* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Marketing strategy and the internet: An organizing framework

Product placement wikipedia , lookup

Food marketing wikipedia , lookup

Viral marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Price discrimination wikipedia , lookup

Multi-level marketing wikipedia , lookup

Service parts pricing wikipedia , lookup

Bayesian inference in marketing wikipedia , lookup

Guerrilla marketing wikipedia , lookup

Planned obsolescence wikipedia , lookup

Market penetration wikipedia , lookup

Direct marketing wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Target audience wikipedia , lookup

Competitive intelligence wikipedia , lookup

Marketing research wikipedia , lookup

Marketing mix modeling wikipedia , lookup

Product lifecycle wikipedia , lookup

Digital marketing wikipedia , lookup

Youth marketing wikipedia , lookup

Neuromarketing wikipedia , lookup

Integrated marketing communications wikipedia , lookup

Segmenting-targeting-positioning wikipedia , lookup

Predictive engineering analytics wikipedia , lookup

First-mover advantage wikipedia , lookup

Street marketing wikipedia , lookup

Darknet market wikipedia , lookup

Multicultural marketing wikipedia , lookup

Resource-based view wikipedia , lookup

Advertising campaign wikipedia , lookup

Target market wikipedia , lookup

Sensory branding wikipedia , lookup

Green marketing wikipedia , lookup

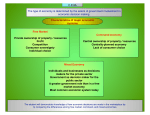

Perfect competition wikipedia , lookup

Pricing strategies wikipedia , lookup

Marketing channel wikipedia , lookup

Product planning wikipedia , lookup