* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Sunnis and The Shiites - Sheila T. Harty, Editor, Writer, Speaker

International reactions to Fitna wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Sources of sharia wikipedia , lookup

Islamofascism wikipedia , lookup

Succession to Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Mormonism wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Imamah (Shia) wikipedia , lookup

Islam and violence wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Islamism wikipedia , lookup

Islamic ethics wikipedia , lookup

Islamic–Jewish relations wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Iran wikipedia , lookup

Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Sikhism wikipedia , lookup

Islamic democracy wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Somalia wikipedia , lookup

War against Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic missionary activity wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Bangladesh wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Islam and other religions wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Twelver Shia Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

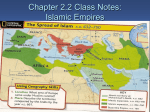

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup

Sunnis and Shiites: Islam’s Schism a theological essay by Sheila T. Harty My interest in Islam dates to 1960 when my military father was stationed in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The gifts and letters he sent home were a window on another world. In the 60s, I lost track of my college boyfriend because he had became a Muslim and changed his name to Mohammed. In the 70s, I studied Islam in graduate school. My professor was a Sufi mystic from Zanzibar. For most Americans, news of conflicts between Sunni & Shiite Muslims falls on deaf Judeo-Christian ears. We don’t understand the difference between Sunnis and Shiites. Then there’s Sufis. How come they all have two syllable names beginning with S? We can’t distinguish these words far less the beliefs. I can’t provide an analysis of the current conflicts. For that, you’ll need to read scholars in the field. I can, however, provide the origin of the Shiite schism from Sunni Islam and a history of the conflict, which will at least provide a foundation to better understand what you hear on the evening news. T o understand the Sunnis and the Shiites as two sects of Islam would be misleading. The name Sunni comes from the Arabic word sunnah, which refers to the traditions of the Prophet; that is, the teachings, sayings, and doings of Muhammed. 1 Sunni, then, are Muslims who follow the orthodox tradition. They constitute 85 to 90 percent of Muslims worldwide. Yet they are not just the majority; Sunni Muslims are the base of Islam. The Shiites are a break-away sect from orthodox Islam. The schism occurred about two generations after the Islamic community was established in Medina, Saudi Arabia. At only 10 to 15 percent worldwide, Shiites are centralized in Iran and Iraq, also in Pakistan and Indonesia, as well as in Lebanon, Yemen, Azerbijan, and Bahrain. Although they are a majority in Iraq, they were a suppressed majority under Sadaam Husain, who was Sunni in name only (and, for the record, Osama bin Laden is also Sunni, as most Saudis are). The schism that produced the Shiite sect was a conflict over succession after Muhammed died. The Arabic word Shi’a means “partisans”; the Shiites were Partisans of Ali, the cousin of Muhammed who was also his son-in-law. Many thought he should have succeeded Muhammed as head of the Islamic community. Ali and his son Hussain are the key figures in Shiite history. The death of Muhammed in 632—only 10 years after the Islamic community was established 2 —was the first great crisis of the Islamic community, a sort of constitutional crisis. 3 Neither Muhammed nor the Qu’ran had provided for succession. 4 Muhammed’s first wife had died as had their only son; Muhammad’s successive wives bore him no children. Nor had he created a council of tribal leaders who might exercise authority in his absence. THE 1ST SUCCESSOR—ABU BAKR U pon Muhammed’s death, a privy council of three companions chose a successor among themselves. They chose Abu Bakr, Muhammed’s father-in-law, who was respected for his piety. He was given The ENDNOTES reflect a reliance on two respected but Western scholars: Bernard Lewis, Department of Near East Studies, Princeton University, and Karen Armstrong, 1999 winner of the Muslim Public Affairs Council Media Award. I have tried to balance these Western sources with research and reading of Arab and Muslim scholars, specifically: Dr. Salwa al-Amd, Department of Near East Studies, Lebanese University; Muhammad Jawad Chirri, founder/director, Islamic Center of America, Dearborn, Michigan; Dr. Muhammad Hanif, Department of Education, University of Louisville, Kentucky; Albert Hourani, author and scholar whose last academic position was reader in History of the Modern Middle East at Oxford; Rashid Ismail Khalidi, director of the Middle East Institute at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs; Dr. Abdullah Muhammad Khouj, director and chief imam of the Islamic Centre of Washington, D.C.; Dr. Mounah A. Khouri, Department of Arabic Language & Literature, University of California, Berkeley; Dr. Mohamed al-Saeed Abdul Mo’men, Department of Iranian Studies, Ain Shams University, Cairo; Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Department of Islamic Studies, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.; Fazlur Rahman, scholar of Persian and Islamic philosophy memorialized by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at University of Chicago; Sheikh Mahmood Shaltoot, head of the School of Theology at Al Azhar University in Cairo; Allamah Tabatabai, scholar of Shariah law, Islamic jurisprudence, mathematics, and philosophy at Qum, Iran; Hussam Tamam, editor of the Cultural Page Arabic Section of IslamOnline.net and expert on political Islam. S.T. Harty The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 2 the title caliph or “deputy” of the Prophet. The choice of Abu Bakr was an indication that merit would be the basis of leadership within the Islamic community, not heredity, which is not particularly practical not in a polygamous society. 5 The role of caliph was neither a priest nor a theologian. Abu Bakr did not claim authority to interpret revelation or arbitrate disagreement on matters of faith, leaving that authority in the Qur’an and in the sunnah of the Prophet. Mohammad’s cousin Ali had many supporters who thought he should have been successor. Ali was not only related to the Prophet by blood but also by marriage to Muhammed’s daughter, Fatima. Ali was also the first male convert to Islamsecond only to Muhammed’s wife Khadijah. But Ali was only 30. Arab respect for age favored Abu Bakr. The role was political with government and military power. By the time of Muhammed’s death, almost all Arab tribes had joined the Islamic Confederacy as converted Muslims. 6 Through Islam, Muhammed had brought unity to the fiercely independent Arab tribes. His death put this feat in jeopardy. Abu Bakr’s first task was countering the refusal of the Arab tribes to recognize the succession.7 The death of Muhammed terminated the tribes’ political contract with him; they felt in no way bound to Abu Bakr as they had taken no part in his election.8 As a result, the tribes suspended both monetary tribute and treaty relations; to reestablish both, Abu Bakr had to make new treaties with those who would and subjugate by military force those who wouldn’t. 9 Two years later, Abu Bakr died. THE 2ND SUCCESSOR--UMAR O n the death of Abu Bakr, Umar (one of the three privy council members) was nominated without serious opposition to succeed as caliph. Umar imposed order. The energies that the tribes had previously expended in raiding each other, which was now prohibited under Islam, had to be diverted. 10 Umar set them upon nonMuslim communities in neighboring countries. Compared with previous barbarian invasions, the organized Arab forces imposed some advantages: for one, Muslims were tolerant of Christians and Jews. 11 Thus, unity was preserved while enhancing the caliph’s authority and gaining territory. Greatly expanding the Islamic empire, Umar remained caliph for ten years. Then, he was murdered in a private vengeance. 12 As Umar lay dying, he appointed a council of six most likely candidates for succession and told them to choose among themselves. 13 Ali was offered the caliphate on condition that he abide by the precedents set by Abu Bakr. Ali refused and I have found no information as to why. So Uthman was chosen as the third caliph. THE 3RD SUCCESSOR--UTHMAN U thman was a member of a leading family in Mecca. The city’s urban wealth had created an aristocracy whose style contrasted with the nomadic life of most Arabs. 14 Thus, Uthman’s appointment represented a victory of the ruling merchant class who had more readily accepted the profits of the new religion then its Prophet. 15 Uthman soon fell under the influence of the Meccans and appointed many to high positions. 16 This nepotism brought him resentment. 17 Uthman also alienated the rich families of Medina, Muhammed’s capital, who still considered themselves closest to the Prophet. 18 Uthman alienated his soldiers as well, who only a decade earlier had been nomads in the desert. 19 Inevitably perhaps, Uthman was assassinated by his own Arab soldiers, 20 which included the son of Abu Bakr. 21 This mutiny against Uthman reflected a pre-Islamic tendency of Arabs toward government by consent. The nomadic view held private judgment as supreme. Obedience to authority was regarded as voluntary; since Uthman failed to inspire it, they felt free to withhold it. 22 The murder of Uthman was a turning point in Islamic history. 23 Most Arab tribes that had joined the Islamic Confederacy had little interest in Muhammed’s religion. 24 Yet, the slaying of a caliph by Muslims S.T. Harty The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 3 set a precedent that weakened the religious prestige of the caliphate as well as the bond of moral unity among Muslims, which was a major achievement of Muhammed’s. 25 THE 4TH SUCCESSOR--ALI li’s role in Uthman’s death is unclear. 26 He had opposed the policies of both Umar and Uthman, 27 who had emphasized central authority. Although he seemed not to bear any direct responsibility for the murder, Ali's failure to use his prestige to prevent it gave his enemies ammunition. 28 Nevertheless, having been passed over three times, Ali was the obvious candidate to succeed Uthman. Indeed, Ali was acclaimed the new caliph. A Ali had grown up with Muhammed’s household and promoted the same ideals; he was considered an inspiring military leader and a compassionate ruler. 29 He had the support of the families of Medina as well as the nomadic tribes, especially those in Iraq. 30 Nevertheless, Muhammed’s favorite wife, Aisha, the daughter of Abu Bakr, 31 along with her kinsmen, attacked Ali for not punishing Uthman’s murderers. 32 Ali’s supporters insisted that Uthman deserved death because he had not ruled justly according to the Quranic ideal. 33 Ali could not disown his supporters, so he took refuge among them in Iraq where Ali made his capital in Kufa. 34 Ali and his soldiers defeated the rebels at what became known as the Battle of the Camel, because Aisha astride her camel rode with her troops but watched the battle from afar. 35 Still, Ali did not condemn Uthman’s assassination, so his rule was not secure. Ali had also not been accepted in Syria, whose governor was Muawiyyah, successor to his uncle Uthman as the head of the Meccan clan. 36 Muawiyyah demanded vengeance in accord with Arab custom, so the Syrian army and Ali’s army confronted each other. 37 Both sides knew such conflicts were contrary to the Muhammed’s mission to promote unity among the tribes, so they tried to negotiate but failed. Supposedly, Muawiyyah’s soldiers then put copies of the Qu’ran on the tips of their spears and called on neutral Muslims to arbitrate according to the word of God. 38 The arbitration went against Ali and Muawiyyah deposed him. 39 Some of Ali’s more radical supporters refused to accept the arbitration. 40 They felt that Ali had compromised and that the spirit of the Qu’ran had been betrayed. These Kharajites, which means “seceders,” established themselves as an independent—and extremist—minority that now posed a separate threat. 41 Indeed, two years later, Ali was assassinated by a Kharajite. But a pattern had been set. 42 From time to time, Muslims who protested some behavior of the ruling caliph would retreat from the community and call upon all true Muslims to join with them in a struggle or jihad for higher Islamic standards. 43 These protests were often over questions of leadership. Should the leader be the most pious, as Kharajites believed? 44 Or a direct descendent of Muhammed, as Shiites believed? 45 Or from the ruling dynasty in order to maintain unity, as Sunnis believed. 46 THE 5TH SUCCESSOR—MUAWIYYAH—OR WAS IT HUSEIN? T hose who remained loyal to Ali in Iraq acclaimed his son Hasan as caliph, but Hasan deferred the caliphate to Muawiyyah for a financial settlement and then retired to Medina with no further involvement in politics. 47 Muawiyyah soon hailed himself caliph from his capital in Damascus, Syria. 48 Muawiyyah ruled for 19 years and restored unity to the empire through efficient administration over the provinces. 49 The most important province was Iraq where his bastard son Ziyad was governor. 50 Even in the 7th century, Iraq was the most difficult and turbulent of the provinces. 51 As Muawiyyah approached his death, he wanted to stabilize the empire by regulating succession. 52 The only precedent from Islamic history was election or civil war. 53 Hereditary succession was still foreign to Arabs. 54 Yet, to secure the empire, he departed from Arab tradition and arranged that his other son Yazid would become the next caliph. 55 S.T. Harty The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 4 THE MARTYRDOM OF HUSEIN he protest against Yazid as caliph was immediate. 56 Yazid’s misfortune was that the harsh rule of his stepbrother Ziyad in Iraq caused a popular uprising among those who were backing Ali’s second son Husain as the next caliph. 57 To join these supporters in Iraq, Husain and a small band of followers with their wives and children set out from Medina. His supporters, meanwhile, intimidated by the Syrians, withdrew their support. Nevertheless, Husain continued toward Iraq, thinking that the Prophet’s family on the march would remind others of Islamic ideals. 58 T On the plain of Karbala outside Kufah in Iraq, the Syrian troops surrounded Husain, his family, and his followers and massacred them all. The murder of Muhammed’s grandson by the army of the ruling caliph was another turning point in Islamic history and the instigating event of the Shiite sect. Husain’s murder is celebrated to this day in Iraq with extreme fervor, including bloody flagellation. After the death of Husain, his descendents lived secluded devout lives in Medina. 59 His supporters were not so pacific. THE TURNING POINT T he dramatic martyrdom of Husain, the hereditary claimant to the caliphate, galvanized Shiites as a political party. 60 They opposed the rule of the caliphs, who were becoming absolute monarchs, which devout Muslims considered unIslamic. 61 They believed that Islamic principles of a just society were more fully preserved in Muhammed’s family who alone should rule. The murderous injustice to Husain became the Shiite focus. For Shiites, Husain is eternal; miracles were ascribed to him even before his birth. 62 Shiism accrued messianic overtones of martyrdom and sacrifice, betrayal and persecution. 63 The saga of the martyrs is the potent core of the Shiite faith. 64 Thus, Shiites regard opposition to tyranny and injustice as a religious duty. The Shiite transfer of Husain and Karbala from history to ideology to legend may be understood from the Shiites’ minority position in Muslim society. 65 By remembering an event of extreme injustice, the ideology of martyrdom helps them maintain solidarity against the dominance of the Sunnis. 66 To Sunni Muslims, support for succession of the caliphs under Ali was the chief offense of the Shiites, because it repudiated the first three caliphs, who were the most revered companions of Mohammad. 67 Still, significant theological differences evolved between Sunnis and Shiites. Shiites amended the traditional call to prayer: “God is great. There is only one God. Muhammad is the messenger of God,” to which the Shiites added “and Ali is the friend of God.” 68 Shiites call their leader “imam,” not caliph, and ascribe miraculous spiritual power to the imam in addition to political power. One extreme Shiite sect even considers the imam divine, 69 which is more than Mohammad even claimed for himself. This enhanced importance of the imam in Shiism is another offense against orthodox Sunnis who believe that no intercession is needed between God and man. 70 Another element of discord between Sunnis and Shiites was over the fifth of the spoils of war, which was traditionally allocated to Muhammed. Sunnis did not consider this inherited by Muhammed’s descendants. 71 Shiites, however, believed that the right to the fifth as a tithe was still due their imam, who could empower deputies to collect it. Such financial support has enabled a powerful Shiite network to evolve independent of government, which has led to clerical rule. 72 The evolution of the imam as an infallible hierarchical spiritual authority is suggestive of Roman Catholicism; whereas, Sunni Islam more closely resembles the independent churches of American Protestantism. 73 THE FIVERS, SEVENERS, AND TWELVERS A s Islam spread, diverse elements merged with Muslim culture, and theology became less orthodox. Wealthy Arabs disposed vast sums of money, which created a new underclass of nonArabs Muslim. 74 S.T. Harty The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 5 Their opposition to these Arab aristocrats, who were Sunni, found religious expression among the Shiites. 75 Thus, Shiism became further entrenched as an opposition sect to Sunnism. 76 The schism of the Shiites from the Sunnis fragmented the political and theological authority of Islam. The Protestant Reformation might be a useful, though imperfect, analogy. The shift of the capital to Damascus from Medina was another loss to orthodox Islam. 77 Ali’s transfer of his capital from Medina to Kufa brought Shiism support from local Iraqis. 78 Many of the more extreme Shiites were converts. 79 Ironically, they brought religious ideas to Shiism from their Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian heritage.80 A branch of Shiism, known as the Fivers, diverged from other Shiites upon the death of the 4th imam in the 8th century. 81 Today, the Fivers—also known as the Zaydis—are the most moderate Shiites, closest to the Sunnis. 82 The country of Yemen is predominantly Zaydi Muslims. Another branch of Shiites, known as the Seveners, believed that Ali’s descendents ended with Ismail, the 7th imam. 83 Seveners, also called Ismailis, believed that faith was worthless unless combined with political activism. 84 In fact, the Assassins were a 12th century sect of Seveners in Iran during a time of extreme militancy against unjust regimes. The hereditary line of the Aga Kahn is also from a branch of Ismailis, the Nizaris. The dominant branch of Shiites and the major branch in Iraq is known as the Twelvers. This breakaway sect originated in the 9th century when the ruling caliph placed the ruling imam under house arrest, wanting no descendent of Muhammed to threaten his rule. 85 When the 11th imam died unmarried, the son he was alleged to have had with a concubine was said to have gone into hiding as a child. Twelve-Imam Shiites claim that this 12th imam was “occulted” (or miraculously concealed by God) and would return to inaugurate an era of peace and justice and take vengeance on the enemies of God. 86 The significance of such an interpretation is obvious; otherwise, the line of Muhammed through Ali and Fatima would be extinct. 87 Shiism, however, developed an integral problem in basing leadership on heredity. A hereditary line could encounter impotence or infertility? Arguably, the disappearance of the twelfth imam masks lack of progeny from the eleventh. Furthermore, no set protocol exists for how to implement the rule of God in the absence of a temporary sovereign. Into this vacuum, ambitious senior clerics arose. However, the myth of the Hidden Imam, rather than a literal belief, was a mystical doctrine, symbolizing the impossibility of implementing religious principles in the real world. 88 Indeed, by the 9th and 10th centuries, militant Shiites were leading armed revolts, far evolved from their original piety as a spiritual elite. 89 UNITY DESPITE SECTARIAN CONFLICTS T hese sectarian differences had varying implications for the nature of government. Some branches of Shiisms 90 withdrew from Islamic society, rejecting the rule of unjust government, and lived under their own interpretation of religious law. 91 However, Twelvers and Ismailis wanted—though each in its own way—an authority that could both uphold the law and maintain order. 92 In my research and reading, I ran across an online Fatwa Bank where the question was asked: “Is Shi’ah part of Islam?” A group of muftis 93 replied: “not everything that goes under the name of Shi’ah is considered Islamic...the Shi’ah have belief and dogma that we condemn as heresy but this doesn’t make them nonMuslim.” 94 Paradoxically, within Islam, holding different beliefs is acceptable. Beliefs and doctrines are not as important in Islam as in Christianity. 95 In 1959, the head of Al-Azhar University in Cairo issued a fatwa, clarifying that “Islam does not require a Muslim to follow a particular school of thought.” 96 Like Judaism, Islam is a religion that requires people to live in a certain way—orthopraxy rather than orthodoxy. 97 Anyone who performs the five pillars of Islam 98 is a Muslim, as both Sunnis and Shiites do. 99 What draws these diverse sects and branches S.T. Harty Page 6 The Sunnis and the Shiites together is their reverence for the Prophet Muhammed, the Qur’an, the Sunnah, the Hadiths, 100 the Shar’iah, 101 and respect for the first four “rightly guided caliphs.” 102 Nevertheless, the Shiites have developed distinctions that justify their existence apart from the majority. As sectarians, they use religion as a mobilizing tool and brandish their version of history as a defensive weapon. 103 So Shiism, which began and failed as a political party over succession to the caliphate, eventually found expression and endurance as a religious sect. 104 However, for the integrity of Islam, one must note that the existence of sects contradicts the Qur’an: “And be ye not among those who join gods with Allah—those who split up their religion and become mere sects—each party rejoicing in that which is with itself!” 105 Ma sha Allah! © Copyright, Sheila Harty, 2011 Sheila Harty is a published and award-winning writer with a BA and MA in Theology. Her major was in Catholicism, her minor in Islam, and her thesis in scriptural Judaism. Harty employed her theology degrees in the political arena as “applied ethics,” working for 20 years in Washington DC as a public interest policy advocate, including ten years with Ralph Nader. On sabbatical from Nader, she taught “Business Ethics” at University College Cork, Ireland. In DC, she also worked for U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the World Bank, the United Nations University, the Congressional Budget Office, and the American Assn for the Advancement of Science. She was a consultant with the Centre for Applied Studies in International Negotiations in Geneva, the National Adult Education Assn in Dublin, and the International Organization of Consumers Unions in The Hague. Her first book, Hucksters in the Classroom, won the 1980 George Orwell Award for Honesty & Clarity in Public Language. She moved to St. Augustine, Florida, in 1996 to care for her aging parents, where she also works as a freelance writer and editor. She can be reached by e-mail at [email protected]. Her website is http:www.sheila-t-harty.com S.T. Harty The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 7 ENDNOTES 1 Dr. Abdullah Muhammad Khouj, Islam: Its Meaning, Objectives, and Legislative System (Arlington VA: Saudi Arabian Television in the USA, 1994), pg. 198-199. 2 The hijra or migration from Mecca to Medina is the starting point of the Islamic calendar. 3 Bernard Lewis, The Arabs in History (New York NY: Harper, 1966), pg. 50. 4 Ibid. 5 Muhammad Hanif, “Islam: Sunnis and Shiites,” Social Education (National Council of the Social Studies, 1994), pg. 339-344. 6 Karen Armstrong, Islam (New York NY: Modern Library, 2000), pg. 23. 7 Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples (New York NY: Time-Warner Books, 1991), pg. 23. See also, Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 52. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 27. 11 Hourani, A History, pg. 25. 12 Ibid. 13 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 59. 14 Mounah A. Khouri, “Literature,” quoted in The Genius of Arab Civilization: Source of Renaissance, 2nd edition (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1983), pg. 25. 15 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 59. 16 Ibid. 17 Ibid. 18 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 32. 19 Ibid. 20 Ibid., pg. 33. 21 Cyril Glasse, ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam (San Francisco CA: Harper & Row, 1989), pg. 457. 22 Ibid. 22 Ibid. 23 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 61. 24 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 26. 25 Lewis, Op. Cit., pg. 61. 26 Armstrong, Op. Cit., pg. 33. 27 Ibid. 28 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 60. 29 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 33. 30 Ibid. 31 Naila Minai, Women in Islam: Tradition and Transition in the Middle East (New York NY: Seaview Books, 1981), pg. 18. 32 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 33. 33 Ibid. 34 Ibid., pg. 34. 35 Ibid. 36 Ibid. 37 “If anyone is slain wrongfully, we have given his heir authority to demand qisas (retaliation) or to forgive.” Surah 17:33 from The Meaning of the Holy Qur’an by Abdullah Yusif Ali (Beltsville MD: Amana Publications, 1995). 38 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 35. 39 Ibid. 40 Ibid. 41 Ibid. 42 Ibid., pg. 36. 43 Ibid. 44 Ibid., pg. 46. 45 Ibid. 46 Ibid. 47 Ibid. 48 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 63. 49 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 41. 50 Lewis, Op. Cit., pg. 65. 51 Ibid. 52 Ibid., pg. 66. 53 Ibid. 54 Ibid., pg. 50. 55 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 41. 56 Ibid. 57 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 67. 58 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 41. 59 Ibid., pg. 56. 60 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 67. 61 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 52. S.T. Harty 62 The Sunnis and the Shiites Page 8 Dr. Salwa al-Amd, The Imam and Martyr in History and Ideology: Shiite Martyr vs. Sunni Hero (Beirut, Lebanon: Arab Foundation for Studies & Publishing, 2000) quoted in a book review by Hussam Tamam, IslamOnline.net, March 18, 2004, pg. 2. 63 Allamah Tabatabai, Shiite Islam (Albany NY: SUNY Press, 1975), pg. 232. 64 Andrew Cockburn, “Iraq’s Oppressed Majority,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2003, pp. 98-105. 65 Ibid. 66 Ibid. 67 John Alden Williams, ed., Islam: Great Religions of the World (New York NY: Washington Square Press, 1969), pg. 80. 68 Hussein Abdulwaheed Amin, ed., “The Origins of the Sunni/Shia Split in Islam,” IslamForToday.com, 2001. 69 The Nusayris. Fazlur Rahman, Islam (London UK: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1966), pg. 174. 70 Seyyed Hossein Nasr, et al., Shiism: Doctrines, Thought, and Spirituality (Albany NY: SUNY Press, 1988), pg. 75. 71 Dr. Mohamed al-Saeed Abdul Mo’men, “Towards an Understanding of the Shiite Authoritative Sources,” translated by Abdelazim R. Abdelazim, IslamOnline.net, Oct. 9, 2003. 72 Ibid. 73 Amin, “The Origins.” 74 Called Mawali. 75 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 71. 76 Ibid. 77 Lewis, Op. Cit., pg. 64, and Armstrong, Islam, pg. 36. 78 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 71. 79 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 52. 80 Ibid. 81 Ali Zahn al-Abidin, 713 CE. The Fivers follow his son Zayd, instead of his older brother, and take up resistance in Yemen. Glasse, The Concise Encyclopedia, pg. 432. 82 Lewis, The Arabs. 83 Although he had been chosen to succeed, he died before his father the 6th imam. This son who died was not the same 7th imam recognized by the Twelvers and other Shiites, who instead recognized the remaining son of the 6th imam as the succeeding 7th imam. Ibid., pg. 354, and Armstrong, Islam, pp. 69-70. 84 Armstrong, Islam, pp. 69-70. 85 Ibid., pg. 68. 86 Glasse, The Concise Encyclopedia, pg. 156. 87 Amin, “The Origins.” 88 Armstrong, Islam, pg. 68. 89 Ibid., pg. 63. 90 The Ibadis (a schism from the Kharajites) and the Zaydis (the Fivers) as branches of Shiism, Hourani, A History, pg. 62. 91 Ibid. 92 Ibid. 93 A legal expert empowered to make decisions of religious import or fatwas. 94 “Shi’ites and Sunnis: Time for Unity” a fatwa answered by a group of muftis on IslamOnline.net, April 6, 2004. 95 Armstrong, Islam, pp. 65-67. 96 Muhammad Jawad Chirri, quoting Sheikh Mahmood Shaltoot in Inquiries About Islam (Detroit MI: Islamic Center of America, 1986). 97 Ibid. 98 The Five Pillars of Islam are: 1. The declaration of faith (shahadah); 2. prayer five times a day (salah); 3. fasting in the month of Ramadan (sawm); 4. almsgiving (zakah); and 5. pilgrimage to Mecca (haj). 99 Armstrong, Islam, pp. 65-67. 100 The tradition or accounts of the actions or words of the Prophet Muhammed. 101 The canonical law of Islam as prescribed by the Qur’an and the Sunnah. 102 “Rashidun” (Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali), Hourani, A History, pg. 25. 103 Rashid Khalidi, “The Emergence of Nationalism in the Modern Middle East,” Fathom: the Search for Learning Online, Fathom Knowledge Network, 2002. 104 Lewis, The Arabs, pg. 71. 105 Surah 30:31-32, Qur’an.