* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download this PDF file - Toulon Verona Conference

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

E-governance wikipedia , lookup

Visual merchandising wikipedia , lookup

Social media marketing wikipedia , lookup

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Michael Aldrich wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Viral marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Customer relationship management wikipedia , lookup

Marketing research wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Customer experience wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Consumer behaviour wikipedia , lookup

Customer satisfaction wikipedia , lookup

Services marketing wikipedia , lookup

Service blueprint wikipedia , lookup

Online shopping wikipedia , lookup

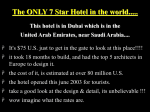

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS 14th Toulon-Verona Conference “Organizational Excellence in Services” University of Alicante - University of Oviedo (Spain) – September 1-3, 2011 pp. 799-814 – ISBN: 978 88904327-1-2 THE IMPACT OF HOTEL REVIEWS POSTED BY GUESTS ON CUSTOMERS’ PURCHASE PROCESS AND EXPECTATIONS Aurelio G. Mauri, Università IULM, Milano, Italy , [email protected] Roberta Minazzi, Ph.D., Università dell’Insubria, Como, [email protected] ABSTRACT From the first article published on the topic of electronic word-of-mouth – eWOM (Stauss, 1997) research has rapidly increased, underlining the importance of this phenomenon both in academic and business contexts. The purchasing behaviour of the customer has increasingly changed with the development of new technologies. Therefore, what had traditionally been defined as word-of-mouth (WOM) (Arndt, 1967; Koenig, 1985) needed to be reconsidered and studied in light of recent changes (Buttle, 1998; Breazeale, 2009). Electronic WOM through online reviews on specific websites, company websites, blogs and communities influences various steps of the consumer decision-making and purchasing processes (Schindler and Bickart, 2005) and his expectations of the service. The objective of the paper is to study the impact that customer feedback/reviews posted on “non-transactional” websites have on the consumer decision-making process and on tourist expectations in the hospitality industry, which is particularly affected by this new trend. Many travel services are now bought on the net using electronic distribution systems: flights, hotel stays, car rentals, etc. (Nielsen, 2010; PhoCusWright, 2010). Online reviews play a key role in purchasing travel services (Nielsen, 2010) and “non-transactional” website traffic increased by 4% from 2007 to 2009 despite a decrease for transactional websites (OTA, company websites, etc.) (PhoCusWright, 2009). Therefore, hotel companies should comprehend the way customer feedback influences other consumers’ decisions and expectations in order to develop specific marketing strategies that also consider the synergy among social media and the development of mobile technologies. Keywords: electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), word-of-mouse, hotel reviews, purchase behaviour, expectations INTRODUCTION The Internet is now the predominant means of travel shopping in European countries and has changed the way tourism information is distributed (Buhalis, Law, 2008; Law et al., 2008). 70% of French travellers and nearly 80% of German and U.K. travellers typically use the Internet when shopping for travel, at least as a source of information. The second source of information is personal recommendations from family and friends, which is true of 40% of German and U.K. tourists and less than 40% of French travellers (PhoCusWright, 2010). More recently, tourists have been able to benefit from a new and convenient way of gathering information directly when they arrive at their destinations thanks to the development of mobile technologies (Buhalis, Law, 2008). The advent of the Internet has brought about a word-of-mouth revolution. In fact, individuals can make their thoughts and opinions easily accessible to the global community of Internet users (Dellarocas, 2003). We can consider eWOM a form of communication that provides a mechanism to shift power from companies to consumers (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). In this context, online reviews play a key role in purchasing travel services (Nielsen, 2010) and ― non-transactional‖ website traffic has increased by 4% from 2007 to 2009 despite a decrease for transactional websites (Online Travel Agencies-OTA, company websites, etc.) (PhoCusWright, 2010). A study conducted by Gretzel (2007) on a sample of Tripadvisor users confirms the importance of online reviews during the step of travel planning especially in deciding ― where to stay‖ (77.9%). Virtual communities (TripAdvisor, VirtualTourist, LonelyPlanet) are the most-used travel websites (92.3%), especially for gathering information, evaluating alternatives, avoiding unenjoyable places and providing ideas. Online travel sales, especially for Hotels, account for only 7% in Europe while OTAs are the most-used means of travel booking (PhoCusWright, 2010). Key segments in online travel are: Online Travel Agencies (OTAs); suppliers’ direct websites; tour operators; online corporate booking tools; non transactional/media travel sites; emerging media and channels (for instance smart phones and social network such as Facebook and Twitter). These last two operators aim to facilitate and enrich online travel planning, enabling the customer to share information and experiences with other travellers. Actually, nontransactional websites can have two different goals: reviewing and trip planning (such as TripAdvisor and Lonely Planet) and Metasearch (such as Kayak, cheapflights) that compare the offers of different OTAs (Buhalis, O’Connors, 2005). On the contrary, emerging media and channels like social networks (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) are more oriented towards relationships among travellers even if more and more possibilities are given to the companies to directly create personal relationship with the customer (Pan et al., 2007; Jansen et al., 2009; Xiang, Gretzel, 2010). In this group of operators, mobile applications that allow customers to facilitate almost all the steps of the purchase process are the new frontier (I Phone, etc.) (Shankar, Balasubramanian, 2009; Sultan et al., 2009). This paper focuses on ― non-transactional‖ websites in the hospitality industry and aims to evaluate the influence of customer reviews on his purchase intentions and expectations. Finally, the study intends to verify whether the power of negative consumer comments can be minimized through appropriate company response. The issue is investigated by presenting an experimental study on the impact of online hotel reviews on consumer decision-making and expectations. 1. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPT OF WORD-OF-MOUTH 1.1. Word-of-mouth vs. electronic word-of-mouth The development of new technologies and the trends identified in the previous paragraph pointed out the need to reconsider the concept of word-of-mouth (WOM), as traditionally intended, in light of recent changes (Buttle, 1998; Breazeale, 2009). Arndt (1967) and Koenig (1985) define WOM as ― an oral, person-to-person communication between a receiver and a communicator whom the receiver perceives as noncommercial, regarding a brand, product or service‖. WOM involves the exchange of ephemeral oral or spoken messages between a contiguous source and a recipient who communicate directly in real life. Consumers are not thought to create, revise and record prewritten conversational exchanges about products and services. This kind of communication vanishes as soon as it is uttered, for it occurs in a spontaneous manner and then disappears (Buttle, 1998). Stern (1994) underlines that WOM is different from advertising because it is not influenced and paid for by the company. This increases the perception of credibility by the customers (Bateson, Hoffman, 1999; Ogden, 2001). Villanueva et al. 2008 and Trusov et al. 2009 found that customers acquired through eWOM add more long-term value to the firm than customers acquired through traditional marketing channels. By analysing these definitions, we can identify the main differences between the traditional concept of WOM and the new idea of eWOM. First of all, eWOM is not necessarily direct or oral because customers write their impressions on the net and they do not vanish immediately; on the contrary, other consumers can consult these reviews even after a long period of time (Buttle, 1998; Breazeale, 2008). In the electronic environment, the opinions that consumers post on the Web are seen by millions, are available for long periods of time, and may be encountered by purchasers at precisely the time they are electronically searching for information about a particular product or service (Ward, Ostrom, 2002). Secondly, eWOM communication is not limited to brands, products or services but can be related to an organization, destination, etc. (Buttle, 1998). Thirdly, although eWOM remains a source of information from the company and different from advertising, it is sometimes incentivized and rewarded (Buttle, 1998). This can create some problems with the credibility of the message, as the source of the message is unknown. In fact, in eWOM communication the information comes from individuals who have little or no prior relationship with the seeker (Xia, Bechwati, 2008; Schindler, Bickart, 2005). It is difficult for the consumer to determine the credibility of the message when it comes from total strangers (Chatterjee, 2001) with diverse backgrounds (Litvin et al., 2008). For this reason, sometimes online travel intermediaries require reviewers to provide personal identifying information (PII) (e.g., name, state of residence, gender, and date of visit/stay) (Xie et al., 2010). This is the case Tripadvisor, for example. According to Hennig-Thurau et al. (2004) eWOM is ― ...any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual, or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet‖ (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). Online WOM messages can be shared through posted reviews (consumer opinions on apposite websites), mailbags (customer opinions on the website of the seller), discussion forums, electronic mailing lists (consumer opinions sent by e-mail), personal e-mail, chat rooms (real time conversation on a topic) and instant messaging (one-to-one real conversation on the internet). Schindler and Bickart (2005) conducted a study on a sample of frequent internet shoppers and found that the most frequently-used source of online WOM is consumer reviews and the main reasons are: to gather information about brands or products by consulting the experience of a lot of people and to support or confirm a previously-made decision. Sometimes people search for information just for fun, without any real intention to purchase but this action, even if passive, can influence future purchase decisions. However, customer comments present some biased information. Firstly, people who post a comment on the net are generally extremely satisfied or extremely dissatisfied (Anderson, 1998; Hu et al., 2007; Litvin et al. 2008). Positive reviews refers to favourable experiences and a consequent recommendation of the product to other customers, whereas negative feedback refers to unfavourable experiences and are meant to dissuade others from buying that product. The customer can have an attitude of aggressive complaint or a more moderate attitude trying to alert other consumers to the risk of the product (Cheng et al., 2006). Secondly, it is also possible to identify purchasing bias because only consumers with a favourable disposition towards a product purchase the product and have the opportunity to write a product review (Hu et al., 2007). Thirdly, those who write a comment about a purchased product are influenced by features other than objective product quality, leading to a reporting bias in these reviews. By the way, the listener is generally conscious of this bias and filters the information (Banerjee and Fudenberg, 2004; Hu et al., 2006). Finally, it is sometimes possible to find fake positive or negative reviews posted by the company or by the competitors trying, in the first case, to improve the company’s reputation, and, in the second, to damage the reputation of a competitor (Dellarocas, 2003). Given the decontextualization, anonymity and bias, eWOM may appear nebulous to consumers. As a result, consumers’ interpretations of eWOM and subsequent purchase intention may be substantively affected by their pre-existing disposition toward the service provider (Xie et al. 2010). 1.2. Credibility of online customer reviews WOM can be analysed considering various dimensions (Mauri, 2002): valence (positive and negative); intensity (quantity of comments); speed (number of contacts in certain period of time); persistency (length in time); importance (role of comments in the customer decision-making process); credibility (in terms of assurance and confidence of the source of the message). In this study we focus especially on valence and credibility of online comments. Credibility of eWOM is influenced by informative aspects and normative cues (recommendation consistency, recommendation rating) that may be able to supplement the informational cues (Cheung, 2009). Argument strength concerns the quality of the information received. It is the extent to which the message receiver views the argument as convincing or valid in supporting its position. For example, the presence of details and personal identifying information (PII) of the reviewers (Xie et al., 2010) describing a first-hand experience and the consensus of other reviewers are generally cues of the message's validity (Schindler, Bickart, 2005; Park et al. 2007). On the contrary, a lack of negative comments and undetailed or very general messages are considered untrustworthy (Schindler, Bickart, 2005; Schlosser, 2005; Doh et al., 2009). Recommendation framing refers to the valence of the eWOM (positively framed or negatively framed) while recommendation sidedness refers to the content of the message that can contain only one-sided information (positive or negative) or two-sided information (both positive and negative). Two-sided information is generally considered more credible because of the consumer each product has positive and negative features. Therefore two-sided descriptions are perceived as more detailed information influencing the argument strength (Cheung, 2009). Another key factor is source credibility, which refers to the reputation of the reviewer that is sometimes conferred by the administrator of the website and other times with specific and formal ranking on the basis of the message’s helpfulness (Henning-Thurau, 2004). Due to the bias reported in the previous paragraph, the customer tries to find reviews consistent with his or her prior knowledge or expectations, increasing his perception of review credibility (Xie et al., 2010). In fact, Xia and Bechwati (2008) found that the influence of the comment depends on the cognitive personalization initiated by the reader. If he perceives the situation as familiar, he processes the information in a self-referential manner and the review becomes more credible, valid and trustworthy. Another important aspect that influences the credibility of an online consumer opinion is the website where it is posted. Feedback on corporate websites is generally considered less credible that those on non-transactional websites (such as Tripadvisor, Zoovers, etc.) (Park et al., 2007). With this in mind, some companies prefer to attach a link to these websites despite creating a guest comment page. The credibility of the review is therefore a key factor that leads the consumer to consider or disregard the message during the purchase decision process. 2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 2.1. The impact of online customer reviews on purchase intentions Academic studies on the topic of online word-of-mouth have pointed out the impact of consumer reviews on the purchase intentions and decisions of the customers. Online reviews on specific websites, company websites, blogs and communities influence various steps of the consumer decision-making and purchasing processes (Schindler, Bickart, 2005; Park et al., 2005; Buhalis, Law, 2008). Several recent studies on the topic of eWOM agree on the deep impact of online reviews on customer purchase intentions. An extant stream of work has looked at the economic impact of reviews on companies’ financial performances by means of numeric variables representing the valence (positive or negative) and volume of reviews. This hypothesis received strong support in prior empirical studies (Chevalier, Mayzlin 2006; Dellarocas, 2003; Dellarocas et al. 2006; Forman et al. 2008; Villanueva et al., 2008; Luo, 2009; Godes, Mayzlin 2009). The effect of eWOM and online travel reviews on consumer behaviour has also been studied in the travel and tourism industry – especially with reference to information searching, holiday planning and purchase decisions (Gretzel, Yoo, 2008; Gretzel et al., 2007; Litvin, et al., 2008; O´Connor, 2008; Papathanassis, Knolle, 2010; Sidali et al., 2009; Vermeulen, Seegers, 2009; Ye et al., 2009). Exhibit 1. The impact of online WOM on purchase decision making Source: Schindler R., Bickart B. (2005), Published 'Word of Mouth': Referable, Consumer-Generated Information on the Internet, in C. Hauvgedt, K. Machleit, R. Yalch (Eds.), Online Consumer Psychology: Understanding and Influencing Behavior in the Virtual World, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. (pp. 35-61). The valence (positive or negative) of the message is one of the most considered variables. Sen and Lerman (2007) found that the valence of the review (positive or negative) influenced consumer behaviour but in different ways depending on the kind of product (hedonic versun utilitarian). Also, the balance of positive and negative comments can be a factor considered by the customer. In fact, if the consumer perceives a low level of consensus he is believed to think that the authors of negative reviews are unable to use or evaluate the product. On the contrary, in the case of more consensus on the negative side the customer will develop negative inferences towards the product and the brand (Laczniak et al., 2001). In particular, various studies concentrate on the potentially more influential effect of negative than positive WOM because of the detrimental impact on businesses. A study of Chatterjee (2001) indicates that negative consumer reviews have negative effects on perceived company reliability and purchase intentions. The effect could be more negative in the case of a company unfamiliar to the consumer. Other authors have investigated the behaviour of the dissatisfied customer and found that he is more likely to express feelings to other people through negative WOM (Richins, 1983; Morris, 1988; Hart and Heskett, 1990; Tax, Brown, & Chandrashekaren, 1998). Bambauer-Sachse and Mangold (2011) confirm with their research that negative online product reviews have detrimental effects on consumer-based brand equity leading to a significant brand equity dilution, even if the brand is familiar to the customer. On the contrary, other studies affirm that the influence of negative WOM is not so different from that of positive comments (Ricci, Wietsma, 2006). Vermeule and Seegers (2008) found that both positive and negative reviews increase consumer awareness of hotel existence but, if the comments are negative, they lower consumer opinions. Neverthless, the hotel awareness generated compensates the effect of negative comments, especially if the quantity is low (Vermeulen, Seegers, 2008). Other streams of research focus on other variables that influence the structural process of how online consumer reviews influence purchase decisions. Park and Lee (2009) investigate and examine the role of national culture on these relationships by comparing U.S. and Korean consumers' behaviours. According to Xie et al. (2010) the presence of PII increases the credibility and subsequently purchase intention of the customer in the hospitality industry. Some other studies, in contrast to the ones previously cited, found that customer comments on the web are predictors of sales but do not influence them (Chen et al., 2004; Duan et al., 2008). Another important point is the nature of the product. According to some scholars, WOM recommendations play a significant role in consumers’ decision-making processes, especially when dealing with services or intangible products rather than with tangible ones (Murray, Schlacter, 1990; Gremler, 1994). Intangible services are particularly complex and difficult to evaluate prior to purchase and the perception of risk is higher because its quality is often unknown before consumption (Baccarani, Golinelli, 1992; Rosen, 2000; Dye, 2000; Zeithaml et al., 2006). Moreover, in the hospitality industry, WOM recommendations are even more influential due to the nature of inseparability between service production and consumption and the importance of the customer experience (Lindberg-Repo, 2001; Grönroos, 1999). The first hypothesis of the present research is: H1: The hotel booking intention of the customer is different depending on the valence of the review posted on “non-transactional” travel websites: it increases in the case of a prevalence of positive comments and decreases in the case of negative comments. 2.2. The impact of review valence on customers’ expectations The scholars of services marketing consider WOM as an antecedent of customer expectations. Grönroos (1982) believes that WOM is a key factor that influences expected quality along with marketing communication, company image, price and customers needs and values. Perceived quality is then the result of the comparison between expected quality and experienced quality (Grönroos, 1982; Oliver, 1980 and 1993; Zeithaml et al., 1985). Zeithaml et al. (1993) propose a model that conceptualizes the nature and determinants of customer expectations of services: among others, consumer experience and enduring service intensifiers influence desired service especially in the case of derived service expectations that are driven by other parties. During the step of information research customers gather information about the service from various known (WOM) and generally unknown (EWOM) sources trying to determine what to expect by a specific service. During the communication process customers share experiences that can have a positive or a negative valence (Mauri, 2002). H2: The level of expectation of the customer differs depending on the valence of the review posted on “non-transactional” travel websites: it increases in the case of prevalence of positive comments and decrease in the case of negative comments. 2.3. The impact of hotel reply on purchase intentions and customer expectations How can a Hotel try to minimize the impact on negative comments on booking intentions and on expectations? Recent studies suggest that the widespread use of eWOM and online hotel reviews can be an opportunity rather than a threat for hotel managers and operators (Litvin et al., 2008). Companies that understand the importance of WOM are taking advantage of online consumer reviews as a new marketing tool (Dellarocas 2003), posting product information and chatting on online forums. Godes and Mayzling (2009) use the term ― exogenous WOM‖ to describe the proactive actions of companies that induce their consumers to spread the word about their products online (Godes and Mayzlin 2004; Godes and Mayzlin 2009). Viral marketing campaigns are considered more and more important in combination with offline marketing strategies (van der Lans et al., 2010). Some firms even strategically manipulate online reviews in an effort to influence consumers’ purchase decisions (Dellarocas 2006). Chen and Xie (2008) conducted a study to try to understand the way a company should interact with consumer reviews to increase profits, trying to control online word-of-mouth. They found that the response of the company should change according to the type of product and the kind of information. Other studies confirm that the company should strategically respond to online consumer reviews (Chen, Xie 2005, Dellarocas 2006; Zhu and Zhang, 2010; Xie et al., 2010). However, no previous academic studies have yet explored the effect of company response to customers’ reviews on booking intentions and expectations of the customer. We also have to consider two kinds of problems that interfere with hotel operator response activity. On the one hand, the hotel operators are not completely conscious of the effect of online word-of-mouth on the customer and, consequently, they undervalue this phenomenon. Moreover, hotel managers sometimes do not have appropriate IT knowledge due to the customer-oriented approach of the service sector. IT has always been seen as an instrument to reach customers but rarely is it integrated into the company’s business strategy (Law, Jogaratnam, 2005; Law et al. 2008). On the other hand, a conflictual relationship between hotel companies and websites that publish travel reviews complicates the situation. Recently, replying to negative comments on the web has become easier for the hotel companies thanks to an improvement in the business relationship and cooperation among offline and online travel operators. Speaking with a few hotel operator we find out that they consider the possibility to reply to customers an important opportunity to increase customer perceptions of service quality and booking intentions. However, hotel managers’ reply can be considered not credible because not independent but related to the company (Buttle, 1998). The consumer could perceive that message very similar to advertising (Stern, 1994) also because the messages generally are not personalized. Therefore, it is interesting to address the following research question: RQ1: the hotel responses to customer reviews posted on “non-transactional” travel websites could have a positive and useful effect on customer booking intention and on his expectations? 3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY An experimental study was conducted to test the hypotheses and the research question in June 2011. To eliminate the possibility of bias, three scenarios were built around an unbranded hotel. In fact, brand familiarity can play an important moderating role in the consumer’s perception of comments: familiar hotel brands could be more resilient to review effects than unfamiliar brands (Chatterjee, 2001; Vermeulen and Seegers, 2008). Those involved in the survey were asked to imagine searching for a hotel for a weeklong holiday in an unknown location without any previous experience. This decision was meant to eliminate possible bias from the customers’ previous personal experiences. After the presentation of the context, the participant was asked to read other customers’ reviews of a hypothetical chosen hotel. The hotel reviews presented in the three scenarios were created by studying a few comments posted by customers on the main websites used by tourists (such as Tripadvisor). In fact, the structure was very similar to other existing websites but we changed the main recognition seals to avoid any kind of reference to well-known sites and therefore the influence of site brand image. For the same reason, other information about the hotel was also excluded from the survey (price, room amenities and services). The review consisted of a synthetic title, the ranking, the date of the review and the comment of the customer. They were presented in order of date published for the period January 2011-until now (period of research). The creation of three different questionnaires aimed to verify the previously-stated hypotheses. To do that, the first scenario presented a prevalence of positive reviews (7 vs. 3), the second scenario presented the opposite situation, that is, a prevalence of negative comments (7 vs. 3), the third scenario presented the previous context (prevalence of negative comments) but, in this case, the reply of the hotel manager was reported. The order of positive and negative reviews was counterbalanced to control any possible order effect (Carlson et al., 2006). To increase comment credibility, we used two-sided information (Henning-Thurau, 2004). At the end of the comments, participants were asked to answer a few questions to try to understand the soundness of the hypothesis (H1 and H2) and to answer the research question (RQ1). Purchase intention was evaluated on a 7-point scale (1-most likely not to buy, 7-most likely to buy) as was the level of expectation (1 for low expectations, 7 for high expectations) Respondents Profile 360 online questionnaires were sent to undergraduate and graduate italian students with a result of 102 respondents (response rate of 28.9%). The choice was considered appropriate from the age point of view because, according to Italian statistics, more than 30% of people that buy online are between the ages of 25 and 34 (Istat, 2009). Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups corresponding to three different scenarios. Respondents are mainly women (73.5%) between the ages of 18 and 25 (82.4%). This composition is also the main limit of the study, that is a pilot study and need to be extended. Table 1 Respondents features: age and gender age 18-25 Count scenario 1 % within scenario 1 % of Total Count scenario 2 % within scenario 2 % of Total Count scenario 3 % within scenario 3 % of Total Count Total % of Total 4. 26-35 21 63,6 20,6 30 96,8 29,4 33 86,8 32,4 84 82,4 6 18,2 5,9 1 3,2 1,0 3 7,9 2,9 10 9,8 > 36 Total 6 18,2 5,9 0 0,0 0,0 2 5,3 2,0 8 7,8 33 100,0 32,4 31 100,0 30,4 38 100,0 37,3 102 100,0 man 7 21,2 6,9 9 29,0 8,8 11 28,9 10,8 27 26,5 gender woman 26 78,8 25,5 22 71,0 21,6 27 71,1 26,5 75 73,5 Total 33 100,0 32,4 31 100,0 30,4 38 100,0 37,3 102 100,0 FINDINGS A first result to be analyzed is that more than 76% of respondents consult comments of other customers before booking a hotel. This confirms the importance of online customer feedbacks stated in the previous part of the paper. The first hypothesis (H1) claims that there is a positive correlation between hotel booking intention of the customer and valence of the review posted on ― non-transactional‖ travel websites. In particular, it increases in the case of a prevalence of positive comments and decreases in the case of negative comments. Comparing the mean of each scenario (table 2), the average score of booking intention rises from 4.10 to 4.52 shifting the scenario from 2 (prevalence negative reviews) to 1 (prevalence of positive reviews). The correlation, by means of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, supports H1 (table 3) and demonstrates a positive (rs= 0.246) and significant (p<0.05) correlation between booking intention and valence of the message. Table 2 Booking Intention and level of expectations according to each scenario Booking intention Scenarios Scenario 1 Prevalence of positive reviews Mean Scenario 2 Prevalence of negative reviews Mean Scenario 3 Prevalence of negative reviews with hotel reply Mean Std. Deviation Std. Deviation Std. Deviation Mean Total Std. Deviation Level of expectations 4.52 4.58 1.121 1.001 4.10 4.39 0.900 1.116 3.82 4.34 1.205 1.214 4.13 4.43 1.125 1.113 The second hypothesis (H2) claims that there is a positive correlation between the level of customer expectations and valence of the review posted on ― non-transactional‖ travel websites. Table 2 shows, an average score (M=4.58) higher in the case of prevalence of positive comments than in the case of negative comments (M=4.39). However, we cannot statistically demonstrate a relationship between reviews’ valence and level of customer expectations because, as shown in table 3, the correlation is not significant (p>0.1). Research questions (RQ1) investigated whether the hotel responses to customer reviews posted on ― non-transactional‖ travel websites could have a positive and useful effect on customer booking intention and on his expectations. Table 2 shows that in the case of hotel managers’ responses the average score descreases (M=3.82). The correlation by means of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient demonstrates a positive (rs= 0.209) and significant (p<0.05) correlation between booking intention and the presence of hotel responses (table 4). This result supports the position that considers hotel responses as less credible because not independent from the organization. However, also in this case we cannot demonstrate a relationship between reviews’ response and level of customer expectations because, as shown in table 4, the correlation is not significant (p>0.1). Table 3 Correlation between review valence (positive vs. negative) and booking intention and level of expectations (H1 and H2) Dimensions rs Sig. Booking intention 0,246 0,014 Level of expectations 0,101 0,313 Table 4 Correlation between hotel response presence and booking intention and level of expectations (RQ1) Dimensions 5. rs Sig. Booking intention -0,209 0,038 Level of expectations - 0,062 0,534 DISCUSSION As expected, the results obtained through the analysis support the first hypothesis of the study that consider valence of reviews posted on ― non-transactional‖ travel websites and hotel booking intention positively related, confirming the persuasive impact that positive comments can have on customer decision making process (Sen, Lerman, 2007; Sparks, Browning, 2011). The most interesting research point of the study was to verify the effect on hotels’ reply to negative comments on booking intention and expectations. Results show that including the hotel responses to customer reviews has a negative effect on customer booking intention. This confirms the approach that considers the hotel’s reply more similar to advertising and therefore perceived by the customer as less credible because not independent from the organization. Hotel operators should try to reduce negative WOM and stimulate positive reviews through personalized activities that increase customer satisfaction, for example: improving the level of service delivered to the customer by trying to reduce the volume of negative comments; improving the service recovery when the customer is already at the hotel, stimulating complaints; conducting customer satisfaction surveys and personal interviews and developing guest comment areas on the websites when the customer has already gone home. The effect of online service recovery policies, by means of hotels’ reply to negative comments on ― non transactional‖ websites, have not the same effect of personal complaint handling. The message could not be read by the customer who posted the review and other customers perceive it as commercial communication. The hotel company should find other ways to create an interaction with customers on the web, using social media and stimulating positive online and offline word-of-mouth. 6. CONCLUSIONS The paper demonstrates that booking intentions in the hospitality industry are influenced by valence (positive or negative) of online reviews posted on travel ― non transactional‖ websites, providing further theoretical and practical knowledge on this topic. In particular, online travel reviews is confirmed to be an important source of information which influences customer decision making process and booking intentions. The presence of hotel managers’ reply to customer reviews is not considered a key factor by the customer. On the contrary, it has a negative impact on customer booking intention. The source of information in this case is probably seen as not spontaneous and not independent from the organization. These results, in light of managerial implications described in the previous paragraph, can support hotel operators in defining integrated communications strategies based on a synergic use of new media and technologies, without forgetting the importance of personal relationships and service recovery when the customer is already at the hotel. In fact, service quality evaluation and customer satisfaction remains key factors stimulating positive online customer reviews. 7. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH The present paper is based on an explanatory study that presents some limitations. First of all, it is based on a convenience sample and respondents are mainly concentrated in a specific age and gender group. It is necessary for the future to continue the research on a wider sample. This could be helpful also to verify the relationship between review valence and customer expectations resulted not significant in this study. Secondly, the experimental approach limits the investigation to selected variables. In fact, many other variables can influence booking intentions and customer expectations such as personal interests of the customer. Thirdly, even if credibility standards were respected, creating the reviews content is a limitation to what information was presented in the scenarios. Future research could explore the relationship between hotel reply to online customer reviews and company image and reputation. Moreover, it could be interesting to verify the actual booking behaviour of the consumer, not only the intention in the pre-purchase step, and the influence of social media on eWOM. REFERENCES Anderson, E.W. 1998. Customer Satisfaction and Word of Mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1 (1), 5-17. Arndt, J. 1967. The role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. Journal of Marketing Research, 4 (3), 291–295. Baccarani, C., Golinelli, G.M. 1992. L’impresa inesistente: relazioni fra immagine e strategia. Sinergie, 29. Bambauer-Sachse, S. , Mangold, S. 2011. Brand equity dilution through negative online word-ofmouth communication. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18, 38–45. Banerjee, A., Fudenberg, D. 2004. Word-of-Mouth Learning. Games and Economic Behavior, 46, (1), 1-22. Bateson, E.G., Hoffman, K.D. 1999. Managing Service Marketing, Dryden Press, Boston. Bolton; R.N., Lemon; K.N., Verhoef, P.C. 2004. The Theoretical Underpinnings of Customer Asset Management: A Framework and Propositions for Future Research. Academy of Marketing Science Journal; 32 (3), 271-292. Breazeale, M. 2009. Word of mouse. An assessment of electronic word-of-mouth research. International Journal of Market Research, 51 (3), 297-319. Buhalis, D., Law, R. 2008. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29 (4), 609-623. Buhalis, D., O’Connors, P. 2005. Information Communication Technology Revolutionizing Tourism. Tourism Recreation Research, 30 (3), 7-16. Buttle, F. 1998. Word of mouth: understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6 (3), 241–254. Carlson, K.A., Meloly, M.G., Russo, J.E 2006. Leader-driven primacy: Using attribute order to affect consumer choice. Jounal of Consumer Research, 32 (4), 513-518. Chatterjee, P. 2001. Online Reviews: Do Consumers Use Them?. Advances in Consumer Research, 28, 129-133. Chen, Y., Wu, S.-Y., Yoon, J. 2004. The impact of online recommendations and consumer feedback on sales, Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems -ICIS, 711–724. Chen, Y., Xie, J. 2005. Third-Party Product Review and Firm Marketing Strategy. Marketing Science, 24 (2), 218-240. Chen, Y., Xie, J. 2008. Online Consumer Review: Word-of-Mouth as a New Element of Marketing Communication Mix. Management Science, 54 (3), 477-491. Cheng, S., Lam, T., Hsu, C.H.C. 2006. Negative Word-of-Mouth Communication Intention: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 30, 95-116. Cheung, M.Y., Luo, C., Sia, C.L., Chen, H. 2009. Credibility of Electronic Word-of-Mouth: Informational and Normative Determinants of On-line Consumer Recommendations. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 13 (4), 9–38. Chevalier, J.A. & Mayzlin, D. .2006. The effect of word of mouth on sales: online book reviews. Journal of Marketing, 43 (3), 345–354. Dellarocas, C. 2003. The Digitization of Word of Mouth: Promise and Challenges of Online Feedback Mechanisms. Management Science, 49 (10), 1407-1424. Dellarocas, C. 2006. Strategic manipulation of internet opinion forums: implications for consumers and firms. Management Science, 52 (10), 1577–1593. Doh, S-J., Hwang J-S. 2009. How Consumers Evaluate eWOM (Electronic Word-of-Mouth) Messages. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12 (2), 193-197. Duan, W., Gu, B., Whinston, A.B. 2008. Do online reviews matter? — An empirical investigation of panel data. Decision Support Systems, 45, 1007-1016. Dye, R. 2000. The Buzz on Buzz. Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dic., 139-146. Forman, C., Ghose, A., Wiesenfeld, B. 2008. Examining the Relationship Between Reviews and Sales: The Role of Reviewer Identity Disclosure in Electronic Markets. Information Systems Research, 19 (3), 291-313. Godes, D., Mayzlin, D. 2004. Using Online Conversations to study Word-of-Mouth Communication. Marketing Science, 23 (4), 545-560. Godes, D., Mayzlin, D. 2009. Firm-Created Word-of-Mouth Communication: Evidence from a Field Test. Marketing Science, 28 (4), 721-739. Goldsmith, R.E., & Horowitz, D. (2006). Measuring motivations for online opinion seeking. Journal of Interactive Advertising 6. Retrieved June 10, 2009. Gremler, D.D., Gwinner, K.P., Brown, S.W. Generating positive word-of-mouth communication Gretzel, U. 2007. Online Travel Review Study. Role and Impact of Online Travel Reviews, Laboratory for Intelligent Systems in Tourism, Texas A&M University. Gretzel, U., Yoo, K.H. 2008. Use and impact of online travel reviews. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2, 35-46. Grönroos, C. 2000. Service management and marketing. A customer relationship management approach. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. Haksever, C., Render, B., Russel, R.S., Murdick, R.G. 2000. Service Management and Operations, sec. ed., Prentice Hall, Upple Saddle River, N.J. Hart, C. W. L., Heskett, J. L. 1990. The profitable art of service recovery. Harvard Business Review, 68 (4), 148-156. Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K.P., Walsh, G., Gremler, D.D. 2004. Electronic Word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: what motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet?. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18 (1), 38-52. Hu, N., Pavlou, P.A., Zhang, J. 2009. Overcoming the J-shaped distribution of product reviews. Communications of the ACM, 52 (10), doi>10.1145/1562764.1562800. Jansen, B.J., Zhang, M., Sobel, K., Chowdury, A. 2009. Twitter Power:Tweets as ElectronicWord of Mouth. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60 (11), 2169–2188. Koenig, F. 1985. Rumor in the Market Place: The Social Psychology of Commercial Hearsay, Auburn House Publishing Company, Dover. Laczniak, R. N., DeCarlo, T. E., Ramaswami, S. N. 2001. Consumers’ responses to negative word-ofmouth communication: An attribution theory perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 11 (1), 57-73. Law, R., & Jogaratnam, G. 2005. A study of hotel information technology applications‖, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 17 (2), 170-180. Law, R., Leung, R, Buhalis, D. 2008. Information Technology Applications in Hospitality and Tourism: A Review of Publications from 2005 to 2007. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 26 (5), 599-623. Lindberg-Repo, K. 2001. Word-of-mouth Communication in the Hospitality Industry, Cornell Center for Hospitality Research. Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. 2008. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management‖, Tourism Management, 29 (3), 458–468. Lovelock, C., Wright, L. 1999. Principles of Service Marketing and Management, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J. Luo, X. 2009. Quantifying the Long-Term Impact of Negative Word of Mouth on Cash Flows and StockPrices. Marketing Science, 28 (1), 148-165. Mauri A.G. 2002. Le prestazioni dell’impresa come comunicazione ― di fatto‖ e il ruolo del passaparola. Sinergie, n. 59. Morris, S. 1988. How many lost customers have you won back today? An aggressive approach to complaint handling in the hotel industry. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 1, 86-92. Murray, K.B. 1991. A test of services marketing theory: consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing, 55, 10–25. Murray, K.B., Schlacter, J.L. 1990. The impact of services versus goods on consumers’ assessment of perceived risk and variability. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 18 (1), 51-65. Nielsen 2010. Global trends in online Shopping. Ogden, M. 2001. Marketing truth: Hearing is believing. The Business Journal,16 (52), 17. Oliver, R.L. 1980. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decision. Journal of Marketing Research, 17, 460-469. Oliver, R.L. 1993. A conceptual model of service quality and service satisfaction: compatible goals, different concepts‖, in Swartz T.A., Bowen D.E., Brown S.W., Advances in Services Marketing and Management: Research and Practice, vol. 2, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT. Pan, B., MacLaurin, T., Crotts, J.C. 2007. Travel Blogs and the Implications for Destination Marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 46 (1), 35-45. Park, C., Lee, T.M. 2009. Antecedents of Online Reviews' Usage and Purchase Influence: An Empirical Comparison of U.S. and Korean Consumers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23, 332-340. Park, D-H., Lee, J., Han, I. 2007. The effect of On-Line Consumer Reviews on Consumer Purchasing Intention: The moderating Role of Involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11 (4), 125-148. Pekar, V., Ou, S. 2008. Discovery of subjective evaluations of product features in hotel reviews. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14 (2), 145–155. PhoCusWright 2010. Technology and Independent Distribution in the European Travel Industry. PhoCusWright. 2010. Consumer Travel Report. Ricci, F., Wietsma, R.T.A. 2006. Product Review in Travel Decision Making. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, pp. 296-307. Richins, M.L. 1983. Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied customers: a pilot study. Journal of Marketing, 47 (1), 68–78. Rosen, E. 2000. The Anatomy Of Buzz : How To Create Word-Of-Mouth Marketing, Doubleday, New York. Schindler, R., Bickart, B. 2005. Published 'Word of Mouth': Referable, Consumer-Generated Information on the Internet, in C. Hauvgedt, K. Machleit, R. Yalch (Eds.), Online Consumer Psychology: Understanding and Influencing Behavior in the Virtual World, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 35-61. Schlosser, A., Kanfer, A. 2002. Impact of product interactivity on searchers’ and browsers’ judgments: Implications for commercial Web site effectiveness. Paper presented at the 2001 Online Consumer Psychology Conference, Seattle, WA. Sen, S., Lerman, D. 2007. Why are you telling me this? An examination into negative consumer reviews on the web. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21, 4, 76–94. Shankar, V., Balasubramanian, S. 2009. Mobile Marketing: A Synthesis and Prognosis‖, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23,118–129. Sidali, K.L., Schulze, H., Spiller, A. 2008. The Impact of Online Reviews on the Choice of Holiday Accommodations. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2, 35-46. Sparks, B.A., Browning, V. 2011. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tourism Management, doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.12.011. Stauss, B. 1997. Global Word of Mouth. Service Bashing on the Internet is a Thorny Issue. Marketing Management, 6 (3), 28 –30. Stern, B. 1994. A revised model for advertising: multiple dimensions of the source, the message, and the recipient. Journal of Advertising, 23, 2, 5–16. Sultan, F., Rohm, A.J., Gao, T.T. 2009. Factors Influencing Consumer Acceptance of Mobile Marketing: A Two-Country Study of Youth Markets. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23, 308–320. Tax, S. S., Brown, S.W.,& Chandrashekaren, M. 1998. Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62 (2), 60-76. through customer-employee relationships. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12 (1), 44-59. Trusov, M., Bucklin, R.E., Pauwels, K. 2009. Effects of Word-of-Mouth Versus Traditional Marketing: Findings from an Internet Social Networking Site. Journal of Marketing, 73, 15477185 (electronic). Van der Lans, R., van Bruggen, G., Eliashberg, J., Wierenga, J. 2010. A Viral Branching Model for Predicting the Spread of Electronic Word of Mouth. Marketing Science, 29 (2), 348–365. Vermeulen, I.E., Seegers, D. 2009. Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tourism Management, 30 (1), 123-127. Villanueva, J., Yoo, S., Hanssens, D.M. 2008. The Impact of Marketing-Induced Versus Word-ofMouth Customer Acquisition on Customer Equity Growth. Journal of Marketing, 45 (1), 48-59. Ward, J., Ostrom A. 2002. Motives for Posting Negative Word of Mouth Communications on the Internet. Advances in Consumer Research, 29 (1), 428-430. Xia, L., Bechwati, N.N. 2008. Word of Mouse: The Role of Cognitive Personalization in Online Consumer Reviews. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 9 (1). Xiang, Z., Gretzel, U. 2010. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31, 179–188. Xie, H.J., Miao, L., Kuo, P-J., Lee, B-Y. 2011. Consumers’ responses to ambivalent online hotel reviews: The role of perceived source credibility and pre-decisional disposition. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 178–183. Ye, Q., Law, R., Gu, B. 2009. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28, 180–182. Zeithaml V.A, Berry L.L., Parasuraman A. 1993. The Nature and Determinants of Customer Expectations of Service‖, in Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21 (1), 1-12. Zeithaml, V.A., Bitner, M.J. and Gremler, D.D 2006. Services Marketing. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Zhu, F., Zhang, X. 2010. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: the moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. Journal of Marketing, 74, (2), 133–148.