* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PDF

Psychedelic therapy wikipedia , lookup

Separation anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry in Russia wikipedia , lookup

History of psychosurgery in the United Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Anti-psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Critical Psychiatry Network wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar II disorder wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Causes of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Death of Dan Markingson wikipedia , lookup

Generalized anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Biology of depression wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric hospital wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

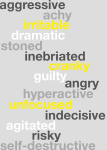

Hopkins THE NEWSLETTER Winter 2008 O F T H E J O H N S H O P K I N S D E PA R T M E N T O F P S Y C H I AT RY A N D B E H AV I O R A L S C I E N C E S VO L U M E 4 , N U M B E R 2 T R A N S L AT I O N S Adding Insult to Burn Injury Model of a Muddle “It’s like you’re in a phone booth late at night in a bad neighborhood. You don’t know how to get home. The floor’s littered with cigarette butts. It’s hard to see out the filthy windows but no one out there would help you anyway. A voice on the receiver tells you you’re in danger.” That’s one patient’s description of post-trauma distress. But if you’re a burn survivor and have slipped further, into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), there’s a street gang with a snarling mastiff outside the booth. And you know they’re not going away. T he physical results of severe burns are well-documented, says psychologist James Fauerbach, Ph.D., who sees roughly 400 seriously burned adult patients at Hopkins Bayview’s burn center each year. But the mental aspects—the potential anxiety disorders, altered body image, the downswing in mood that social stigma and isolation, chronic pain, itching and insomnia can bring—are less well understood. And Fauerbach and his colleagues are remedying that. Ironically, their studies are crucial because new approaches to wound care and more effective rehab have cut hospital stays for survivors by more than half. “So it’s imperative that we identify patients at risk for problems after discharge,” says Fauerbach. Burn survivors are especially prone to PTSD and other anxiety disorders. Roughly a third of those severely burned George Abucevicz, who was burned when an electric panel exploded, “has the hallmarks of psychological resilience that bode well for his recovery,” says Jim Fauerbach. “He sees the good in these most trying circumstances.” meet PTSD criteria the year after injury: they show the classic symptom clusters of intrusive distressing thoughts of the traumatic event, suppression of anything that calls it to mind and hyperarousal, with its insomnia, anxiety and irritability. For the past decade, Fauerbach—head psychologist for the burn unit—and his team have run defining studies on survivors’ mental health, both immediate and long term. They’ve shown, for example, that patients with previous psychiatric disease do less well long term after their injury. And those who develop PTSD while hospitalized find the disorder harder to shake after discharge. They’ve also examined the anxiety process. “The immediate reaction to burn trauma is usually shock and helpless- ness,” says Fauerbach. How could that be otherwise? Pain is excruciating. Patients might see their skin hanging in sheets or see others react to their appearance with horror. In the next days, they begin to replay what happened, to have nightmares or intrusive memories or flashbacks, even. All are unpleasant; all reopen the initial event. “What’s especially unsettling,” he adds, “is that these thoughts and feelings come automatically, without the patient willing them to occur. That can be part of the healing process. However, in many, a kind of cycling takes place. As thoughts intrude, patients try to suppress them to manage the anxiety. And this bouncing back and forth between intrusions and avoidance—this way of coping, we’ve found—seems to get Withdrawal Is Withdrawal The Incredible Shrinking Brain Marijuana, too, can be hard to kick. Chronic, untreated depression could change the brain. PAGE 2 PAGE 3 people stuck. They’re most likely to develop acute anxiety and PTSD problems.” Help, however, appears to come from an unusually close overlap of psychology and psychiatry. Fauerbach’s psychology-based team works closely with psychiatric specialists in anxiety disorders led by Una McCann, M.D. They integrate use of medications with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that Fauerbach’s tailored to burn survivors. "We help them evaluate thinking that undermines confidence, that interferes with recovery,” he says. His five-year study of the specialized CBT—it encourages resilience and empowerment—has just begun. “It should clarify what’s protective, what’s therapeutic.” ■ E-mail [email protected] for information. More Than Spare Parts Transplant’s resident psychologist aims for the doable. PAGE 4 Psychiatrist Una McCann is deeply interested in post-traumatic stress disorder because treatment for the vile, often lasting condition isn’t foolproof. But, as a neuroscientist, McCann sees PTSD in rather a different light: Not only is she eager to map out its biology, but she believes it could prove useful to understand the workings of one of its most helpful treatments—cognitive behavioral therapy—and thus put the technique to best use. McCann, who heads Hopkins’ Anxiety Disorders Clinic, has nudged cognitive therapy’s status in the clinic upward, combining it more routinely with medications. “Both,” she says, “are empirically proven for anxiety disorders.” She’s brought in psychologist James Fauerbach (story, left), who’s sharpened his CBT expertise from years of working with burn patients at Hopkins Bayview. Fauerbach now trains all of Psychiatry’s residents in the technique. “PTSD is almost the perfect model for the behavioral medicine approach to psychiatric problems,” McCann explains, especially, she says, as it affects the burn survivors she and Fauerbach treat. “There’s a definite event—the burn trauma—with a before and an after. So you can follow patients and see who had a preexisting problem, see who develops an anxiety disorder, see who responds to which nuance of therapy.” Soon, she hopes, PET, fMRI and other forms of imaging will bring hard data on these patients. But questions about PTSD itself linger. Studies suggest that two brain areas concerned with emotion, the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex, respond abnormally to stimuli seen as threats. Other data hint that the hippocampus, a memory-linked area, may change size in chronic patients. “We’d like to identify brain markers for people at risk of the disorder and, ideally, use targeted therapies—including cognitive ones—before PTSD sets in,” McCann explains. Clarifying the biology will be especially satisfying, McCann says, because controversy dogs PTSD. “Even within Hopkins ranks, some psychiatrists see it as a natural response to trauma or, in some instances, evidence of a personality vulnerability. Science is a perfect way to get to the heart of the matter.” ■ For information: 410-550-2596. Coercing With Compassion A gaunt Darice Caine*, 41, came to Hopkins’ Eating Disorders Program weighed down by nearly three decades of anorexia nervosa. She’d been hospitalized at least 22 times at four different inpatient programs and a state psychiatric hospital, among others. Weighing 60 pounds, Caine was in grave danger. She carried the wounds of her illness: osteoporosis, sluggish heart rate, bruised, thinning skin, teeth eroded from vomiting. And she sat in admissions, telling director Angela Guarda, M.D., “I really don’t need to be here.” Denying illness and ambivalence toward treatment, Guarda says, are hallmarks of anorexia. Most people with AN, in fact, never seek specialized treatment. It’s in the nature of eating disorders—in line with substance abuse or sexual disorders—to promote personal sabotage. The drive to continue starving stems from the gut feeling—Guarda uses the word egosyntonic—that it’s the right thing to do. “You could say these are diseases of self-deception,” she says. And that self-deception’s severe, given that more patients die from anorexia nervosa than from From a patient letter to Angela Guarda any other major psychiatric illness—as high as 10 percent over 10 years. So Guarda became interested in seeing how necessary being motivated for treatment is to recovery. She also wanted to see if patients pressured into treat- ment change their feelings and accept the need for it later on. Her study, recently published, hinges on the fact that coercion figures into most admissions to an eating disorders inpatient program. It can be pressure from family, friends, bosses, therapists. Or, occasionally, if the situation’s life-threatening, there’s involuntary admission—a court-based process to protect psychiatric patients in immediate danger. Caine’s father, for example, brought her to Hopkins under an ultimatum: Go or you can’t live at home. She signed herself in only after hearing that her severe condition warranted her being involuntarily admitted if she refused. “Pressuring patients into treatment is very controversial,” Guarda explains. “It’s widely held that they have to feel ‘ready’ for treatment in order to benefit.” Or the idea’s there that if you pressure patients, they’re somehow harmed. “But we don’t see that,” says Guarda. Patients do come reluctantly and I-don’t-need-tobe-here is the rule, she says. “They typically lack insight.” Within a week, however, “once they’ve engaged with their peers and formed an alliance with our clinical team, we often hear, ‘I know I need this.’” They gain weight and learn to eat more normally. That’s the trend her research supports. In the study, Guarda’s team asked 139 teen-toadult patients with eating disorders to complete a modified version of the MacArthur Inventory—a tool given psychiatric patients to measure perceived coercion—when first admitted and again two weeks later. Nearly half of patients who denied needing treatment had “converted” in the two weeks, with more adults switching over. Now the team’s collecting data on a larger group for a longer time period.. “All this suggests that judicious, thoughtful persuasion and leverage can be valuable and may be necessary to help people with eating disorders,” says Guarda. As for Caine, who’s now become a nurse, her letter (left) says it best. ■ * Not her real name. For information, call 410-955-6115. “The number of people going to clinics for marijuana addiction has doubled in a decade,” says Vandrey. “And the distress they undergo in withdrawal is significant.” A Double Take on Withdrawal A side-by-side look at marijuana and nicotine withdrawal underscores the need to consider both in the clinic. Myths about marijuana use are plentiful and hard to squelch: It’s an innocuous, friendly little drug; it isn’t addictive and is easy for any user to quit; there’s little interplay between it and other illicit drug use. Such ideas have likely been around as long as the drug itself, perhaps, in part, because hard research has been relatively scarce. But in the past decade, a small cluster of scientists has made marijuana studies a specialty, describing use of the drug and the range of its effects and, more recently, pinning it down as an addictive substance with a genuine withdrawal syndrome. One of the group, Hopkins behavioral pharmacologist Ryan Vandrey, Ph.D., began marijuana research as a graduate student at the University of Vermont, home of some early definitive work. As the evidence mounts, he and colleagues are hoping to change perceptions of marijuana as harmless for everyone. “Recent research suggests as many as one in 10 who try the drug develop problems tied either to its use or to quitting it,” he says. “We need better ways to treat those seeking help.” Vandrey’s latest work, reported in the January issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence, aims to extend his earlier research on marijuana withdrawal by comparing it to that of a drug already well understood in the lab and by the man in the street—nicotine. “Ultimately, we hope to clarify withdrawal’s role in the subset of teen and adult users who find abstinence so difficult,” says Vandrey. “If it turns out to be clinically important—as our results suggest—we’ll have a therapeutic target.” Marijuana withdrawal is marked by increased anger and aggression, anxiety, depressed mood, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, strange dreams and decreased appetite. Less commonly, there are headaches, physical tension, sweating, stomach pain and general malaise. “The typical effects are probably the ones most related to relapse in patients,” says Vandrey. They’re common, he adds, to all drugs of abuse. In the new study, Vandrey and colleagues recruited heavy users of tobacco and marijua- na. Each followed a schedule that involved usual use alternating with periods of “cold turkey” abstinence from either drug as well as both at the same time. All filled out daily surveys of marijuana withdrawal and nicotine withdrawal. “Our earlier studies on withdrawal in marijuana smokers and withdrawal in tobacco smokers showed that what they go through is fairly similar,” says Vandrey. Because comparing different people introduces an element of apples versus oranges, however, the new study’s look at same-person withdrawals of both substances is stronger scientifically. It also sheds light on simultaneous withdrawal—the first such study of its kind. “This is important,” Vandrey says, “because roughly half of heavy marijuana users are also tobacco addicted. And among heavy smokers, about 9 percent have a daily marijuana habit.” In the end, withdrawal appeared similar in intensity and quality from all the angles in the study. Data from quitting both marijuana and nicotine reflect an odd turn, though: Half of participants reported it was easier to quit both substances at once; the others found it harder. While that needs looking into, Vandrey says, it at least suggests drug treatment programs should address clients’ simultaneous tobacco use, something rarely done today. ■ For information: 410-550-4036. INSIGHTS: JAMES POTASH Shrinkage, Not the Shrinks “Intriguing” is how Potash describes work that adds to depression’s hottest hypothesis. “Those who call psychiatrists head shrinkers have it wrong,” says psychiatric geneticist James Potash, M.D. In a recent departmental Grand Rounds, Potash described new evidence for an idea he finds intriguing: that chronic depression—and not clinicians— whittles the volume of specific brain areas, notably the hippocampus. It’s certainly plausible, he says, given known ties between depression, stress and the ample science that shows stress hormones can shrink that brain site. The idea of basing therapy on reversing the shrinkage of an area devoted to memory and emotion, he adds, is equally intriguing. While Potash is by no means the first to relate depression, stress and hippocampal change, his take on a possible mechanism is new. In his talk, he cited recent results from GenRED I, a large, nationwide genetics-of-depression study: A gene appeared whose workings may fit the hippocampal hypothesis like the proverbial glass slipper. In past work, Potash has found probable psychosis genes, those common to psychosis in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Currently, he’s one of a handful of psychiatrists nationwide studying epigenetic phenomena— unconventional ways of controlling conventional gene expression. Epigenetics may explain how environmental cues like day length, for example, might affect patients with mood disorders. As director of research for Hopkins’ Mood Disorders Center, Potash has helped conduct large studies to link the risk of those illnesses with specific chromosomal areas. Now he hopes to identify culprit genes via gene chip assays of thousands of patients and their family members. You’re focusing on the hippocampus in depression? Yes. Imaging studies show that the frontal cortex—which we know behaves differently in depression—is connected with deeper limbic regions, especially the hippocampus. Is there evidence it shrinks in depressed people? More than 20 studies suggest the hippocampus is smaller in patients with major depression than in those without illness, about 10 percent, on average. Some work says it’s not just depression but how long depression’s untreated that correlates with brain loss. How do you know that depressed people aren’t born with smaller hippocampi? We don’t. And there’s some evidence that hippocampal volume can be inherited. One monkey study showed it’s 54 percent heritable. On the other hand, we know definitively that the hippocampus is a brain area that makes new neurons throughout life. And that ability can vary. It decreases with age, for example. So you’re leaning toward shrinkage. What does it? Stress. Stress sets off a cascade of steroid hormones that likely alters the hippocampus. The hormones also appear to retard its new growth. So the hypothesis ... ... is that stress encourages depression. Brain and endocrine sites for our response to stress— circuitry called the HPA axis—become overactive in depression. And while the subsequent wash of steroid hormones doesn’t destroy hippocampal neurons, it likely prunes them back, changing their activity in brain circuits and perhaps producing symptoms of depression. Or maybe it’s the hormones’ slowing new growth that’s the cause. Perhaps it’s both! Can depression therapy restore the hippocampus? In animal models it can, both with antidepressants and with electroconvulsive therapy. The few studies in people suggest that too, though evidence is less clear. nine genes in that vicinity that we analyzed, one, NTRK3, piqued our interest. It codes for receptors for a natural agent—a neurotrophin—that encourages nerve cell growth in the brain. What’s next? How? Nobody knows. Perhaps it’s by reducing stress. Or it could, we believe, affect the hippocampal neuron factory. Recently, from our genetic studies on families with major depressive disorder, we’ve marked a narrow area on chromosome 15 as having some tie to depression. Of We’ve just launched a study about 2,000 times more powerful than the last to make the suspect genes far more obvious, one that should clarify what NTRK3 and others are doing. For the first time, we have the potential to understand the truth about what sets depression in motion. ■ SUPPORTING THE CAUSE For Her, Stigma’s Just a Word You look at Joan Denny’s delicate, gold-flecked scarf. Her perfume tugs at your subconscious as she leans forward; you listen as she tells of a rich and full life—despite high odds for the opposite—and it seems that even the leaves outside her picture window have arranged their color scheme at her bidding. Denny exudes stability and capability. Bipolar disorder (BP) doesn’t come to mind. But Denny, long a supporter of Hopkins’ annual mood disorders symposium, is quick to own up to her illness and explain how it’s driven her efforts to improve Psychiatry’s outlook. She’s helped the symposium for all of the 22 years it’s existed. And her willingness to talk about having bipolar illness—she does so to a degree unusual even in this day and age— advances the cause. “Mental illness has been a part of my life since birth, probably in utero, even,” she says. “I don’t ever remember a time without it.” That doesn’t mean Denny suffered it gladly. “The last thing I wanted when I was 18 was to admit I had a problem.” And as a theater major in college, she says, she learned to disguise BP to an extent. “But I couldn’t hide it when I was married. You couldn’t do that with five children under the age of 7, when you were in and out of treatment,” she explains. “They all knew what their mother was going through.” So it’s far easier, she says, to be honest about her disorder. She’s been equally forthcoming with good works. In addition to the symposium, Denny co-led a church-based volunteer peer support group. Her experience as a model patient, submitting to interviews, helps Hopkins psychiatrist Philip Slavney and others evaluate professionals for board certification. “It’s great fun. Other than interpreting ‘A rolling stone gathers no moss,’ I’ll answer about anything I’m asked.” “This illness ruined my life in many ways,” says Denny. “But if you can give back in some manner—of yourself or with money—it helps. It really does bring joy.” ■ Want to Help Us Help You? If you’re thinking of participating in a research study, visit www.hopkinsmedicine. org/psychiatry/research/ volunteers and click Research Volunteers Needed to read about studies currently recruiting participants. Hopkins needs healthy volunteers as well as those diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. More Than Spare Parts Patients going through Hopkins’ transplant service for a new heart, lung, liver or kidney are, by definition, gravely ill. So it’s natural that many are demoralized by their physical weakness and shocked at the possibility of having to sit out life’s dance. There’s the anxiety of finding a donor or facing high-risk surgery or the uncertainties of life on mega-medication. Distress can shade into depression or anxiety disorders, especially in patients already cognitively compromised from low oxygen or other effects of their illnesses. Helping patients with life adjustment problems and referring those with major depression or anxiety are clearly part of David Edwin’s work. As psychologist for Hopkins hospital’s transplant service, he also screens potential donors and recipients. “I’m not here to winnow people out so much as to make it safer to transplant them,” he says. But transplant’s no typical event, and the issues and pressures these patients face make what Edwin encounters far from predictable. “Transplants don’t occur in a vacuum,” he says. “Life in all its variety encroaches.” It’s only the discipline of what he calls “a psychological imagination” that helps him sift through layers of patient problems using the perspectives of his field. For example: The medical work-up stalled for a man awaiting a heart transplant when he ■ “When I started this 20 years ago,” says Edwin, “I thought, they’ll need a psychiatrist. But my friends in medicine and transplant surgery were generous with their teaching, my colleagues in psychiatry unfailingly supportive.” Hopkins This issue of Hopkins BrainWise is published by Johns Hopkins Medicine Marketing and Communications for the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. It is distributed to the scientific community, sponsors, friends and others interested in the department’s research and activities. SAVE THE DATE! This year's 22nd Annual Mood Disorders Symposium has Mood Disorders in Women and Adolescents as its focus. Olympic skater Dorothy Hamill and actress Mariette Hartley are featured. Tuesday, April 15, 1-6 p.m. at Hopkins' Turner Auditorium. Call 443-287-3480 for information. Some of the research in this newsletter has corporate ties. For full disclosure information, call the Office of Policy Coordination at 410-223-1608. J. Raymond DePaulo, Jr., M.D. © The Johns Hopkins University 2008 Chief of Psychiatry To make a gift to the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, contact Jessica Lunken, Director of Development Department of Psychiatry 100 North Charles Street, Suite 410 Baltimore, MD 21201 410-516-6251 If you no longer wish to receive this newsletter, please e-mail [email protected] Patrick Gilbert, Director of Editorial Services Marjorie Centofanti, Editor/Writer Dalal Haldeman, Vice President, Marketing and Communications David Dilworth, Designer Keith Weller, Photography Editorial Office 901 South Bond Street, Suite 550 Baltimore, MD 21231 couldn’t make clinic appointments. Earlier, he’d had a defibrillator implanted and its firings became terrifying. He found himself unable to undergo pre-transplant dental work because he feared the device would fire while he sat in the chair, and his anxiety generalized to the point that he rarely left home. “The agoraphobia-like syndrome behind his “noncompliance” isn’t uncommon in defibrillator patients,” Edwin explains,“but, for him, it was life threatening.” Colleagues at Hopkins Community Psychiatry stepped in and he’s now in treatment with a psychiatrist and behavior therapist. ■ A Chicago woman flew to Hopkins to be considered for an incompatible-donor transplant after her kidneys deteriorated from complications of lithium therapy. Her home psychiatrist had diagnosed bipolar disorder and the woman had a history of becoming psychotic on the prednisone normally given transplant patients. “I didn’t see the patient at her evaluation visit,” says Edwin, but records suggested more than bipolar illness. The discharge notes I requested from her previous psychiatric hospitalization described a schizoaffective disorder, which makes her a more worrisome transplant candidate. But if she had appendicitis, we’d operate for that, wouldn’t we? The question is, Is a transplant doable for her? If we don’t advocate for mentally ill people, who will? “The transplant team was concerned about steroid psychosis—many medications post-transplant aren’t benign in patients with mental illness. And while we knew we could address any acute postop problems here, we found we also had to organize adequate psychiatric care for her at home. In this case, our patient has done well.” A man with alcoholic liver disease from years of abuse was dropped from the waiting list after a weekend binge brought him to the hospital. He went “clean” for the six months required to get relisted, but admitted that he still smoked marijuana. ■ “It’s not unusual for patients to dive off the transplant list because they can’t stay abstinent,” says Edwin. “Substance disorders are a chronic part of life on the service.” Relapsing post-transplant is difficult to predict, however, and a number of patients resume some level of drinking. But marijuana drastically increases relapse risk in recovering addicts, he explains,”so we’ve become active in testing for it. We look at this not as something to rule people out permanently but as part of planning their care.” ■ Stealth Mental Health “I had no interest in psychology until I worked at Bloomingdale’s.” That’s an unorthodox but telling start to Jacquelyn Duval-Harvey’s career—first as an on-site clinician for East Baltimore school children, then as head administrator for the same Hopkinslinked mental health programs that include the schools. It’s telling because well before her clinical psychology studies in college, Duval-Harvey learned how effective mental health care could be outside the traditional clinic. Working at Bloomie’s, she observed women of a certain age who “kept coming back. They’d buy and return, day after day, until it dawned on me that this was loneliness.” Duval-Harvey’s attention to the ladies made the store somehow therapeutic. After doctoral work at Penn State and a job heading children’s programs in a New York City hospital, she came to Hopkins, where, for the first of her decade here, she was a school-based clinician. Embedded in an elementary school, Duval-Harvey became a keen advocate for mental health services in that setting. “There’s no stigma in getting psychological or psychiatric help in a school,” she says. “It’s not a place people are automatically identified as mentally ill. Also, you learn faster about issues children have—watching them in the classroom and the cafeteria can tell you if they’re socially and emotionally adjusted. Most of all, you’re in a position to intervene where it’s most critical. Success in school turns these kids’ lives around.” Duval-Harvey became head of the East Baltimore umbrella program, Community-Based Services, part of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. A liaison between the Hopkins effort and the city, state and federal bodies that target kids at risk, she refined ways to extend the school clinicians’ reach. In addition to one-on-one therapy, they also do preventive work—offering schoolwide behavior management or leading small, tailored groups that take on topics like anger management or coping with addicted, parents. “The schools work is intense; You know pretty fast if you want to keep doing it. I had no doubt.” ■ Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Permit No. 5415 Baltimore, MD