* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download West Nile Virus - Nicholas Kurek`s Portfolio

Influenza A virus wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Chagas disease wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Sexually transmitted infection wikipedia , lookup

2015–16 Zika virus epidemic wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

African trypanosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Ebola virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Infectious mononucleosis wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

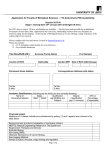

Running head: WEST NILE VIRUS 1 West Nile Virus Nick Kurek Ferris State University WEST NILE VIRUS 2 Abstract West Nile Virus [WNV] is a reemerging disease. It is an emerging disease in the United States where it has spread from an initial appearance in the New York City area in 1999 to become endemic in the continental United States. It is necessary for clinicians and the general population to be aware of WNV. This paper explores WNV. Transmission, clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, means of possible prevention of acquisition, an analysis of current literature, and a look at factors that may actual promote the emergence of WNV will be discussed. The author leaves the reader pondering reality. WEST NILE VIRUS 3 West Nile Virus We live in a dangerous world. A seemingly insignificant thing, such as a mosquito bite, could potentially be fatal and/or have life altering consequences. Mosquitoes, while necessary for the food chain, carry many diseases. West Nile Virus [WNV] is one of them. WNV is technically a reemerging infectious disease. Veenema (2013) defines reemerging as “infections that have been known but demonstrate a marked increase in incidence or geographic range” (p. 430). While WNV is not a new disease globally, it is relatively new in the United States and certainly of concern. Anderson & Harrington (n.d.) inform us that while we have known about the WNV since the late 1930’s, it first appeared in the United States during the summer of 1999 in the New York City area. Kilpatrick, Kramer, Jones, Marra, & Daszak (2006) state “WNV has caused repeated large-scale human epidemics in North America since it was first detected in 1999” (para.1). WNV has spread across the continental United States with cases having been reported in all 48 continental States (Anderson & Harrington, n.d.). The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID] (2010) has WNV in its list of 20 emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2013) informs us that there has been 1.5 million reported WNV infections in the United States since the first in 1999. WNV continues to spread across the country and in Michigan. In its most current report, the Michigan Department of Community Health [MDCH] received 104 reports of WNV from 2007 – 2011 with the highest annual total of 34 cases being reported in 2011 (Michigan Department of Community Health Bureau of Disease Control, Prevention, and Epidemiology Reportable Infectious Diseases in Michigan, 2007–2011, p. 96). WEST NILE VIRUS 4 Transmission What is WNV? The MDCH states “WNV is a single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family (flavivirus)” (Michigan Department of Community Health Bureau of Disease Control, Prevention, and Epidemiology Reportable Infectious Diseases in Michigan, 2007–2011, p. 95). WNV is a zoonotic (spread from animals to humans), vector borne disease. The Virginia Department of Health (2013) informs us that a vector borne disease is “the term commonly used to describe an illness caused by an infectious microbe that is transmitted to people by bloodsucking arthropods (insects or arachnids)”. The CDC (2013) states: Vector-borne diseases are among the most complex of all infectious diseases to prevent and control. Not only is it difficult to predict the habits of mosquitoes, ticks and fleas, but most vector-borne viruses or bacteria infect animals as well as humans. WNV which is primarily a disease of birds, is a good example. WNV is definitely an example of a vector borne disease. In fact, Kilpatrick et al (2006) state “WNV is now the dominant vector-borne disease in North America”. It is important to realize that not every mosquito carries WNV. The MDCH (2007-2011) states “In areas where WNV is actively circulating, less than 1 in 100 mosquitoes will be infected”; however, once a mosquito is infected, it remains infective and can subsequently infect people for its life span (Michigan Department of Community Health Bureau of Disease Control, Prevention, and Epidemiology Reportable Infectious Diseases in Michigan, 2007–2011, p. 95). Unfortunately, like most viruses there can be multiple routes of transmission. WNV is usually acquired from being bitten by an infected mosquito. There have been “a very small WEST NILE VIRUS 5 proportion” of cases where it has been spread from “blood transfusions, organ transplants, exposure in a laboratory setting, and from mother to baby during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding” (CDC, 2013). Clinical Presentation People get bit by mosquitoes all the time. It is very possible to be infected with WNV and not know it. The CDC (2013) states “70-80% of those who become infected with WNV do not develop any symptoms”. This implies that the vast majority of people who are infected may not even realize it and may even potentially transmit it to others. As with most diseases there is an incubation period from infection to manifestation of symptoms. Those who do develop WNV symptoms usually start to feel sick and exhibit symptoms 3 to 14 days after being infected (Goodman & Livingston, 2012). The majority of people who develop WNV symptoms experience a relatively mild form. The CDC (2013) states: About 1 in 5 people who are infected will develop a fever with other symptoms such as headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash. Most people with this type of West Nile virus disease recover completely, but fatigue and weakness can last for weeks or months. While most cases of WNV are relatively mild, there are cases that become severe. Goodman & Livingston (2012) inform us “approximately 1 in 150 infected persons develop severe disease with serious symptoms”. WNV can have lifelong consequences. Murray et al (2010) that “WNV is capable of long-term persistence in patients, particularly in the presence of chronic clinical symptoms” (p.3). WNV may even result in death. The CDC (2013) states: WEST NILE VIRUS 6 Less than 1% of people who are infected will develop a serious neurologic illness such as encephalitis or meningitis (inflammation of the brain or surrounding tissues). The symptoms of neurologic illness can include headache, high fever, neck stiffness, disorientation, coma, tremors, seizures, or paralysis. Serious illness can occur in people of any age. However, people over 60 years of age are at the greatest risk for severe disease. People with certain medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, and people who have received organ transplants, are also at greater risk for serious illness. Recovery from severe disease may take several weeks or months. Some of the neurologic effects may be permanent. About 10 percent of people who develop neurologic infection due to West Nile virus will die. Diagnosis Usually, the WNV mimics flu-like symptoms and passes in a short period of time. Many people do not seek care unless they develop severe symptoms. This is important to note as it may definitely skew the number of cases in that there may be a more wide spread incidence; however, many may simply not be reported due to the mild symptoms experienced. It is when symptoms become severe and progress that people present to clinicians for treatment. An accurate history is an essential part of the assessment. Many of the symptoms previously discussed will be present. In contemplating a differential diagnosis, the CDC (2013) recommends: WNV should be considered in any person with a febrile or acute neurologic illness who has had recent exposure to mosquitoes, blood transfusion, or organ transplantation, especially during the summer months in areas where virus activity has been reported. The WEST NILE VIRUS 7 diagnosis should also be considered in any infant born to a mother infected with WNV during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Unfortunately, some people may not be able to give nor have family available to provide a history. Clinically, the manifestation of WNV may be similar to other viral infections and may not necessarily be readily diagnosed. The CDC (2013) states: Less than 1% of infected persons develop neuroinvasive disease, which typically manifests as meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis. WNV meningitis is clinically indistinguishable from viral meningitis due to other etiologies and typically presents with fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity. WNV encephalitis is a more severe clinical syndrome that usually manifests with fever and altered mental status, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, or movement disorders such as tremor or Parkinsonism. WNV acute flaccid paralysis is usually clinically and pathologically identical to poliovirusassociated poliomyelitis, with damage of anterior horn cells, and may progress to respiratory paralysis requiring mechanical ventilation. WNV poliomyelitis often presents as isolated limb paresis or paralysis and can occur without fever or apparent viral prodrome. WNV-associated Guillain-Barré syndrome and radiculopathy have also been reported and can be distinguished from WNV poliomyelitis by clinical manifestations and electrophysiologic testing. As with many diseases, initial routine blood work may not be specific enough to lead to diagnosis. Specific blood tests provide the definitive diagnosis of WNV. Quest Diagnostics (2012) states: WEST NILE VIRUS 8 The IgM antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (MAC–ELISA) is the most conclusive laboratory method for diagnosis of WNV infection of the CNS. Quest Diagnostics currently offers an IgM MAC–ELISA, an IgG ELISA, and a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for WNV. The methods can be performed using CSF or blood (ie, serum/plasma) samples. A nucleic acid amplification test is also available for donor testing. Treatment There is no cure for WNV. The CDC (2012) states “although various drugs have been evaluated or empirically used for WNV disease, none have shown specific benefit to date”. There is no specific treatment for WNV. Treatment of those infected with WNV is directed at managing symptoms and providing supportive care (Goodman & Livingston, 2012). Prevention While WNV cannot be treated as yet, its spread may be prevented or at least controlled through mosquito management. Even though mosquitoes carry many diseases, they are a necessary member of the food chain and we cannot simply eradicate them. We can attempt to control the mosquito populations and protect ourselves from them. CDC (2012) states: No WNV vaccines are licensed for use in humans. In the absence of a vaccine, prevention of WNV disease depends on community-level mosquito control programs to reduce vector densities, personal protective measures to decrease exposure to infected mosquitoes, and screening of blood and organ donors. Personal protective measures include use of mosquito repellents, wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, and WEST NILE VIRUS 9 limiting outdoor exposure from dusk to dawn. Using air conditioning, installing window and door screens, and reducing peridomestic mosquito breeding sites, can further decrease the risk for WNV exposure. Blood and some organ donations in the United States are screened for WNV infection; health care professionals should remain vigilant for the possible transmission of WNV through blood transfusion or organ transplantation. Any suspected WNV infections temporally associated with blood transfusion or organ transplantation should be reported promptly to the appropriate state health department. It is important to note that in the CDC’s recommendation, the community and each individual are encouraged to take and are provided with measures to enhance their own safety and decrease potential for acquisition. Awareness is essential. We can decrease our chances of acquiring WNV by following the CDC’s advice. Personal protection as outlined by the CDC may not always be followed; however, it is necessary to be cognitive of it especially if we are going to be in areas heavily populated with mosquitoes. Prevention starts with awareness and each individual’s actions or inactions. Veenema (2013) informs us that increases in infectious, vector borne diseases can be attributed to “standing pools of water from increased rainfall which become a rich breeding ground for mosquitoes” (p. 432). Something as simple as maintaining our properties and ensuring that there is not standing water lying for mosquitoes to breed in can make a huge difference. Analysis Upon a rather thorough review of current available literature, it is quite evident that the government and government funded researchers are aware of and concerned with WNV and its potential. WNV has essentially exploded across the United States in a matter of a relatively few WEST NILE VIRUS 10 years. The majority of the sources all drew from the CDC. Many provided the exact same or very similar yet differently worded overviews as well as transmission, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention criteria. Essentially most of the basic information was taken from the CDC and regurgitated in slightly different words. This is understandable as it simply is what it is. Factors that may Promote WNV WNV is a vector-borne disease. Veenema (2013) informs us that the climate changes in the United States as well as the world are affecting and will continue to affect us (chapters 18 & 26). The scary thing is that with global warming and climate changes, there is a high potential for increased incidences and exposures of WNV and other vector-borne viruses and diseases. Kilpatrick, Meola, Moudy, & Kramer (2008) summarized: Both viral evolution and temperature influence the distribution and intensity of transmission of WNV, and provides a model for predicting the impact of temperature and global warming on virus transmission. Conclusion In today’s global society viruses and diseases are not necessarily specific to a particular region as in years past and are becoming increasingly found throughout the world wherever the climate can support them. It is somewhat reassuring that WNV usually is relatively mild in manifestation; however, it can potentially have lifelong consequences and in some cases may even be fatal. We are lucky to have recognized WNV and be aware of what we can do to protect ourselves. There will always be a certain amount of exposure/risk; however, we need to attempt to minimalize it as best we can. WEST NILE VIRUS 11 The fact that most cases of WNV are mild leads one to question the accuracy of data. How many folks have had WNV and simply thought it was the flu? How many folks simply do not go to the doctor? How many clinicians have misdiagnosed mild cases? This is important to note as it definitely skews the number of actual cases. It is totally plausible and most likely that WNV and perhaps even a number of other viruses and diseases are more prevalent and wider spread than previously thought. WEST NILE VIRUS 12 References Anderson, R. R., & Harrington, L. C. (n.d.). West Nile virus. Retrieved from http://entomology.cornell.edu/extension/medent/westnilefs.cfm Bradley, C. A., Gibbs, S. E. J., & Altizer, S. (2008). Urban land use predicts west Nile virus exposure in songbirds. Ecological Applications 18(5): 1083–1092. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/07-0822.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). West Nile virus. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html Goodman, D. M., & Livingston, E. H. (2012). West Nile virus. Journal of American Medical Association. 308(10):1052. http://dx.doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11678 Kilpatrick, A. M., Kramer, L. D., Jones, M. J., Marra, P. P., & Daszak, P. (2006). West nile epidemics in North America are driven by shifts in mosquito feeding behavior []. PloS Biology, 4(4), e82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040082 Kilpatrick, A. M., Meola, M. A., Moudy, R. M., & Kramer, L. D. (2008). Tempature, viral genetics, and the transmission of West Nile virus by culex pipiens mosquitoes. PLoS Pathology, 4(6), e1000092. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000092 Michigan Department of Community Health Bureau of Disease Control, Prevention, and Epidemiology Reportable Infectious Diseases in Michigan 2007–2011: 95-7. Retrieved from: http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/2011_CDEpiProfile_400563_7.pdf WEST NILE VIRUS 13 Murray, K., Walker, C., Harrington, E., Lewis, J. A., McCormick, J., Beasley, D. W., ... FisherHoch, S. (2010). Persistent infection with West Nile virus years after initial infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 201, 2-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/648731 National Institutes of Health. (2012). West Nile virus. Retrieved from: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/westnile/Pages/default.aspx National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2010). Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. Retrieved from: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/emerging/Pages/Default.aspx Quest Diagnostics. (2012). West Nile virus: Detection with serologic and real-time pcr assays. Retrieved from: http://www.questdiagnostics.com/testcenter/testguide.action?dc=CF_WestNileVirus Veenema, T. G. (2013). Disaster Nursing and Emergency Preparedness for Chemical, Biological and Radiological Terrorism and Other Hazards (3rd ed.). New York: Springer Publishing Co. Virginia Department of Health. (2013). Vector-borne disease control. Retrieved from: http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/epidemiology/DEE/Vectorborne/ Wheeler, S. S., Vineyard, M.P., Woods, L.W., & Reisen, W.K. (2012). Dynamics of West Nile virus persistence in house sparrows (Passer domesticus). PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 6(10): e1860. http://dx.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001860