods. During optimistic and mild periods, there are countries that display high levels of profitability. For example, Japan has a return of 1.025% during optimistic periods, which is comparable to the momentum levels reported in US. In contrast, momentum portfolio return in Japan during pessimistic period is an insignificant -1.239%. In short, there’s a return difference of 2.264% between optimistic and pessimistic period. Investigation using 40% cut off for global sentiment also echoes the earlier findings. There is a clear divide between profitability during pessimistic periods and periods with higher sentiment. Returns to the momentum strategy are rampantly negative for pessimistic periods. Moreover the negative return for Japan is statistically significant indicating that an investor implementing a momentum strategy during global pessimistic periods would stand to a 1.176% per month. In contrast, an investor implementing the strategy during optimistic periods could gain an average monthly return of 1.341%. High momentum profitability could be found in selected countries during high sentiment periods. Bangladesh, for example, offers a high momentum portfolio return of 2.101% (significant at 5 percent level) for optimistic periods. Overall, the earlier findings are generally intact irrespective of the sentiment classification. 1 For brevity, only optimistic and pessimistic momentum returns are reported. Full results are available upon request. 13 4.5 Alternative Sentiment Proxies For robustness, we repeat the sentiment analysis using an alternative sentiment measure, University of Michigan Sentiment Index. In addition to the survey based sentiment measure, sentiment index by Baker and Wurgler (2006) which is a market based measure is also tested in this section. Table 6 reports the results of the study using the alternative sentiment measures. Firstly, results for the analysis using the University of Michigan Sentiment Index is presented. Eight of the thirteen countries have significant momentum during optimistic and/or mild periods. Momentum strategy performs poorly during pessimistic periods as there are no significant returns; the returns are also largely negative. The failure of momentum strategy during pessimistic periods is clearly visible. Thus, the earlier conclusion that sentiment affects momentum remains unaltered with the use of the alternative sentiment proxy, University of Michigan Sentiment Index. For the Baker and Wurgler (2006) index, the results are sporadic. There are only two countries with momentum during optimistic periods. Moreover, only marginally significant momentum is present for mild period whereas there are highly significant momentum for two countries and one marginally significant negative return during pessimistic period. There appears to be no detectable pattern. Given that momentum is equally present in optimistic periods and pessimistic periods, this leads to the conclusion that momentum is not affected by sentiment as measured by the Baker and Wurgler (2006) index. The lack of evidence could be due to the nature of the Baker and Wurgler (2006) index. The index is derived from variables from the stock market such as returns on first day returns on IPO. On the other hand, Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index and University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index are survey based measure where the index is constructed based on direct 14 survey of consumers. The results suggest that the Baker and Wurgler (2006) index may not be able to fully capture the components of global sentiment. An alternative survey based measure, University of Michigan sentiment index, produces a similar, if not stronger results. On the other hand, the analysis with Baker and Wurgler (2006) composite index yields sporadic momentum across the sentiment states with no obvious pattern. This is at odds with the results of Antoniou et al. (2012) where results were similar whether consumer confidence index by Conference Board (proxy used throughout the study) or the Baker and Wurgler (2006) composite index (alternative proxy tested for robustness) were used for the analysis. It is possible that the while Baker and Wurgler (2006) composite index is an sufficient proxy for the local US market, the index poorly captures global sentiment. Moreover, Conference Board consumer confidence index and University of Michigan sentiment index is a survey based proxy of sentiment which may provide an edge over the composite index which is derived from market based variables. 4.6 Momentum, Sentiment and Size In this section, the robustness of the effect of sentiment on momentum is further tested by analyzing size. The effect of local sentiment on momentum for the size categories is reported in Table 7. The effect of investor sentiment on momentum persists irrespective of the firm size. In each size category, large, medium and small, a distinct pattern can be observed across the sentiment states; momentum is strong in optimistic and mild period whereas pessimistic periods have little or no momentum. In fact, the returns to the momentum portfolio are generally negative in the pessimistic period for the three size categories. This is readily apparent for Japan where momentum is present only for optimistic and mild periods and turns significantly negative for pessimistic period. For example, the medium stock category for Japan has statistically significant returns of 1.020%, 0.772% and -2.531% per month for optimistic, mild and pessimistic period respectively. 15 The effect of global sentiment on momentum for the size categories is reported in Table 8. Again, momentum returns for the large, medium and small stocks are all greatly affected during times of global pessimism. There are primarily negative returns for the momentum portfolio throughout the three size categories for the pessimistic period. Small stocks suffer the most as evidenced by the statistically significant negative returns (in two instances). For example, investors focusing momentum strategy on small stocks stand to lose a staggering 2.788% per month during globally pessimistic periods. Small stocks do not perform as well as large and medium stocks generating comparatively lower momentum portfolio returns. Moreover, the presence of statistically significant momentum is largely concentrated in large and medium stocks during optimistic and mild periods. 4.7 Momentum, Sentiment and Volume In this section, the robustness of the effect of sentiment on momentum is further tested by analyzing trading volume. Trading volume may contain an element of investor sentiment (Baker & Wugler, 2006). Optimistic investors are more likely to engage in trading activity in a market with short-sales constraints and this activity is reflected in trading volume and generally in liquidity (Baker & Stein, 2004). In a sense, trading volume may reflect investor sentiment but trading volume in itself is a simple and imperfect proxy of sentiment as it is confounded by factors unrelated to sentiment. At the end of each formation period, the stocks are segregated into three volume portfolios; high, medium and low. Then winner, loser and momentum portfolios are formed, by ranking stocks on the past six month return, within the three volume categories. Finally the portfolios are classified as optimistic, mild or pessimistic according to the average confidence index value. The monthly momentum returns for these triple sorted portfolios are then computed. 16 Table 9 reports the results of this robustness analysis for local sentiment. The results concur with those of Section 4.2, pessimistic period is largely devoid of momentum while optimistic and mild period have instances of strong momentum. Momentum in all three volume categories appear to be affected by local sentiment. For example, high volume stocks in Japan have a high significant return of 1.733% during optimistic period but this figure dramatically drops to -2.112 during pessimistic periods. Low volume stocks show a similar decrease in momentum as sentiment drops with statistically significant returns of 0.855%, 0.765% and -2.049% for optimistic, mild and pessimistic periods respectively. The earlier remarkable finding of momentum in Japan for high sentiment periods still holds and is perhaps stronger after taking into account trading volume. In order to examine the robustness of the effect of global sentiment on momentum across volume categories, the aforementioned analysis is repeated using the proxy for global investor sentiment index. Table 10 reports the results of this analysis. Momentum portfolio returns are all insignificant for global pessimistic periods for all of the volume categories. The only exception is the medium volume category for China and even then the momentum portfolio return is negative with marginally significant return of -1.079%, indicating that investors could face substantial loses during pessimistic periods. On the other hand, there are momentum portfolio returns as high as 3.546% for global optimistic and mild periods. Significant momentum can be observed for all three categories. For example, high volume stocks in South Korea yield 1.495% per month during mild periods whereas returns are approximately 2% for medium volume stocks; low volume stocks are also profitable with momentum portfolio returns of 1.610% The evidence indicates that momentum is affected by global sentiment irrespective of trading volume. 17 5 Conclusion The central finding of this study is that sentiment affects momentum profitability in Asia. Momentum is present only during optimistic and mild periods. Pessimistic periods are fraught with negative returns. More importantly, countries where there is persistent absence of momentum display significant momentum once sentiment in taken into account. Japan, for example, has significant momentum during states of high sentiment. On the other hand, significant negative returns to the momentum portfolio is present during pessimistic periods. This is what deprives these markets of momentum. In addition to the local sentiment prevalent in the market, sentiment on a global scale influences momentum. In some cases, global sentiment appears to have a greater effect on momentum compared to local momentum. Moreover the findings are robust to changes in the classification of sentiment periods and alternative sentiment and even after taking into account firm size and trading volume. Bottom-line is that momentum is absent during pessimistic periods. The findings provides an interesting revelation to investors. Whilst higher sentiment periods provide investors with significant momentum portfolio returns, pessimistic periods do not yield any significant returns and in some cases could even lead to substantial losses. Investors seeking to implement momentum strategy in Asia and possibly elsewhere should be cautious of the sentiment prevalent at the time of portfolio formation. Moreover global sentiment should be taken into consideration as well. Implementing momentum strategy during consistently pessimistic periods could prove to be disastrous. The message is clear: investors should stand clear of pessimistic periods. However, it should be noted that trading costs have not been taken into account and this area could be an interesting consideration for future papers. 18 References Ali, A., & Gurun, U. G. (2009). Investor Sentiment, Accruals Anomaly, and Accruals Management. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 24(3), 415 - 431. Antoniou, C., Doukas, J. A., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2012). Sentiment and Momentum. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Forthcoming. Baker, M., & Stein, J. C. (2004). Market liquidity as a sentiment indicator. Journal of Financial Markets, 7(3), 271-299. Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor Sentiment and the Cross-Section of Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645-1680. Baker, M. P., Wurgler, J. A., & Yuan, Y. (2012). Global, Local, and Contagious Investor Sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 104, 272-287. Ben-Rephael, A., Kandel, S., & Wohl, A. (2011). Measuring investor sentiment with mutual fund flows. Journal of Financial Economics, In Press, Corrected Proof. Buchtel, E. E., & Norenzayan, A. (2008). Which should you use, intuition or logic? Cultural differences in injunctive norms about reasoning. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(4), 264-273. Chang, C., Faff, R. W., & Hwang, C.-Y. (2009). Sentiment Contagion, Corporate Governance, Information and Legal Environments (Working paper). Chau, F., Deesomsak, R., & Lau, M. C. K. (2011). Investor sentiment and feedback trading: Evidence from the exchange-traded fund markets. International Review of Financial Analysis, In Press, Accepted Manuscript. Chui, A. C. W., Titman, S., & Wei, K. C. J. (2010). Individualism and Momentum around the World. The Journal of Finance, 65(1), 361-392. Cornelli, F., Goldreich, D., & Ljungqvist, A. (2006). Investor Sentiment and Pre-IPO Markets. The Journal of Finance, 61(3), 1187-1216. Dellavigna, S., & Pollet, J. M. (2009). Investor Inattention and Friday Earnings Announcements. The Journal of Finance, 64(2), 709-749. Fama, E. F. (1998). Market efficiency, long-term returns, and behavioral finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 49(3), 283-306. Griffin, J., Ji, S., & Martin, S. (2005). Global Momentum Strategies: A Portfolio. Perspective. Journal of Portfolio Management, 31, 23 - 39. Griffin, J. M., Ji, X., & Martin, J. S. (2003). Momentum Investing and Business Cycle Risk: Evidence from Pole to Pole. The Journal of Finance, 58(6), 2515-2547. 19 Hameed, A., & Kusnadi, Y. (2002). Momentum Strategies: Evidence from Pacific Basin Stock Markets. Journal of Financial Research, 25(3), 383-397. Hedden, T., Ketay, S., Aron, A., Markus, H. R., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2008). Cultural Influences on Neural Substrates of Attentional Control. Psychological Science, 19(1), 12-17. Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (1993). Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency. Journal of Finance, 48, 65–91. Lemmon, M., & Portniaguina, E. (2006). Consumer Confidence and Asset Prices: Some Empirical Evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 19(4), 1499-1529. Qiu, L. X., & Welch, I. (2004). Investor Sentiment Measures, NBER Working Paper Series. Schmeling, M. (2009). Investor sentiment and stock returns: Some international evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance, 16(3), 394-408. Schwarz, N. (2002). Situated Cognition and the wisdom of feelings: Cognitive Tuning. In B. Feldman & P. Salovey (Eds.), The wisdom of feelings (pp. 144 - 166). New York: Guilford Press. 20 Table 1 Sample Description No. Country Stock Exchange Abbr. No. of Stocks 1 Bangladesh Dhaka Stock Exchange DSE 351 2 China Shanghai Stock Exchange SSE 948 3 Hong Kong Hong Kong Stock Exchange HKEX 1505 4 India Bombay Stock Exchange BSE 3101 5 Indonesia Indonesia Stock Exchange IDX 498 6 Japan Tokyo Stock Exchange TSE 2913 7 Malaysia Bursa Malaysia MYX 1052 8 Pakistan Karachi Stock Exchange KSE 447 9 Philippines Philippine Stock Exchange PSE 274 10 Singapore Singapore Exchange SGX 775 11 South Korea Korea Exchange KRX 995 12 Taiwan Taiwan Stock Exchange TSEC 926 13 Thailand Stock Exchange of Thailand SET 675 Total Sample 14,460 21 Table 2 Average monthly returns for the momentum strategy (%) Momentum Bangladesh Winner Loser Momentum Return (%) 2.829*** 1.358* 1.470** t-stat (3.76) (1.72) (2.27) China Return (%) 1.041 0.486 0.555 t-stat (1.36) (0.56) (1.50) Hong Kong Return (%) 1.301* 0.320 0.981** t-stat (1.82) (0.35) (2.06) India Return (%) 2.666*** 3.226*** -0.560 t-stat (2.97) (2.78) (-0.91) Indonesia Return (%) 1.639*** 1.363* 0.276 t-stat (3.03) (1.90) (0.55) Japan Return (%) 0.156 0.014 0.142 t-stat (0.32) (0.02) (0.43) Malaysia Return (%) 0.493 -0.260 0.753* t-stat (1.12) (-0.37) (1.71) Pakistan Return (%) 1.910*** 1.298* 0.611 t-stat (3.21) (1.72) (1.08) Philippines Return (%) 1.503** 2.442*** -0.939 t-stat (2.39) (2.87) (-1.51) Singapore Return (%) 0.964* 0.067 0.897 t-stat (1.66) (0.08) (1.65) South Korea Return (%) 1.682** 0.552 1.130** (2.32) (0.65) (2.40) Taiwan Return (%) 0.573 0.460 0.113 t-stat (0.74) (0.49) (0.24) Thailand Return (%) 1.932*** 1.347* 0.585 t-stat (3.65) (1.79) (1.13) Average Return (%) 1.438*** 0.975*** 0.463** t-stat (6.47) (3.49) (2.51) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 22 Table 3 Local Investor Sentiment and Momentum Strategy Country China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Philippines South Korea Taiwan Thailand Average Winner -0.074 (-0.06) 3.172* (1.85) -5.138 (-1.13) 2.728** (2.49) 1.182 (1.46) -3.656* (-2.11) 1.335 (0.86) 1.354 (0.93) -4.939 (-1.41) 2.145* (1.77) -0.189 (-0.19) Optimistic Loser -0.600 (-0.40) 3.066* (1.95) -5.439 (-1.38) 1.263 (1.17) -0.098 (-0.11) -5.830** (-2.66) 2.063 (1.56) -1.245 (-0.86) -5.373 (-1.55) 1.640 (1.12) -1.055 (-1.00) Mom 0.526 (1.09) 0.106 (0.17) 0.301 (0.27) 1.465** (2.46) 1.280*** (2.74) 2.174 (1.43) -0.728 (-0.66) 2.598*** (3.36) 0.434 (0.26) 0.505 (0.55) 0.866** (2.72) Winner 1.816 (1.62) -0.269 (-0.29) 0.460 (0.27) 1.619** (2.17) -0.648 (-0.90) 0.849* (1.74) 2.762** (2.33) 1.312 (1.44) 0.667 (0.57) 1.368** (2.11) 0.994** (3.12) Mild Loser 0.983 (0.75) -1.997* (-1.81) 3.162 (0.70) 2.035* (1.98) -1.203* (-1.69) -0.127 (-0.17) 2.991** (2.04) 0.105 (0.10) -1.281 (-0.95) 0.392 (0.41) 0.506 (0.90) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 23 Mom 0.833 (1.44) 1.728*** (3.64) -2.701 (-0.81) -0.416 (-0.56) 0.555* (1.68) 0.976* (1.97) -0.229 (-0.22) 1.207** (2.22) 1.947* (1.94) 0.976 (1.50) 0.488 (1.15) Winner 0.152 (0.10) 3.116** (2.38) 4.444 (1.88) 0.758 (0.68) 1.125 (1.11) 1.379 (1.47) 2.100 (1.47) 4.234** (2.26) 1.644 (0.52) 4.918*** (4.42) 2.387*** (4.49) Pessimistic Loser 0.243 (0.16) 3.013 (1.22) 3.121 (1.53) -0.101 (-0.06) 3.725* (2.02) 2.157 (1.20) 1.742 (1.55) 5.608* (2.06) 1.784 (0.65) 6.535*** (3.62) 2.783*** (4.16) Mom -0.091 (-0.14) 0.103 (0.06) 1.323 (0.79) 0.859 (0.82) -2.599** (-2.21) -0.779 (-0.70) 0.358 (0.44) -1.374 (-0.74) -0.140 (-0.22) -1.618 (-0.90) -0.396 (-1.04) Table 4 Global Investor Sentiment and Momentum Strategy Country Bangladesh China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Singapore South Korea Taiwan Thailand Average Optimistic Winner Loser 2.603 ** 0.036 (2.19) (0.03) 1.556 0.269 (1.00) (0.16) 2.132 -0.772 (1.04) (-0.32) 1.833 * 1.583 (0.77) (1.94) 1.073 -0.753 (0.72) (-0.41) -0.353 -1.390 (-0.35) (-1.06) -0.566 -1.536 (-0.43) (-0.62) 0.697 2.433 * (1.97) (0.57) 1.571 0.849 (0.87) (0.34) 0.369 -1.537 (0.25) (-0.77) 1.702 3.436 (1.58) (0.57) -0.933 -1.478 (-0.42) (-0.47) 2.561 2.807 ** (2.53) (1.00) 1.382 *** 0.018 (3.60) (0.05) Mom 2.568 ** (2.46) 1.288 ** (2.74) 2.904 ** (2.55) 0.249 (0.15) 1.826 (1.59) 1.037 (1.47) 0.970 (0.55) 1.736 * (2.02) 0.723 (0.49) 1.906 * (1.98) 1.734 (1.24) 0.545 (0.33) 0.246 (0.11) 1.364 *** (5.86) Winner 2.560 *** (3.33) 0.375 (0.34) 0.872 (0.94) 3.359 ** (2.16) 1.455 * (1.92) 0.407 (0.57) 0.413 (0.71) 2.944 *** (3.38) 1.239 (1.35) 1.269 (1.49) 1.161 (1.16) 0.614 (0.58) 1.537 * (1.92) 1.400 *** (5.14) Mild Loser 1.010 (0.92) -0.644 (-0.51) -0.497 (-0.46) 4.199 ** (2.30) 1.015 (1.16) -0.151 (-0.19) -0.855 (-1.09) 2.595 ** (2.55) 2.253 ** (2.09) -0.329 (-0.29) -0.524 (-0.52) 0.529 (0.45) 0.255 (0.28) 0.681 (1.62) Mom 1.549 (1.57) 1.019 * (1.80) 1.369 *** (2.98) -0.840 (-1.13) 0.440 (0.87) 0.558 (1.41) 1.269 *** (3.06) 0.349 (0.63) -1.013 (-1.25) 1.598 ** (2.47) 1.686 *** (2.93) 0.084 (0.15) 1.281 ** (2.60) 0.719 ** (2.90) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively 24 Pessimistic Winner Loser 3.502 2.880 * (1.64) (1.73) 2.031 2.856 * (1.43) (1.82) 1.622 2.620 (1.25) (1.31) 1.826 ** 2.344 (2.10) (1.38) 2.358 *** 3.384 ** (2.79) (2.24) -0.018 1.228 (-0.02) (1.04) 1.319 * 1.723 (1.85) (1.48) -0.463 -0.881 (-0.49) (-0.54) 1.980 ** 3.823 ** (2.45) (2.41) 0.736 1.861 (0.86) (1.05) 1.601 1.949 (1.54) (1.46) 1.442 1.546 (1.22) (1.00) 2.161 ** 2.734 ** (2.60) (2.30) 1.546 *** 2.159 *** (5.45) (6.61) Mom 0.622 (0.56) -0.825 (-1.33) -0.998 (-0.82) -0.518 (-0.39) -1.026 (-0.79) -1.246 (-1.66) -0.403 (-0.51) 0.418 (0.25) -1.843 (-1.43) -1.125 (-0.85) -0.347 (-0.39) -0.104 (-0.14) -0.574 (-0.67) -0.613 *** (-3.26) Table 5 Momentum Returns Using Alternative Sentiment Classification Country Bangladesh China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Singapore South Korea Taiwan Thailand Local Sentiment Optimistic Pessimistic N/A N/A 0.668 (1.53) 0.343 (0.68) 2.288 (1.68) 1.105 ** (2.06) 1.025 ** (2.61) 1.560 (1.59) N/A -0.761 (-0.73) N/A 1.749 ** (2.53) 2.074 (1.18) 1.174 (1.67) 1.097 (1.60) 0.879 (0.78) 0.786 (0.68) 0.945 (1.19) -1.239 (-1.57) 0.149 (0.16) N/A 0.169 (0.17) N/A 0.316 (0.26) -0.258 (-0.54) -0.471 (-0.49) Global Sentiment Optimistic Pessimistic 2.101 ** 1.296 (2.49) (1.38) 0.257 -0.090 (0.41) (-0.15) 1.446 -0.354 (1.59) (-0.34) 0.107 -0.672 (0.08) (-0.56) 1.515 * -0.312 (1.76) (-0.28) 1.341 ** -1.176 * (2.40) (-1.72) 1.493 -0.294 (1.22) (-0.42) 1.131 0.273 (1.66) (0.20) 0.760 -1.457 (0.71) (-1.30) 1.667 ** -1.081 (2.28) (-0.87) 1.769 * 0.652 (1.73) (0.84) 0.500 -0.140 (0.42) (-0.22) 0.727 -0.362 (0.48) (-0.50) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively 25 Table 6 Momentum Portfolio Returns Using Alternative Sentiment Proxies Country Bangladesh China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Singapore South Korea Taiwan Thailand University of Michigan Sentiment Index Optimistic Mild Pessimistic 4.949 ** 0.910 0.710 (2.52) (1.06) (0.67) 2.153 * 0.772 -0.697 (2.06) (1.55) (-1.16) 1.785 1.620 *** -0.655 (1.45) (3.45) (-0.55) -1.790 -0.492 -0.045 (-0.63) (-0.03) (-1.19) 1.573 * 0.413 -0.665 (1.88) (0.74) (-0.52) 0.402 0.659 -0.977 (0.88) (1.56) (-1.32) 3.401 ** 0.453 -0.069 (2.74) (0.81) (-0.09) 0.514 0.403 1.358 (1.72) (0.89) (0.26) -0.298 -0.945 -1.265 (-0.14) (-1.34) (-0.98) 2.834 *** 1.220 * -0.734 (3.00) (1.90) (-0.57) 1.973 *** -0.223 0.657 (0.41) (3.50) (-0.26) 0.031 0.248 -0.102 (0.02) (0.43) (-0.14) 1.167 ** -0.333 0.228 (0.09) (2.46) (-0.40) Baker and Wurgler (2006) Composite Index Optimistic Mild Pessimistic 1.135 0.283 4.860 *** (1.31) (0.28) (3.64) 0.515 0.630 1.023 (1.13) (1.02) (1.31) 3.118 *** 0.143 0.628 (3.28) (0.19) (0.78) -1.271 -0.464 -0.833 (-0.86) (-0.49) (-0.73) 1.860 ** -0.669 0.647 (2.05) (-0.82) (0.77) 0.278 0.417 -0.500 (0.41) (0.85) (-0.65) 0.869 0.898 0.335 (0.60) (1.58) (0.53) 0.545 0.771 0.111 (0.54) (0.81) (0.12) -0.554 -0.722 -1.997 * (-0.38) (-0.75) (-1.84) 1.741 1.144 -0.910 (1.61) (1.41) (-0.71) 1.355 0.612 2.174 *** (0.98) (1.00) (3.12) -1.897 0.624 0.017 (-1.23) (1.08) (0.03) -0.100 1.063 * 0.120 (-0.06) (1.74) (0.15) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 26 Table 7 Firm Size, Local Investor Sentiment and Momentum Portfolio Returns Country China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Philippines South Korea Taiwan Thailand Large 0.759 (1.38) 1.623 * (1.94) 0.743 (0.64) 1.299 (1.59) 0.850 (1.55) 1.419 (1.20) 2.021 (1.45) 1.983 * (1.73) -0.832 (-0.42) 1.753 (1.53) Optimistic Medium 0.500 (1.20) 1.527 ** (2.21) 0.627 (0.39) 2.214 ** (2.34) 1.020 ** (2.49) 2.839 * (1.98) -0.694 (-0.61) 2.476 *** (2.89) 1.812 (0.74) -0.223 (-0.19) Small 0.321 (0.62) -0.039 (-0.04) 1.567 (1.18) 1.246 (1.45) 1.081 * (1.79) 1.730 (1.43) -1.411 (-0.94) 1.573 (1.43) 1.091 (0.80) 0.207 (0.18) Large 0.833 (1.30) 1.824 *** (3.29) -2.118 (-0.56) 0.144 (0.14) 0.101 (0.23) 0.942 ** (2.08) 0.504 (0.48) 1.199 (1.55) 2.565 * (2.04) 0.978 (1.33) Mild Medium 0.594 (1.24) 1.970 *** (3.75) -2.449 (-0.70) 0.168 (0.20) 0.772 ** (2.22) 1.037 ** (2.27) -0.690 (-0.50) 1.229 ** (2.53) 1.538 * (1.96) 1.463 ** (2.18) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 27 Small 0.111 (0.30) 1.653 *** (2.70) -4.057 (-1.48) -0.667 (-0.73) 0.981 *** (2.73) 0.251 (0.40) 0.469 (0.33) 0.938 * (1.83) 1.557 (1.68) 1.103 * (1.72) Large 0.158 (0.16) -1.514 (-0.97) 0.901 (1.69) 0.130 (0.07) -2.453 ** (-2.07) -0.870 (-0.56) -0.258 (-0.19) -0.353 (-0.17) -1.333 (-1.40) -2.431 (-0.93) Pessimistic Medium 0.089 (0.15) 2.183 (1.34) 3.938 ** (3.59) 1.463 (1.03) -2.351 * (-1.86) -0.184 (-0.14) 2.010 (1.51) -1.906 (-1.15) 0.790 (1.40) 0.160 (0.10) Small -0.828 ** (-2.06) -1.365 (-0.77) 0.199 (0.15) 1.618 (0.99) -2.223 * (-1.80) 0.052 (0.05) -1.922 (-1.49) -1.684 (-0.79) -0.378 (-0.41) -2.477 (-1.55) Table 8 Firm Size, Global Investor Sentiment and Momentum Portfolio Returns Country Bangladesh China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Singapore South Korea Taiwan Thailand Optimistic Large Medium 1.471 1.102 (1.00) (1.32) 2.256 *** 0.977 ** (3.23) (2.37) 3.074 ** 4.335 *** (2.36) (3.39) 1.121 0.108 (0.06) (0.44) 2.046 4.165 ** (0.97) (2.68) 0.656 1.367 * (0.80) (2.05) 0.928 1.750 (0.61) (1.07) 2.608 *** 1.380 (1.04) (2.96) -0.977 1.475 (-0.42) (0.89) 1.225 2.952 ** (1.09) (2.32) 1.009 3.209 (1.37) (0.76) 1.156 0.851 (0.72) (0.46) 0.386 0.102 (0.04) (0.18) Small 0.812 (0.84) -0.449 (-0.75) 2.576 * (2.03) -0.011 (-0.01) -0.002 (0.00) 0.597 (0.75) 0.561 (0.24) 0.611 (0.48) 1.406 (0.65) 2.554 * (2.03) -0.640 (-0.50) -0.028 (-0.01) 1.609 (0.89) Large 1.739 ** (2.42) 0.862 (1.50) 1.468 *** (3.09) 1.188 * (1.75) 0.750 (0.96) 0.211 (0.47) 1.233 *** (2.89) 0.624 (0.70) -0.222 (-0.22) 1.482 *** (2.70) 1.390 ** (2.04) 1.126 * (1.81) 1.964 *** (3.22) Mild Medium 2.210 *** (2.85) 0.765 (1.64) 2.583 *** (5.36) 0.310 (0.40) 0.221 (0.29) 0.559 (1.34) 1.345 *** (3.32) 0.937 * (1.76) -1.397 (-1.30) 2.206 *** (4.14) 1.690 *** (3.41) 0.307 (0.55) 1.349 ** (2.19) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 28 Small -0.539 (-0.51) 0.697 ** (2.03) 0.544 (0.91) -2.263 ** (-2.61) 1.094 (1.50) 1.063 ** (2.57) 0.488 (1.06) -0.890 (-0.98) -0.801 (-0.77) 1.557 * (1.81) 1.348 ** (2.09) 0.175 (0.31) 0.942 (1.51) Large 1.263 (1.10) -0.747 (-0.78) -1.155 (-0.89) 0.339 (0.23) -1.416 (-0.84) -1.525 * (-1.87) -0.759 (-0.74) -0.442 (-0.26) -0.161 (-0.13) -1.073 (-0.66) -0.648 (-0.61) -0.100 (-0.12) -1.128 (-0.98) Pessimistic Medium 0.656 (0.55) -0.481 (-0.83) -0.934 (-0.83) 0.085 (0.06) 0.172 (0.15) -1.092 (-1.42) -0.320 (-0.36) 0.487 (0.26) -2.073 (-1.27) -1.474 (-0.91) -0.157 (-0.18) 0.085 (0.10) 0.478 (0.58) Small -0.492 (-0.27) -1.328 *** (-3.16) -0.628 (-0.44) -1.605 (-1.34) -1.167 (-0.85) -1.039 (-1.25) -0.087 (-0.13) 1.251 (0.65) -2.788 ** (-2.32) -1.116 (-1.08) 0.354 (0.39) 0.017 (0.02) -1.044 (-1.11) Table 9 Trading Volume, Local Investor Sentiment and Momentum Portfolio Returns Country China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Philippines South Korea Taiwan Thailand High Vol. 0.853* (1.74) 1.078 (1.48) -0.495 (-0.16) 1.207 (1.32) 1.773*** (2.77) 0.982 (0.99) 0.332 (0.15) 2.201* (2.03) -0.888 (-0.33) 0.138 (0.11) Optimistic Med. Vol. 0.278 (0.52) -0.069 (-0.11) 1.630 (0.66) 2.741** (2.70) 1.086** (2.33) 1.715 (1.50) -0.851 (-0.61) 2.640*** (2.97) 0.751 (0.47) 1.066 (0.87) Low Vol. 0.359 (0.60) -0.493 (-0.57) -1.458 (-0.95) 1.171* (1.77) 0.855** (2.37) 2.060* (2.09) -0.114 (-0.07) 3.318*** (3.90) 3.391** (3.16) -0.669 (-0.63) High Vol. 0.728 (1.11) 1.289** (2.24) -1.491 (-0.33) -1.054 (-1.11) 0.394 (0.98) 1.314** (2.62) -0.384 (-0.30) 1.140** (2.06) 2.787* (2.18) 0.940 (1.27) Mild Med. Vol. 0.874 (1.43) 1.982*** (3.94) -1.391 (-0.58) 0.511 (0.57) 0.764** (2.38) 1.012** (2.08) 0.557 (0.46) 1.351** (2.29) 2.776** (2.38) 0.854 (1.17) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 29 Low Vol. 0.435 (0.74) 2.228*** (3.73) -1.343 (-1.51) -0.340 (-0.42) 0.906*** (3.13) 0.966* (1.83) -0.547 (-0.41) 1.329** (2.05) 1.335 (1.34) 1.760** (2.12) High Vol. -0.018 (-0.04) -0.251 (-0.15) 0.373 (0.18) 1.880 (1.38) -2.112 (-1.69) -1.483 (-1.00) 0.272 (0.24) -0.561 (-0.37) 0.570*** (5.64) -2.179 (-1.22) Pessimistic Med. Vol. -0.507 (-0.85) 0.669 (0.41) -4.018 (-0.72) 1.373 (0.95) -3.032** (-2.56) -0.483 (-0.38) 0.452 (0.44) -0.680 (-0.34) 0.805 (0.80) -1.905 (-0.98) Low Vol. 0.140 (0.16) -0.747 (-0.59) -7.297 (-1.42) 0.171 (0.13) -2.049* (-1.87) 0.727 (0.84) -0.535 (-0.38) -2.221 (-1.22) -0.414 (-0.39) -1.190 (-0.58) Table 10 Trading Volume, Global Investor Sentiment and Momentum Portfolio Returns Country Bangladesh China Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Malaysia Pakistan Philippines Singapore South Korea Taiwan Thailand High Vol. 1.930 (1.61) 0.568 (0.81) 1.232 (0.83) -0.240 (-0.08) 1.885 (1.10) 0.946 (0.98) 0.428 (0.29) 0.521 (0.43) 1.691 (1.04) 1.520 (1.41) 1.059 (0.77) 0.141 (0.08) 0.059 (0.03) Optimistic Med. Vol. 3.038 *** (3.04) 1.292 ** (2.13) 2.917 ** (2.38) 0.937 (0.54) 3.546 * (2.00) 1.274 * (1.84) 0.984 (0.60) 2.637 * (1.80) -0.756 (-0.50) 3.048 ** (2.66) 2.120 (1.32) -0.233 (-0.13) -0.461 (-0.19) Low Vol. 1.068 (0.85) 1.377 * (2.07) 3.141 ** (2.37) -0.101 (-0.13) 2.161 (1.34) 0.874 (1.65) 0.787 (0.45) 1.295 (0.82) 1.466 (0.54) 2.449 ** (2.42) 1.685 (0.85) 1.076 (0.49) 1.855 (0.68) High Vol. 2.718 *** (3.14) 1.122 * (1.76) 1.774 *** (4.10) 0.865 (0.95) 0.242 (0.30) 0.881 ** (2.04) 1.596 *** (3.25) 1.064 (1.39) -2.010 (-1.56) 2.369 *** (3.89) 1.495 ** (2.48) 0.539 (0.91) 1.111 (1.61) Mild Med. Vol. 1.411 (1.62) 0.918 (1.52) 1.542 *** (3.00) -0.419 (-0.59) 0.937 (1.33) 0.440 (1.06) 1.113 ** (2.60) 0.816 (1.09) -0.911 (-0.95) 1.441 * (1.90) 2.009 *** (3.25) 0.006 (0.01) 1.659 *** (2.64) *, **,*** represent statistical significance at 10, 5, and 1 percent level respectively. 30 Low Vol. -0.366 (-0.32) 0.612 (1.11) 0.552 (0.99) -2.128 ** (-2.52) 0.092 (0.14) 0.620 (1.60) 1.447 *** (3.07) -1.149 * (-1.72) -1.290 (-1.37) 0.893 (1.15) 1.610 ** (2.59) -0.077 (-0.12) 1.324 ** (2.05) High Vol. 1.186 (0.84) -0.483 (-1.00) -1.065 (-0.80) 0.540 (0.39) -1.256 (-0.91) -1.358 (-1.64) -0.775 (-0.75) 2.324 (1.46) -0.995 (-0.56) -0.557 (-0.42) 0.398 (0.46) 0.295 (0.33) -0.725 (-0.79) Pessimistic Med. Vol. 0.486 (0.48) -1.079 * (-1.97) -0.540 (-0.48) 0.382 (0.36) 0.144 (0.10) -1.219 (-1.68) -0.011 (-0.01) 1.063 (0.72) -1.196 (-0.89) -0.806 (-0.76) -0.528 (-0.60) 0.693 (0.93) -0.820 (-0.92) Low Vol. -1.107 (-0.89) -0.813 (-0.95) 0.240 (0.22) -1.405 (-1.25) -1.215 (-1.08) -0.577 (-0.91) 0.306 (0.59) 0.055 (0.03) -1.929 (-1.30) -0.399 (-0.33) 0.217 (0.25) -0.111 (-0.13) -0.585 (-0.63)