* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Commensal Bacteria Shape Intestinal Immune System

Lymphopoiesis wikipedia , lookup

DNA vaccination wikipedia , lookup

Social immunity wikipedia , lookup

Molecular mimicry wikipedia , lookup

Polyclonal B cell response wikipedia , lookup

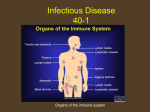

Immune system wikipedia , lookup

Adoptive cell transfer wikipedia , lookup

Adaptive immune system wikipedia , lookup

Cancer immunotherapy wikipedia , lookup

Immunosuppressive drug wikipedia , lookup

Innate immune system wikipedia , lookup

Commensal Bacteria Shape Intestinal Immune System Development The intestine is colonized with vast societies of microbes that promote mucosal immune system development and contribute to host health Heather L. Cash and Lora V. Hooper icrobes have a knack for making us sick. Until recently, many of these encounters proved deadly. In Guns, Germs, and Steel, evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond argues that such interactions were a primary force shaping human history. Therefore, it is not surprising that human-microbe interactions often are viewed through the lens of conflict. The proliferation of antibacterial consumer products underscores the prevailing idea that human-bacterial contact is something to be controlled or avoided. However, this understanding of human-microbe relationships is changing. An accumulating body of evidence indicates that we maintain mutually beneficial relationships with the microbes that cohabit our bodies, suggesting a profound intertwining of human and microbial biology. Wielding sophisticated new molecular tools, investigators in a number of labs are learning about the extent to which gut microbes drive intestinal immunity. These studies are revealing that the functions of our gut immune system are only partially encoded in our genes, and require cues from our microbial partners for full development. As a consequence, disrupting these beneficial host-bacterial relationships with antibiotic treatments may pave the way for immunologic diseases. M Intestinal Bacteria: Partners in Human Metabolism The domestication of our microbial partners begins early in life. Starting at birth, humans and other mammals are colonized with diverse societies of bacteria that cover the surfaces of the skin and the gastrointestinal tract, both of which are exposed to the outer world. The vast majority of these indigenous microbes reside in the intestine, where they are in continuous and intimate contact with host tissues, and where they outnumber the surrounding host cells by at least an order of magnitude. The term “commensal” is frequently used to describe the relationship between humans and their intestinal bacterial cohorts. Cobbled together from Latin roots, the term means “at table together.” This word seems especially appropriate because humans and other mammals depend heavily on their gut bacteria to extract maximum nutritional value from their diets. More than 20 years ago Bernard Wostmann and his colleagues at the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Ind., discovered that “germ-free” rats, which are microbiologically sterile and therefore lack intestinal microbes, require nearly 30% more calories to maintain their body weight than do their normally colonized counterparts. In an environment where nutrients are in short supply, natural selection would likely favor such host-microbe associations, which may explain why such relationships evolved in the first place. The vastness and diversity of the microflora ensure that this population maintains an array of metabolic talents, allowing its members to break down a variety of dietary compounds. The benefits associated with these host-microbial alliances flow the other way as well. In return for their metabolic contributions, gut bacteria are provided with a warm, protected, and nutrient-rich habitat in which to multiply. The very complexity that allows gut microflora to be valuable partners in human dietary metabolism poses serious challenges to micro- Heather L. Cash is a Graduate Student in the Molecular Microbiology Program and Lora V. Hooper is an Assistant Professor at the Center for Immunology, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 / ASM News Y 77 bial ecologists. Because intestinal bacteria are adapted to an anaerobic environment, many species in this population are difficult or impossible to culture outside the intestine, making it difficult to enumerate the membership of the gut’s microbial societies. However, new molecular techniques are allowing investigators to make inroads on this challenge. These techniques focus primarily on 16S rRNA genes, which are common to all bacteria but whose precise sequences vary between species. By analyzing the 16S rRNA sequences in such populations, microbial ecologists can sidestep the need to culture gut bacteria and thus can identify and quantify the inhabitants of this mixed microbial community. Although we still have a long way to go to get a clear picture of this society, some general themes have been established. Mammalian young are sterile in utero and become colonized as they are born. The intestines of human babies initially contain large numbers of facultative anaerobes, including Escherichia coli and streptococci. Such species decline in number during a critical postnatal transition: weaning from mother’s milk onto a solid diet rich in plant polysaccharides. During this same period, obligate anaerobes such as Bacteroides and Clostridium species gain a foothold, ultimately becoming the dominant occupiers of the adult gut ecosystem. The Intestinal Immune System Is a Complex Network of Interacting Cells The need to corral these microbial metabolic workhorses has driven the evolution of a vast and complex intestinal immune system. The host cells that constitute this immune network patrol and defend intestinal surfaces, keeping commensal bacteria from penetrating host tissues and causing serious problems such as inflammation and sepsis. However, maintaining these large microbial populations to serve host nutritional needs dictates that the intestinal immune system tolerate intestinal microbial antigens. Exactly how this tolerance develops and is maintained is a mystery. The intestinal epithelium presents the first line of defense against invading or attaching bacteria. In addition to presenting a physical barrier to microbial penetration, the epithelium plays a more active role by producing and secreting 78 Y ASM News / Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 large quantities of antimicrobial peptides. Small-intestinal Paneth cells are key effectors of this type of innate defense (Fig. 1). These specialized epithelial cells harbor secretory granules that contain high concentrations of a number of microbicidal proteins. Experiments carried out by André Ouellette and his colleagues at the University of California, Irvine, have shown that Paneth cells somehow sense bacteria and react to their presence by discharging their granule contents into the gut lumen. Such rapid-fire antimicrobial responses are part of the innate immune system, which enables the gut to deal quickly with invading microbes and to contain commensal populations. In contrast to innate immune defenses, adaptive immune responses develop more slowly but result in a targeted, precise response. As in other parts of the body, adaptive immune responses in the gut require the activation and multiplication of B- and T-lymphocytes, which undergo key portions of their development in gut-specific lymphoid structures called Peyer’s patches (Fig. 1). These structures punctuate the length of the small intestine, acting as incubators for developing B- and T-lymphocytes and ensuring that these cells mature with input from commensal microbial populations in the lumen. Lymphocytes dispatched from Peyer’s patches are thus primed to patrol the length of the intestine for microbial interlopers and to respond to pathogens. In addition to Peyer’s patch-derived lymphocytes, the gut harbors a large population of T-cells that insinuate themselves between intestinal epithelial cells, and are thus termed intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). Because the intestine has a vast surface area, these cells represent one of the largest populations of immune cells in the body, yet their functions are still poorly understood. Even the site of their development remains controversial. For example, Hiromichi Ishikawa and his colleages at the Keio University School of Medicine in Tokyo have evidence that these T cell populations develop entirely in the gut, and are thus uniquely primed to deal with local conditions. However, other investigators, including Gerard Eberl and Dan Littman of the New York University School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., and Delphine Guy-Grand and her colleagues at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, have provided evidence indicating that these cells develop first in the thymus and then home FIGURE 1 The small intestinal immune system consists of a complex network of interacting cell populations. The intestinal epithelium presents a physical barrier to microbial penetration. In addition, Paneth cells, specialized epithelial cells located at the base of small intestinal villi, actively secrete antimicrobial proteins in response to bacterial signals. Such rapid-fire innate immune responses are bolstered by precisely targeted adaptive immune responses that are slower to develop. The B- and T- lymphocytes that carry out such targeted responses develop in Peyer’s patches, specialized lymphoid structures found at intervals along the length of the small intestine. Peyer’s patch dendritic cells sample bacterial antigens and present them to the maturing lymphocytes. The B and T cells eventually exit the Peyer’s patch and guard against microbial penetration by patrolling the subepithelial regions throughout the intestine. to the gut, where they proliferate in response to local signals. Despite the ongoing debate about their origins, the positioning of IELs at the front lines of intestinal defense suggests that they play an important role in maintaining immune homeostasis with commensal bacterial populations. Germ-Free Mice: Unveiling Bacterial Contributions to Intestinal Immunity The cells of the gut immune system develop in proximity to enormous populations of commensal bacteria in the intestinal lumen. While epithelial cells are in direct contact with commensal bacteria, B- and T-lymphocytes are usually separated from microbial populations in the gut by a single epithelial layer. With such a slim cellular partition, resident bacteria are poised to influence the development of the gut’s innate and adaptive immune systems. To study how intestinal microflora contribute to gut immunity, investigators often use animals that have been raised without contact with microorganisms, taking advantage of a breeding system that was developed roughly 50 years ago by James Reyniers at the University of Notre Dame. Animals are housed and bred inside sterile isolators (Fig. 2) and are manipulated using gloves that are built into the isolator walls. Isolator provisioning is not a trivial task, as food, water, and bedding must be autoclaved inside stainless steel cylinders, which are then “docked” to the isolator before the supplies are imported. Animals that would otherwise be colonized can be derived germ-free by cesarean section, taking advantage of the fact that young animals developing in the uterus of a healthy mother are free of microbes. Typically, the uterus containing live pups is removed aseptically from the mother, passed into a sterilizing solution, and Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 / ASM News Y 79 FIGURE 2 Use of flexible film isolators for maintaining germ-free mice. Germ-free mice develop without any contact with the microbial world, and are thus an essential tool for defining which intestinal immune system functions require interactions with commensal bacteria for full development. The germ-free environment is created inside sterile plastic chambers (left panel) that can accommodate a number of mouse cages. Air is supplied to each isolator by a blower attached to a filter, which allows the air to be sterilized before it enters the isolator. Isolator interiors are sterilized by spraying with a dilute solution of Clidox (chlorine dioxide), and manipulations in the isolator are carried out through neoprene gloves. Sterile supplies such as food, water, and bedding are autoclaved in a stainless steel cylinder (right panel) and are transferred into the isolator through a double-door port. then transferred into a germ-free isolator. The pups are immediately removed and fostered to germ-free lactating females. Although this is now a relatively straightforward process, the first generations of germ-free mice were derived without benefit of germ-free foster mothers and had to be laboriously hand-reared. Bacterial Contributions to Innate Immunity Germ-free mice have yielded a number of valuable clues about how commensal bacteria shape intestinal innate immune responses. For instance, commensal microbes alter the expression of angiogenin-4, a bactericidal protein produced in the mammalian gut, according to Jeffrey Gordon and colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. Although its name suggests a role in the formation of new blood vessels, this protein is in fact a swift and effective bacterial killer. Synthesized and secreted exclusively by Paneth cells (Fig. 3), angiogenin-4 specifically targets gram-positive organisms such as Listeria monocytogenes and Enterococcus fae- 80 Y ASM News / Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 calis, while leaving gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli largely untouched. Such specificity may assist in establishing and maintaining the predominantly gram-negative bacterial populations found in intestines of adults. Commensal bacteria stimulate angiogenin-4 synthesis during a key developmental transition in early postnatal life. In mice that have a normal gut flora, angiogenin-4 expression increases dramatically when young mice switch from mother’s milk to a regular diet and quickly reaches adult levels. By contrast, germ-free mice never achieve high angiogenin-4 expression levels, indicating that full expression of angiogenin-4 in Paneth cells requires interactions with gut bacteria. However, this deficiency is reversible. By exposing germ-free mice to the mixture of intestinal bacteria found in their colonized counterparts, angiogenin-4 levels rapidly rise to match those found in conventionally colonized mice. The early postnatal expression pattern of angiogenin-4 shows that commensal bacteria can influence the composition of the developing Paneth cell antimicrobial arsenal. This suggests that bacteria and host may collaborate in shaping the composition of the evolving gut microbial community during weaning. Moreover, by inducing an abundance of this bactericidal protein, commensal bacteria may help to ensure that rapid-fire innate immune responses are primed and ready in the event that a pathogen is encountered. However, important questions remain, including how bacterial signals are relayed to Paneth cells to alter antimicrobial protein expression and whether other Paneth cell antimicrobial proteins are regulated by interactions with commensal flora. FIGURE 3 Bacterial Contributions to Adaptive Immunity Germ-free animals likewise are providing compelling evidence that commensal bacteria serve as a driving force in the development of the gut adaptive immune system (see table). For example, commensal bacteria play crucial roles in promoting B cell development in Peyer’s patches, which are underdeveloped in germBacterial contributions to small intestinal innate immunity. Commensal bacteria trigger the free mice, according to John Cebra expression of angiogenin-4, a bactericidal protein produced in small intestinal Paneth cells. angiogenin-4 specifically targets gram-positive bacteria, while gram-negative organisms are of the University of Pennsylvania in spared. This interaction may be important for establishing and maintaining the predominantly Philadelphia and his collaborators. Gram negative bacterial populations found in the adult intestine. Furthermore, these findings When commensal bacteria colonize suggest that commensal bacteria play a central role in shaping the composition of the Paneth cell antimicrobial arsenal. The molecular signals that commensal bacteria use to the intestine, they initiate a series of communicate with Paneth cells are unknown. reactions, including those that lead to transient expansion of germinal center reactions between B and T cells in the Peyer’s patches (Fig. 1) and increased stimulate B cell IgA production. Dendritic cells, production of immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodwhich can wedge between gut epithelial cells, ies by B cells. Thus, germ-free mice generate continuously sample bacteria from the lumen reduced amounts of IgA as compared to mice with intestinal flora, and have decreased numbers of circulating B and T lymphocytes. MoreBacterial Contributions to Gut Adaptive over, introducing only a single commensal bacImmunity terial species does not restore proper development, Formation of anatomical structures, including Peyer’s suggesting that a diverse repertoire of bacterial patches, which harbor developing B and T cells species and antigens is necessary to drive full Expansion of germinal center reactions involving B and T cells in Peyer’s patches development of intestinal immunity. Increased IgA production by intestinal B cells Recent work by Andrew MacPherson and Generation of antibody diversity (in rabbits) Therese Uhr, of the Institute of Experimental Expansion of intraepithelial lymphocyte populations Immunology in Zurich, Switzerland, has pro(␣TCR-bearing) vided new insights into how commensal bacteria Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 / ASM News Y 81 and present their products to developing gut lymphocytes, thereby inducing B cells to synthesize IgA antibodies that specifically bind to commensal antigens. Such antibodies are ultimately secreted into the gut lumen and are likely critically important in keeping commensal bacteria from crossing into host tissues where they could cause damage. In addition, stimulating IgA production may also help to keep the adaptive immune system poised to deal rapidly with any invading pathogens. Katherine Knight and her collaborators at Loyola University in Chicago, Ill., have shown that in rabbits as in mice, commensal bacteria help drive the formation of lymphoid structures such as Peyer’s patches. Furthermore, although humans and mice generate primary antibody diversity using mechanisms that are independent of microbial colonization, her research reveals that rabbits require intestinal bacteria to generate a diverse antibody repertoire. Thus, for rabbits the intestinal microflora not only appear to play a role in forming the tissues in which intestinal lymphocytes develop but also may influence the ability of the gut immune system to mount a successful immune response. Confirming Cebra’s findings, Knight and her colleagues find that a diverse consortium of bacterial species is required to fully promote immune system development. In addition to providing critical signals for the development of Peyer’s patch-derived lymphocytes, commensal bacteria also influence the recruitment of IELs to the intestinal surface, where they integrate among epithelial cells lining small intestinal villi. Over the past decade, a number of labs have shown that germ-free mice have 10-fold fewer IELs that bear T cell receptors consisting of an ␣ and  chain than do mice carrying commensal bacteria. When germ-free mice become colonized, these IEL numbers increase dramatically. In contrast, IELs that have T cell receptors (TCR) consisting of a ␥ and ␦ chain are unaltered in germ-free mice, strongly suggesting that this IEL population carries out functions that are distinct from ␣TCR-bearing IELs. Commensal Bacteria and the Emergence of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Modern Western societies place a strong emphasis on cleanliness and hygiene. The wide avail- 82 Y ASM News / Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 ability of antibiotics and antibacterial products promotes a nearly antiseptic existence, cleansed of unwanted interactions with the microbial world. However, Western countries are also increasingly afflicted with several immune disorders, such as allergies, that are virtually nonexistent in nonindustrialized nations where access to antibiotics is far more limited. Agnes Wold of Göteborg University in Sweden has proposed that excessive hygiene and antibiotic use, and their accompanying effects on the normal gut flora, might help to explain the rise of immune disorders such as allergy in heavily industrialized regions such as North America and Europe. Originally proposed in 1989 by epidemiologist David Strachan of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, this idea is known as the “hygiene hypothesis.” Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of immune disorders in which the gut is chronically inflamed. Those who suffer from IBDs experience a range of symptoms, including severe diarrhea, abdominal cramps, fever, and rectal bleeding. Most people experience IBD as a painful recurring condition with alternating periods of remission and exacerbation. Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for IBD. Although the causes of IBDs are poorly understood, these disorders are thought to stem from an overly harsh, gut-damaging immune response to the commensal microflora. IBDs and allergies are thus similar in that both are characterized by inappropriate immune responses to otherwise harmless environmental antigens. Epidemiologists have found that IBDs, like allergies, are found mainly in North America and Europe. IBDs currently affect more than 1 in 1,000 individuals in the United States. Moreover, the incidence of IBDs has risen dramatically in North America and Europe over the past 50 years. Although genetics plays a role in IBDs, many investigators have invoked the hygiene hypothesis to explain the increasing prevalence of these diseases. The idea is that exposure to key microbes, particularly during childhood, may be critical for directing the maturing gut immune system to develop tolerance to commensal flora. Disrupting the interactions between commensal bacteria and intestinal immune cells by exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics or excessively clean environments may compromise the development of normal, measured immune responses to commensal gut bacteria. Outlook We are beginning to appreciate more fully the extent to which commensal microbes contribute to human biology. In our nutrient-rich society, we may no longer rely on the metabolic contributions of our prokaryotic cohorts for survival. However, the rise of immunologic diseases such as IBDs underscores the fact that we have intricate, co-evolved relationships with our microbial populations, and that these interactions are likely essential for the normal, healthy development of our immune systems. Building a truly comprehensive understanding of human biology will thus entail developing a detailed molecular picture of our interactions with our commensal microbial populations. Such a picture must include a better grasp of the composition of these populations, how these microbial societies communicate with host cells, and precisely how microbial signals shape the intestinal immune system. This challenge calls for a multidisciplinary line of attack, blending expertise and experimental approaches from fields such as microbial ecology, developmental biology, and immunology. Meeting this challenge will undoubtedly also yield new insights about the consequences of broad-spectrum antibiotic use and its impact on intestinal immunity. By fully elucidating microbial contributions to intestinal immunity, we will be better equipped to harness the power of our bacterial allies in maintaining our health. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful to our colleagues Cassie Behrendt, Anisa Ismail, and Cecilia Whitham for many helpful discussions. Work in the Hooper lab is supported by grants from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America and from the Burroughs-Wellcome Foundation (Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences to L.V.H.). SUGGESTED READING Bandeira, A., T. Mota-Santos, S. Itohara, S. Degermann, C. Heusser, S. Tonegawa, and A. Coutinho. 1990. Localization of ␥␦ T cells to the intestinal epithelium is independent of normal microbial colonization. J. Exp. Med. 172:239 –244. Hooper, L.V. 2004. Bacterial contributions to mammalian gut development. Trends Microbiol. 12:129 –134. Jiang, H. Q., M. C. Thurnheer, A. W. Zuercher, N. V. Boiko, N. A. Bos, and J. J. Cebra. 2003. Interactions of commensal gut microbes with subsets of B- and T-cells in the murine host. Vaccine 22:805– 811. Loftus, E. V., Jr. 2004. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology 126:1504 –1517. Macpherson, A. J., and N. L. Harris. 2004. Interactions between commensal intestinal bacteria and the immune system. Nature Rev. Immunol. 4:478 – 485. Mowat, A. M. 2003. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nature Rev. Immunol. 3:331–341. Rhee, K., P. Sethupathi, A. Driks, D. K. Lanning, and K. L. Knight. 2004. Role of commensal bacteria in development of gut-associated lymphoid tissues and preimmune antibody repertoire. J. Immunol. 172:1118 –1124. Suau, A., R. Bonnet, M. Sutren, J. J. Godon, G. R. Gibson, M. D. Collins, and J. Dore. 1999. Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4799 – 4807. Wostmann, B. S., C. Larkin, A. Moriarty, and E. Bruckner-Kardoss. 1983. Dietary intake, energy metabolism, and excretory losses of adult male germfree Wistar rats. Lab. Anim. Sci. 33:46 –50. Volume 71, Number 2, 2005 / ASM News Y 83