* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Read More - Prudent Management Associates

Short (finance) wikipedia , lookup

Stock trader wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Hedge (finance) wikipedia , lookup

Fixed-income attribution wikipedia , lookup

Interbank lending market wikipedia , lookup

Currency intervention wikipedia , lookup

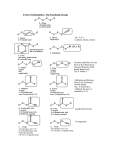

Partner Talk® September 2015 Bond Prices in Turmoil Marshall E. Blume, Ph.D. [email protected] As the markets worried about “COF”---China, Oil, and the Federal Reserve, the S&P 500 declined 5.8 percent in the week ending August 21, the worst weekly decline since a 6.5 percent drop in September 2011 and by Monday of the following week was in correction territory—down ten percent from the prior high. August was not a good month for stocks---the worst month since May 2012. The press attributed this fall to the weakening Chinese economy and its impact on the global economy. To cap this off, oil prices continued to be volatile and the Federal Reserve is expected to begin to raise short-term interest rates this year, although that may take place later in the year given the recent turmoil in the stock market and world economies. The press further reported that there was a “flight to safety”, which means investors turned to government bonds. The closing yield on 10-year government bonds fell to around two percent. On Saturday, August 22, just after the fall in stock prices, the Wall Street Journal carried an article with the headline “Investors Flock to Treasury Bonds,” suggesting that the reduction in the yield (and increase in price, as prices of bonds move inversely to yield) of 10-year government bonds was due to investors selling stocks and buying these bonds. Of course, that cannot be the case. For every seller of a stock, there has to be a buyer of that stock, and for every buyer of a bond, there has to be a seller of that bond. Investors cannot all sell stock and buy bonds. Rather, this piece will argue that the drop in the yield on 10-year government bonds is due to changes in expectations of future interest rates and the premia investors expect to receive as compensation for bearing additional risk. It will end with a discussion of how trading communicates these changes. 1735 Market Street • Philadelphia, PA 19103-7598 • phone 215-994-1062 • fax 215-994-1064 www.prudentmanagement.com Let us begin with a case study set in a world of certainty, where everyone knows both current and future interest rates. Now let’s focus on an investor who wants to invest for two years. He has two choices: (a) buy a one-year bond and roll it over at the end of the first year into another one-year bond, or (b) buy a two-year bond. He is indifferent between the two choices if both produce the same result. If the two choices did not produce the same result, the investor would only choose the one with the best result and prices would adjust until the two choices produced the same result. This is a fundamental principle of economics: Two identical goods in the same market must sell at the same price. To illustrate with some hypothetical numbers, say the interest rate for the coming year is 1.0 percent and the interest rate the following year is 3.0 percent. An investment of one hundred dollars in the roll-over strategy will return $1.00 in the first year and $3.00 in the second year for a total of $4.00 over the two years. If we ignore compounding effects, the two-year bond must also return $4.00 over the two years to be equivalent. Since the coupon on a two-year bond is the same every year, the yield on the two-year bond must be 2.0 percent per year—an average of the interest rates of the roll-over strategy. This bond pays $2.00 the first year and $2.00 the second year, for a total return of $4.00. The rub in this example is that it assumes that future interest rates are known with certainty. In reality, future interests rate are not known. The risk is that future interest rates could be greater or less than anticipated. To continue the two-year bond example, investors will require a yield of more than 2.0 percent per year to compensate for this risk, say 2.2 percent. This additional return of 0.2 percent is the risk premium. In assessing the yield for a two-year bond or any multi-year bond, investors will consider their estimate of future interest rates and then add on a premium to compensate for the risk that future interest rates do not evolve as anticipated. As the maturity of a bond increases, there is a greater risk that actual future interest rates will diverge from those anticipated and thus risk premia will generally be larger. Now, let’s look at the actual yield curve for today and for comparison purposes yield curves ten years ago and twenty years ago. Three Yield Curves 1995 2005 Current 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 30 yr 20 yr 10 yr 7 yr 5 yr 3 yr 2 yr 1 yr 3 non 0 Across all maturities, yields have decreased over the last twenty years. Economists debate the reasons for this trend. A common explanation is that there is an abundance of available worldwide cash to fund capital needs. Further, advances in technology have made capital investment more efficient, so that less capital is required today to support the same level of GDP growth as in the past. In comparison to 2005, the reductions in current yields are most pronounced at the shorter end of the yield curve. This is consistent with the Federal Reserves’ intent to keep short-term interest rates close to zero. The FED’s Quantitative Easing program, which ended last October, was an attempt to hold long-term rates down as well. The yield curves for 1995 and 2005 are consistent with the hypothesis that investors projected that the yields on shorter-term bonds would persist into the future and that the yields of mid- and longerterm bonds should be slightly greater than these projections by small risk premia. The current yield curve is not consistent with this hypothesis. Rather, it is consistent with the hypothesis that investors are forecasting that the near-zero yields of short-term bonds will not persist and that these yields will return to higher levels in the future. Still, the yields on 10-year Treasuries fell from 2.20 percent to 2.05 percent during the week ending August 21. This is a big change – the prices of these bonds rose by over seven percent. Since the news during that week was not great, it is quite reasonable that many investors might have concluded that the FED would not increase short-term interest rates as fast as previously thought. Many might also have concluded that stocks were riskier than before. These motivated sellers of stocks would flood the market with sell orders. Remember, every transaction must have a buyer and a seller. Buyers of stocks would see the market glut and therefore drop the price they were willing to pay. Similarly, motivated buyers of Treasury bonds would flood the market with buy orders. Again, sellers of Treasuries would raise their prices in the face of increased demand. It is through this mechanism that market expectations become incorporated into market prices. Sometimes, the effects of new information are obvious to most investors and prices can adjust very rapidly and with minimal volume. At other times, the effects are not obvious with the result that the process of incorporating new information into prices can take longer and can be messy. But in the end, it is market expectations for the future and required risk premia that determine market prices, not irrational traders. When the FED finally does raise short-term interest rates, the primary tool that it will use is increases in the Federal Fund Rate, which is the overnight rate at which banks borrow amongst themselves. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York manages this rate to stay within a range that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) sets. The current range is from 0 to 0.25 percent or 25 basis points. When the FOMC raises this rate, it is likely that the new range will be from 25 to 50 basis points—an increase of 25 basis points. The FED may also raise the rate that it pays on bank reserves. The impact on the banking sector of a 25 basis point increase in borrowing cost would not be great. Even in the unlikely case that this increase would apply to the 11.4 trillion dollars of total liabilities of all banks, the additional annual interest would be only 34.5 billion dollars. Of course, the banks will try to pass this increase along to its borrowers and such increases would then filter through the entire economy. Perhaps, the additional burden of a FOMC rate increase of 25 basis points as it filters through the economy might be more than 34.5 billion dollars, but even so, this amount is small in an economy of over 17 trillion dollars. The big impact however will be on changes in expectations of future increases and the effect of these changes on bond prices. If the market has correctly incorporated such future increases into current bond prices, the effect on longer-term bonds could be minimal. If, however, future increases turn out to be greater than expected, the prices of longer term bonds would drop; conversely, if future increases turn out to be less than expected, the prices of longer term bonds would rise. The current prices of bonds (and stocks as well) reflect future expectations and required risk premia. When expectations and risk premia change, prices will change. These unexpected changes in prices constitute risks. And it is these risks of unexpected changes in prices across asset classes that are key inputs into PMAs proprietary risk-controlled asset allocation model.