* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download View DOC File - Plant Accession at Lake Wilderness Arboretum

Survey

Document related concepts

Human impact on the nitrogen cycle wikipedia , lookup

Arbuscular mycorrhiza wikipedia , lookup

Entomopathogenic nematode wikipedia , lookup

Plant nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Surface runoff wikipedia , lookup

Soil erosion wikipedia , lookup

Soil horizon wikipedia , lookup

Soil respiration wikipedia , lookup

Terra preta wikipedia , lookup

Crop rotation wikipedia , lookup

Canadian system of soil classification wikipedia , lookup

Soil salinity control wikipedia , lookup

Soil compaction (agriculture) wikipedia , lookup

No-till farming wikipedia , lookup

Soil food web wikipedia , lookup

Soil microbiology wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

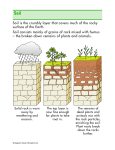

Down and Dirty - The Arboretum’s Soil John Neorr About 15,000 years ago, if you were standing in the Arboretum, you would be very cold. That’s because you would be standing on the Vashon glacier. 3,000 feet thick, this glacier fully occupied the trough between the Olympic and Cascade Mountains and extended as far south as Olympia. 4,000 years later, after this glacier retreated to Canada where it belonged, it left behind the topology and parent soil material that you see today in the Arboretum (and your backyard). Why is this important? Perhaps it is not, but learning about the geologic history of Puget Sound can be a fun way to learn about soil and what might or might not grow in it. This article describes the different types of soil that are found in the Arboretum and also itemizes some of the native plants found in that soil. Layering of Soil The composition of soil is generally categorized into 4 layers. The top layer (O) is a thin layer of organic material that is relatively undecomposed. In the forest, we call this duff. Below this layer we have the “A” layer – commonly called topsoil. Topsoil is a layer of decomposed organic material and a (typically) aerobic mix of sand, silt, and clay and is where the roots of herbaceous plants grow. Below the topsoil layer is the subsoil (B) layer consisting of higher concentrations of clay and other minerals with some organic material. Roots of some plants, especially trees, can penetrate this layer of soil. The “C” layer of soil is the parent material from which upper layers are Soil Layers derived. In the case of the arboretum, this parent material is mostly glacial till (rocks deposited by a glacier) or glacial outwash (gravels, sand, and silt deposited by glacier melt water). The upper layers of soil seen today in undisturbed areas of the Arboretum are the result of glacial materials weathering over thousands of years. Depending on climate and other environmental conditions, it can take 1000 year to create a measly 2-4 cm of topsoil. Arboretum Soil Types The type and location of soils in the Arboretum was obtained from the US Department of Agriculture Web Soil Survey (WSS) site: http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/. This site is available to the public and, although somewhat painful to operate, can be used to determine what kind of soil you have on your property (if you are not living on fill dirt). The most predominate soil in the Arboretum is Everett (Ev). This is a fancy term for “rocky” although some Everett soils have less rock than others. This soil originates from glacial outwash which, as defined by the Arctic Geobotanical Atlas (AGA), is “gravel, sand, and silt, commonly stratified, deposited by melt water as it flows from glacial ice.” Everett soil can also have some volcanic ash in its upper portion. At least 90% of the soil in the Arboretum is Everett. Most is EvC which means that the land is minimally sloped. The Arboretum forest has some EvD soil which means that the land is sloped 15%-30%. Typical Everett soil has an A layer thickness of 2 inches, B layer of 17 inches and a C layer of 30 inches. The two remaining types of soil found in the Arboretum are Norma (No) and Alderwood (AgD). The Norma soil is found in the southern end of the Smith Mossman Azalea garden. Norma soil consists of deep, poorly drained soil formed in old alluvium (sediment) from glacial depressions. This seems to imply that sometime in the distant past, Arboretum map showing soil types Lake Wilderness was larger than it is today. The remaining soil type, Alderwood, is found in the southeast corner of the Arboretum forest. Alderwood soil is a bit less acidic (pH 6.2 versus pH 5.6) than Everett soil and is less rocky. My personal experience would suggest that Alderwood is more likely to have a layer of hardpan than is Everett. What grows where? Everett and Alderwood soils tend to support the same species of native plants. Although we do not have too much Alderwood soil, we find Douglas-fir, western hemlock, salal, Oregon-grape, red huckleberry, and sword fern growing in both soils in the Arboretum. Because Alderwood soil is somewhat loamier than Everett, it is more commonly used for farmland and orchards. This bodes well for our miniature Garry oak woodland recently planted in the Alderwood soil area. Some documentation also indicates that Alderwood soil supports Pacific rhododendron, evergreen huckleberry, and Orange huckleberry better than Everett soil. Conversely, the documentation states that ocean spray and trailing blackberry prefer the Everett soil type. Not surprisingly, Norma soil is preferred by wetland plants including thimbleberry, salmonberry, willow, skunkcabbage, sedges, and rushes. In the natural areas of the Arboretum, over time Mother Nature has taken care of “right plant, right place.” However for new plantings in the Arboretum, knowing soil type will help guide our planting decisions. Likewise, you may want to consider your soil type when thinking about planting native species in your backyard.