* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Abstract

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Marfan syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Turner syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Infective endocarditis wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

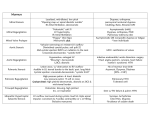

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

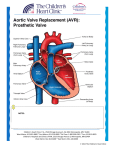

RN Copyright © Medical Economics Publishing Co., Inc. Volume 64(1) January 2001 pp 58-64 Aortic valve replacement [CE Articles] BAPTISTE, MARIA M. RN, MSN, APN,C Section Editor(s): Vernarec, Emil Abstract From hospital to home care, patients receiving prosthetic valves benefit from nurses who understand their condition and know the essentials for avoiding complications of the procedure- and the anticoagulant therapy they may be on for a lifetime. FIGURE Symptomatic aortic valve dysfunction has an ominous endpoint: heart failure. Replacing the damaged valve before the patient reaches that stage is a lifesaving intervention. Figure. No caption available. [Help with image viewing] Many of these patients, however, will need anticoagulation therapy for the rest of their lives to prevent thrombus formation. Anticoagulant therapy itself poses a risk of major bleeding. The key to minimizing both risks is patient adherence to medication, diet, and medical follow-up. Their importance can't be overemphasized. This article reviews the causes and clinical manifestations of aortic valve dysfunction, highlights key points on managing patients who receive valve replacement, and describes how nurses-from hospital to office to home carecan promote the best outcomes by educating patients in their care. When aortic valves malfunction Aortic valve dysfunction usually results from one of two major conditions: aortic stenosis, in which the orifice of the aortic valve narrows and can't open completely, or aortic regurgitation, in which the leaflets of the aortic valve cannot close completely. A healthy aortic valve opens during systole to allow oxygenated blood into systemic circulation and closes during diastole to prevent the backflow of blood into the left ventricle. But if the aortic valve is stenotic, blood flow is obstructed and the heart must work harder to maintain adequate circulation. This leads to a decrease in stroke volume-the amount of blood that is ejected with each beat. To compensate for the decrease, ventricular systolic pressure increases to push the volume of blood into the circulation. The strain on the left ventricle gradually leads to hypertrophy, then to diastolic dysfunction as the atrium meets resistance when it tries to fill the stiff, thickened left ventricle, and, eventually, to congestive heart failure. Aortic stenosis can lead to sudden cardiac death. In aortic regurgitation (sometimes called aortic insufficiency), the stroke volume increases to compensate for the volume of blood leaking back into the left ventricle. This added work causes the heart to enlarge and the left ventricle to dilate, making the heart's pumping action less effective. The stroke volume falls, resulting in hypotension and syncope as a result of decreased cardiac output. The heart becomes congested, causing peripheral and pulmonary edema. The end result: The heart can no longer meet the cardiovascular and oxygenation needs of the body. The most common cause of stenosis is calcification of the aortic leaflets, particularly in patients older than 60 years of age.1 In patients up to age 30, aortic stenosis usually results from an abnormal congenital bicuspid or tricuspid aortic valve. The cause of stenosis in patients between the ages of 40 and 60 is usually rheumatic fever, damage to the heart's connective tissue as a complication of a group A streptococcal upper respiratory infection, or calcification of a congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Aortic regurgitation, on the other hand, is usually a result of rheumatic fever, endocarditis, or a congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Another possible cause is aortic root dilation associated with Marfan's syndrome, rheumatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or syphilis.2 Clinical manifestations of aortic valve disease If symptomatic, patients with aortic valve disease present with chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness, and syncope as a result of diminished blood flow to the brain. The signs and symptoms that distinguish aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation are listed in the box at right. Box 1. Signs and symptoms [Help with image viewing] These patients require immediate assessment of their airway, circulation, and mental status function, and they need to be treated clinically until a definitive diagnosis is made and other diseases are ruled out. The patient history should include description of the chest pain and related symptoms, the frequency and duration of the episodes, what activity precipitates the symptoms, and which interventions alleviate them. The standard tests for diagnosing aortic valve dysfunction include electrocardiogram, two-dimensional echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, and chest X-ray.1 In patients with aortic stenosis, the EKG would reveal signs of left ventricular hypertrophy and ST-T wave changes consistent with left ventricular strain. The 2-D echocardiogram will show leaflet thickening, movement restriction, left ventricular hypertrophy, and an increase in pressure gradient (the speed at which blood is ejected from a narrowing valve). Cardiac catheterization is performed to measure pulmonary artery pressures and cardiac output. Chest X-ray may reveal a normal to enlarged heart, a calcified aortic valve, and dilation of the aorta, depending on the severity of the disease.1 In patients with aortic regurgitation, the EKG typically shows a left ventricular hypertrophic pattern-indicated by exaggerated R waves and prolonged QRS duration-and the chest X-ray shows an enlarged left ventricle. The echocardiogram would reveal the presence of valvular disease and may identify the cause of the regurgitant valve. Like aortic stenosis, cardiac catheterization is done to assess the severity of disease. Managing patients with valve dysfunction Patients with aortic stenosis who are asymptomatic are treated with prophylactic antibiotics and given serial echocardiograms every six to 12 months.3 Serial echocardiograms serve as a guide for appropriate surgical intervention. Stenosis patients should be taught to recognize the signs and symptoms of cardiac decompensation-a stage at which the heart is unable to provide adequate blood circulation. The symptoms include dyspnea, shortness of breath, decreased exercise tolerance, chest pain, and episodes of syncope or near syncope. The use of beta-blockers, diuretics, nitrates, and ACE inhibitors in these patients should be used with caution because such medications may further decrease cardiac output.4 Patients with previously undiagnosed aortic stenosis who present with advanced or symptomatic disease require aortic valve replacement. Both mechanical and biologic tissue valves (bioprosthetics) are available. Without valve replacement, the mortality rate for those with congestive heart failure or those who have had a syncopal episode is 50% over two to three years.1 Poor surgical candidates may undergo percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty to reopen the stenotic valve, which provides short-term relief until they are stable enough for replacement. The management of patients with chronic aortic regurgitation consists of prophylactic treatment with antibiotics, reduction of ventricular afterload with vasodilators such as nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia), and serial echocardiograms every six to 12 months.1 Patients with chronic regurgitation should have a valve replacement before they develop left ventricular dysfunction, and before the heart's ejection fraction falls below 55%. Valve replacement is also indicated for symptomatic patients with an ejection fraction greater than 55%.1 Patients with acute aortic regurgitation as a result of endocarditis are likely to be in an advanced state of heart failure, since a compensatory mechanism for the newly regurgitant valve would not have developed yet. These patients frequently arrive at the ED with severe shortness of breath, tachycardia, and decreased cardiac output. If surgery is indicated, the patient should be treated with antibiotics for at least 48 hours before-hand and may need to be started on nitroprusside sodium (Nitropress) to decrease preload and afterload.4 Avoiding complications after valve replacement Complications of replacing the aortic valve include rejection of the prosthesis, early and late prosthetic endocarditis, mechanical valve malfunction, and hemolytic anemia. For patients with suspected prosthetic valve endocarditis, a surgical consult is imperative. Replacing the infected valve while the patient is on antibiotic therapy has been shown to decrease mortality.5 Early prosthetic endocarditis occurs within 40 to 60 days of valve replacement. It is usually caused by staphylococci, streptococci, or enterococci. The mortality rate ranges from 20% - 70%.1 Signs and symptoms include fever, a new and previously undiagnosed heart murmur, signs of heart failure, and development of thrombus or embolism. IV antibiotic therapy with vancomycin hydrochloride (Vancocin) and gentamicin sulfate (Garamycin) is the standard treatment.6 However, both vancomycin and gentamicin can have toxic effects on the kidneys and the nerves that affect hearing and balance (ototoxicity). Clinicians should therefore know the patient's baseline renal function and monitor blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels daily, as well as the antibiotics' peak and trough levels. Tell patients to notify staff of tinnitus. Late prosthetic endocarditis has signs and symptoms similar to those of early infection but occurs more than 60 days after surgery. It is usually due to infection from staphylococci, streptococci, fungi, or gram-negative bacterial organisms. Bacterial infections are treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. If the infection is caused by staphylococci susceptible to methicillin sodium (Staphcillin), nafcillin sodium (Unipen) may be used in place of vancomycin. Infections caused by candida or aspergillus require IV antifungal treatment with amphotericin B (Fungizone) with or without fluconazole (Diflucan).6 Preventing thrombosis Valvular disease and subsequent valve replacement put the patient at risk for the development of what's known as Virchow's triad: stasis of blood flow, tissue damage, and increased hypercoagulability, which contribute to the formation of clots. To the body, mechanical or prosthetic valves are foreign materials susceptible to fibrin and platelet aggregation; suture material and damage to the endothelium also are factors. For this reason, patients require anticoagulation therapy, initially with heparin and then long-term with warfarin sodium (Coumadin).7 IV heparin is administered immediately following surgery to minimize the risk of thrombus formation. An initial bolus of 80 units/kg followed by an infusion of 18 units /kg/hour has been found to be most effective.8 The patient's activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) should be measured every six hours after the start of the infusion and the dose adjusted as needed, until an APTT of 46 - 70 seconds is achieved. This is followed by daily APTT measurement while the patient remains on heparin. The patient should be monitored for signs of internal bleeding by testing stool guaiac, hematocrit, and platelet levels.9 Look also for increased bruising, hematuria, and tarry stools. Patients on heparin should be told not to use razors, hard toothbrushes, and sharp items. Patients are also started on oral warfarin as early as a day after surgery to minimize the formation of clots. Warfarin works by blocking the enzymatic reduction of vitamin K. This action, in turn, reduces the quantity of circulating coagulation factors by 30% - 50%, and also reduces the activity of each factor by 10% - 14%.7 Precautions are needed with warfarin therapy Patients who have received bioprosthetic valves and who do not have atrial fibrillation or other comorbidities usually require 12 weeks of warfarin therapy. Life-long therapy is required for those who receive a mechanical valve and for patients who have atrial fibrillation or other conditions that could promote clot formation.10 Even with anticoagulation therapy, patients have up to a 2% risk of a thromboembolic event, and up to a 7% risk of bleeding within the first days after surgery.11 Monitoring is critical, since too low a level of anticoagulation for even a brief period of time can result in the formation of a clot on the prosthetic valve, which may break away when warfarin levels are increased to a therapeutic range.7 Monitoring the blood is especially important during the first three months after valve replacement, when anticoagulation control is difficult to manage.12 Warfarin therapy is monitored by measuring prothrombin time (PT). Initially, testing should take place every week to ensure that therapeutic levels have been achieved, and then every one to two months and as needed if there have been changes in diet or episodes of bleeding. The standard measure of PT is the internationalized normalization ratio (INR). According to the American College of Chest Physicians, the recommended therapeutic INR range for patients with mechanical prosthetic valves is between 2.5 and 3.5.13 The optimal range for INR, however, remains controversial. One retrospective study found that patients on anticoagulation therapy who suffered a stroke had an average INR of 2.8, well within that therapeutic range.13 A second study found that bleeding increased at an INR greater than 2.5.14 Other research suggests that an INR as low as 2.0 to 3.0 provides protection against clot formation, with less risk of bleeding.10 For these reasons, the therapeutic INR range should be individualized according to the type of mechanical replacement, the presence of other conditions such as atrial fibrillation, the patient's age, and his history of thrombus formation and stroke. In addition to anticoagulation therapy, some patients are given antiplatelet therapy with either aspirin or dipyridamole (Persantine), especially those with co-existing cardiac comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation or previous thrombus formation.10 But adding an antiplatelet agent may increase the risk of bleeding. Other prescription and over-the-counter medications affect warfarin levels and can therefore increase or decrease warfarin's anticoagulant effects. (See the box on page 61.) So caution and monitoring are essential if any new medications are added or dosages of existing medications changed-including OTC medications. Box 2. Commonly used drugs that increase warfarin activity [Help with image viewing] That's one of the reasons why safe and effective anticoagulant therapy calls for aggressive patient education about the value and the risks of a lifelong regimen following valve replacement. The box at left suggests key points to emphasize when counseling patients. Following through with vigilant monitoring, continuous assessment, and effective patient education is the key to helping these patients reduce their risk of hemorrhage or a debilitating, lifethreatening thromboembolic event. Box 3. Anticoagulation therapy: Get patients involved at the start [Help with image viewing] REFERENCES 1. LeDoux, D. (2000). Acquired valvular heart disease. In S. L. Woods, E. S. Froelicher, & S. U. Motzer (Eds.), Cardiac nursing (pp. 699-718). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Context Link] 2. Massie, B. M., & Amidon, T. M. (1998). Heart in L. M. Tierney, Jr., S. J. McPhee, & M. A. Papadakis (Eds.), Current medical diagnosis and treatment (pp. 333-429). Stamford. CT: Appleton & Lange. [Context Link] 3. Carabello, B. A. (1997). Timing of valve replacement in aortic stenosis: Moving closer to perfection. Circulation, 95(9), 2260. [Medline Link] [Context Link] 4. Logan, P., Ruddy-Stein, Y. A., & Staudenmayer, C. B. (1999). Principles and practice for the acute care nurse practitioner (pp. 641-671). Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange. [Context Link] 5. John, M. D., Hibberd, J., et al. (1998). Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic valve endocarditis: Optimal management and risk factors for death. Clinical Infectious Disease, 26(9), 1302. [Context Link] 6. Gilbert, D., Moellering, R. C., & Sande, M. (1999). The Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy (29th ed.), (p. 22). Vienna, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc. [Context Link] 7. Tiede, D. J., Nishimura, R. A., et al. (1998). Modern management of prosthetic valve replacement. Mayo Clin. Proc., 73(7), 665. [Medline Link] [BIOSIS Previews Link] [Context Link] 8. Ferri, F. F. (1998). Practical guide to care of the medical patient (pp. 922-923). St. Louis: Mosby. [Context Link] 9. Gahart, B. L., & Nazareno, A. R. (1999). 1999 intravenous medications (pp. 446-450). St. Louis: Mosby. [Context Link] 10. Turpie, A. G. (1997). Safer anticoagulation therapy after heart valve replacement: Recommendations for less intense regimens. Postgrad. Med., 101(3), 85. [Medline Link] [CINAHL Link] [Context Link] 11. Cannegieter, S. C., Torn, M., & Rosendaal, F. R. (1999). Oral anticoagulant treatment in patients with mechanical heart valves: How to reduce the risk of thromboembolic and bleeding complications. J. Intern. Med., 245(4), 369. [Medline Link] [BIOSIS Previews Link] [Context Link] 12. Speight, J., & Cooper, G. L. (1997). Anticoagulant control in the first three months after mechanical heart valve replacement. Internstional Journal of Clinical Practice, 51(7), 427. [Context Link] 13. Bussey, H. I., & Lyons, R. M. (1998). Controversies in antithrombotic therapy for patients with mechanical heart valves. Pharmacotherapy, 18(3), 45. [Medline Link] [Context Link] 14. Milano, A., Guglielmi, C., et al. (1998). Valve-related complications in elderly patients with biological and mechanical aortic valves. Ann. Thorac. Surg., 66(6 Suppl), S82. [Context Link] Continuing Education Test #570: "Aortic valve replacement" OBJECTIVES After reading the article you should be able to: 1. Compare and contrast the clinical manifestations of aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation. 2. Compare and contrast the management of aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation. 3. Develop a plan of care for the patient with aortic valve replacement. Circle the one best answer for each question below. Transfer your answers to the card that follows page 84. Save this sheet to compare your answers with the explanations you'll receive. Or, take the test online at www.rnweb.com . 1. Patients who have aortic valve replacement should be told to control intake of vitamin K because it: a. Has an additive effect with warfarin. b. Counteracts the effects of warfarin. c. Increases the risk of hemorrhage. d. Impairs the liver's ability to clear warfarin from the body. 2. The most common cause of aortic stenosis in adults older than 60 years of age is: a. Rheumatic fever. b. Congestive heart failure. c. Calcification of aortic leaflets. d. Abnormal congenital bicuspid aortic valve. 3. Which statement is NOT true about aortic regurgitation? a. It can lead to sudden cardiac death. b. It can be a result of endocarditis. c. Peripheral and pulmonary edema result from aortic regurgitation. d. The leaflets of the aortic valve can't close completely. 4. Standard testing for diagnosing aortic valve dysfunction includes: a. Cardiac catheterization. b. CT scan. c. Complete blood count. d. Tilt table test. 5. Which of the following is NOT usually seen on the chest X-ray of a patient with aortic stenosis? a. A calcified aortic valve. b. A normal to enlarged heart. c. An enlarged left ventricle. d. Dilation of the aorta. 6. Patients with aortic stenosis who are asymptomatic are: a. Told to decrease salt intake. b. Given an annual EKG. c. Scheduled for valve replacement. d. Treated with prophylactic antibiotics. 7. Which is NOT a complication of aortic valve replacement? a. Hemolytic anemia. b. Congestive heart failure. c. Rejection of the prosthesis. d. Early and late prosthetic endocarditis. 8. Diuretics must be used cautiously in the patient with asymptomatic aortic stenosis because these medications: a. Decrease cardiac output. b. May cause dehydration. c. Result in electrolyte depletion. d. Cause wide fluctuations in blood pressure. 9. The management of patients with chronic aortic regurgitation includes all of the following EXCEPT: a. Angioplasty. b. Vasodilators. c. Prophylactic antibiotics. d. Serial echocardiograms. 10. Patients with chronic aortic regurgitation should have valve replacement before: a. Congestive heart failure develops. b. Preload and afterload are increased. c. The ejection fraction falls below 55%. d. Right ventricular dysfunction develops. 11. Early prosthetic endocarditis usually occurs within how many days after valve replacement? a. 10 to 14 days. b. 21 to 28 days. c. 40 to 60 days. d. 90 to 120 days. 12. Patients receiving gentamicin sulfate (Garamycin) for early prosthetic endocarditis should be closely monitored for: a. Hyperglycemia. b. Tinnitus. c. Drug rash. d. Elevated liver enzymes. 13. Patients who have aortic valve replacement initially receive anticoagulation with heparin and then are given: a. Aspirin. b. Vitamin K. c. Warfarin sodium (Coumadin). d. No further medication. 14. Patients on anticoagulation therapy following aortic valve replacement are at what risk for a thromboembolic event? a. Up to 2%. b. 3% - 5%. c. 7% - 10%. d. 12% - 15%. 15. Blood monitoring is especially important for the client after aortic valve replacement for the first: a. Month. b. Three months. c. Six months. d. Year. 16. The recommended therapeutic international normalization ratio (INR) range for patients with mechanical prosthetic valves is between: a. 1.5 and 2.0. b. 2.5 and 3.5. c. 4.5 and 5.5. d. 6.0 and 7.0. 17. All of the following drugs have a major effect on increasing warfarin activity EXCEPT: a. Cimetidine (Tagamet). b. Clofibrate (Atromid-S). c. Ketoconazole (Nizoral). d. Rifampin (Rifadin). 18. Patients who are symptomatic from aortic valvular disease present with: a. Cough. b. Chest pain. c. Peripheral edema. d. Orthostatic hypotension. Credit will be granted for this unit through January 2003. It was prepared by Nancy Clarkson, BS, MEd, RNC, and Anne Robin Waldman, RN,C, MSN, AOCN. Approved for Texas type I credit. Iowa Provider #191. KEY WORDS: anticoagulant therapy; aortic stenosis; aortic regurgitation; cardiovascular procedures; valve replacement