* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Against this Octavian had the wealth of Egypt, two hundred

Executive magistrates of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Early Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Alpine regiments of the Roman army wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

Senatus consultum ultimum wikipedia , lookup

Elections in the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Illyricum (Roman province) wikipedia , lookup

Roman Senate wikipedia , lookup

First secessio plebis wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Late Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Republic wikipedia , lookup

Cursus honorum wikipedia , lookup

Promagistrate wikipedia , lookup

Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Augustus wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

History of the Constitution of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

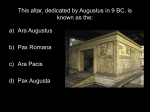

Octavian Returns to Rome Octavian was now, in the year 31 BC, in a position that was utterly unprecedented. Civil war had troubled Rome for nearly twenty years, during which time the machinery of government was thrown into complete disarray. The constitution had been abrogated and ignored so often that it could scarcely be said to exist. The Senate, too, had been alternately ravaged and ignored, and its rights and powers now were largely theoretical. Against this Octavian had the wealth of Egypt, two hundred thousand soldiers, an immense fleet, and complete authority. He was also immensely popular. He conducted himself well, exhibited traditional Roman virtues and values, and was hailed from one end of the Mediterranean to the other as the bringer of peace. After a generation of bloodshed, the ancient equivalent of twenty years of world war, everyone was eager for a peace-giver. Imperator The question on everyone's mind was: what next? What would Octavian do? He was still quite a young man, with the world to command. Would he become a tyrant? A monarch? Octavian was a conservative, traditional Roman. His desire was to preserve the Republic, and he had a genuine respect for it. At the same time, he realized clearly, perhaps more clearly than had his adoptive father, that the Republic was moribund (nearly dead). Something new was in order. His goals were simple: first and foremost, there would be an end to civil war. Octavian from beginning to end insisted on peace and insisted on public order. To affect this, he had to retain control of the military. The Senate and the nobility in general had failed in their duty towards the State in this regard. Sulla had made a mistake in retiring and relinquishing control of the army. Octavian would not make that mistake. With control of the army came control of foreign policy and, by implication, control of state finances. For a time, he simply continued by virtue of the powers he had won as a triumvir. His official title was imperator, by which he had full consular power. As consul, he commanded the army. By other titles he had control over all the provinces and the right to appoint officials at every level of government. His personal wealth was so vast that he was able to pay the salaries of as much as a third of the government out of his own pocket. And so he began arranging the empire. He reduced the number of legions from sixty to twenty-nine, mustering out over 100,000 soldiers and founding numerous colonies. He again packed the Senate, raising its number to 800, nearly all his own creatures. This body proceeded to give the stamp of Republican law to his every act. It is worth noting here how makeshift this was. Octavian had no grand plan, no innovations. To outward appearance, he worked entirely within the system, employing traditional titles and traditional powers; but, in reality, he was inventing a new system. Even though he invented no new offices, never in Rome's history had one man held so many public offices himself. The title imperator would stick, though and the Imperium Romanum is traditionally dated from Actium. Even so, it took a number of years before Octavian hit on the proper combination of titles, and the proper balance between himself and the Senate. Caesar Augustus For the next few years, Octavian ran everything. The business of the city, of the provinces, the army, finance, foreign affairs -- he tended to all of it, or he delegated it to hand-picked men. It was a burden he could not carry indefinitely, and in 27 he made a significant change. In the year 27, Octavian sent notice to the Senate that he wished to speak to that body on a matter of grave importance. Before the assembled senators, he spoke of all he had done for Rome, detailing his accomplishments. He spoke also of how hard was the work, and the toll it was taking on him. Saying he was tired, and that he had already done far more for Rome than any other individual citizen, he resigned all his offices. The senators cried out in dismay. They pleaded with him to reconsider, for the good of the state. A spokesman stepped forward to offer a compromise: Octavian would remain consul, but a second consul would be elected annually, as of old, so that he could share the burden. He would remain proconsul over Italy, Spain, Gaul and Syria, but the Senate would take up responsibility for the rest of the provinces. Octavian accepted these terms. A grateful Senate designated him Augustus, by which name he is generally known in the history books. Augustus means ‘Revered One’ or ‘ the One Worthy of Honor’. He is usually called Octavian until the year 27, and Augustus after that. The likelihood is rather low that Augustus truly walked into the Senate that day intending to retire from public life like Sulla. He had too clear an understanding as to the true state of the Republic. But he really was tired and he really was overworked, and he needed some strategy by which to share power. So he (likely) cooked up this resignation scene, with his own men putting forward the compromise that he desired. The effect of the arrangement of 27 was that the Senate now was able to run domestic affairs. Once again, elections were held for aedile, praetor, quaestor and the other traditional offices of the Republic. The Senate even got to manage some provinces. Augustus retained control over the military, though, and over finances, and over foreign affairs. The Reign of Augustus An important example of Augustus' wisdom in ruling was his treatment of the Senate. He understood that the Senate was, in many respects, the manifestation of the old Republic and that the Republic still exercised a deep pull on the hearts of Romans. Even though many were there by his own patronage, still he allowed them a measure of independence. He would often submit questions to them, asking their advice. He kept them informed of his actions, rather than behaving autocratically. He let them pass legislation and, if the point were minor, even yielded gracefully on laws he did not like. He treated the Senators with respect when speaking with them, and accorded them honors. He never interfered with elections, though he did let his preferences be known in some cases. And he gave the Senate real power: provinces to govern, and two consular armies. Much of the business of running the city itself he likewise gave over to them. By all these concessions he made his imperial rule easier to tolerate. It was possible at least to pretend that the Republic had somehow returned. Everything had changed, of course, and all knew it. But the false front was respectable enough and while there were some conspiracies hatched to restore the Republic, none got very far. The benefits of life under Augustus were too great to throw away lightly, and besides, the memories of the civil wars were still vivid. The Foundations of Imperial Power I have mentioned already, the proconsular power of the emperor. Augustus took other concrete steps to concentrate the key threads of power in his own hands. First and foremost was imperial control of the military. The Senate had two legions, but the emperor had two dozen. Every soldier in every legion swore an oath of allegiance to the emperor personally, as well as to the Republic. Disloyalty to the emperor was treason. Secondly, Augustus had control of the treasury. With the entire nation of Egypt at his command, plus provincial income, the emperor could do as he pleased without ever touching the state treasury. Third, the emperor controlled foreign policy completely. He could declare war, make peace, conclude treaties, all in his own name and binding on the state. Fourth, the emperor controlled the bureaucracy, the civil service of Rome. This was a vast machine of administrators, judges, governors, and tax collectors. Like the soldiers, they swore an oath of personal loyalty. Indeed, Augustus was so rich that he paid the salaries of many of them. With all these under his control, he could well afford to yield this or that office to the Roman nobility. Reforms Augustus also undertook a variety of reforms and acts that benefited the common people of Rome. Most notably, he undertook a vast series of building projects that both gave employment and beautified the city. In the Res Gestae, his own account of his career, he stated that he found Rome a city of wood and left it a city of marble. He ensured water supply to most Roman houses, building or completing aqueducts and a sewage system. He built or renovated many temples. He created a fire department. He ensured at long last a steady supply of wheat to the city and removed the constant fear of famine. And he gave magnificent games, many of which were free to the poor. These and similar acts endeared him to the common people, even as other acts won him the allegiance of the upper classes. Death of Augustus Caesar Augustus died on the 14th of September in the year 14 AD. Three days later, he was declared divine, and shrines for his worship were built. Indeed, such shrines had existed even before his death, but he would not countenance them, so they remained private while he was alive. His elevation to divine status didn't mean people thought the man himself was a god; rather, it was a sign of deep respect and signified that his spirit, his soul, would be taken into the company of the gods. He left some interesting instructions to Tiberius in his will. Three points are notable. First, he recommended that Tiberius restrict the granting of citizenship and the freeing of slaves. Citizenship would be devalued if extended too freely, and slaves were critical to the functioning of the economy (there was, in the early first century, something of a fad of manumission). Second, he said to rely only on men of tried ability. He was recommending against playing favorites, against granting offices to friends and relatives unless they truly were worthy. Finally, and above all, Augustus instructed Tiberius to keep the Empire within the bounds he had set for it. Augustus had been badly shaken by the defeat of Varro at the Teutoburger Wald, and he was certain that further disasters awaited if Rome should become over-extended. It is worth noting that, over the course of the next two centuries, Roman emperors violated each of these three recommendations. The succession went smoothly. There were no revolts, no mass uprising to bring back the Republic. In the first place, few wanted the Republic back. In the second place, Augustus had provided for everything in his will. This system required that the emperor die in old age and with time for planning. That would not always prove to be the case. Read the article the questions thoroughly. and answer 1. What were Octavian’s goals when he returned to Rome? 2. How did he change Rome? 3. What did Octavian tell the Senate he wanted to do in 27 B.C.? What changes were made to his role? 4. What does Augustus mean? 5. How did Augustus handle the Senate? Do you think he did a good job? Why or why not? 6. How was Augustus able to control the empire? 7. What were some reforms Augustus created? 8. What instructions did Augustus leave to Tiberius