* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Sample Chapter 3

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

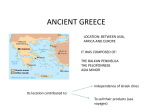

Regions of ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of Greece and the Greek world wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup