* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 10.1 The Spread of Islam to Asia

Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Islamism wikipedia , lookup

Salafi jihadism wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Sikhism wikipedia , lookup

War against Islam wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Muslim world wikipedia , lookup

Islamic Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

Islam and violence wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Islamic socialism wikipedia , lookup

Islam in the United Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Sudan wikipedia , lookup

Islamic missionary activity wikipedia , lookup

Schools of Islamic theology wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Reception of Islam in Early Modern Europe wikipedia , lookup

Spread of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Indonesia wikipedia , lookup

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Europe wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Hindu–Islamic relations wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

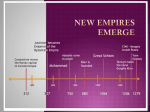

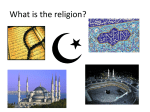

The Spread of Islam to Asia In looking at the time after the death of Muhammad it is essential to the understanding of the rapid spread of Islam to note that its adherents believed their success was the result of the truth of the Koran and the direct result of the support of Allah. The Arabs had carved out an empire that expanded both West to North Africa and Spain and East across the old Persian Empire and into Central Asia. As a result of this expansion coupled with this belief, Muslims assumed that Muhammad was a prophet for all mankind and that their empire should one day include the whole human race. From then on regions under their control were known as “the sphere of Islam” while regions beyond their control were simply called the “regions of the war.” In this article we will trace the expansion of Islam to the East. While historians argue over the motives for this expansion, with some saying it was spurred by zeal for the perfect religion and others saying it was just to acquire booty, all agree that Islam was originally spread by the sword, a process advocated in the Koran. During the ten years immediately following the death of Muhammad in 632, Arab Muslims erupted out of the Arabian Peninsula and conquered Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and western Iran. In the next decade, Arab armies marched eastward across the Iranian plateau and completed the destruction of the Sasanian dynasty that ruled Persia, killing the “King of Kings” and forcing his son to flee to the Tang court in China. By 712 Arab armies had seized strategic oasis towns in Central Asia from where they would soon meet Chinese armies face to face. To the south, Muslim navies sailed to the coasts of western India where in 711 they conquered and occupied the densely populated Hindu/Buddhist society of Sind. Thus began the long and eventful encounter between Islamic and Indic civilizations during which time Islamic culture would penetrate deep into India’s economy, political systems, and religious structure. While Arab rule in Sind was being consolidated, other Arab forces continued the overland drive eastward. Requested by Turkish tribes to intervene in conflicts with their Chinese overlords, Arab armies in 751 marched to the westernmost fringes of the Tang Empire and fought Chinese forces on the banks of the Talas River. The Arabs’ crushing victory there, one of the most important battles in the history of Central Asia, probably determined the subsequent cultural evolution of the Turkish peoples of that region, who thereafter adopted Muslim and not Chinese civilization. Although Muslims would never dominate the heartland of China or penetrate in Chinese civilization as they would India, their influence in Central Asia gave them access to the Silk Road, which for centuries to come served as a conduit for Chinese civilization into the Muslim world and beyond. These and earlier maritime contacts with China would prove to be important trading relationships. Again, a look at motives is in order. Muslims, of course, believed that the explosion of their culture from Gibraltar to the Indus River in just 130 years was a miracle of Allah’s favor contributing to their belief that the will of Allah and the historical process were synonymous. Christians, especially in India, recorded their belief that Muslims were like locusts in their berserk fondness for the “scent of war.” In obvious horror, they noted that Muslims loved “rapine” and that every Muslim warrior fought because he was promised “a damsel or two” as spoils of war. Non-religious perspectives calculated that the Arabian Peninsula had just experienced a severe drought causing Arabs to literally seek greener pastures. Other theorists said the expansion of an Islamic empire east was the natural consequence of the Byzantine Empire’s clash with the Sasanian Persians in that both of these civilizations had worn each other out in fighting. While a combination of the above factors is certainly possible, none of them can be seen without taking a careful look at the concept of jihad, or “holy war.” Verses 74 and 75 of the fourth sura, or chapter, of the Koran explain the purpose of jihad: Let those who would exchange the life of this world for the hereafter, fight for the cause of Allah; whoever fights for the cause of Allah, whether he dies or triumphs, We shall richly reward him. And how should you not fight for the cause of Allah, and for the helpless old men, women, and children who say: ‘Deliver us, Lord, from this city of wrongdoers; send forth to us a guardian from Your presence; send to us from Your presence one that will help us’? The true believers fight for the cause of Allah, but the infidels fight for the devil. Fight then against the friends of Satan. In the minds of many of the victims of Islamic expansion, and perhaps in the minds of some Muslims, jihad was the chief explanation for Arab militancy. Coupled with this explanation is the lure for potential Muslim martyrs of an Islamic paradise filled with dark-eyed beauties awaiting those faithful who died during a jihad. This interpretation of passages from the Koran may have been the fundamental uniting impulse propelling Islamic forces into battle despite disunity among various Arab tribes created by the power struggle after the death of the Prophet. Still other scholars point to the methodical manner in which these military conquests were planned and how well the plans were executed to posit that the expansion by the sword was undertaken for the entirely rational purpose of providing the growing Muslim community with support the Arabian peninsula could not provide (until the discovery of petroleum there). Lucrative trade routes and surplus-producing regions became necessary to support a centralized caliphate. Regardless of the actual motive or motives, conquest did serve as a channel for the tremendous energies unleashed by the teachings of Muhammad and the unification of formally warring Arab tribes. Even with this expansive distraction caliphs were assassinated by their own troops. Speaking of caliphs, a brief history of the political power structure of Islam as it expanded provides needed perspective. The period from the death of Muhammad in 632 to 661 is known as the Rashidun, or “rightly guided” period when the caliphs had actually been companions to the Prophet. This period was followed by the Umayyads who held power from 661-750 and, among other accomplishments, conquered Palestine and built the Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem in 691. This Dome enshrines the Rock from whence Muhammad is said to have ascended into heaven, and while literature is written about the Prophet, claims of individuals that they were also receiving revelations from Allah were silenced when Muhammad was announced to be the last Prophet. The Umayyads, incidentally, were also the Arabs who temporarily took possession of Spain and were repulsed from conquering more of Europe at the Battle of Tours in 732. The Abassid Dynasty took over from the Umayyads in 750 and by its demise in 1258 was responsible for the conquest of Persia. When the Abassids established their capital in Baghdad, however, this move off the Arabian Peninsula increased the influence of Turks, Persians, and other ethnic groups in the Muslim world. After this point the Abassids, while remaining the symbolic rulers of the empire, actually fell under the control of first a North African dynasty known as the Fatimids and then under the control of the Seljuk Turks. The Mongol invasions of which you will learn more, soon, put an end to this classical period of the rule of the caliphate. Major Muslim rulers who had achieved autonomy in outlying provinces preferred the title of sultan after the decline of the Arab caliphates. Your textbook provides the Arabic meaning of sultan, “victorious,” a title descriptive of how sultans secured and maintained their power. Subsequent sultans held regional control in a succession including the Mamluks (1250-1517), the Ottoman Turks (1412-1918), the Safavids of Persia (1500-1779), and the Mughals of India (1526-1730). Along the way to empire, Muslim conquerors brought with them Muslim scholars. A great cultural exchange occurred in Muslim centers of learning where Greek, Persian, Hindu, and even Chinese ideas were sifted and synthesized but above all preserved. Muslims made important strides in mathematics and science based on these contacts, but they also performed an important historical task in simply translating the ideas of these ancient cultures into Arabic long after Europe had lost them. When peaceful exchanges of ideas were possible, great strides in all cultures were reignited. Then the fires of mistrust and violence were reignited. The ideas got through, however, and the infusion of ancient ideas became the basis for European movements like the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution. Stay tuned for more information. Islamic mathematicians believed, like some ancients, that through numbers men could ascend beyond this world of confusion to a higher, abstract realm of eternal truths. They regarded mathematics as “the tongue which speaks of unity and transcendence” and even used some calculations based on numerical values of some of the names of God as magic charms. Building on Greek and Hindu foundations, Islamic thinkers like Omar Khayyam made important strides in algebra and geometry. Scholars working at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad wrote a book on algebra that also contributed to the development of trigonometry. We all have Arab mathematicians from medieval Spain to thank for giving us the simplicity of the numerals 1 through 9 as opposed to the more cumbersome Roman numerals. The Arabs are said to have derived their numerals from Hindu sources, but their greatest original contribution lay in their use of dots to hold empty places in columns of numbers. When calculating numbers, they represented ten with a 1 followed by a dot. One hundred was a 1 with two dots after it, and they could even represent one million and one as 1-dot-dot-dot-dot-dot-1. Arab mathematicians called the dot sifr, or “empty” from whence we get the word cipher. When Italians got a hold of a dot like this they called it a zero. In science, increased knowledge of geometry and algebra led to advances in optics and astronomy. One Arabic observer even noted in his chart of systematic observations that the quirky behavior of Venus would be much more easily explained if one viewed the planet as orbiting the sun rather than the earth, but the Ptolemaic geocentric universe was too ingrained to make that observation start a revolution in thought. These astronomical observations had practical uses for Muslims in helping them determine the direction of Mecca and to maintain a lunar calendar, but also in navigation of the Indian Ocean. Mathematics encouraged the improvement of the physics of water clocks and of irrigation systems. Arabic alchemists sought a way to create gold from lesser materials, but in the process they used distillation, evaporation, crystallization, and filtration. To do these chemical processes they needed vials, beakers, mortars and pestles, flasks, smelters, and other equipment you might have seen in your chemistry lab. I have found no reference to safety goggles, though, hence the ultimate demise of the Muslim empire. In medicine, Arabic scholars built on Hindu and Persian medical lore as well as on the writings of the Greek physician, Galen, who had summarized ancient Mediterranean medicine in the second century A. D. Muslim physicians were not bound by these texts, though, and recorded their own opinions. Among other discoveries, an Arab in 900 was the first to distinguish between smallpox and measles. Your textbook makes a critical distinction that marks a major turning point in the expansion of Islam in Asia that will also be our last focus in this lesson. The conquest of Persia and some sites in India by the sword of jihad led to trade with central and southern Asia that subsequently led to an exchange of ideas. Accompanying merchants into these frontier areas were a particular type of Muslim mystic missionaries called Sufis. Sufis were an important sect of Islam probably called such because of their simple woolen garments (sūf is the Arabic word for wool). Sufis were called mystics because they believed that through meditation and pious self-discipline they had attained a direct personal experience with Allah. Sufis sought to go beyond mere expansion and organization of a Muslim world community toward spiritual development. Unlike the image of Allah pictured in the Koran as transcendent and impersonal, Sufis believed Allah was accessible. Individual Sufi mystics attracted groups of followers who imitated their “paths,” or series of mental and physical exercises leading up to communion with Allah. Sometimes this path led to adherents’ living together in a monastic lifestyle; others traveled and taught their ideas. Some of these peripatetic leaders were said to have performed miracles and thus attracted wide, popular followings. Their burial sites became shrines visited by thousands of the faithful. Among the most widely known expressions of Sufism is that of the whirling dervishes. In their quest for spiritual exaltation, dervishes participate in meditation rituals that involved ecstatic dancing with carefully proscribed breathing techniques. Dervishes have been seen to dance until completely exhausted and then to walk on red hot coals or actually to place red hot coals in their mouths, to breathe rapidly until the goals are white hot, and to chew and swallow them—all with no outward signs of pain. One dervish order in Egypt ended their extravagant dance rituals with the leader riding a horse over the bodies of his followers who had thrown themselves in his path. Sufism became the key to successful conversions and thus successful political mastery of what became known as the Sultanate of Delhi and the later expansion into Indonesia. Muslims had opened India by conquest and opened trade to Southeast Asia from there. As mentioned earlier, the Muslim trading ships that plied the Indian Ocean also had aboard travelling Sufi holy men. The asceticism of Sufi teachers made them attractive to people used to Hindu and even Buddhist holy men, and as Muslim power grew, conversions increased. Lower-caste Indian peoples were especially interested in the teaching of Muhammad about social equality. A poem by the Sufi poet, Kabir, reveals why this might have been so. It is needless to ask of a saint the caste to which he belongs; For the priest, the warrior, the tradesman, and all the thirty-six castes, alike are seeking for Allah. It is but folly to ask what the caste of a saint may be; The barber has sought Allah, the washerwoman, and the carpenter. Even Raidas was a seeker after Allah. The Rishi Swapacha was a tanner by caste. Hindus and Moslems alike have achieved that End, where remains no mark of distinction. In what amounts to an historical irony, the later Hindu spiritual and revolutionary leader of India, Mohandas Gandhi, was still trying to achieve peace between Hindus and Muslims in India when he was assassinated in 1948. His failure to do so led to the formation of what is today Pakistan.