* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download File Name:

Extrachromosomal DNA wikipedia , lookup

Genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

Molecular cloning wikipedia , lookup

Cre-Lox recombination wikipedia , lookup

Gene therapy of the human retina wikipedia , lookup

Site-specific recombinase technology wikipedia , lookup

Polycomb Group Proteins and Cancer wikipedia , lookup

Therapeutic gene modulation wikipedia , lookup

Mir-92 microRNA precursor family wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

No-SCAR (Scarless Cas9 Assisted Recombineering) Genome Editing wikipedia , lookup

DNA vaccination wikipedia , lookup

Artificial gene synthesis wikipedia , lookup

History of genetic engineering wikipedia , lookup

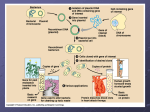

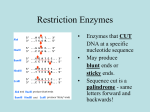

Biotech 201: The Technology That Drive Biotech Dr. Collins Jones: Welcome back, welcome to Biotech 201: The Technology That Drives Biotech. This is Collins Jones again and I once again will be your presenter. Objectives So in this webinar, what we’d like to be able to talk to you about is recombinant DNA. We want you to be able to find recombinant DNA. By the end of this webinar we want you to understand how we make a recombinant DNA molecule and of course once we make the molecule we want to know what you can do with it. And so we’ll explain some different uses with a focus on how to make what’s called a recombinant protein, which of course comes from recombinant DNA. And then once we make those proteins, how is it used and we pretty much going to do this in a context of a therapeutic protein. Remember that cells are what Biotech is all about and cells are going to be our factories, if you will, to produce the protein. And so there are different kinds of cells, bacteria cells, plant cells, animal cells. So we’re going to help you to understand why in some cases we can use the bacterial cell to make a protein, but in other cases we must use a mammalian cell. We are making this recombinant DNA outside of the cell, so we need to put it back in a cell and that’s called transferring our DNA and our different methods to do that. And so once again we want to cover those methods and how and why you would use one method over another. We can’t use just one cell to make our protein. We have to have lots of cells. And if we’re going to make a protein using lots of cells this is really a bio-manufacturing process. So we just like to outline the basic steps in bio-manufacturing and specifically the manufacture of a therapeutic protein biologically is often referred to as a campaign. And then since cells are so important they are really central to our production of a product, we need to be able to protect them and make sure they’re always available to us. And to that end we create what’s known as a cell bank. So we’ll discuss a little bit about cell banking. And from cell banking we’re going to go from one vial of cells into 20,000 litres of cells that’s essentially scale-up, so we’ll talk a little bit about that. And then this is a protein and proteins are much different than traditional chemicals, small molecules. So there are some slightly different aspects to the purification of a biologic product as opposed to a chemical or traditional pharmaceutical product. So hopefully we’ll be able to convey to you those differences. Cells So let’s get started. Just to sort of refocus you and bring everything back in line, remember that Biotech is all about cells. Cells are what we study in terms of diseases, but cells also are what BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 1 we use to make our Biotech products. And so in this unit, unlike the previous unit, we’re going to deal with how to use a cell to make a protein product. So instead of looking at a cell and saying, what went wrong with it to cause a disease? Now we’re going to take up a cell and use that cell to make our protein product, so our cell is our factory. But let’s just review a little bit about what cells do specifically in the context of how a cell makes a protein. Cells Manufacture So first thing we have to do is we have to feed our cells and allow them to manufacture the protein. So what we have over here, this is a carbohydrate molecule, which is a fancy term for sugar and sugars provide energy. So we feed the cells sugars and there’s lots of other things that cells need to be fed, this includes lipids, things like cholesterol and fatty acids, we feed them glucose, which is our carbohydrate, and we feed them amino acids, because if you remember from our 101 webinar, amino acids are the building blocks for proteins. And so cells bring all of this in and through a process called metabolism they create energy and synthesize molecules. And cells are the only thing that can do this for proteins. So cells are our factories. And ultimately remember that proteins are made on the ribosome and they can either be retained in the cell. They can be inserted in the cell membrane or ideally they could be secreted. And remember a secreted protein is a protein that is released from the cell to the outside of the cell and the context of a therapeutic protein or manufacturer protein. We love secreted proteins because they’re much easier to purify. We can just remove the cells and then all we have to deal with is the proteins that are out in the mixture away from the cell. Now, one thing I want to mention at this point is remember that we need to grow these cells, we need to feed the cells. The food for cells is called nutrient media or cell media. So this is just a specialized formulation of ingredients that has the amino acids, the lipids, the glucose in it to specifically formulate it to feed cells. And so we have to purchase that and we’ll talk a little bit about that when we talk about different cells, because different cell types require different types of media, all right. Genetic Flow Also, just to remind you how we actually make a protein inside the cell. So remember the information to make a protein is contained in a specific sequence or unit of DNA called the genes. Remember a gene is a specific sequence nucleotides that contains the information to make a protein. This gene, this specific sequence of DNA is copied or transcribed into messenger RNA. So the messenger RNAs is just a copy of the gene, it’s a mobile copy of the gene, if you will. And the messenger RNA is made in the nucleus of the cell and is then transported to the ribosome, where the sequence of RNA is read or translated to make a protein BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 2 and the ribosome reads the information on the RNA to connect one amino acid to another in order to finally assemble our final protein product. And then remember the final protein product must have a specific 3 dimensional shape in order to be functional, and that’s what the ribosome does. So the amino acids are connected one to another. As they come out of the ribosome, as that sequence of amino acids comes out of the ribosome, that amino acid sequence, our polypeptide is then folded into a unique 3 dimensional shape that then allows the protein to carry out its function. And remember our classes of proteins include antibodies receptors and enzymes. Restriction Enzymes So how do we go about this? Because really what we’re going to discuss in this section is this concept of recombinant DNA. And again, if you just take a minute and think about the word recombinant DNA is recombined DNA. So really what our focus is here is we’re going to move a gene, a specific sequence of DNA, we’re going to move a gene from one organism to another. So in other words, we’re going to take a human gene, maybe the gene that contains the information to make insulin, take that piece of DNA, that insulin gene and move it from a human cell into a bacteria cell. And if you recall from our 101 webinar, DNA is just a chemical. So the human insulin gene, which is made up of nucleotides, just chemicals, that human insulin gene can be put into an E. coli cell, a bacteria cell, and chemically it looks just like E. coli DNA. So now the E. coli can read that sequence of DNA and the E. coli can make human insulin just by reading the sequence. But the challenge with this is, if you will remember human beings, each human cell has lots and lots of DNAs, 3 billion letters. Only a very tiny fraction of those letters make up any particular gene. So I can only work with a little bit of DNA at a time. I don’t want to work with all 3 billion letters. So the first step towards making a recombinant DNA, towards combining my human DNA with E. coli DNA is to cut it into small manageable size pieces. And the tool that we use to do this is an enzyme called a restriction enzyme. Restriction enzymes are proteins or enzymes made by bacteria and bacteria made these specifically to chop up any foreign DNA that is virus DNA that gets inside the bacteria. It’s kind of the way a bacteria cell protects itself. And scientists recognize that this happened and said geez, maybe we could use this restriction enzyme for our own purposes, namely to cut DNA up into manageable size pieces. And that in fact is what a restriction enzyme does. There are a hundreds of different restriction enzymes and each restriction enzyme cuts DNA at a different place. So below here we’ve illustrated a couple of the more commonly used restriction BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 3 enzymes EcoR1, Sma1, and Not1, each of these restriction enzymes comes from a different bacterial cell. So I’m just going to go through the first one, EcoR1 comes from E. coli, strain R and the number 1 is the first restriction enzyme that was purified from E. coli. Now what makes these so very useful is not only as a restriction enzyme able to cut DNA, but is able to cut the DNA at a very specific sequence. And EcoR1 always recognizes the sequence GAATTC. So any place on a piece of DNA that GAATTC occurs, EcoR1 cuts it. And you notice, by the way, that on the bottom we have the same sequence in reverse. So these are opposite, the same sequence going in opposite directions. And this is called a palindromic sequence, just like Radar is a palindromic word. We have palindromic DNA sequences, and that is what the restriction enzymes recognize. So every time no matter what the DNA is, whether it’s a human piece of DNA, a plant piece of DNA or a bacteria piece of DNA, every time the restriction enzyme EcoR1 sees this piece of DNA, it makes this cut. So to think about doing this in the lab, experimentally what this means is, is you isolate DNA from a human being cell. You can buy this EcoR1. It’s sold by a number of different supply side Biotech companies. You add this EcoR1 enzyme into your test tube with the DNA that you’ve isolated, the EcoR1 then scans the DNA sequence and every time it sees this GAATTC it makes a cut. Similarly SMA1 recognizes CCCGGG and notice again it’s a palindrome and recognizes a so much longer sequence GCGGCCGC. And so this gives us the ability to cut DNA at different sequences, that’s really all this is about, but I get reproducible cuts, I know exactly what’s being cut and I’m taking this big long piece of DNA and now cutting it up into very small bite size pieces, if you will, that are easy to work with. So that’s our value in a restriction enzyme. That’s our first step towards making a recombinant DNA. Recombinant DNA Now though we have to actually make the recombinant molecule, that is we have to combine two different pieces of DNA. So what we’re now going to do is take bacterial DNA and human DNA and cut both of them with the same restriction enzyme. Because remember, if I use EcoR1 whether it’s bacterial DNA or human DNA, we’re going to cut exactly the same sequence. And if you remember from our 101 webinar, DNA undergoes complimentary base pairing. So Gs match with Cs and As match with Ts. So if I take a piece of DNA from bacteria that’s been cut with EcoR1, I’m going to have this sequence. And if I take the corresponding cut from a human being and add it in, guess what? These guys are going to spontaneously match up to each other and recombine. And that is exactly what we do. So we cut both DNA sources, bacteria and human, with EcoR1 for example, we mix them together on the test tube and they spontaneously by complimentary base pairing, they spontaneously connect to one another and this is what we call our recombinant DNA, because we BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 4 have now combined human DNA with bacterial DNA. And we need to add in another enzyme called the DNA ligase and the DNA ligase basically seals the deal. It makes these connections permanent. And if you’re worried about, as some people sometimes do, what happened to the EcoR1, well before we added the DNA ligase we killed the EcoR1 so it no longer works. So let’s just introduce a few vocabulary terms here that are relevant to our recombinant DNA process. First, we have ligation we’re ligating or joining two different pieces of DNA together, so that’s what the ligase does. It chemically bonds or chemically connects permanently these two pieces of DNA. A vector is a specific piece of DNA that has been designed to allow us to transport, if you will, or to move DNA from one cell to another cell, so in other words this is how I get my human gene out of a human cell and into a bacteria cell or hamster cell or tobacco cell or whatever cell I want to use to make my protein with. The most common type of vector by far is called the plasmid. And we’ll have a picture of a plasmid on the next page, but it is simply a circular piece of DNA that occurred naturally in bacteria and scientists have since then engineered or designed their own plasmids to do what they need to do. Each vector, in our case plasmid, is chosen for a specific characteristics, one is, how big is the gene? So, different plasmids can accommodate different size genes or different pieces of DNA. And the other issue is, is how do I know when I’ve added my recombinant DNA back into a cell, how do I know that my human insulin gene is now inside of the E. coli cell? And so I need a marker. I need some way to detect the fact that the cell is actually taken up this extra recombinant DNA and then it’s now present. And so, we called this the selection marker and usually this is antibiotic resistance or we can actually add in markers that cause the cells to change color. We’re going to focus on antibiotic resistance for reasons that I hope will be clear to you in a slide or two. So again, our whole idea here is that we’re moving DNA or genes from one organism to another. Why? Because I can’t use human beings as a source of insulin, I can’t take a human being, put them in a little chair, connect nutrient media to them and then have their pancreas crank out insulin and harvest it from them. I need another way to produce lots and lots of insulin. So I’m going to do that in cells, but not every cell makes insulin. So what I need to do is take the information to make insulin, that is the insulin gene, put it into that cell and now the cell, whatever cell I choose becomes an insulin factory for me. Making a Plasmid So let’s talk about how we make a recombinant plasmid. Because remember the plasmid is really the piece of DNA that we’re going to use to move our gene around with. So here on the right hand side I have my human DNA and within that DNA I have my gene of interest. I now have my plasmid, which you can purchase commercially. There’s number of companies that sell plasmids and different plasmids have been designed for different purposes. This is in one test BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 5 tube, this is in a different test tube. To both test tubes I add my restriction enzyme, it could be EcoR1. EcoR1 cuts the plasmid open, because I’ve designed the plasmid to have a sequence of DNA, the As, Gs, Ts, and Cs that my restriction enzymes will recognize. And then similarly, the human DNA is cut by the same restriction enzymes. So now I have my gene that I’m interested in, my human piece of DNA and I have my plasmid that’s now been cut open. Now I add the contents of the two tubes together and by the complimentary base pairing that we’ve talked about, As to Ts, Gs to Cs, my human DNA floats over, matches up with the plasmid DNA. This takes a couple of hours to do typically in the lab. And then I add my add enzyme DNA ligase in there and the DNA ligase then seals the deal, if you will, make sure that our human DNA is now permanently embedded into the plasmid DNA. And this is now what’s called a recombinant plasmid. What I haven’t talked about yet is what we call antibiotic resistance gene. This comes with the plasmid and this occurred in nature. So what we mean by antibiotic resistance is this gene codes for a protein that allows a bacteria cell to destroy any antibiotics that may kill it or a specific antibiotic that will kill it. So any bacteria cell that has this antibiotic resistance gene in it will be able to survive a particular antibiotic, and this is how we’re going to do our selection. Making Recombinant Proteins in Bacteria So the next step, I’ve made my recombinant plasmid, the next step is, this is all still in the test tube, it’s not in the cell. So the next thing I need to do is put my plasmid inside the bacteria cell. And on the next slide we’ll describe the methodology for doing that, but for right now if you could just trust me and say we can in fact put this plasmid inside the bacteria cell. You now notice that I have my human DNA, my insulin gene here, but I also have my antibiotic resistance gene on the same plasmid. So now this bacteria, because it has the plasmid in it, it has the information to make an enzyme that will destroy an antibiotic. So now what happens is I take my bacteria cell and I put it into a flask and begin to grow it. And what you notice here is that some bacteria don’t have the plasmid others do, because the process of transferring the plasmid into the bacteria cell isn’t 100% effective. So, not every bacteria cell gets a plasmid. So what I don’t want to pay to do is feed bacteria cells that don’t have my plasmid, because they’re not going to make my insulin. So what I do is I take my bacteria cells, I put them in a flask, I allow it to grow for a little bit and BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 6 then I add an antibiotic. And now, after a day or two only the bacteria cells that have the plasmid in it are able to make the enzyme that destroys the antibiotic. And so, within 2 or 3 days, the only cells growing in my flask in the presence of antibiotic are the bacteria cells that have the plasmid. So now I’m happy because all of these cells if they have the plasmid because they’ve survived, they also have the gene to make insulin. So now I let these cells make their protein. The bacteria now begin to produce insulin for me and I can now harvest and purify this insulin, which is what we talk about at the end of this. Making Recombinant Proteins In Mammalian Cells So we can do this process not only in a bacterial cell, but essentially the same methodology is used to make a protein in a mammalian cell. So a mammalian cell is just an animal cell, specifically what’s typically used in the Biotech industry are what are called CHO cells, which stands for Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. We also sometimes use to produce antibodies something called NS0 cells and these are actually cells derived from a mouse. So why do we use these cells? Are these absolutely the best cells to use? Not necessarily, but those are the types of cells that have been approved by the FDA and it’s much cheaper to go with what the FDA agrees with than to go and spend 5 to 10 years getting a whole new cell line approved, although a number of companies are now working on that just because of the production advantages. So the concept out here is exactly the same. We take a human gene, we cut it out using a restriction enzyme, we insert it into a plasmid and we put the plasmid into our producer cell, in this case a CHO cell. And here instead of insulin we’re using a protein called Erythropoietin which is abbreviated as EPO. EPO is a protein that stimulates red blood cells to grow, so we use EPO if we’re deficient in red blood cells. If I give patients EPO they begin to make lots of more red blood cells. And the same process occurs, the CHO cells then read the information and the EPO gene they synthesize the EPO protein, which we then can use as a therapeutic. Transfer of DNA But at this point, you’re probably wondering why would we use a Chinese Hamster Ovary cells as opposed to an E. coli cell? And we’re going to address that in just a second, but let’s talk a little bit about how we transfer the DNA into a particular cell. And the methods work in both cells that we’re going to discuss here, whether it’s a bacteria cell or a mammalian cell, but it’s better to use some methods in some cases than others. So let’s go through our 4 methods. The first and oldest method is chemical in nature. And basically what we do here is we heat up and cool down our cells in the presence of calcium chloride, that’s the same stuff that they spread on the road for ice and snow. And basically by BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 7 heating and cooling cells in the presence of calcium chloride, little holes appear in their membrane and then those round circular plasmids that we have in the test tube with them slip in between the holes. And as soon as we stop heating and cooling the cells, then that membrane spontaneously reseals and the plasmid gets trapped inside. And that works okay, it’s not very efficient, maybe 20% of the cells if that many take up the plasmid, but we just need some cells to take it up, because remember we’re going to select over time for only those cells that have plasmid by using the antibiotic resistance. This is really easy to do with bacteria cells. Bacteria cells are pretty strong. They can take heating and cooling and they can take high salt concentrations, but CHO cells aren’t so happy. You can get this to work with CHO cells, but the efficiency is much less and it takes a lot of time. So plan B which can be used for bacteria cells or mammalian cells and it works well for both is a method called electroporation and you see a little bolt of lightning. And essentially what you do is you put the cells in a container that has two electrodes in it, two plates of metal and you send a lot of electricity like 2000 volts between across those two electrodes, those two plates of metal. And as that voltage transmits across the two electrodes, the cells are in the middle, so it’s kind of like hitting the cells with lightning. And again, that punches holes in the cell membrane. And if the plasmid is in there at the same time, the plasmids slips in between those holes called holes caused by the electricity. And we only do this for like a second or two and then the membrane again spontaneously reseals itself, repairs itself, trapping the plasmids inside. The advantage of this method is that it’s very quick. You can do this with a large number of cells in a very short time. In fact in my lab I have one that will do 24 different electroporation at the same time. And so it’s easy, quick and easy way to get things done. But of course if you think about this, it’s basically like striking the cells with lightning, so sadly not all of them survive. But again, because we’re going to grow them anyway and let them divide, they don’t all need to survive, just enough in order to grow them up and then select for our plasmid. The newer, kinder, gentler method is using something called a liposome. And so the lipo comes from lipid, and if you remember from our 101 class, lipid is what a cell membrane is made of. So cell membranes are made of lipids and a liposome is just a lipid body. So basically we’re making an artificial membrane here, but inside of that membrane we’re going to trap our plasmid. So all you do is you make your liposome with the plasmid DNA in it, dump that into your flask, shake it around for a couple of hours. As the liposomes bump into the cells, the cells just absorb the liposome into their membrane and the DNA that’s on the plasmid gets carried into the cell. So nice, kind, gentle method, but it’s very expensive to do. It’s about 2 or $300 for a vial of liposomes and that does two flasks of cells. The last method is called microinjection and this is very, very time consuming and you are literally putting your plasmid DNA into a very specialized syringe and you’re then going to stick BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 8 that syringe into the cell and you do this under the microscope and you can actually direct this right into the nucleus if you want and you can inject your DNA directly into the nucleus of the cell, but this takes about 40 to 60 minutes to do per cell. So this is not a high throughput method, this is normally just used or saved for when we are going to make animals that have recombinant DNA in them. So this would be for example if we want to make a recombinant mouse, not grow cells in culture but actually make the complete animal. We take a mouse egg out of the ovary and inject the DNA into that egg and then fertilize the egg and then re-implant it back into the mouse. Production Options: Mammalian vs. Bacterial Cells Now let’s look at why would we use a bacteria cell versus a mammalian cell? If we look at some of the property of bacteria cells, bacteria cells are very, very simple. They’re not nearly as complex as a mammalian cell. All bacteria cells have are a piece of DNA, called a chromosome, a single piece of DNA, and they have ribosomes. So basically they’re almost like protein factories. Bacteria cells grow very quickly. They divide every 20 to 30 minutes, so I can make lots and lots of cells in a very short time and get a very high yield of proteins. Their growth media is relatively cheap. In my lab it’s about $10 for 1 litre of bacteria growth media or growth food. Bacteria are fairly hardy, so I do need to control my process, but I don’t need to control it at least in terms of growth as tightly as I do for mammalian cells. But the restriction here, the drawback to using bacteria is they can only produce what are called simple proteins. So insulin is a simple protein. It’s just a string of amino acids one connected to another, folded into a particular shape, and bacteria are very, very good at that. However, for a more complex protein, an EPO is an example of a more complex protein, bacteria can’t produce EPO. They can connect the amino acids together, but they can’t do all the other things to the EPO that need to be done in order to make it therapeutically effective. So we select our cell type based on the complexity of the protein that we’re trying to manufacture. So EPO though can be made as you saw on the preceding slides in CHO cells, Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. But CHO cells divide about every 20 hours. So instead of a few weeks to get up to enough cells to produce lots of products, a production campaign can take a couple of months before we have enough cells in order to produce enough protein product to meet our market needs. So one challenge with this is, if you think about this, if I’m growing my CHO cells over a 6 to 12 week period and it takes 20 hours to divide, if somebody accidentally contaminates this culture, for example we get some E. coli in there somehow and the E. coli divides every 20 to 30 minutes, you can imagine that in a very short time the E. coli will take over the culture and we have to start all over again from scratch. The media for a CHO cell is fairly expensive. When I grow CHO cells in my lab it’s about $60 a litre. So remember for bacteria cells that was $10 a litre and now I’m paying $60 a litre and you might be thinking, BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 9 well, $60 isn’t really so bad. But think about the fact that you’re growing these cells in 20,000 litres of media. So we have $60 times 20,000 litres and we need to change this media out about every 3 to 4 days over a 6 to 12 week period. So that adds up to some money. And then if we have our contamination event where we’ve lost all that and we’ve got to start all over again. So it’s really important to control your environment with mammalian cells. And mammalian cells are very sensitive to other types of environmental changes like the growth temperature, how much oxygen is dissolved, how fast you stir the cells to keep them suspended, lots of time and effort is put in to design the bioreactors and things we grow these cells in so that the conditions are just right for this to be optimized for the cells to grow and produce the protein. But the advantage of the mammalian cells is they can produce these complex proteins like EPO. They make sure that EPO is folded correctly and mammalian cells can do something called a posttranslational modification, which is cleverly abbreviated as a PTM and that’s something that bacteria cells can’t do. For manufacturing the most critical post-translational modification is called glycosylation and that’s just a fancy way to say, we need to add sugars to the protein. And the EPO must have sugars added to it after it’s made in order for it to function correctly. Only CHO cells, only NS0 cells, other mammalian cells can do that, bacteria cells cannot do that. So our choice of cells is dictated not just by the cost of growing them, but also by the complexity of the protein that we need to produce. So if it’s a simple protein like insulin we use the bacteria cells such as E. coli, if it’s a complex protein like EPO or an antibody we need to go to something like a CHO cell or an NS0 cell. Recombinant Proteins in Healthcare And there are a number of proteins that are used therapeutically that are on the market right now and these are recombinant proteins. And why again do we call these recombinant proteins? Because they’re made from recombinant DNA, so the idea here is, again if I want to take EPO and make EPO as a therapeutic protein, I identify and isolate the EPO gene, insert that EPO gene into a plasmid and now we have a recombinant plasmid. I take that recombinant plasmid, put it into the CHO cell, the CHO cell reads the information on the EPO gene and makes the protein EPO. But because the EPO was made using recombinant DNA information, it’s now called a recombinant protein, but it’s identical to natural or normal human EPO in every single way. You really can’t tell the difference between one and the other. We’re just assigning it the name recombinant because it was made in a recombinant, using a recombinant DNA process. And so examples to these proteins included our EPOs, our antibodies and a number of vaccines are made using this technology too. So this is a growing field and lots of lots of business and market opportunities for this. BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 10 Engineered Mammalian Cell Uses Now one thing that we do want to mention is the idea that if I’ve taken all this time to isolate the gene, to insert it into a CHO cell, you know I made this sound fairly simple, but this could be anywhere from 1 to 10 year literally 10 year process. So what I need to do now is once I’ve made these engineered cell lines, these recombinant cell lines, I want to make sure that nothing happens to them. So once I make my cell line, once I put my recombinant protein in there, I take a portion of these cells and I freeze them down. I cryogenically preserve them. So these are frozen or stored away, and that way if anything happens to the cells that I’m working with, I can go to the freezer and pull out another vial, instead of having to start from scratch. And so these engineered cell lines, again, have lots of applications. One is our protein expression that as they make proteins, and yes protein expressions is really what we’re using to manufacture our therapeutic proteins. So if I’m using a cell line to produce a therapeutic protein, we’re actually doing protein expression. In other cases, I may want to use this as a research model. Here I’m not trying to produce a product, I’m just trying to understand a cellular process. So if you remember from our 101 webinar, we talked about the BRCA gene. If I want to know if BRCA causes cancer I may grow breast cells in culture and then place recombinant BRCA, the recombinant BRCA gene into those breast cells and see if they begin to behave as a cancerous cell. So this is a very quick easy way to start to get some information about the importance of different genes in various cellular processes including cancer. And I can also use cells as an initial screening for drug testing, for drug discovery. So if I’ve created a cancer cell line, I can now check and see what I think is going to be my cancer therapeutic, does it kill these cells? In other cases, do I think this particular product might damage the liver then I can grow liver cells in culture, add the protein to it or the drug to it and see what happens to the liver cells. And the advantage of this over animals initially is that it’s much cheaper, it’s much faster, because I don’t need to make as much product and I can get my answer a lot faster and of course time is money. Ultimately you’re still going to have to end up doing this in animals, but as an initial first screening test so cultures are great way to go. Biologics Production Overview Now, let’s go back here then and really sort of outline the process by which we make a therapeutic protein, by which we’re going to make insulin, by which we’re going to make EPO. So we’re going to start off with the idea that we need to create our recombinant DNA. So we’re growing our cells, we have all of our raw materials and now we’re doing just as we described previously with our restriction enzyme we’re going to cut out the gene that contains information BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 11 to make the protein that we’re interested in. We’re going to also simultaneously with the same restriction enzyme cut open the plasmid, this is exactly what we’ve described on the preceding slides, mix the two together to make our recombinant plasmid with the ligase and everything else and notice that we have our selectable marker here. We’re then going to insert that into the cell using one of our four methods, probably in this case would be electroporation. And then we’re going to grow at a very small scale maybe 25 to 500 millilitres we’re going to allow these cells to divide and we’re going to select by the use of antibiotics, just the cells that contain the plasmid, which remember has the gene that’s going to contain the information to make the protein that we’re interested in. And now all of this really is pretty much research and development and a little bit of process development, but now we’re going to go into the scale-up process because 500 millilitres of cells isn’t going to make enough product to treat even one person. We need to scale this up. We need to make lots more of this particular product. So we begin a very step wise process here where we incrementally increase the volume and therefore the number of cells that we’re growing. Why do we have to do this? Because cells generally need a particular concentration from which they grow. So if I just took a few cells and added them right into the 20,000 litre bioreactor, they may not grow at all, they may just freeze up because they’re so lonely, they’re so spread out through there or they may even die. So what I have to do is incrementally increase the volume at which I’m growing the cells. We might go from 500 millilitres to 1 or 5 litres, and then from 5 litres we might go to a 100 litres and then we might go to a 1000 litres, and then to 20,000 litres. And that’s what we’re showing here. So we have our small scale culture. This is our 25 mils to 500 mils. We then go to a bench top bioreactor, these are usually anywhere from 10 to 20 litres. We then go to pilot scale and this is usually 50 to 500 litres of media. And remember if this is a CHO cell we’re talking $60 a litre. And this right here is probably a 3 to 6 week process. And then once we have the pilot scale going, we then scale all the way up into our 1000 to 20,000 litre bioreactor. And so a bioreactor is simply the name for the vessel in which we grow our cells. And these are specially designed vessels because they control things like how much oxygen is available. They control the PH that is how much acid and bases there are. They control the temperature and remember these cells are growing suspended, they’re floating around in there, but if cells are heavy so I need to stir them, so there’s a very specific stir rate that must be maintained. So all this is controlled and designed into our bioreactors. And so we scale this up. And after a month or two we’re now at our 20,000 litre scale and now we have enough cells that we’re able to produce kilograms of our therapeutic protein. And this is then called upstream processing. So from our small scale culture into the bioreactor we’re doing upstream processing. We’re essentially growing our cells, and remember as the cells grow they are producing our therapeutic BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 12 protein. So once we have our maximum number of cells, there’s no more room for them to grow, they produce as much protein as they’re going to grow. We then begin the harvest process where we do product recovery. And now, unfortunately it’s not just a single protein that’s present, but lots of different proteins because a number of the cellular proteins are also present. So we now need to do purification steps to isolate the one therapeutic protein away from all the other proteins, because those other extraneous proteins may cause side effects or an immune response into patients. So we need to have a fairly pure product. And as a final step we have what’s called fill and finish where we put the product into individual vials and we have to label that and then we ship it out to the market. Cell Banking Now we mentioned earlier that I may have spent anywhere from 1 to 10 years to produce my particular cell that has the gene in it, my recombinant gene that allows me to produce my protein product. So that cell is very precious to me and I want to make sure that nothing happens to it. So in order to preserve these cells, in order to have a readily available supply of cells when I need them, I produce a cell bank. And the idea here is that every time I start a production campaign, and that’s really what we outlined on the preceding slide, I’m going to take a new vial out of the cell bank. Because remember every time a cell divides, there’s always the potential that it could have a mutation and our product could be changed. So the FDA likes us to use cells that are, if you will, very fresh or the official term for that is they’re at a low passage number, they haven’t grown and divided very much. So we take a vial out of our cell bank and we do our whole scale up process again and then we produce our product. Cell Bank Production Now it turns out that there are really two layers to a cell bank. The first cell bank is called the Master Cell Bank, the MCB. So the Master Cell Bank is designed or derived from our original cell culture, the one that we put our plasmid in that had our recombinant gene in it and we’ve grown this up and we’ve proven that it’s pure that everything works. And then we take this and we distribute this into vials. All right, how many vials, the FDA usually likes you to have roughly 200 vials. So we freeze these vials down, and then when it’s time to start a new product, we take out one vial and we expand that into another 200 vials. So from this 1 vial, we expand this into 200 vials and this becomes what’s called a working cell bank. And then from the working cell bank we do a number of campaign runs to produce our product. The idea here is that with a properly constructed Master Cell Bank, you’ll be able to make your protein product for roughly 300 years, well beyond the expected shelf life or market life of a particular product. But again the idea of the cell bank is it protects our investment in creating the cells, which are what we are using to produce our protein. BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 13 Scale-Up And Manufacturing Process So in the scale-up in manufacturing process, again just to reiterate this, we start with our stock culture which is really our cell bank. We begin to grow this up at a small volume. We then incrementally increase this until we finally get enough volume with enough cells in it to produce kilogram quantities of product. But there are few things that we want to direct your attention here to because manufacturing a therapeutic protein by growing cells is a little different from growing cells in the lab for research. We need to worry about the FDA. So this process must be done in a way that is what we call CGMP compliant. CGMP stands for Current Good Manufacturing Practice and this is a set of guidelines outlined by the FDA to ensure quality and consistency of your cell culture product. And included as part of the CGMP guidelines are things like we need to know cell viability, cell viability is just a fancy way of saying, what percentage of your cells are alive? And ideally in most manufacturing processes you want that viability to be around 90 to 95%. There’s no sense in trying to grow cells if 80% of them are dead and it also tells you that something is wrong. You need to be able to know what the concentration of your cells are, that is how many cells in a particular volume, like how many cells per 1 millilitre are present. We want to know the concentration of protein that’s ultimately been produced and activity, this means, is the protein working or not? Because remember proteins are fairly delicate molecules, so we want to make sure that as we go through all these different steps in producing and recovering the protein that we haven’t done anything to change its 3 dimensional structure and make it non-functional. And we always have to pay attention to our growth conditions. Again, this includes things like temperature, PH, how much oxygen is present, how fast we’re stirring the cells. And you can see here in our bioreactors, these are what are called impellers, so impellers are just propellers that are inside the tank, but they are specially designed to be very gentle with our cells and then these spin around to keep the cells in suspension. And if we spin them too fast, you can imagine if would be like you sitting in your washing machine getting smashed against the side of the wall. So we have to keep the speed at a low consistent rate in order to protect the cells. Harvesting & Purification Process Once we’ve grown the cells and they’ve made the protein product, we now need to do recovery and purification. So hopefully our protein is a secreted protein and so all we have to do is turn off the stirrers, the cells all settle to the bottom and we now collect the cell culture fluid and this is called the cell free supernatant and this could be done by filtration or by centrifugation. And then once we’ve collected our cell free supernatant we usually concentrate it, because 20,000 litres is a heck of a large volume to work with. And then once we’ve done that we begin to purify the product and this is normally done using a process called chromatography. And so, chromatography takes advantage of some property of the protein that’s unique to that particular BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 14 protein and allows us to separate it from all the other proteins. So what makes one protein different from another? Well it’s the amino acid sequence which remember is determined by its gene sequence, but different amino acids have different charges on them and by this we mean plus and minus charges, just like on your battery. They have different shapes or structures and they have different sizes. Some proteins are really big and some proteins are really small. So in combination we could take advantage of these types of properties to separate one protein from another. So the idea is, in my cell free supernatant, I might have 500 to 5000 different proteins, only one of those proteins is my therapeutic product. And so what I want to do is through a series of chromatography steps I want to isolate all those proteins away until the only protein remaining is my therapeutic protein. This is our -- called our downstream process and this is our purification step. And this can be quite lengthy and quite expensive, but at the end you have a purified protein. Summary So to summarize this then, what we’ve really learned here is how to go from a gene to a recombinant protein to a therapeutic process. So recombinant DNA technology is the process or the method that we use to transfer a specific sequence of DNA, a gene, from one organism to another. And we choose the gene based on the protein that we want to make, so this could be the insulin gene, this could be the EPO gene, this could be a gene that contains the information to make a specific antibody like the Her antibody we talked about in the 101 webinar. We used either a bacteria cell or a mammalian cell to produce large quantities of proteins. So the cell is what’s actually making the protein and what we do in the manufacturing process is provide an environment that is the bioreactor to allow the cells to grow and produce their proteins. This process of growing cells to a very large volume is called bio-manufacturing and the specific process of making a therapeutic protein is called a campaign. Because it takes so much time and effort to engineer these cell lines and because we want to make sure that we have a consistent product over the years, we then freeze these lines and this is really called cell banking and we need to preserve them. Scale-up is simply the process of going from a small volume, not growing very many cells to growing huge volumes of cells and this takes place over weeks or months because it takes a while for the cells to grow. As the cells are growing they are producing the therapeutic protein, we have to recover that therapeutic protein and then we need to purify that protein so at the end all we have is a single protein, the protein that we’re going to give to the patient. So if I’m making insulin I need to make sure that at the end of my process the only protein that’s in my vial is the insulin protein or if its EPO, it’s the EPO protein. And so there’s a number of steps that have to be taken to ensure that this happens and the FDA through CGMP ensures that this process is consistent and that the protein produced is safe and free of contamination. BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 15 And that concludes our second webinar. Thank you for your attention and I hope you’re excited and ready to take the third webinar which deals with Drug Discovery. Stacey Franklin: Hi, I am Stacey Franklin, CEO and owner of Biotech Primer. This webinar series has been developed and delivered by Biotech Primer. Biotech Primer is a training company that specializes in teaching the basics of biotechnology for the non-scientist. Want to learn more? Please visit our website www.biotechpriemrinc.com to see a listing of upcoming classes or contact me to discuss customize in-house classes. Thank you. 00:57:23 [Audio Ends] BioTech Primer Inc. Copy Right 2012 Page 16