* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 071. Times New Roman

Ancient Roman architecture wikipedia , lookup

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Executive magistrates of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Leges regiae wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Elections in the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Rome (TV series) wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

Conflict of the Orders wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

First secessio plebis wikipedia , lookup

Roman Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

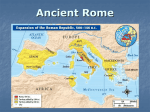

Times New Roman No recorded history of the foundation of the city of Rome exists. Romans themselves possessed traditions about their origins, however, that could possibly have some basis in fact. Many mythological explanations of ancient events contain kernels of truth, and recent archaeological evidence suggests that at least something of the story of Romulus and Remus is true. Legends say these twin brothers were abandoned in a field as infants because of maneuvering among claimants to the throne of the Latin people. Suckled by a she-wolf who had lost her own offspring, the boys survived to be discovered by a shepherd and raised on the Palatine Hill near the Tiber River on the coast of central Italy. The Latin word lupa was reportedly also used in reference to prostitutes, however, so Romulus and Remus could merely have been the sons or the adopted sons of another kind of she-wolf. Together they might have become great chieftains, but much is foreshadowed about Roman values in that the legend took a dark turn in an act of fratricide. Having consulted an oracle, the twin brothers as young men set out to fulfill their stated destiny that they would found a great city. Romulus chose the Palatine Hill as the site and began to plough out the ring marking the location of the city’s wall. Remus, who wanted to choose another site, jokingly leapt over the line for the wall and predicted his brother’s enemies would also one day leap over. Romulus killed Remus on the spot and was thus free to name the city after himself. He built a stone hut and began the wall in 753 B. C., the traditional founding date for Rome. Archaeologists have lent verisimilitude to the story because they have now found the hut and the wall’s foundation. Outcasts and criminals were drawn to the new city, but none of these were women. The enterprising Romulus led his band of brigands in a raid on a neighboring city-state and abducted the Sabine women. When the Sabine men followed to rescue their wives and daughters it is said the women themselves stopped the violence by standing between the opposing forces and agreeing to go with the Romans. Thus the population of Rome began to grow even though to fratricide was added rape among the Roman original sins. An original Roman value was instilled through these events either real or mythical—one can take whatever he can keep. The Latin people who flocked to Rome were ruled by six kings after the death of Romulus while Rome was a thriving city-state or kingdom. Three of these kings were Etruscans, including the sixth, who was overthrown and whose demise marks the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 B. C. The most important accomplishments of the Kingdom of Rome were the unifying of the Italian peninsula under the Roman monarch and the keeping of peace between patricians (those who could trace their lineage back to a Sabine woman) and the plebeians (commoners). Their doing so marks the launch by Romans of the Hellenistic ideal of a world culture. As the first practical success in this regard, Rome was eventually responsible for visionary accomplishments in law and government. The “glory that was Greece” lay in architecture and philosophy; the “grandeur that was Rome” borrowed these, modified them, and added their own genius of assimilation of foreigners into a governmental structure based on a code of laws. The overthrow of the last King of Rome, and thus the achieving of independence of the Latin people from the Etruscans, was the doing of the patricians who by then were the landowning aristocrats. Patricians naturally thought of themselves as the most important citizens of Rome for this feat but also because of their wealth and power. They reserved certain sacred duties in Roman religion to themselves alone. They saw themselves as preservers of sacred traditions. Patricians owned most of the land, held most of the power in the Senate (an assembly founded by none other than Romulus), and controlled the Roman army. This last institution consisted of plebeians who were the main foot soldiers directed by aristocratic nobles who were the officers. Fresh from consolidating most of Italy under Roman rule, these armies were the most formidable in the Mediterranean World. Roman soldiers could march 30 miles per day with a pack of weapons and other gear weighing 60 pounds. You try that sometime! Control of Rome required control of the army. The executive heads of state were two annually elected men called consuls who each could veto the action of the other. Exceptions to this arrangement came in times of great crisis when absolute power for six months at a time was placed into the hands of a dictator nominated by the consuls and voted on by the Senate. The Senate was the main source of patrician power although it did not legislate as does ours, but it did control public finances, the appointment of lesser officials below the consuls, and foreign policy. The plebeians, on the other hand, chafed under such grievances as enslavement for debt, discrimination in the courts, prevention of marriage with patricians (and thus political and social advancement), lack of representation in the government, and the absence of a written code of laws. The plebeians sought change by threatening to go “on strike.” The patricians realized just how much this word hurt Rome when they saw that without plebeian taxes and soldiers Rome would collapse. The plebeians were granted their own Plebeian Assembly, later known as the Tribal Assembly. This Assembly could elect officers called tribunes to look after the affairs of the commoners over against the affairs of state. Ultimately a law code called the Twelve Tables was written down with the intention of protecting the Plebeians. Stay tuned for more analysis of this Roman legacy, later. Also, don’t overlook the reality that the patrician nobility sought and found ways to maintain their grip on power. As Rome expanded so much as to burst beyond their peninsula, remember the rugged Roman soldiers who combined personal valor with the Greek notion of fighting as units in formation. Soldiers, and thus phalanxes, were told, “Yield you not to ill fortune, but go against it with more daring.” Romans willingly made sacrifices to seek the expansion of the Republic and eventually of the Empire. Still, despite the shadiness of its origins, Rome proved to be a benevolent master. Instead of practicing the ancient custom of enslaving conquered peoples, defeated communities were allowed to retain a measure of self-government. Rome deliberately endeavored to gain the loyalty of conquered peoples through generous treatment. Rome thus displayed a talent for converting formers enemies to its own way of life and some into Roman citizens.