* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Augustus - Scarsdale Schools

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Julius Caesar (play) wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman emperor wikipedia , lookup

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman Republican governors of Gaul wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Illyricum (Roman province) wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Augustus

From ABC-CLIO's World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras website

http://ancienthistory.abc-clio.com/

Caesar Augustus rose from near obscurity to become the most powerful man Rome had ever

seen, and he became perhaps the single most important figure in Rome's long history. As

Rome's first emperor, he oversaw the final demise of the Roman Republic and instituted the

system of rule known as the Principate, a particularly delicate balancing act that depended as

much on Augustus' own political genius and magnetic personality as it did on his raw power—

each unmatched in Roman history.

Little is known of his childhood. Born in 63 BCE to a father who was a novus homo, or the first

family member to become a senator, Gaius Octavius was a grandnephew to Julius Caesar,

whom he accompanied on some military ventures. In spring of 44 BCE, Octavius was studying

in Dalmatia when word of the assassination of Caesar arrived. Hurrying back to Rome, he

learned that, in Caesar's publicly read will, he had been adopted by Caesar and had become

his heir. At that point, Octavius' relatives grew frightened for his safety and worried that the

conspirators who had assassinated Caesar would kill Octavius as well. In any case, Octavius

hurriedly moved through southern Italy seeking the support of Caesar's veterans.

Octavius now took the name Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, or Octavian for short, to

emphasize his relationship with Caesar. That move seems to have been calculated to make the

most of the still very powerful ties between Caesar's retired troops and their murdered former

leader. It worked. He arrived at Rome in charge of a private army that may have numbered as

many as 10,000 men.

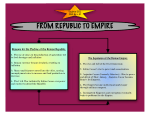

That newfound support set Octavian at odds with Mark Antony, Caesar's close ally and head

of the Caesarian party bent on punishing the followers of Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius

Cassius Longinus, the leaders of the conspiracy that resulted in Caesar's assassination. After

a period of tension, Antony and Octavian reconciled, set about destroying the forces of the

anti-Caesarian faction, and then purged their supporters at Rome and elsewhere through a

series of bloody proscriptions. The alliance between Antony and Octavian could not last,

however; after the defeat of the conspirators, Octavian set about building a base of support for

himself among the Romans, anticipating the confrontation with Antony that he knew would

come.

Octavian now began to establish himself in the eyes of his countryman as a source of stability

and restored order. Moreover, he associated himself with traditional Roman values and began

to depict his enemies as lawless, foreign, and corrupt. Meanwhile, Octavian began to court

important constituencies at Rome, including the urban proletariat, and granted himself

increasing measures of official and unofficial power.

Finally, Octavian began to agitate openly against Antony, whose involvement with the

Macedonian-Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII Thea Philopator Octavian denounced as decadently

"oriental" and un-Roman. Soon Octavian and Antony engaged in open hostilities. The decisive

Battle of Actium took place in 31 BCE; Antony and Cleopatra's combined forced were narrowly

defeated, and the next year Alexandria was taken by Octavian's forces.

Octavian was now the sole ruler of the Roman world, but he faced a new problem. How could

he avoid the fate of his uncle and adoptive father? He now occupied a similar position to that

enjoyed by Caesar just before his assassination; the undisputed victor in a round of civil war,

he now had no rival in Roman society but began to look perilously like a king, a reviled figure

in Roman political philosophy. How could Octavian maintain his position in Roman society

while avoiding assassination attempts and incessant revolts among his subjects?

The answer devised by Octavian was to articulate his position in Roman society in very

republican-sounding terms. He wanted to present his place in the Roman political hierarchy

as traditional, albeit unprecedented. It was a delicate balancing act; between 33 and 27 BCE,

Octavian's unique powers were legitimated as a combination of the powers held by various

Roman officials in previous periods. The difference now was that those powers were united in

the hands of one very special Roman official, the princeps senatus or "first man of the Senate."

Octavian was not a king, his propaganda suggested, but merely one of many highly respected

and powerful Roman aristocrats. In any case, the vast powers he now wielded were retained

only for the good of the state, not for his own benefit, so the argument suggested.

In his famous "Res Gestae Divi Augusti" ("Achievements of the Divine Augustus"), for example,

Octavian recalled that, in 27 BCE when all the crises of state had passed, he had approached

the Roman Senate and tried to relinquish all of his powers. The Senate insisted that he keep

his powers and maintain the public order that he had garnered. The Senate then bestowed

upon Octavian the honorific title "Augustus," which carried not only secular but also religious

connotations. After that point, Augustus claimed that he had no more power than any other

senator but that no one was to precede him in authority.

That distinction is crucial for understanding the Principate. The implication of that claim is

that Augustus ruled Rome not through force or coercion but because he was universally

recognized as the Roman most able to maintain the public order that had been so frequently

and disastrously shattered before his advent. Such a claim should not be dismissed out of

hand; the men and women of Augustus' generation had seen a seemingly endless cycle of civil

war and bloodletting, a cycle brought joyously to an end by Augustus and his immediate

successors.

Under Augustus' reign, the Roman world grew strong and amazingly rich. Its people enjoyed

the benefits of a long peace made possible by the presence of a strong Roman executive who

could maintain public order and the rule of law, even if his own place within Roman society

was necessarily ambiguous and shrouded in legal and political fictions. When Augustus died

in 14 CE, Rome faced a new problem: managing the orderly succession of future emperors to a

position in Roman society that officially did not exist.

MLA:

Sizgorich, Tom. "Augustus." World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO, 2014. Web.

6 Jan. 2014.