* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ( ! ) Notice: Undefined index

Schizoaffective disorder wikipedia , lookup

Depersonalization disorder wikipedia , lookup

Panic disorder wikipedia , lookup

Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Pyotr Gannushkin wikipedia , lookup

Separation anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Spectrum disorder wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar II disorder wikipedia , lookup

Narcissistic personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Conversion disorder wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Rumination syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Generalized anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

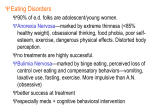

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 16/06/2017. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Fisioterapia. 2014;36(2):55---57 www.elsevier.es/ft EDITORIAL The importance of physiotherapy within the multidisciplinary treatment of eating disorders La importancia de fisioterapia dentro del tratamiento multidisciplinar de trastornos alimentarios Why should patients with eating disorders receive physiotherapy? Anorexia and bulimia nervosa Eating disorders are characterised by disturbances in eating behaviour often accompanied by feelings of distress and concerns about one’s body weight or shape1 . Anorexia and bulimia nervosa are two major formal diagnostic categories of eating disorders1 . Anorexia nervosa is is characterised by a distorted body image and excessive dieting that leads to severe weight loss with a pathological fear of becoming fat. Excessive exercise affects up to 80% of anorexia nervosa patients and has been associated with negative emotionality2 . The core feature of bulimia nervosa is loss of control over the eating behaviour resulting in binge eating and purging. Binge eating involves taking in an abnormally large quantity of food in a discrete time period and feeling a lack of control during the episode1 . Compensatory behaviours occur after a binge and might include vomiting, laxative or other diet medication use, fasting, or excessive exercise1 . Often, patients with bulimia nervosa eat at irregular intervals, and long periods of fasting trigger food cravings and then binge/purge cycles1 . It is known that cultural, social, and interpersonal factors can trigger onset of the illnesses, while changes in neural networks can sustain anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Both eating disorders are also associated with significant impairment of physical health and psychosocial functioning and carry increased risk of death3 . The physical abnormalities seen in anorexia nervosa seem to be largely secondary to these patients’ disturbed eating habits and their compromised nutritional state3 . Hence most impairments are reversed by restoration of healthy eating habits and sound nutrition, with the possible exception of reduced bone density. The main physical features of anorexia nervosa include decreased bone integrity (osteopenia leading to osteoporosis), weak proximal muscles, bradycardia, gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness and syncope and amenorrhea3 . The physical abnormalities seen in bulimia nervosa are usually minor unless vomiting, or laxative or diuretic misuse are frequent, in which case there is risk of electrolyte disturbance3 . Anorexia and bulimia nervosa also present with psychiatric co-morbidity in a number of important areas, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders (obsessivecompulsive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, other phobias, and post-traumatic stress disorder) and substance abuse3 . Because of co-morbid physical and psychiatric conditions, anorexia and bulimia nervosa have been characterised as one of the most difficult psychiatric conditions to treat. Binge Eating Disorder Binge eating disorder (BED) is included in the last edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Mental Disorders (DSM)1 . It is characterised by frequent and persistent episodes of binge eating accompanied by feelings of loss of control and marked distress in the absence of regular compensatory behaviours. Furthermore, binge eating episodes are associated with 3 or more of the following: (a) eating much more rapidly than normal, (b) eating until uncomfortably full, (c) eating large amounts of foods when not feeling physically hungry, (d) eating alone because of being embarrassed by how much one is eating, and (e) feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty after overeating. To meet the DSM criteria1 , the binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. Physical consequences of BED are largely due to a co-morbid obesity and a sedentary lifestyle4 . Obese individuals with BED also demonstrate a greater eating disorder psychopathology, i.e. expressing more weight and shape concerns and body dissatisfaction, increased emotional eating, and lower 0211-5638/$ – see front matter © 2014 Asociación Española de Fisioterapeutas. Published by Elsevier España, S.L. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ft.2014.01.002 Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 16/06/2017. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. 56 self-esteem compared with obese people without BED3 . In addition, obese persons with BED have an elevated risk for developing depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse compared to obese people without BED3 . What is the scientific evidence for physiotherapy within the treatment of eating disorders? Evidence in anorexia and bulimia nervosa A recent systematic review5 including 8 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and involving 213 patients (age-range: 16-36 years) concluded that aerobic and resistance training result in significantly increased muscle strength, body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage in anorexia patients. In addition, aerobic exercise, yoga, massage and basic body awareness therapy significantly lowered scores of eating pathology and depressive symptoms in both anorexia and bulimia nervosa patients5 . In particular the use of aerobic exercises in the treatment for anorexia nervosa is not without controversy. Many patients with anorexia nervosa engage in excessive exercise, which can contribute to ongoing weight loss. Clinicians often attempt to restrain exercise in these patients, given that it can play a role in the pathogenesis as well as progression of the disorder. However, the current literature5 indicates that those who exercise increase in weight and body fat compared with non-exercisers. There are several plausible explanations for the observed weight gain results. First, participation in exercise-based physiotherapy programmes may help to alleviate anxiety and increase comfort with gaining weight. Second, being given the opportunity to exercise during treatment might increases overall compliance with the entire treatment programme, including adherence to meal plans. Third, patients in an exercise-based physiotherapy programme are probably less likely to exercise surreptitiously with a focus on burning calories, whereas patients without opportunity to participate in a supervised exercise setting may exercise less at a level that is detrimental to their health and focused on burning calories. Exercise-based physiotherapy may also benefit patients with bulimia nervosa, and this in two ways5 . First, it may facilitate complete abstinence through psychological pathways related to the recreational nature of the activity itself. For example, the literature5 demonstrates that those who exercise experience less anxiety and depressive symptoms. Second, it may contribute to body image improvements. Bulimic patients who exercise may experience less body dissatisfaction and a reduction of the uncomfortable internal sensations of bloating and distention during eating. Evidence in binge eating disorder The evidence on physiotherapy in persons with BED is limited to 3 RCTs involving 211 female community patients (agerange: 25-63years)6 . The limited literature on physiotherapy EDITORIAL in persons with BED however clearly demonstrates that aerobic and yoga exercises reduce the number of binges and BMI of BED patients. Aerobic exercise also reduces depressive symptoms 6 . Only combining cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with aerobic exercise and not CBT alone reduces BMI6 . Combining aerobic exercise with CBT is more effective in reducing depressive symptoms than CBT alone. Adding exercise to CBT may benefit binge eaters in two ways, and this by two different mechanisms6 . First, it may facilitate abstinence from binge-eating through psychological pathways related to the recreational nature of the activity itself, i.e. those who exercise reported to experience less depressive symptoms. Secondly, physical activity may buffer the effect that anxiety sensitivity (i.e. a fear of anxiety and related sensations) has on binge eating. General recommendations based on the current scientific evidence The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines7 recommend that people with eating disorders should first be offered community- and outpatienttreatment and that inpatient care be used for those who do not respond or who present with high risk. The current evidence clearly demonstrates that physiotherapists could have a role within these first-stage community settings. Clear guidance regarding the type of physiotherapy intervention (aerobic exercise or yoga-related interventions) and optimal dose is however at the moment limited by the small number of available RCTs and the variability of the interventions themselves in terms of frequency, intensity, and duration. Physiotherapists should therefore assess the types of exercises or techniques that would best fit a person’s preferences8 . Probst et al.9 recently formulated 4 general recommendations for physiotherapists working with eating disorder patients: Physiotherapists should offer a safe and well-structured framework in which everybody knows the engagements and in which the physiotherapist constantly provides information related to the goals and content of the programme. Within a physiotherapy approach, psycho-education regarding bodily functions is an important issue. For example, it is important to explain the functions of the respiratory system during breathing exercises. The therapist’s role should also consist of thoroughly explaining that weight gain is not synonymous with feeling fat, but with health, attractiveness, and expressiveness. Other topics for psychoeducation are basic anatomy/physiology, osteoporosis, body and sensory awareness, stress, anxiety, and coping strategies, normal healthy physical activity versus maladaptive physical activity, and the influences of the media on sociocultural ideals. Whenever possible, physiotherapists should design their exercises in such a way that the patients can also try these exercises outside the therapy-sessions, on their own, or with a partner. This can be successfully done with breathing exercises, relaxation training, and stress coping strategies. It is important that patients assume responsibility for their therapy. Physiotherapists should invite their patients to express any feelings they experience during the exercises and should Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 16/06/2017. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. EDITORIAL 57 encourage patients to further deal with their feelings in for example associated psychotherapy sessions. Continual exposure to body-oriented situations in physiotherapy will enable patients to discover any changing attitudes during the exercises and will enable them to become familiar with these changes. Visual feedback with for example mirrorand video-exposure intensifies the kinesthetic sensations by providing a new perspective on the body. The underlying message of all exercises and discussions is self-respect, which will enable the patients to build up love and respect for their own body. For this purpose, it is important that during the physiotherapy sessions, the patients become aware that in addition to outward appearance, there are other values and personal aspects that are at least equally important in life. In conclusion, it is unequivocal that the role of physiotherapists in the multidisciplinary treatment of eating disorders should be further promoted. Governments should address funding for necessary physiotherapy service improvements. The Spanish Physiotherapy Association should take the lead in bridging the collaboration gap between physical and mental health care by promoting a policy of coordinated and integrated mental and physical health care including physiotherapy for all persons with eating disorders. The integration of physiotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders with an ultimate goal of providing optimal treatment to this vulnerable patient population, will be an important challenge for the Spanish Physiotherapy Association. Davy Vancampfort a,b,∗ , Michel Probst a,b University Psychiatric Centre KU Leuven, campus Kortenberg, KULeuven Department of Neurosciences, Belgium b KU Leuven Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Leuven, Belgium a Conflicts of interest Davy Vancampfort is funded by Foundation---Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen). 2. Vansteelandt K, Pieters G, Probst M, Vanderlinden J. Drive for thinness, affect regulation and physical activity in eating disorders: a daily life study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45: 1717---34. 3. Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2010;375:583---93. 4. Vancampfort D, Vanderlinden J, Stubbs B, Soundy A, Pieters G, De Hert M, et al. Physical activity correlates in persons with binge eating disorder: a systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22:1---8. 5. Vancampfort D, Vanderlinden J, De Hert M, Adámkova M, Skjaerven LH, Matamoros DC, et al. A systematic review on physical therapy interventions for patients with binge eating disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:2191---6. 6. Vancampfort D, Vanderlinden J, De Hert M, Soundy A, Adámkova M, Skjaerven LH, Catalán Matamoros D., et al. A systematic review of physical therapy interventions for patients with anorexia and bulemia nervosa. Disabil Rehabil 2013; in press. 7. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National Clinical Practice Guideline: eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and related eating disorders. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2004. 8. Probst M, Knapen J, Poot G, Vancampfort D. Psychomotor therapy and psychiatry: What is in a name? Open Complement Med J. 2010;2:105---13. 9. Probst M, Majewski ML, Albertsen MN, Catalan-Matamoros D, Danielsen M, De Herdt A, et al. Physiotherapy for patients with anorexia nervosa. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice. 2013;1:224---38. the Research References 1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] (D. Vancampfort). ∗ 14 January 2014; 14 January 2014