* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Cancer is generally understood as a genetic or cellular disease

Vectors in gene therapy wikipedia , lookup

Microevolution wikipedia , lookup

Cancer epigenetics wikipedia , lookup

Frameshift mutation wikipedia , lookup

BRCA mutation wikipedia , lookup

Genome (book) wikipedia , lookup

Polycomb Group Proteins and Cancer wikipedia , lookup

Point mutation wikipedia , lookup

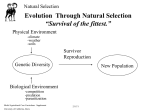

Biomedicine Workshop INADEQUACY PREDICTIVITY OF TUMOR-ASSOCIATED GENES. ARE CANCERS A REVERSIBLE DISEASE? by Mariano Bizzarri Professor of Biochemistry and Clinical Pathology in Oncology, Department of Experimental Medicine and Pathology, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Cancer is generally understood as a genetic or cellular disease, which results either from the overexpression or lack of expression of certain genes and related proteins. However, intensive research on cancer, along the lines depicted by the current epigenetic paradigm, has led to several anomalies and contradictions that cannot be fully explained within such reductionistic paradigm. It is generally thought that the first step in cancer initiation is a mutation in a single cell that must be able to pass its acquired abnormality to its progeny. This initiation results from a genetic mutation in a least one or a set of regulatory genes (proto-oncogenes) which then becomes oncogenes. Paradoxically, tumour progression is further explained as a sort of micro evolutionary Darwinian process, whereby the single mutated cells leads to a population of clonally derived cells. As a matter of fact, a single mutation is not enough to cause cancer: several stepwise genetic alterations (four independent mutations in four different genes) are necessary for full tumour development. Indeed, such a model is seriously questioned by several experimental data, suggesting that human transformed cells are the result of genome and signalling wide instability – leading to aneuploidy – rather than the consequence of point mutations that alters specific genes. Moreover, mutation rates of somatic as well as of cancer cells are very low; therefore is unlikely that such a combination of four mutations (experimentally and artificially induced) might occur spontaneously within a single cell in the appropriate order and fashion. A simple estimate, based on the known mutation rate of somatic cells of around 10-12 per nucleotide per generation, suggests the impossibility of such a stepwise accumulation of four independent mutations within a single cell and during the average life span of a human being. Moreover, actually there is no evidence that any of the socalled oncogenes is expressed at a higher rate in a primary cancer than in its normal tissue counterpart: in fact, it is very unlikely that alteration of a single key cellular factor may transform a normal cell into a cancer cell, under non artificial circumstances. Any way, if cancer onset were truly an event due to accumulation of mutations in a few key-genes, then, once the threshold has been crossed, there should be no way back towards normality. Nevertheless, this conclusion is not consistent with experimental data, related to spontaneous clinical regression or to dramatic phenotypic reversal obtained in vitro from cancer cell cultures. Normal cells situated in the wrong tissue degenerates into a cancer, meanwhile neoplastic cells introduced into a blastocyst or submitted to normal embryonic signals, become normal and contribute to the development of organised bodily structure. Thus heritable normal behaviour or phenotype can be restored under appropriate signals emerging from the environment, i.e. restoring a normal and strong morphogenetic field. It is highly unlike that this phenotypic reversal could be attributed to the reversion of multiple gene mutations that are claimed to be the cause of cancer. In fact, the control of cell growth and proliferation cannot be an exclusively internal cellular issue, when the cell belongs to an organism. More likely, it should be the breakdown of the space-temporal organization – a morphofunctional entity called “morphogenetic field” – and the resulting disruption of the normal signalling mechanism, that results in loss of coherence between cell and organism and further leads to the onset of cancer. Thus, the appearance of a tumour might signal that the properties of the field are gradually lost when the living structure is beyond its prime, i.e. when its morphogenetic field is weakened. The weakening and/or disruption of the original morphogenetic field also makes room for the influence of aberrant or artificial “pregnant entities”, i.e, morphogenetic driving forces, that may overwhelming or superpose it to the “originary” field. Dramatic changes in metabolic environment – related to diet or to epigenetic modifications – or altered structure in the overall neuroimmunoendocrine network, as well as rearrangements in the matter coherence state mediated by different factors, could deeply influence the physiologic structure and the genomic functioning of a living organism. Therefore cancer, and any transformation of the cellular organization, should be viewed as a result of a conflict between an organised morphology and the emerging of a new unpredictable teleion, towards which the biological system drifts, leading to a new and aberrant amorphous state.