* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 0-Background

Muslim world wikipedia , lookup

War against Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Mormonism wikipedia , lookup

Reception of Islam in Early Modern Europe wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Sikhism wikipedia , lookup

Islam and violence wikipedia , lookup

Sources of sharia wikipedia , lookup

Succession to Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Islamism wikipedia , lookup

Regensburg lecture wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Islamic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Muhammad and the Bible wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Somalia wikipedia , lookup

Satanic Verses wikipedia , lookup

Censorship in Islamic societies wikipedia , lookup

Medieval Muslim Algeria wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Historicity of Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Indonesia wikipedia , lookup

Islamic ethics wikipedia , lookup

Islamic Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Origin of Shia Islam wikipedia , lookup

Schools of Islamic theology wikipedia , lookup

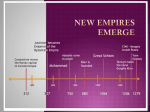

HISTORY 2 Chapter 7 The Emergence of the Islamic World and Medieval Europe From the third through the fifth centuries of the Common Era, classical civilizations across Eurasia suffered a series of crises and breakdowns. The Han Dynasty in China collapsed in 220 C.E. and the Roman Empire in the west had ruptured irreparably by 476 C.E. These transformations brought the classical era to a close and ushered in a new period in world history. In western Eurasia, the passing of the Roman Empire set the context for the emergence of two new civilizations: the feudal societies of medieval Europe and the expansive realm of Islam. Although these successors to the Roman Empire would experience continuous conflicts and confrontations over the next 1000 years, their common origins in the Hellenistic cultures of antiquity made them, in many ways, sister civilizations. 1. The Origins of Islamic Civilization The year of Mohammed’s birth, 570 C.E., was a time of transition in western Eurasia. The Roman Empire had given way to the new Germanic peoples, who would go on to shape the medieval societies of Western Europe. Meanwhile, in the east, the grip of the Persian Empire over the lands of Arabia was slipping. Muhammad began to preach sometime around 613 and won a large following among the residents of the Arabian peninsula before his death in 632. The man who succeeded to the leadership of the Islamic religious community was called the caliph (KAY-lif), literally “successor.” The caliph exercised political authority because the Muslim religious community was also a state, complete with its own government and a powerful army that conquered many neighboring regions. The first four caliphs were chosen from different clans on the basis of their ties to Muhammad, but after 661 all the caliphs came from a single clan, or dynasty, the Umayyads, who governed until 750. 1 The Life and Teachings of Muhammad, ca. 570–632 Muhammad was born into a family of merchants sometime around 570 in Mecca, a trading community in the Arabian peninsula. At the time of his birth, the two major powers of the Mediterranean world were the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian empire of the Persians. On the southern edge of the two empires lay the Arabian peninsula, which consisted largely of desert punctuated by small oases. Traders traveling from Syria to Yemen frequently stopped at the few urban settlements, including Mecca and Medina, near the coast of the Red Sea. The local peoples spoke Arabic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew that was written with an alphabet. The population was divided between urban residents and the nomadic residents of the desert, called Bedouins (BED-dwins), who tended flocks of sheep, horses, and camels. All Arabs, whether nomadic or urban, belonged to different clans who worshiped protective deities that resided in an individual tree, a group of trees, or sometimes a rock with an unusual shape. One of the most revered objects was a large black rock in a cube-shaped shrine, called the Kaaba (KAH-buh), at Mecca. Above these tribal deities stood a creator deity named Allah (AH-luh). (The Arabic word allah means “the god” and, by extension, “God.”) When, at certain times of the year, members of different clans gathered to worship individual tribal deities, they pledged to stop all feuding. During these pilgrimages to Mecca, merchants like Muhammad bought and sold their wares. Extensive trade networks connected the Arabian peninsula with Palestine and Syria, and both Jews and Christians lived in its urban centers. While in his forties and already a wealthy merchant, Muhammad had a series of visions in which he saw a figure that Muslims believe was the angel Gabriel. After God spoke to him through the angel, Muhammad called on everyone to submit to God. The religion founded on belief in this event is called Islam, meaning “submission” or “surrender.” Muslims do not call Muhammad the founder of Islam because God’s teachings, they believe, are timeless. Muhammad taught that his predecessors included all the Hebrew prophets from the Hebrew Bible as well as Jesus and his disciples. Muslims consider Muhammad the last messenger of God, however, and historians place the beginning date for Islam in the 610s because no one thought of himself or herself as Muslim before Muhammad received his revelations. Muhammad’s earliest followers came from his immediate family: his 2 wife Khadijah (kah-DEE-juh) and his cousin Ali, whom he had raised since early childhood. Unlike the existing religion of Arabia, but like Christianity and Judaism, Islam was monotheistic; Muhammad preached that his followers should worship only one God. He also stressed the role of individual choice: each person had the power to decide to worship God or to turn away from God. Men who converted to Islam had to undergo circumcision, a practice already widespread throughout the Arabian peninsula. Islam developed within the context of Bedouin society, in which men were charged with protecting the honor of their wives and daughters. Accordingly, women often assumed a subordinate role in Islam. In Bedouin society, a man could repudiate his wife by saying “I divorce you” three times. Although women could not repudiate their husbands in the same way, they could divorce an impotent man. Although Muhammad recognized the traditional right of men to repudiate their wives, he introduced several measures aimed at improving the status of women. For example, he set the number of wives a man could take at four. His supporters explained that Islamic marriage offered the secondary wives far more legal protection than if they had simply been the unrecognized mistresses of a married man, as they were before Muhammad’s teachings. He also banned the Bedouin practice of female infanticide. Finally, he instructed his female relatives to veil themselves when receiving visitors. Although many in the modern world think the veiling of women an exclusively Islamic practice, women in various societies in the ancient world, including Greeks, Mesopotamians, and Arabs, wore veils as a sign of high station. Feuding among different clans was a constant problem in Bedouin society. In 620, a group of nonkinsmen from Medina, a city 215 miles (346 km) to the north, pledged to follow Muhammad’s teachings in hopes of ending the feuding. Because certain clan leaders of Mecca had become increasingly hostile to Islam, even threatening to kill Muhammad, in 622 Muhammad and his followers moved to Medina. Everyone who submitted to God and accepted Muhammad as his messenger became a member of the umma (UM-muh), the community of Islamic believers. This migration, called the hijrah (HIJ-ruh), marked a major turning point in Islam. All dates in the Islamic calendar are calculated from the year of the hijrah. 3 Muhammad began life as a merchant, became a religious prophet in middle age, and assumed the duties of a general at the end of his life. In 624, Muhammad and his followers fought their first battle against the residents of Mecca. Muhammad said that he had received revelations that holy war, whose object was the expansion of Islam—or its defense––was justified. He used the word jihad (GEEhahd) to mean struggle or fight in military campaigns against non--Muslims. (Modern Muslims also use the term in a more spiritual or moral sense to indicate an individual’s striving to fulfill all the teachings of Islam.) In 630, Muhammad’s troops conquered Mecca and removed all tribal images from the pilgrimage center at the Kaaba. Muhammad became ruler of the region and exercised his authority by adjudicating among feuding clans. The clans, Muhammad explained, had forgotten that the Kaaba had originally been a shrine to God dedicated by the prophet Abraham (Ibrahim in Arabic) and his son Ishmael. Muslims do not accept the version of Abraham’s sacrifice given in the Old Testament, in which Abraham spares Isaac at God’s command. In contrast, Muslims believe that Abraham offered God another of his sons: Ishmael, whose mother was the slave woman Hajar (Hagar in Hebrew). The pilgrimage to Mecca, or hajj (HAHJ), commemorates that moment when Abraham freed Ishmael and sacrificed a sheep in his place. Later, Muslims believe, Ishmael fathered his own children, the ancestors of the clans of Arabia. The First Caliphs and the Sunni-Shi’ite Split, 632–661 Muhammad preached his last sermon from Mount Arafat outside Mecca and then died in 632. He left no male heirs, only four daughters, and did not designate a successor, or caliph. Clan leaders consulted with each other and chose Abu Bakr (ah-boo BAHK-uhr) (ca. 573–634), an early convert and the father of Muhammad’s second wife, to lead their community. Although not a prophet, Abu Bakr held political and religious authority and also led the Islamic armies. Under Abu Bakr’s skilled leadership, Islamic troops conquered all of the Arabian peninsula and pushed into present-day Syria and Iraq. When Abu Bakr died only two years after becoming caliph, the Islamic community again had to determine a successor. This time the umma chose Umar ibn alKhattab (oo-MAHR ibin al–HAT-tuhb) (586?–644), the father of Muhammad’s third wife. Muslims brought their disputes to Umar, as they had to Muhammad. 4 During Muhammad’s lifetime, a group of Muslims had committed all of his teachings to memory, and soon after his death they began to compile them as the Quran (also spelled Koran), which Muslims believe is the direct word of God as revealed to Muhammad. In addition, early Muslims recorded testimony from Muhammad’s friends and associates about his speech and actions. In the Islamic textual tradition, these reports, called hadith (HAH-deet) in Arabic, are second in importance only to the Quran (kuh-RAHN). Umar reported witnessing an encounter between Muhammad and the angel Gabriel in which Muhammad listed the primary obligations of each Muslim, which have since come to be known as the Five Pillars of Islam, specified in the definition in the margin. (See the feature “Movement of Ideas: The Five Pillars of Islam.”) When Umar died in 644, the umma chose Uthman to succeed him. Unlike earlier caliphs, Uthman was not perceived as impartial, and he angered many by giving all the top positions to members of his own Umayyad clan. In 656, a group of soldiers mutinied and killed Uthman. With their support, Muhammad’s cousin Ali, who was also the husband of his daughter Fatima, became the fourth caliph. But Ali was unable to reconcile the different feuding groups, and in 661 he was assassinated. Ali’s martyrdom became a powerful symbol for all who objected to the reigning caliph’s government. The political division that occurred with Ali’s death led to a permanent religious split in the Muslim community. The Sunnis held that the leader of the Islamic community could be chosen by consensus and that the only legitimate claim to descent was through the male line. In Muhammad’s case, his uncles could succeed him, since he left no sons. Although Sunnis accept Ali as one of the four rightly guided caliphs that succeeded Muhammad, they do not believe that Ali and Fatima’s children, or their descendants, can become caliph because their claim to descent was through the female line of Fatima. Opposed to the Sunnis were the “shia” or “party of Ali,” usually referred to as Shi’ites in English, who believed that the grandchildren born to Ali and Fatima should lead the community. They denied the legitimacy of the three caliphs before Ali, who were related to Muhammad only by marriage, not by blood. The breach between Sunnis and Shi’ites became the major fault line within Islam that has existed down to the present. (Today, Iran, Iraq, and Bahrain are 5 predominantly Shi’ite, and the rest of the Islamic world is mainly Sunni.) The two groups have frequently come into conflict. Early Conquests, 632–661 The early Muslims forged a powerful army that attacked non-Muslim lands, including the now-weak Byzantine and Persian Empires, with great success. When the army attacked a new region, the front ranks of infantry advanced using bows and arrows and crossbows. Their task was to break into the enemy’s frontlines so that the mounted cavalry, the backbone of the army, could attack. The caliph headed the army, which was divided into units of one hundred men and subunits of ten. Once the Islamic armies pacified a new region, the Muslims levied the same tax rates on conquering and conquered peoples alike, provided that the conquered peoples converted to Islam. Islam stressed the equality of all believers before God, and all Muslims, whether born to Muslim parents or converts, paid two types of taxes: one on the land, usually fixed at one-tenth of the annual harvest, and a property tax with different rates for different possessions. Because the revenue from the latter was to be used to help the needy or to serve God, it is often called an “alms-tax” or “poor tax.” Exempt from the alms tax, non-Muslims paid a tax on each individual, usually set at a higher rate than the taxes paid by Muslims. Islamic forces conquered city after city and ruled the entire Arabian peninsula by 634. Then they crossed overland to Egypt from the Sinai Peninsula. By 642, the Islamic armies controlled Egypt, and by 650 they controlled an enormous swath of territory from Libya to Central Asia. In 650, they vanquished the once-powerful Sasanian empire. The new Islamic state in Iran aspired to build an empire as large and long-lasting as the Sasanian empire, which had governed modern-day Iran and Iraq for more than four centuries. The caliphate’s armies divided conquered peoples into three groups. Those who converted became Muslims. Those who continued to adhere to Judaism or Christianity were given the status of “protected subjects” (dhimmi in Arabic), because they too were “peoples of the book” who honored the same prophets from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament that Muhammad had. Non-Muslims and nonprotected subjects formed the lowest group. Dhimmi status was later extended to Zoroastrians as well. 6 The Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750 By 661 Muslims had created their own expanding empire whose religious and political leader was the caliph. After Ali was assassinated in 661, Muawiya, a member of the Umayyad clan like the caliph Uthman, unified the Muslim community. In 680, when he died, Ali’s son Husain tried to become caliph, but Muawiya’s son defeated him and became caliph instead. Since only members of this family became caliphs until 750, this period is called the Umayyad dynasty. The Umayyads built their capital at Damascus, the home of their many Syrian supporters, not in the Arabian peninsula. Initially, they used local languages for administration, but after 685 they chose Arabic as the language of the empire. In Damascus, the Umayyads erected the Great Mosque on the site of a church housing the relics of John the Baptist. Architects modified the building’s Christian layout to create a large space where devotees could pray toward Mecca. This was the first Islamic building to have a place to wash one’s hands and feet, a large courtyard, and a tall tower, or minaret, from which Muslims issued the call to prayer. Since Muslims honored the Ten Commandments, including the Second Commandment, “You shall not make for yourself a graven image,” the Byzantine workmen depicted no human figures or living animals. Instead their mosaics showed landscapes in an imaginary paradise. The Conquest of North Africa, 661–750 Under the leadership of the Umayyads, Islamic armies conquered the part of North Africa known as the Maghrib—modern-day Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia— between 670 and 711, and then crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to enter Spain. Strong economic and cultural ties dating back to the Roman Empire bound the Maghrib to western Asia. Its fertile fields provided the entire Mediterranean with grain, olive oil, and fruits like figs and bananas. In addition, the region exported handicrafts such as textiles, ceramics, and glass. Slaves and gold moved from the interior of Africa to the coastal ports, where they, too, were loaded into ships crossing the Mediterranean. Arab culture and the religion of Islam eventually took root in North Africa, expanding from urban centers into the countryside. By the tenth century, Christians had become a minority in Egypt, outnumbered by Muslims, and by the twelfth century, Arabic had replaced both Egyptian and the Berber languages of the Maghrib as the dominant language. Annual performance of the hajj pilgrimage 7 strengthened the ties between the people of North Africa and the Arabian peninsula. Pilgrim caravans converged in Cairo, from which large groups then proceeded to Mecca. Islamic rule reoriented North Africa. Before it, the Mediterranean coast of Africa formed the southern edge of the Roman Empire, where Christianity was the dominant religion and Latin the language of learning. Under Muslim rule, North Africa lay at the western edge of the Islamic realm, and Arabic was spoken everywhere. The Abbasid Caliphate, 750–945 In 744, a group of Syrian soldiers assassinated the Umayyad caliph, prompting an all-out civil war among all those hoping to control the caliphate. In 750, a section of the army based in western Iran, in the Khurasan region, triumphed and then shifted the capital some 500 miles (800 km) east from Damascus to Baghdad, closer to their base of support. Because the new caliph claimed descent from Muhammad’s uncle Abbas, the new dynasty was called the Abbasid dynasty and their empire the Abbasid caliphate. Under Abbasid rule, the Islamic empire continued to expand east into Central Asia. At its greatest extent, it included present-day Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, southern Pakistan, and Uzbekistan. In Spain, however, the leaders of the vanquished Umayyad clan established a separate Islamic state. The Rise of Regional Centers Under the Abbasids, 945–1258 The Abbasid Caliphs eventually lost control over the Islamic realm as regional leaders broke away. Muslims found it surprisingly easy to accept the new division of political and religious authority. The caliphs continued as the titular heads of the Islamic religious community, but they were entirely dependent on local rulers for financial support. No longer politically united, the Islamic world was still bound by cultural and religious ties, including the obligation to perform the hajj. Under the leadership of committed Muslim rulers, Islam continued to spread throughout South Asia and the interior of Africa, and Islamic scholarship and learning continued to thrive. In 1055, Baghdad fell to a group of soldiers from Central Asia, the Turkish-speaking Seljuqs (also spelled Seljuks, and pronounced (sell-JOOKs). Other sections of the empire broke off and, like Baghdad, experienced rule by different dynasties. In most periods, the former Abbasid Empire was divided into four regions: the former 8 heartland of the Euphrates and Tigris River basins; Egypt and Syria; North Africa and Spain; and the Amu Darya and Syr Daria River Valleys in Central Asia. Two centuries of Abbasid rule had transformed these four regions into Islamic realms whose residents, whether Sunni or Shi’ite, observed the tenets of Islam. Their societies retained the basic patterns of Abbasid society. When Muslims traveled anywhere in the former Abbasid territories, they could be confident of finding mosques, being received as honored guests, and having access to the same basic legal system. As in the Roman Empire, where Greek and Latin prevailed, just two languages could take a traveler through the entire realm: Arabic, the language of the Quran and high Islamic learning, and Persian, the Iranian language of much poetry, literature, and history. Pilgrimage to Mecca By the twelfth century, different Islamic governments ruled the different sections of the former Abbasid Empire. Since the realm of Islam was no longer unified, devout Muslims had to cross from one Islamic polity to the next as they performed the hajj. The most famous account of the hajj is The Travels of Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217), a courtier from Granada, Spain, who went on the hajj in 1183–1185. Ibn Jubayr’s book serves as a guide to the sequence of hajj observances that had been fixed by Muhammad; Muslims today continue to perform the same rituals. Once pilgrims arrived in Mecca, they walked around the Kaaba seven times in a counterclockwise direction. On the eighth day of the month Ibn Jubayr and all the other pilgrims departed for Mina, which lay halfway to Mount Arafat. The hajj celebrated Abraham’s release of his son Ishmael. The most important rite, the Standing, commemorated the last sermon given by the prophet Muhammad. The hajj may have been a religious duty, but it also had a distinctly commercial side: merchants from all over the Islamic world found a ready market among the pilgrims. Ibn Jubayr then traveled along Zubaydah’s Road to Baghdad, where he visited the palace where the family members of the caliph “live in sumptuous confinement.” Ibn Jubayr portrays the Islamic world in the late twelfth century, when the Abbasid caliphs continued as figureheads in Baghdad but all real power lay with different regional rulers. This arrangement came to an abrupt end in 1258, when the Mongols invaded Baghdad and ended even that minimal symbolic role for the caliph. 9 2. The Emergence of Medieval Europe The collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century ushered in a far-reaching transformation of western societies. The urban, classical, pagan culture of antiquity gradually gave way to agrarian, Germanic, Christian societies with far different structures and outlooks. Although important links to the classical past would continue to influence the emerging civilizations of Europe, it was clear by the end of the sixth century that the western regions of the old Roman Empire were moving in a new direction. The new civilization of medieval Europe differed from its Roman predecessor in a number of important aspects. The most significant differences were the declining role of cities and the absence of cohesive, centralized government. Urban centers shrank and sometimes disappeared completely in the transition to the more agrarian-based agricultural societies of the medieval era. In addition, the collapse of the centralized administrative apparatus of the Roman State meant that new arrangements would have to be improvised to meet the basic needs of government and the provision of social services. The system that evolved in early medieval Europe to address these new conditions is generally called feudalism. Land Use and Social Change, 1000–1350 Sharp increases in agricultural productivity brought dramatic changes throughout early European society. These changes did not occur everywhere at the same time, and in some areas they did not occur at all, but they definitely took place in northern France between 1000 and 1200. One change was that slavery all but disappeared, while serfs did most of the work for those who owned land. Although their landlords did not own them, and they were not slaves, a series of obligations tied serfs to the land. Each year, their most important duty was to give their lord a fixed share of the crop and of their herds. Serfs were also obliged to build roads, give lodging to guests, and perform many other tasks for their lords. After 1000, a majority of those working the land became serfs. Many serfs lived in settlements built around either the castles of lords or churches. The prevailing mental image of a medieval castle town is one in which a lord lives protected by his knights and surrounded by his serfs, who go outside the walls each day to work in the fields. 10 The prominent French historian Georges Duby has described the social revolution of the eleventh and twelfth centuries in the following way. In Carolingian society, around 800, the powerful used loot and plunder to support themselves, usually by engaging in military conquest. Society consisted of two major groups: the powerful and the powerless. In the new society after 1000, the powerful comprised several clearly defined social orders—lords, knights, clergy—who held specific rights over the serfs below them. Many lords also commanded the service of a group of warriors, or knights, who offered them military service in exchange for military protection from others. Knights began their training as children, when they learned how to ride and to handle a dagger. At the age of fourteen, knights-in-training accompanied a mature knight into battle. They usually wore tunics made of metal loops, or chain mail, as well as headgear that could repel arrows. Their main weapons were iron-and-steel swords and crossbows that shot metal bolts. One characteristic of the age was weak centralized rule. Although many countries, like England and France, continued to have monarchs, their power was severely limited because their armies were no stronger than those of the nobles who ranked below them. They controlled the lands immediately under them but not much else. The king of France, for example, ruled the region in the immediate vicinity of Paris, but other nobles had authority over the rest of France. In other countries as well, kings vied with rival nobles to gain control of a given region, and they often lost. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, landowners frequently gave large tracts of land to various monasteries (discussed later in this chapter). The monasteries did not pay any taxes on this land, and no one dared to encroach on church-owned land for fear of the consequences from God. By the end of the twelfth century, the church owned one-third of the land in northern France and one-sixth of all the land in France and Italy combined. The Movement for Church Reform, 1000–1300 Although historians often speak of the church when talking about medieval Europe, no single, unified entity called the church existed. The pope in Rome presided over many different local churches and monasteries, but he was not consistently able to enforce decisions. Many churches and monasteries throughout Europe possessed their own lands and directly benefited from the greater yields of cerealization. In addition, devotees often gave a share of their increasing personal wealth to 11 religious institutions. As a result, monastic leaders had sufficient income to act independently, whether or not they had higher approval. Starting in 1000, different reformers tried to streamline the church and reform the clergy. Yet reform from within did not always succeed. The new begging orders founded in the thirteenth century, like the Franciscans and the Dominicans, explicitly rejected what they saw as lavish spending. The Structure of the Church By 1000, the European countryside was completely blanketed with churches, each one the center of a parish in which the clergy lived together with laypeople. Some churches were small shrines that had little land of their own, while others were magnificent cathedrals. The laity were expected to pay a tithe of 10 percent of their income to their local parish priest, and he in turn performed the sacraments for each individual as he or she passed through the major stages of life: baptism at birth, confirmation and marriage at young adulthood, and funeral at death. The parish priest also gave communion to his congregation. By the year 1000, this system had become so well established in western Europe that no one questioned it, much as we agree to the obligation of all citizens to pay taxes. The clergy fell into two categories: the secular clergy and the regular clergy. The secular clergy worked with the laity as local priests or schoolmasters. Regular clergy lived in monasteries by the rule, or regula in Latin, of the church or monastic order. Reform from Above In 1046, one of three different Italian candidates vying for the position of pope had bought the position from an earlier pope who decided that he wanted to marry. Such simony was universally considered a sin. The ruler of Germany, Henry III (1039–1056), intervened in the dispute and named Leo IX pope (in office between 1048 and 1056). Leo launched a reform campaign with the main goals of ending simony and enforcing celibacy. Not everyone agreed that marriage of the clergy should be forbidden. Many priests’ wives came from locally prominent families who felt strongly that their female kin had done nothing wrong in marrying a member of the clergy. Those who supported celibacy believed that childless clergy would have no incentive to divert church property toward their own family, and their view eventually prevailed. 12 Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085) also sought to reform the papacy by drafting twentyseven papal declarations asserting the supremacy of the pope. Only the pope could decide issues facing the church, Gregory VII averred, and only the pope had the right to appoint bishops. Many of the twenty-seven points had been realized by 1200 as more Europeans came to accept the pope’s claim to be head of the Christian church. In 1215, Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) presided over the fourth Lateran Council. More than twelve hundred bishops, abbots, and representatives of different European monarchs met in the Lateran Palace in the Vatican to pass decrees regulating Christian practice, some of which are in effect today. For example, they agreed that all Christians should receive Communion at least once a year and should also confess their sins annually. The fourth Lateran Council marked the high point of the pope’s political power; subsequent popes never commanded such power over secular leaders. Reform Outside the Established Orders As the drive to reform continued, some asked members of religious orders to live exactly as Jesus and his followers had, not in monasteries with their own incomes but as beggars dependent on ordinary people for contributions. Between 1100 and 1200, reformers established at least nine different begging orders, the most important of which was the Franciscans founded by Saint Francis of Assisi (ca. 1181–1226). Members of these orders were called friars. The Franciscan movement grew rapidly even though Francis allowed none of his followers to keep any money, to own books or extra clothes, or to live in a permanent dwelling. In 1217, Francis had 5,000 followers; by 1326, some 28,000 Franciscans were active. Francis also created the order of Saint Clare for women, who lived in austere nunneries where they were not allowed to accumulate any property of their own. In 1215, Saint Dominic (1170?–1221) founded the order of Friars Preachers in Spain. Unlike Francis, he stressed education and sent some of his brightest followers to the new universities. Thomas Aquinas (1224/25–1274), one of the most famous scholastic thinkers, belonged to the Dominican order. Aquinas wrote Summa Theologica (Summary of Theology), a book juxtaposing the teachings of various church authorities on a range of difficult questions. Aquinas wrote detailed explanations that remained definitive for centuries. 13 3. The Crusades, 1095–1291 The founding of the Franciscans and the Dominicans was only one aspect of a broader movement to spread Christianity through Crusades. Some Crusades within Europe targeted Jews, Muslims, and members of other non-Christian groups. In addition, the economic surplus resulting from cerealization and urban growth financed a series of expeditions to the Holy Land to try to conquer Jerusalem, the symbolic center of the Christian world because Jesus had preached and died there, and make it Christian again. The Crusaders succeeded in conquering Jerusalem but held it for only eighty-eight years. The Crusades to the Holy Land Historians use the term Crusades to refer to the period between 1095, when the pope first called for Europeans to take back Jerusalem, and 1291, when the last European possession in Syria was lost. The word Crusader referred to anyone belonging to a large, volunteer force against Muslims. In 1095, Pope Urban II (1088–1099) told a large meeting of church leaders that the Byzantine emperor requested help against the Seljuq Turks. He urged those assembled to recover the territory lost to “the wicked race” (meaning Muslims). If they died en route, the pope promised, they could be certain that God would forgive their sins because God forgave all pilgrims’ sins. This marked the beginning of the First Crusade. An estimated 50,000 combatants responded to the pope’s plea in 1095; of these, only 10,000 reached Jerusalem. The Crusader forces consisted of self-financed individuals who, unlike soldiers in an army, did not receive pay and had no line of command. Nevertheless, the Crusaders succeeded in taking Jerusalem in 1099 from the rulers of Egypt, who controlled it at the time. After Jerusalem fell, the out-ofcontrol troops massacred everyone still in the city. The Crusaders ruled Jerusalem as a kingdom for eighty-eight years, long enough that the first generation of Europeans died and were succeeded by generations who saw themselves first as residents of Outremer (OU-truh-mare), the term the Crusaders used for the eastern edge of the Mediterranean. Even though Jerusalem was also a holy site for both Jews and Muslims, the Crusaders were convinced that the city belonged to them. This assumption was challenged by a man named Saladin, whose father had served in the Seljuq army. In 1169 Saladin overthrew the reigning Egyptian dynasty, and in 14 1171 he founded the Ayyubid dynasty. His biographer explained the extent of Saladin’s commitment to jihad, or holy war against the Crusaders: The Holy War and the suffering involved in it weighed heavily on his heart and his whole being in every limb: he spoke of nothing else, thought only about equipment for the fight, was interested only in those who had taken up arms. Saladin devoted himself to raising an army strong enough to repulse the Crusaders, and by 1187 he had gathered an army of thirty thousand men on horseback carrying lances and swords like knights but without chain-mail armor. Saladin trapped and defeated the Crusaders in an extinct Syrian volcano called the Horns of Hattin. When his victorious troops took Jerusalem back, they restored the mosques as houses of worship and removed the crosses from all Christian churches, although they did allow Christians to visit the city. Subsequent Crusades failed to recapture Jerusalem, but in 1201, the Europeans decided to make a further attempt in the Fourth Crusade. In June 1203, the Crusaders reached Constantinople and were astounded by its size: the ten biggest cities in Europe could easily fit within its imposing walls, and its population surpassed 1 million. One awe-struck soldier wrote home: “If anyone should recount to you the hundredth part of the richness and the beauty and the nobility that was found in the abbeys and in the churches and the palaces and in the city, it would seem like a lie and you would not believe it.” However, when Byzantine leaders refused to help pay their transport costs, Crusade leaders commanded their troops to attack and plunder the city. One of the worst atrocities in world history resulted: the Crusaders rampaged throughout the beautiful city, killing all who opposed them, raping thousands of women, and treating the Eastern Orthodox Christians of Constantinople precisely as if they were the Muslim enemy. The Crusaders’ conduct in Constantinople turned the diplomatic dispute between the two churches, which had begun in 1054, into a genuine and lasting schism between Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox adherents. Europeans did not regain control of Jerusalem, but the Crusades provided an important precedent that the conquest and colonization of foreign territory for Christianity was acceptable. Europeans would follow this precedent when they went to new lands in Africa and the Americas. 15 The Crusades Within Europe European Christians, convinced that they were right about the superiority of Christianity, also attacked enemies within Europe, sometimes on their own, sometimes in direct response to the pope’s command. Many European Christians looked down on Jews, who were banned from many occupations, could not marry Christians, and often lived in separate parts of cities, called ghettos. But before 1095, Christians had largely respected the right of Jews to practice their own religion. This fragile coexistence fell apart in 1096, as the out-ofcontrol crowds traveling through on the First Crusade attacked the Jews living in the three German towns of Mainz, Worms, and Speyer and killed all who did not convert to Christianity. Thousands died in the violence. Anti-Jewish prejudice worsened over the next two centuries; England expelled the Jews in 1290 and France in 1306. These spontaneous attacks on Jews differed from two campaigns launched by the pope against enemies of the church. The first was against the Cathars, a group of Christian heretics who lived in the Languedoc region of southern France. Like the Zoroastrians of Iran, the Cathars believed that the forces of good in the spiritual world and of evil in the material world were engaged in a perpetual fight for dominance. In 1208, Pope Innocent III launched a crusade to Languedoc in which the pope’s forces gradually killed many of the lords and bishops who supported Catharism. In an effort to identify other enemies of the church, in the early thirteenth century the pope established a special court, called the inquisition, to hear charges against accused heretics. Unlike other church courts, which operated according to established legal norms, the inquisition used anonymous informants, forced interrogations, and torture to identify heretics. Those found guilty were usually burned at the stake. In 1212 the pope approved a crusade against non-Christians in Spain. Historians use the Spanish word Reconquista (“Reconquest”) to refer to these military campaigns by Christians against the Muslims of Spain and Portugal. The Crusader army won a decisive victory in 1212 and captured Córdoba and Seville in the following decades. After 1249, only the kingdom of Granada, on the southern tip of Spain, remained Muslim. 16