* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Selling and Marketing in the Entrepreneurial Venture

Online shopping wikipedia , lookup

Product lifecycle wikipedia , lookup

Social media marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Service parts pricing wikipedia , lookup

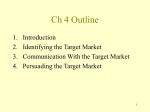

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Subscription box wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Pricing strategies wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Visual merchandising wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Segmenting-targeting-positioning wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Market penetration wikipedia , lookup

Customer experience wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Multi-level marketing wikipedia , lookup

Supermarket wikipedia , lookup

Global marketing wikipedia , lookup

Customer relationship management wikipedia , lookup

Customer satisfaction wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Customer engagement wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup

Marketing strategy wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

Sales process engineering wikipedia , lookup