* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Year of the Four Emperors

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

The Last Legion wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Late Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

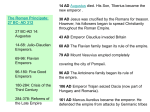

CALIGULA (AD 37-41) Gaius was born on 31 August, A.D. 12, probably at the JulioClaudian resort of Antium (modern Anzio), the third of six children born to Augustus's adopted grandson, Germanicus, and Augustus's granddaughter, Agrippina. As a baby he accompanied his parents on military campaigns in the north and was shown to the troops wearing a miniature soldier's outfit, including the hob-nailed sandal called caliga, whence the nickname by which posterity remembers him. His childhood was not a happy one, spent amid an atmosphere of paranoia, suspicion, and murder. Instability within the Julio-Claudian house, generated by uncertainty over the succession, led to a series of personal tragedies. When his father died under suspicious circumstances on 10 October A.D. 19, relations between his mother and his grand-uncle, the emperor Tiberius, deteriorated irretrievably, and the adolescent Gaius was sent to live first with his great-grandmother Livia in A.D. 27 and then, following Livia's death two years later, with his grandmother Antonia. In the interim, his two brothers and his mother suffered demotion and, eventually, violent death. Throughout these years, the only position of administrative responsibility Gaius held was an honorary quaestorship in A.D. 33 When Tiberius died on 16 March A.D. 37, Gaius was in a perfect position to assume power, despite the obstacle of Tiberius's will, which named him and his cousin Tiberius Gemellus joint heirs. (Gemellus's life was shortened considerably by this bequest, since Gaius ordered him killed within a matter of months.) Backed by the Praetorian Prefect Q. Sutorius Macro, Gaius asserted his dominance. He had Tiberius's will declared null and void on grounds of insanity, accepted the powers of the Principate as conferred by the Senate, and entered Rome on 28 March amid scenes of wild rejoicing. His first acts were generous in spirit: he paid Tiberius's bequests and gave a cash bonus to the Praetorian Guard, the first recorded donativum to troops in imperial history. Finally, he recalled exiles and reimbursed those wronged by the imperial tax system. His popularity was immense. Yet within four years he lay in a bloody heap in a palace corridor, murdered by officers of the very guard entrusted to protect him. What went wrong? Gaius’ (Caligula’s) "Madness" The ancient sources are practically unanimous as to the cause of Gaius's downfall: he was insane. The writers differ as to how this condition came about, but all agree that after his good start Gaius began to behave in an openly autocratic manner, even a crazed one. Outlandish stories cluster about the raving emperor, illustrating his excessive cruelty, immoral sexual escapades, or disrespect toward tradition and the Senate. The sources describe his incestuous relations with his sisters, laughable military campaigns in the north, the building of a pontoon bridge across the Bay at Baiae, and the plan to make his horse a consul. Modern scholars have pored over these incidents and come up with a variety of explanations: Gaius suffered from an illness; he was misunderstood; he was corrupted by power; or, accepting the ancient evidence, they conclude that he was mad The best explanation both for Gaius's behavior and the subsequent hostility of the sources is that he was an inexperienced young man thrust into a position of unlimited power, the true nature of which had been carefully disguised by its founder, Augustus. Gaius, however, saw through the disguise and began to act accordingly. This, coupled with his troubled upbringing and almost complete lack of tact led to behavior that struck his contemporaries as extreme, even insane. Conspiracy and Assassination The conspiracy that ended Gaius's life was hatched among the officers of the Praetorian Guard, apparently for purely personal reasons. It appears also to have had the support of some senators and an imperial freedman. As with conspiracies in general, there are suspicions that the plot was more broad-based than the sources intimate, and it may even have enjoyed the support of the next emperor Claudius, but these propositions are not provable on available evidence. On 24 January A.D. 41 the praetorian tribune Cassius Chaerea and other guardsmen caught Gaius alone in a secluded palace corridor and cut him down. He was 28 years old and had ruled three years and ten months. NERO (AD 54-68) The death of Claudius in 54 A.D., generally thought to have been planned and carried out by his wife Agrippina Minor, secured for her son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus the place as emperor which she had so carefully arranged. Before his death, Claudius, though he already had a son Britannicus, had adopted Lucius, who changed his name to Nero Claudius Caesar, (a great-great-grandson of Augustus) at Agrippina's instigation. Since Nero was only an adolescent, the early part of his reign was characterized by direction from these older figures, including Agrippina herself. Some scholars see a struggle between Agrippina and others for control of the young emperor, and when Agrippina began to show favor to Britannicus, a legitimate (though slightly younger) heir and possible rival, Britannicus' murder was arranged (55 A.D.) and Agrippina's authority displaced. The next year Agrippina herself was murdered, with Nero's knowledge. Nero's Marriage and the Burning of Rome Nero divorced, exiled and eventually had his first wife murdered to make room for Poppaea who he married in 62 A.D. She bore a daughter to him the next year, but the child died only a few months later. The events of 62 and the next few years did little to improve public perception of Nero. In 62, at a counselor’s urging, a series of treason laws were put to deadly use against anyone considered a threat. In 64 A.D. a great fire left much of the city in ruins. He is often depicted as playing the fiddle while Rome burned, but this has never been proven. Nevertheless, rumor has it that Nero himself ordered the fires set to make room for a building project which was begun right after the fire. Nero's Fall From Power His enemies had become numerous, and that same year a plot to assassinate Nero and to replace him with Gaius Calpurnius Piso was both formulated and betrayed; many influential Romans were forced to commit suicide for taking part in the assassination plot. In his paranoia after the conspiracy he ordered a popular and successful general, Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, to commit suicide, a decision which left other provincial leaders in doubt about his next move and inclined toward rebellion rather than inaction. The Year of the Four Emperors In 68 A.D. Vindex revolted in Lugdunensis, as did Clodius Macer in Africa. Galba declared his allegiance to the Senate and the Roman people, rather than to Nero. Such unrest in the provinces, coupled with intrigue at Rome among the praetorians (orchestrated at least in part by Nymphidius), provided Nero's enemies, especially within the Senate, with their chance to depose him. He committed suicide on 9 June 68 A.D. TRAJAN (AD 98-117) Early Years through the Dacian Wars Born into a poor noble family, Trajan earned his respect by serving in the military during a number of key campaigns in Judea, Germany, and Greece. His success in the military was awarded with several high positions including governor and consul of several provinces. He was governor of a German province when he received news that he was now the adopted heir to the emperor, but remained there to take care of some rebellious Germans. He was able to crush these rebels and expand the empire into what is now modern day Germany. When he returned to Rome victorious, his triumph (celebration or party) lasted 123 days with free games and gladiator matches. Much of the native population which had survived warfare was killed or enslaved, their place taken by immigrants from other parts of the empire. The vast wealth of Dacian mines came to Rome as war booty, enabling Trajan to support an extensive building program almost everywhere, but above all in Italy and in Rome. In the capital, Apollodorus designed and built in the huge forum already under construction a sculpted column, precisely 100 Roman feet high, with 23 spiral bands filled with 2500 figures, which depicted, like a scroll being unwound, the history of both Dacian wars He devoted much attention and considerable state resources to the expansion of the alimentary system, which purposed to support orphans throughout Italy. Trajan certainly took advantage of that mood by improving the reliabilty of the grain supply. The plebs esteemed the emperor for the glory he had brought Rome, for the great wealth he had won which he turned to public uses, and for his personality and manner. During his reign, he expanded the Roman road system, improved Roman harbors making trade more reliable, and built a number of temples and monuments that kept the unemployed busy for years. The Parthian War In 113, Trajan began preparations for a decisive war against Parthia. He had been a "civilian" emperor for seven years, since his victory over the Dacians, and may well have yearned for a last, great military achievement, which would rival that of Alexander the Great. Yet there was a significant cause for war in the Realpolitik of Roman-Parthian relations, since the Parthians had placed a candidate of their choice upon the throne of Armenia without consultation and approval of Rome. When Trajan departed Rome for Antioch, in a leisurely tour of the eastern empire while his army was being mustered, he probably intended to destroy at last Parthia's capabilities to rival Rome's power and to reduce her to the status of a province (or provinces). It was a great enterprise, marked by initial success but ultimate disappointment and failure. In 114 he attacked the enemy through Armenia and then, over three more years, turned east and south, passing through Mesopotamia and taking Babylon and the capital of Ctesiphon. He then is said to have reached the Persian Gulf and to have lamented that he was too old to go further in Alexander's footsteps. In early 116 he received the title Parthicus. The territories, however, which had been handily won, were much more difficult to hold. Uprisings among the conquered peoples, and particularly among the Jews in Palestine and the Diaspora, caused him to gradually resign Roman rule over these newlyestablished provinces as he returned westward. The revolts were brutally suppressed. In mid 117, Trajan, now a sick man, was slowly returning to Italy, having left Hadrian in command in the east. When he died, he designated Hadrian, his 2nd in command, as his successor while on his death bed. There was no realistic rival to Hadrian, linked by blood and marriage to Trajan and now in command of the empire's largest military forces. Hadrian received notification of his designation on August 11, and that day marked his dies imperii. Among Hadrian's first acts was to give up all of Trajan's eastern conquests. HADRIAN (AD 117-138) When Trajan’s cousin died, Trajan adopted his cousin’s son, Hadrian, as his heir. Since Trajan had no children of his own, he set up Hadrian as his successor even marrying Hadrian to his niece. This marriage was not a happy one, although it endured until her death in 136 or 137. There were no children, and it was reported that Sabina performed an abortion upon herself in order not to produce another monster. In spite of marital unhappiness, the union was crucial for Hadrian, because it linked him even more closely with the emperor's family. Hadrian travelled through one province after another, visiting the various regions and cities and inspecting all the garrisons and forts. Some of these he removed to more desirable places, some he abolished, and he also established some new ones. He personally viewed and investigated absolutely everything, not merely the usual appurtenances of camps, such as weapons, engines, trenches, ramparts and palisades, but also the private affairs of every one, both of the men serving in the ranks and of the officers themselves, - their lives, their quarters and their habits, - and he reformed and corrected in many cases practices and arrangements for living that had become too luxurious. He drilled the men for every kind of battle, honouring some and reproving others, and he taught them all what should be done. And in order that they should be benefited by observing him, he everywhere led a rigorous life and either walked or rode on horseback on all occasions, never once at this period setting foot in either a chariot or a four-wheeled vehicle. He covered his head neither in hot weather nor in cold, but alike amid German snows and under scorching Egyptian suns he went about with his head bare. It was during this time that Hadrian began his lasting legacy to history—Hadrian’s Wall. The wall was built in northern Britain to keep out Scottish barbarians. Hadrian was a man of extraordinary talents, certainly one of the most gifted that Rome ever produced. He became a fine public speaker, he was a student of philosophy and other subjects, who could hold his own with the luminaries in their fields, he wrote both an autobiography and poetry, and he was a superb architect. It was in this last area that he left his greatest mark, with several of the empire's most extraordinary buildings and complexes stemming from his fertile mind. While Hadrian did do a good job reforming the provinces, he was often criticized in Rome for his absence. He left several people in Rome to run the day to day matters while he toured the empire. This infuriated the Senate who surprisingly did not try to kill him. He lived to an old age and died peacefully. Diocletian (284-305 AD) The Emperor Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus (A.D. 284-305) put an end to the disastrous phase of Roman history (235-284) where generals fought each other constantly for the imperial throne. This period of turmoil opened Rome up to invasion by northern “barbarians” like the Franks and Goths. Like other emperors before him, Diocletian made his name in the army and was eventually chosen to succeed as Caesar. As emperor, Diocletian was faced with many problems. His most immediate concerns were to bring the mutinous and increasingly barbarized Roman armies back under control and to make the frontiers once again secure from invasion. His longterm goals were to restore effective government and economic prosperity to the empire. Diocletian concluded that stern measures were necessary if these problems were to be solved. He felt that it was the responsibility of the imperial government to take whatever steps were necessary, no matter how harsh or innovative, to bring the empire back under control. During this time, Diocletian broke with the old tradition of waiting until an emperor’s death before worshipping him. He declared himself a descendent of Jupiter, required visitors to bow before him, and cut himself off from the public. Because of his harsh and cruel tactics to restore order, he was not always liked. However, he was faced with a nearly impossible situation to cope with and did an amazing job restoring order to Rome. One of the methods he used to control the entire empire was to divide it into smaller manageable empires. Since the empire stretched across the Mediterranean and Europe, he thought it was too big to be ruled by one person. He divided it into 4 areas, creating an emperor for each area. This was known as the Tetrachy or rule by four. This splitting of the Roman Empire would have far reaching consequences. Despite the fact that his first wife and daughter were reportedly Christian, Diocletian sought to restore order by forcing Christians to take part in the imperial cult or emperor worship. Christians were often tortured for failing to comply with these new laws. Unlike many Roman emperors who were killed or assassinated by those seeking power, Diocletian actually abdicated (retired) from the throne in 305 AD. He left the Roman Empire divided under the rule of four able emperors, but could never have imagined the chaos, this division would actually bring. World History I- Mr. Marsh Roman Emperor Activity Station #1- Caligula 1. How did Gaius (Caligula) become the sole emperor? 2. What did he do to appeal to the people in his first years as emperor? 3. Give some examples of Caligula’s behavior that caused people to think he was crazy. 4. Who killed him and why? Station #2- Nero 1. How did Nero become emperor? 2. Why is Nero hated so much? 3. What did he do when he discovered the plot to assassinate him? 4. Why did he commit suicide? Station #3- Trajan 1. What career did Trajan have before being named emperor? 2. How did he pay for his extensive building project? 3. Why did the commoners love Trajan? 4. Who did Trajan want to model himself after? 5. How did he die? Station #4- Hadrian 1. How was he related to Trajan? 2. Why did he marry Sabina even though they were unhappy together? 3. What did Hadrian spend much of his reign doing? 4. What was Hadrian’s lasting legacy? 5. Why was he criticized? Station #5- Diocletian 1. Why was the period before Diocletian came to the throne so troublesome? 2. What were the problems he had to figure out? 3. What strange habits did Diocletian adopt? 4. How did he decide to control the empire? 5. How did his rule end?