* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Urban Forestry and Climate Change Workshop

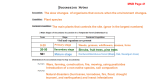

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climatic Research Unit documents wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Urban heat island wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on Australia wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Climate change, industry and society wikipedia , lookup

Mountain pine beetle wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup