* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Effective Writing

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Antisymmetry wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sloppy identity wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Comparison (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Relative clause wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Determiner phrase wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Vietnamese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Before Entering a Grammar Handbook:

A Guide to the Sentence

I

Most of us worry about correct grammar. And when we write, we

also worry about correct punctuation, such as those pesky commas and

mysterious colons and semicolons. And we are right to worry about them.

Most people judge us not only by the dialect we happen to be speaking but

also by the kinds of errors that they can detect in our speech or writing.

I’m not going to say that I have a pill that if you swallow, the problem

will go away. But my years of teaching English composition have taught me

a thing or two about correct grammar. I want to share what I know with

you. I want to provide access to the rules of correct grammar and

punctuation by making you aware of what a sentence is. I want to show you

the parts of this automobile that we call “a complete sentence.” Once you

learn the meanings of just a few words, you will be able to read a grammar

handbook with comprehension and pleasure.

Here is a complete sentence:

(1) John is a bear.

And here’s another complete sentence:

(2) John kicks a bear.

Actually, what I’ve done here is given you two sentences that contain

a noun, “John,” and its verb (1) “is” and (2) “kicks.” You have to have at

least a noun (or a pronoun) and a verb to make a meaningful statement. We

call that combination of noun-verb the subject and predicate of the sentence.

Every sentence that you write has to contain at least one subject-predicate

combination:

(1) Good people tell few lies.

(2) Honesty is a blessing.

(3) The bigger they are, the harder they fall.

(4) Nothing matters as much as emotion (matters).

(5) A wise choice means that there will be fewer regrets.

I’ve underlined the simple subjects with one line and the simple

predicates with two lines. Now what can I say about these subject-predicate

combinations?

I can say that in each case of a subject-predicate combination

someone or something either is or does something. Please notice that in my

opening examples of a complete sentence I wrote, (1) “John is a bear.” And

then I wrote (2) “John kicks a bear.” The first sentence says that “John”

exists as a bear. In the second sentence, “John” does something: he kicks a

bear. Believe it or not, when you make any statement about our world, all

that you can do is 1. say what someone or something either is or is-like or 2.

state what someone or something does. There are no other choices. Our

world is composed of “things” that act in relationship to other “things.” You

can with a sentence either state what one of these “things” is like or what

any one of these “things” does. As I said, there are no other choices. A

sentence (or rather, a clause—about which later) names a person, place,

thing, or idea and says what that person, place, thing, or idea is or is-like. Or

it names a person, place, thing, or idea and says what he or she or it does or

they do. There are no other choices.

Let’s take a look at the five sentences that I used to illustrate subjectpredicate combinations:

(1) Good people tell few lies.

(2) Honesty is a blessing.

(3) The bigger they are, the harder they fall.

(4) Nothing matters as much as emotion (matters).

(5) A wise choice means that there will be fewer regrets.

At this point let me state what a clause is. A clause is not Santa Claus.

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a predicate and that

can be either a complete sentence or a part of a sentence. When it is or

could be written as a complete sentence, we call it an “independent clause.”

When it’s just a part of another clause, it’s called a “dependent (or

subordinate) clause.”

Sentence (1) is one independent clause. It contains one subjectpredicate combination and makes sense by itself. The subject people in this

case does something: tell.

In sentence (2) Honesty is what is being talked about. Honesty is the

subject of the sentence. But in this case Honesy doesn’t do anything. It is

merely being identified as a “blessing.” It is merely being identified as

existing in a certain way, as a “blessing.” The verb is is called a “state of

being” verb while the verb tell in sentence (1) is called an “action” verb. So

the “state of being” verb tells us what the subject is or is-like while the

“action” verb tells us what the subject does.

“In sentence (3) please notice that there are two subject-predicate

combinations: “they are” and “they fall.” We need at least one independent

clause in order to have a complete sentence. Which of these two clauses,

“The bigger they are” and “the harder they fall” is a complete sentence by

itself? It’s the second one, “the harder they fall.” The first clause, “The

bigger they are” tells how they fall (harder)—they fall harder “The bigger

they are.” There are two clauses in this sentence, and the second clause is

independent while the first clause is dependent. Notice that you can’t

reverse the two clauses and still make sense: “The harder they fall, the

bigger they are.” It’s the clause “The bigger they are” that helps to explain

“the harder they fall” and not the other way around.

In sentence (4) there are two subject-predicate combinations: Nothing

matters and emotion (matters). You’ll notice that the second predicate

“matters” has been written in by me. I would usually simply say, “Nothing

matters as much as emotion.” But the meaning, of course, is that “nothing

matters as much as emotion matters.” The second “matters” is understood to

be there, just as when I write “He’s the man we like,” I mean “He’s the man

whom we like.” The word “whom” (a relative pronoun) has been left out.

Or in another case of something being left out, we write “It’s a nice day.”

The word “It’s” really means “It is.” The letter “i” has been left out and

been replaced by an apostrophe. It’s important to realize that sometimes the

way something is expressed leaves certain parts of the sentence out. Such

constructions have the fancy name of being “elliptical”—as in ellipsis points

(. . .) when a person is showing that something has been left out of a quoted

sentence. Such ellipses occur often in speech:

“Why’d he do that?” (Why did he do that?)

“Don’ know.” (I do not know.)

“You sure?” (Are you sure?)

“Of course! You think I’d lie?” (Of course I am sure! Do you think

that I would lie?)

Now here’s the sentence again: “(4) Nothing matters as much as

emotion (matters).” There are two clauses since there are two subjectpredicate combinations. What are the two clauses? Well, the first one is

simply “Nothing matters” while the second one is “as much as emotion

(matters).” At least one of these clauses has to be independent if we are to

have a complete sentence. Which clause is independent? Which clause

could be read as a sentence by itself? Well, it’s clearly the first one,

“Nothing matters.” I could not write “As much as emotion (matters).” The

words “As much as” make a person wonder how the idea relates to

something else. It doesn’t express a complete independent notion of

somebody or something being something or doing something. But when I

attach it to the first clause, “Nothing matters,” the second clause makes

perfect sense: Under what conditions can one say that “Nothing matters”?

“Nothing matters” or is anywhere near as important as when it is qualified

by emotion. The verb “matters” in “Nothing matters” is being qualified by

the clause “as much as emotion (matters).” Thus the second clause is a

dependent clause. And because it is modifying a predicate (verb), it is an

adverb dependent clause.

The last sentence under consideration, “(5) A wise choice means that

there will be fewer regrets” also contains two subject-predicate

combinations: “choice means” and “regrets will be.” Please notice that the

usual pattern of subject-predicate can be reversed in certain situations, such

as in questions, “Do you dance?” where the helping verb “Do” precedes the

subject “you.” It can be done just for effect, as in the sentence, “In the

basement lurked the little jinn.” And then there is the above situation using

what is called an expletive, “There,” to start the sentence. For instance,

“There’s milk in the refrigerator” or “There are bananas on the table.” In

both these sentences the predicate precedes the subject: ‘s milk (is milk) and

are bananas.

Once again, since there are two subject-predicate combinations, that

means that there are two clauses. Which one of these clauses is

independent? We need at least one independent clause in order to have a

complete sentence. In this case the entire sentence “A wise choice means

that there will be fewer regrets” is the independent clause. Why is this so?

Well, the reason is that the second clause is a noun-clause. It is a whole

clause working as if it were merely a one-word noun. The noun clause is

“that there will be fewer regrets.” It answers the question “what?” to the

independent clause “A wise choice means what?” I could have written, “A

wise choice means security.” Or I could have written “A wise choice means

fewer worries.” The words “security” and “worries” in the examples are

single-word nouns. Please notice that they also answer the question

“what?”: “A wise choice means what? (security); “A wise choice means

what? (fewer worries). “A wise choice means what? (that there will be

fewer regrets). A noun clause is a group of words containing a subject and

predicate and working together as a noun—the name of a person, place,

thing, or idea. Therefore wherever a noun can occur in a sentence, a nounclause can be used in that place.

Before I move on to the nitty-gritty of the specifics of the parts of

speech, phrases, and clauses of a sentence, I also want to mention to you that

grammarians talk of sentences as being simple, compound, complex, and

compound-complex. What does this mean? What grammarians have done

is to look at the number and types of clauses that are found in a given

sentence. If there is only one subject-predicate combination and the clause

makes sense by itself, we say that it is a simple sentence. If there are two or

more independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction or

conjunctions (and, but, or, nor, for, yet, so) or a correlative conjunction or

conjunctions (either . . . or, neither . . .nor, whether . . .or, not only . . .but

also, both . . .and), and there are no dependent clauses, the sentence is called

a compound sentence. Now if the sentence contains one independent clause

and at least one dependent clause (it could have more than one dependent

clause), it is called a complex sentence. And finally there is the last

possibility: the sentence contains at least two independent clauses and at

least one dependent clause (there could be more dependent clauses, just as

there could be more independent clauses). In this case the sentence is called

compound-complex. Here are two examples of each type of sentence (I’m

indicating independent clauses in yellow highlight and dependent clauses in

turquoise highlight. I’ve also underlined simple subjects with one line and

simple predicates with two lines):

simple sentence: (1) Derrick is a simple man.

(2) Derrick holds no grudges.

compound sentence: (1) Wyconnda is the wife, and Derrick is her husband.

(2) A good marriage requires a lot of compromise, and

a good marriage requires mutual tolerance, but above all else a good

marriage requires honesty.

complex sentence: (1) Whenever Derrick stays out late, Wyconnda wants to

know why.

(2) Derrick, who is an honest husband, doesn’t mind

telling her the truth because he is not guilty of infidelity.

compound-complex: (1) Wyconnda likes to shop, but Derrick prefers to stay

at home because for him shopping is boring.

(2) Derrick always makes sure that the house is safe,

and he doesn’t get to bed until he has checked the doors and windows.

The best writers know how to “mix it up.” They do not write a series

of simple sentences, for instance, because the effect is too choppy. They

write simply, that’s true, but they vary the kinds of sentences that they use

because the human mind likes variety even as it likes uniformity. So the

thoughts are presented in a logical manner but conveyed in sentencestructures that keep the reader’s interest fresh.

II

I have already prepared a file to explain the parts of speech, phrases,

and clauses—the components of the automobile that is the English sentence.

But whereas the parts of an automobile are all useful in creating a vehicle

whose primary purpose is transport, the parts of a sentence are all useful

toward conveying information—creating meaningful communication. Once

you have learned the meaning of the parts of speech, of the four types of

phrases, and of the four types of clauses, you will be able to read a good

grammar handbook with ease and comprehension. You will be able to apply

the rules for correct writing to your own writing. You will know when you

have expressed something effectively, and if you have not expressed it

effectively, you will be able to correct what you have written. A knowledge

of correct grammar and punctuation is a powerful asset in a highly literate

and technological society. As I’ve read somewhere or heard it said, even the

most difficult mathematical formulas can be expressed in words. The

problem is that the expression becomes very complicated. Mathematical

symbols are a kind of shorthand to get the idea said in a very economical

way. But a good writer can explain what a given equation means and what it

is meant to achieve. The spoken or written word is immensely useful.

So let me insert this file directly below:

Effective Writing

Table of Contents

Effective Writing ............................................................................................ 7

The Parts of Speech ...................................................................................... 10

Noun/Pronoun and Verb ............................................................................... 11

Adjectives and Adverbs ................................................................................ 13

Prepositions ................................................................................................... 14

Conjunctions ................................................................................................. 15

Prepositional Phrases .................................................................................... 22

Verbals: Participles, Gerunds, and Infinitives .............................................. 27

Clauses .......................................................................................................... 30

Distinguishing between Independent Clauses and Noun Clauses ................ 37

Summary ....................................................................................................... 40

Examples of Effective Writing ..................................................................... 41

Effective Writing

Dear Students,

I’m going to try to explain as best I can what it means to write

effectively. First of all I want to tell you that too many people think that

writing is something as natural as burping. It isn’t. Just because a person

knows how to burp, that person doesn’t in the same way know how to write.

Correct, effective writing requires a knowledge of words, the accepted order

for arranging those words into phrases and clauses, and choosing such

words, phrases, and clauses as most clearly and compellingly communicate

what the writer is actually trying to say. This activity is nothing like burping

until one has learned correct grammar, done a lot of writing, and

experienced life both in the everyday living of it and in the reading about it

by other writers who are competent at what they do. Then the writer can

“burp” with each word. She or he knows the rules inside and out, is entirely

familiar with applying those rules, and experiences few moments when there

is any difficulty in making her or his point as economically yet cogently as

possible. That’s when people say that a person’s art makes the most difficult

things seem easy. Burping is easy. But effective writing isn’t easy until one

has learned to do it according to the rules for clear communication.

Good writers give one a lot of pleasure. They see the world as

objectively as possible, don’t try to make it into something that it isn’t, yet

find all sorts of beautiful data available to their skill to express. Some

writers are especially able at presenting a detailed view of the world of their

senses and intellect, while others have an enormous knack to get at the

feelings that their experiences raise in them. They give the world an

emotional tinge that other people regard as remarkable.

So one can ask, “What exactly is a person doing when she or he writes

effectively?” My answer is simple: the person knows how to put a subject in

front of a predicate and to modify that subject and predicate effectively.

This seems to be no “big” thing:

John is a bear.

John sees a bear.

Please notice that the second sentence could have any number of “action”

verbs in it:

John kicks a bear.

John likes a bear.

John watches a bear.

John feeds a bear.

and so on. By the way, the verb “be,” which has the additional forms, “am,”

“is,” “are,” “was,” “were,” “been,” and “being” –eight forms in total, is a

true state-of-being verb. There are only two others (linking verbs that can

take either a predicate adjective or a predicate noun): “become” and

“remain.” Thus the sentence above, “John is a bear,” which doesn’t express

any action that John is doing, could also convey a state of being if it were

written as follows:

John becomes a bear.

John remains a bear.

The verbs “becomes” and “remains” aren’t expressing an action, as the verbs

“sees,” “kicks,” “likes,” “watches,” and “feeds” express. These two

situations, when somebody or something either is or does something are the

only two things that can happen when a person is trying to communicate

with another person. There are variations, such as those involving different

tenses, voice, and mood, but basically everything comes back to this

premise: a subject either is something or does something.

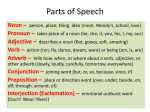

The Parts of Speech

Just as an auto-mechanic has to know what a gasket is, a piston-ring, a

valve, an oil filter, and so forth, in order to work on a car-engine—or a

surgeon has to know what a suture is, and a scalpel, nipper, curette, forceps,

and so forth—a writer has to know what the eight parts of speech are. They

are the units that go into the building of sentences, but even more

importantly, they are the functions that individual words do in sentences, as

well as what phrases and clauses do. Actually, there are only seven parts of

speech—units that go into the construction of a clause or a sentence. The

interjection is merely a word that stands outside of a sentence, such as the

words “Wow!” “Gee!” or “Yay!” for instance. Therefore I will be speaking

only of the seven parts of speech from now on:

Nouns

Pronouns

Verbs

Adjectives

Adverbs

Prepositions

Conjunctions

Please notice that the parts of speech are printed above in four

groupings, and each part of speech is assigned a given color. Nouns and

pronouns are “naming words,” and I have assigned the color red to them.

Verbs are the action words (or the state-of-being verbs), and I have assigned

the color blue to them. Adjectives modify nouns or pronouns, so I have

chosen the color red for them, just as I have for the nouns and pronouns.

Adverbs modify verbs, so, like the verbs, they are blue in color. Finally

there are the “joining” words, the prepositions and conjunctions. I have

assigned the color green to them.

Just as an automobile is meant to transport people and things, a

sentence is meant to convey some information. Each automobile consists of

parts that are meant to facilitate transport. The engine generates power, the

transmission delivers that power to the wheels, the wheels provide the

locomotion, and the body of the automobile houses the passengers and

cargo.

In a sentence, the nouns (or pronouns) are the subjects and objects

under discussion, the verbs tell what those subjects and objects are doing or

being, the adjectives make those subjects and objects more specific so that

the information is more accurate, the adverbs clarify the verbs, indicating the

strength, duration, time, place, and extent of the action. Prepositions join a

noun or pronoun to the rest of the sentence as a modifier (either as an

adjective or an adverb), while the conjunction can join two words, phrases,

or clauses together. And that’s it. These seven units either name somebody

or something, express action or state of being, make clearer which

“somebody” or “something” is under discussion, establish the conditions

under which an action is taking place, or join different words or groups of

words together. Here’s an explanation of the parts of speech, with examples

of how they are used:

Noun/Pronoun and Verb

Nouns and pronouns are “naming” words. They are words that stand

for “somethings” and “somebodies.” A noun is a word that names a person,

place, thing, or idea and always creates a kind of “picture” in the mind. If a

person says the word “table,” the picture that I’m talking about isn’t of a

round or a square table but of a flat surface supported, usually, on legs. One

can pull a chair or chairs up to it and eat from it or place one’s books on it.

A pronoun, on the other hand, doesn’t create a picture in the mind.

Words such as “it,” “he,” “that,” “someone” and so forth indicate a thing or

person, but they don’t create a “picture” in the mind.

Verbs express action or state of being. “Raul kicks the ball.” “Raul is

a man.” Both of these are independent clauses as well as complete

sentences. The verbs (which are also called predicates when they are the

action or state of being that the subject does or is) are indicated in blue.

Verbs are not hard to identify in a clause, especially the action-verbs.

Noun/Pronoun and Verb can create a Clause,

and a clause can be a sentence.

Adjectives and Adverbs

Adjectives=these are words and groups of words that make nouns

clearer: good girl; man on the roof; beautiful flower; a man who loves

baloney.

They answer the general question, “What Kind Of?”

Adverbs=these are words and groups of words that make verbs or other

adverbs or adjectives clearer: spoke loudly; listens with interest; hit the ball

hard; went to the store whenever he could; walked extremely slowly.

They answer the questions, “How?” “When?” “Where?” “Why?” “To

What Degree?” “Under What Conditions?”

Adjectives and Adverbs “fill in” the meaning that the

subject and the predicate express. They make clearer

exactly what kind of “who” or “what” did it and how,

when, where, or why he, she, it, or they did it.

Prepositions

Prepositions are “pointer words” that join nouns or pronouns to the

rest of the clause as adjectives or adverbs. They indicate direction, usually,

such as the prepositions in, into, through, over, down, beyond, above, and

so forth. They also “point” a few other things, less easy to pin down, such as

during, for, except, and so forth. But this one fact is for sure: they are

followed by a noun or pronoun that they link to the rest of the clause as

either an adjective or an adverb. All prepositional phrases work as either

adjectives or adverbs. And by that I mean that the whole phrase, such as “in

that room,” is either an adjective or adverb depending on how it is used in

the clause. It is an adjective in the sentence, “The man in that room is

talking.” But it is an adverb in the sentence, “The man is talking in that

room.” In the first case “in that room” is describing the man, his position in

space, but in the second case, “in that room” is modifying the verb “is

talking,” telling where he is talking.

Here’s a list of prepositions copied from The Bedford Handbook:

about

above

across

after

against

along

among

around

as

at

before

behind

below

beside

besides

between

beyond

but

by

concerning

considering

despite

down

during

except

for

from

in

inside

into

like

near

next

of

off

on

onto

opposite

out

outside

over

past

plus

regarding

respecting

round

since

than

through

throughout

till

to

toward

under

underneath

unlike

until

unto

up

upon

with

within

without

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are actual “joining” words because they truly “join”

either individual words, phrases, or clauses. When they join exactly equal

things, like a teeter-totter, they are either coordinating conjunctions or

correlative conjunctions. When they join unequal units, they are called

subordinating conjunctions.

As I keep telling you, there are only seven coordinating conjunctions:

and, but, or, nor, for, yet, so. They join either two words, two phrases, or

two clauses. Those words, phrases, and clauses have to be of the same kind:

“John and Mary”; “to sing and to dance”; “He likes to dance, and she likes

to sing.”

The correlative conjunctions are “either . . . or”; “neither . . . nor”;

“both . . . and”; “whether . . . or”; “not only . . . but also”—and they work

just like coordinating conjunctions: “Either Mary or Paul will go”; Either to

sing well or to dance well is required”; “Either Mary will bake the cake, or

John will bake the cake.”

The subordinating conjunctions introduce adverb clauses. You know

the most common one which I am always bringing up in class: because.

Here’s a list of them from The Bedford Handbook:

after

although

as

as if

because

before

even though

how

if

in order that

rather than

since

so that

than

that

though

unless

until

when

where

whether

while

why

Here are a few sentences to show them in action:

(1) After he had bought the baloney, he was satisfied.

(2) Although he had bought the baloney, he still wasn’t satisfied.

(3) As he was buying the baloney, his satisfaction increased.

(4) As if buying baloney was all-important, he went to the store.

(5) Because he buys baloney, he doesn’t have money for ham.

Now each of these sentences can be re-cast to put the adverb clause last:

(1b) He was satisfied after he had bought the baloney.

(2b) He still wasn’t satisfied although he had bought the baloney.

(3b) His satisfaction increased as he was buying the baloney.

(4b) He went to the store as if buying baloney was all-important.

(5b) He doesn’t have money for ham because he buys baloney.

Please notice that when the adverb clause introduces the sentence, it is

followed by a comma. But when it concludes the sentence, it is not

separated from the independent clause by a comma.

Expanding a Simple Sentence

I started this document with two simple sentences:

John is a bear.

John sees a bear.

The first sentence has a noun in it, John, and another noun, bear. It

also contains the state-of-being verb is and an indefinite article, a, which is

treated as a weak adjective modifying the noun bear.

The second sentence also contains two nouns, John and bear. But it

contains an action verb, sees, as well as the indefinite article a, which is

serving, as I mentioned above, as a weak adjective modifying the noun bear.

Both of these sentences can be expanded with adjective and adverb

modifiers. These modifiers can be single-words, phrases, or clauses. Let’s

expand the first sentence:

John, who lives caged at Lincoln Park Zoo, is a polar bear.

And then I can expand it some more:

John, who lives caged at Lincoln Park Zoo, is a huge polar bear.

And some more:

John, who lives caged at Lincoln Park Zoo, is a huge polar bear without

much hair.

And:

John, who lives caged at Lincoln Park Zoo, is strangely a huge polar bear

without much hair.

And here is the list of modifiers that I have added to that sentence:

who lives caged at Lincoln Park Zoo is an adjective clause;

polar is a single-word adjective;

huge is a single-word adjective;

without much hair is an adjective prepositional phrase;

strangely is a single-word adverb modifying is.

The second sentence can also be expanded:

John sees a big bear.

And then I can say,

John, who is a student of mine, sees a big bear.

And then further on,

John, who is a student of mine, sees a big, heavy bear.

Further:

John, who is a student of mine, sees a big, heavy polar bear.

And further still:

John, who is a student of mine, sees a big, heavy polar bear who is named

“John.”

And even further still:

John, who is a student of mine, sees a big, heavy polar bear living at the zoo

[who is named “John.”]

And then adverbs can be added:

Because he lives close to the zoo, John, who is a student of mine, often

sees a big, heavy polar bear living at the zoo [who is named “John.”]

And here is the list of modifiers that I have added to the sentence:

big is a single-word adjective;

who is a student of mine is an adjective clause;

heavy is a single-word adjective;

polar is a single-word adjective;

who is named “John” is an adjective clause;

living at the zoo is an adjective participle phrase (which includes an adverb

prepositional phrase “at the zoo” as a part of the participle phrase and

modifying the verb “living”—living where?--“at the zoo”)

Because he lives close to the zoo is an adverb clause modifying the verb

“sees”

often is a single-word adverb modifying the verb “sees”—sees when?—

often sees

Please notice that no matter how a speaker or writer may expand a

sentence with modifiers, the basic core of the clause or sentence remains the

same:

John is bear.

John sees bear.

What that person is doing is attaching modifiers to the nouns and pronouns

that make up the core of the clause or sentence. The modifiers are meant to

give clarity to the basic components. To say, “I drove a car yesterday” is not

as specific as saying “I drove John’s yellow Buick yesterday.” The

adjectives “John’s” and “yellow” and the noun “Buick” have created a much

more vivid and accurate picture of the event.

I have mentioned that modifiers can occur as single words, as phrases,

and as clauses. According to what they are doing inside of a clause, singlewords are identified as being nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs,

prepositions, or conjunctions.

Phrases, which are groups of words that do not contain a subject or a

predicate but are working together to do one job as if they were a single part

of speech, are identified by their structure as well as their function.

According to structure, the most commonly found phrase is the prepositional

phrase, which always works as either an adjective or an adverb. There are

also three verbal phrases: the participle phrase, the gerund phrase, and the

infinitive phrase. The participle phrase is always either an adjective

(usually) or an adverb (rarely). The gerund phrase is always an –ing form of

the verb working as a noun, and the infinitive phrase is always the

preposition to followed by a verb and not a noun or pronoun and working as

either a noun, adjective, or adverb. So “to sing” is an infinitive, but “to

John” is a prepositional phrase.

A clause is a group of words that contains its own subject and

predicate and that is working as either a complete sentence (independent

clause) or as a noun, adjective, or adverb (dependent, or subordinate,

clause). “John is a bear” is both a clause and a sentence. The reason that it

is a clause is that it is a group of words working together and containing a

subject and a predicate, and in this case working as a complete sentence

(independent clause). But if I were to write “Because John is a bear,” I

would still have a clause because the group of words contains a subject

“John” and a predicate “is,” and if I were to use it in a sentence, it would be

working as an adverb. For instance, I could write, “Because John is a bear,

he eats a lot.” You’ll notice that the main idea is “he eats a lot.” That’s an

independent clause because it contains its own subject “he” and the predicate

“eats” and expresses a complete idea. The clause “Because John is a bear”

is a clause, as I have already explained, but it can not be written as a

sentence by itself, so it is not an independent clause. It is a dependent

adverb clause because it is modifying the predicate “eats” in the independent

clause: “Why does he eat a lot?”—“Because John is a bear.” A predicate is

the verb of a clause, and therefore any word or group of words that is

modifying the predicate (verb) must be an adverb because adverbs are words

or groups of words that express how? when? where? why? under what

conditions? to what degree? something happens. Adverbs can also modify

adjectives and adverbs, as in the example “She is a very intelligent young

lady.” The three adjectives are “a,” “intelligent,” and “young.” The adverb

“very” modifies “intelligent.” “How intelligent is she?”—“very.” So the

word “intelligent” is modifying the noun “lady”—What kind of “lady”?—

“intelligent”—but “How intelligent”?—“very.” “Intelligent” is an adjective

modifying a noun, and “very” is an adverb modifying an adjective.

Now to review what I have already said: “What exactly is a person

doing when she or he writes effectively?” My answer is simple: the person

knows how to put a subject in front of a predicate and to modify that subject

and predicate effectively. A sentence has to be made up of at least one

clause (an independent clause), and every clause contains its own subject

and predicate, which means that somebody or something is either being

something or doing something:

John is a bear.

John sees a bear.

Also, a noun, adjective, or adverb can be a single word, a group of words

without a subject and a predicate (a phrase), or a group of words containing

a subject and a predicate (a clause). Let me explain the four kinds of phrases

first, and then the four types of clauses.

Prepositional Phrases

A prepositional phrase, as I mentioned above in the section on the

parts of speech, is introduced by a preposition and ends on either a noun or a

pronoun, called “the object of a preposition.” Thus in the sentence, “Mary

walks her dog in the park,” the prepositional phrase is “in the park.” The

word “in” is the preposition, and the object of the preposition is the noun

“park.” It tells where Mary walks her dog: “in the park.” It is an adverb

prepositional phrase because it is modifying the predicate (verb) “walks.”

Here again is the list of prepositions as copied out of The Bedford

Handbook:

about

above

across

after

against

along

among

around

as

at

before

behind

below

beside

besides

between

beyond

but

by

concerning

considering

despite

down

during

except

for

from

in

inside

into

like

near

next

of

off

on

onto

opposite

out

outside

over

past

plus

regarding

respecting

round

since

than

through

throughout

till

to

toward

under

underneath

unlike

until

unto

up

upon

with

within

without

Just to provide a few examples, I can create prepositional phrases using each

of the first five prepositions listed:

about the bill

above the water

across the river

after the war

against the enemy

Please notice the structure of these phrases: preposition + “the” + noun (or

pronoun). They fit into a clause to modify either some other noun or

pronoun in the clause, or to modify a verb in the clause (or sometimes

another modifier). Thus I can write sentences using each of the

prepositional phrases that I have created above:

1. He called the phone company to inquire about the bill.

2. The ducks swam above the water.

3. The trees across the river looked very green.

4. The peace after the war did not last.

5. Almost all of the troops marched against the enemy.

Please notice that about the bill in the first sentence is an adverb

prepositional phrase modifying the verb “inquire”—how inquire?—about

the bill.

In the second sentence the phrase above the water is also an adverb

prepositional phrase. It modifies the verb “swam”—where swam?—above

the water.

In the third sentence, across the river is an adjective phrase. It is not

modifying a verb. It is saying something about the noun “trees”—which

trees or what kind of trees?—across the river trees.

In the fourth sentence we also see an adjective prepositional phrase.

Which peace are we talking about, or what kind of peace are we talking

about?—after the war peace.

And in the fifth sentence we see another adverb prepositional phrase:

against the enemy. It is an adverb phrase because it modifies a verb and not

a noun: marched where?—against the enemy.

But a prepositional phrase doesn’t have to have only the three

words— the preposition, the adjective “the,” and the object of the

preposition. A prepositional phrase can be made up of only two words, the

preposition and its object, or four or more words. For instance, “Give the

book to John” contains the two-word prepositional phrase “to John,” but the

sentence “He looked into her deep, dark eyes” contains the prepositional

phrase “into her deep, dark eyes.” A prepositional phrase is defined by the

notion that there is a preposition which is linking some noun or pronoun to

the rest of the clause as an adjective or adverb modifier. It doesn’t matter

whether the prepositional phrase contains merely two words or four or more

words. The phrase is meant to modify either a noun (pronoun) or to modify

a verb or another modifier.

Please take a look at this sentence:

The man in the green suit swam in the dirty river.

Notice that the sentence contains two prepositional phrases introduced by

the preposition “in.” The entire two phrases are “in the green suit” and “in

the dirty river.” So by structure these are prepositional phrases—they begin

with a preposition and end on its object. However, as I have mentioned

several times, all prepositional phrases function as either adjectives or

adverbs. They are modifiers. They can make a noun clearer, more specific,

or they can make a verb clearer, more specific. In the example above, for

instance, “in the green suit” is clearly saying something about the man.

Which man or What kind of man?—in the green suit man.

But the phrase “in the dirty river” says something about the verb

(predicate) “swam.” Where swam?—in the dirty river. Since it is

modifying a verb, it is called an adverb prepositional phrase.

Now, to finish up this explanation of prepositional phrases, I’ll take

the last five prepositions from the list out of The Bedford Handbook and

create sentences in which each of the prepositions introduces first an

adjective phrase and then an adverb phrase:

1. The raft up the river moved slowly up the turn.

2. The pen upon the table was used upon occasion.

3. The man with the golden arm spoke with his wife.

4. The soul within his body knew what raged within his heart.

5. A person without enemies lives without excitement.

Please notice that sentences 1, 2, 3, and 5 are composed of only one

independent clause each—which means that they are complete sentences

since there are no other clauses. But sentence number 4 contains two

clauses: the independent clause, which is the entire sentence, but inside of

that independent clause is a noun clause acting as a direct object of the

predicate “knew”—knew what?—“what raged within his heart.” In each

case I have the first prepositional phrase modifying the subject of the clause,

and each second prepositional phrase modifying the predicate (main verb) of

a clause. Thus, in the first sentence, up the river is modifying the noun

“raft” answering the question what kind of? raft—up the river raft. Then up

the turn is modifying the verb “moved”—moved where?—moved up the

turn.

In the second sentence, upon the table is saying something about the

subject (noun) pen, what kind of pen?—upon the table pen. The phrase

upon occasion, on the other hand, is saying something about the verb

“used”—used when?—upon occasion. Since it is a phrase that is modifying

a verb, it is an adverb prepositional phrase.

In the third sentence, with the golden arm is saying something about

the “man”—which man?—with the golden arm man. Since “man” is a

noun, then the phrase which is making it more specific or clearer must be an

adjective phrase. The phrase, with the golden arm, is an adjective

prepositional phrase. But the phrase with his wife is an adverb prepositional

phrase. It is modifying the predicate (main verb) of the clause, “spoke.” As

a result it’s an adverb phrase because it is answering the question how? he

spoke or under what conditions? he spoke. He spoke with his wife.

In the fourth sentence, it’s clear that within his body is saying

something about the subject “soul.” Therefore, since it is modifying a noun,

it must be an adjective prepositional phrase. The phrase, within his heart, on

the other hand, is modifying the verb of the noun clause, “raged.” Where?

raged—raged within his heart.

And then in the fifth sentence, without enemies is saying something

about the noun “person” and is therefore an adjective prepositional phrase

while the phrase “without excitement” says something about how he or she

lives—lives without excitement. The phrase without excitement is therefore

an adverb prepositional phrase because it is modifying a verb.

Finally, you have to realize that a phrase is a group of words without a

subject and a predicate working together as one part of speech. But you

have to remember that a prepositional phrase is composed of at least two

words, and what that means is that each individual word is its own part of

speech, but the words together are also a part of speech. Thus the

prepositional phrase “on the dark water” is an adverb phrase in the sentence

The feather floated on the dark water.

Where did the feather float?—on the dark water. The phrase on the dark

water is an adverb prepositional phrase modifying the verb “floated.” Any

word or group of words that makes a verb clearer is called an adverb. But

what about all the individual words in the phrase “on the dark water”? Well,

“on” is a preposition, “the” is a weak adjective, “dark” is an adjective, and

“water” is a noun. A prepositional phrase begins with a preposition and

ends with its object (either a noun or a pronoun).

Verbals: Participles, Gerunds, and

Infinitives

Today I want to talk about verbal phrases (infinitive phrases, gerund

phrases, and participle phrases). You already have a pretty good idea of

what a prepositional phrase looks like (in the room, to him, by the river,

during the war, at the railroad crossing) and that a prepositional phrase

always functions as an adjective or an adverb. And every prepositional

phrase is found inside of some clause, whether that clause is independent or

not:

Raul kicks the ball into the stands.

“into the stands” is an adverb prepositional phrase telling where he kicks the

ball.

Because Raul kicks the ball in his direction, the goalie must react quickly.

“in his direction” is a prepositional phrase answering the question where?

kicks: “in his direction.” Therefore “in his direction” is modifying the

predicate kicks of the adverb clause “Because Raul kicks the ball in his

direction” and is thus an adverb prepositional phrase. The prepositional

phrase “in his direction” is located inside the adverb clause “Because Raul

kicks the ball in his direction” and not inside the independent clause “the

goalie must react quickly.”

Verbal phrases behave in the same way. They are always related to

other words in the same clause, whether that clause is independent or

dependent (adjective clause, adverb clause, or noun clause). The verbals are

classified according to how they look.

An infinitive is always the preposition to followed by a verb and not a

noun. “To sing” is an infinitive; “to John” is a prepositional phrase.

The gerund is always the –ing form of a verb working as a noun:

Singing is fun.

“Singing” is working as a what? in this sentence, so it is a noun. The noun

always answers the question who? or what?

A participle can have several forms:

singing

sung

having sung

speaking

spoken

having spoken

talking

talked

having talked

and it is always working as a modifier, either as an adjective or an adverb:

The man [speaking in a loud voice] is John.

In this sentence “speaking in a loud voice” is modifying the noun man: what

kind of? man: “speaking in a loud voice” man. The phrase “speaking in a

loud voice” is a participle phrase working as an adjective.

OR

Words [spoken in anger] usually cause hurt feelings.

what kind of? words: “spoken in anger” words. Therefore the phrase

“spoken in anger” is a participle phrase working as an adjective.

John, [having spoken in anger], wished he had thought before

speaking.

What kind of? John: the John “having spoken in anger.” Again this is an

example of a participle phrase working as an adjective. The three forms of

the participle have their own names:

speaking is called the present participle

spoken is called the past participle

having spoken is called the perfect participle

To get back to the infinitive. It also can have several forms:

present infinitive: to walk

perfect infinitive: to have walked

progressive infinitive: to be walking

It doesn’t matter whether it’s walk, have walked, or be walking. If it’s

preceded by the preposition to and is functioning as a noun, adjective, or

adverb, it’s an infinitive.

To walk the dog gives him pleasure.

What? gives him pleasure: “To walk the dog”—“To walk the dog” is an

infinitive phrase working as a noun.

The desire to walk the dog has become a habit.

What kind of? desire has become a habit? The desire “to walk the dog.” In

this case the infinitive phrase “to walk the dog” is working as an adjective

modifying the noun desire: what kind of? desire: “to walk the dog” desire.

He was persuaded by his mother to walk the dog.

How?—under what conditions? persuaded: “to walk the dog.” In this case

the phrase is not clearly answering how? when? where? why? under what

conditions? to what degree? But it is modifying the verb (predicate)

persuaded. The phrase “to walk the dog” in this case cannot be called a

noun or an adjective. It is definitely not answering the questions what? or

what kind of?

This is the lesson for today. Each phrase (prepositional phrase,

infinitive phrase, gerund phrase, and participle phrase) works inside of some

clause as a noun, adjective, or adverb. The gerund phrase is always a noun.

The prepositional phrase and the participle phrase are always working as

either adjectives or adverbs. The infinitive phrase can work as any of those

three: noun, adjective or adverb.

Clauses

It is possible to learn about the four types of clauses. A clause is a

group of words that contains a subject and a predicate. And you already

know what “contains a subject and a predicate” means. It means that a noun

or a pronoun either does something or is something (by the way, I’m

underlining the subject of a clause with one line and the predicate [main

verb] of the clause with two lines):

Raul kicks the ball.

Raul is a man.

Both of the sentences above are also independent clauses. A clause is

independent when it can stand alone as a sentence. Here is another sentence:

John goes to the store because he is hungry.

In the above sentence there are two clauses because there are two subjectverb combinations:

(1) John goes

(2) he is

Notice that in (1) the subject “John” does something, “goes,” and in (2) the

subject “he” is something, “is.” That means the sentence contains two

clauses:

John goes to the store

because he is hungry

In this case only one of the two clauses is independent:

John goes to the store

This clause can be written as a sentence by itself:

John goes to the store.

But “because he is hungry” cannot be written as a sentence by itself:

Because he is hungry.

It is a sentence-fragment. If somebody were to say to you either “Because

he is hungry” or “Because John is hungry,” you would ask, so? More

information is required. This clause is dependent, not independent. And if it

is dependent, then why is that so?

The answer is that a dependent clause is working as a part of speech

with regard to another clause and is not meant to express separate, selfcontained information. It merely adds to the meaning of another clause. A

dependent clause can work as a noun in another clause, it can modify a noun

or pronoun in another clause, or it can modify the verb or some adjective or

adverb in another clause. That’s why grammarians say that there are four

types of clauses:

independent clause

noun clause

adjective clause

adverb clause

Here are examples of each:

Independent Clause: John buys three pounds of baloney.

Noun Clause: Whoever craves tasty fat buys three pounds of baloney.

Adjective Clause: The man who loves tasty fat buys three pounds

of baloney.

Adverb Clause: John buys three pounds of baloney because he loves tasty

fat.

The independent clause can be written as a complete sentence:

John buys three pounds of baloney.

But the noun clause

Whoever craves tasty fat

cannot be written as a complete sentence. It answers the question “who buys

three pounds of baloney?” in the sentence:

Whoever craves tasty fat buys three pounds of baloney.

Who? buys three pounds of baloney: “Whoever craves tasty fat.” Notice

that instead of saying “Whoever craves tasty fat” you could say “John” and

then complete the sentence: “John buys three pounds of baloney.” A noun

clause is merely a fancy noun of more than one word. Any word or group of

words that answers to the question who? or to the question what? is either a

noun or a pronoun.

An adjective clause, on the other hand, answers to the question what

kind of? For instance, if one says “dirty rug,” what kind of? rug: dirty rug.

So in the sentence

The man who loves tasty fat buys three pounds of baloney.

“who loves tasty fat” answers the question what kind of? man: who loves

tasty fat (man). An adjective answers the question “what kind of?” and it

doesn’t matter whether the adjective is merely one word or a whole clause.

Is it answering “what kind of? somebody or something.” If it is, it is an

adjective.

And finally there’s the adverb clause. An adverb can answer how?

when? where? why? under what conditions? and to what degree? In the

sentence

John buys three pounds of baloney because he loves tasty fat.

“because he loves tasty fat” is modifying the verb “buys” in the independent

clause

John buys three pounds of baloney

Why? does he buy?: “because he loves tasty fat.” The clause “because he

loves tasty fat” is an adverb clause since it is modifying a verb and is

answering one of the adverb-questions: why?

What must you clearly remember? You must remember that every

sentence is made up of at least one clause, an independent clause. But a

sentence can contain more than one clause. If it does, at least one of its

clauses has to be independent. But the other clauses in the sentence could

also be independent, as in the sentence

John goes to the store, but Mary stays home.

Here

John goes to the store

but Mary stays home

are both independent clauses. They can each stand alone as a complete

sentence. That means that one can begin a sentence with one of the

coordinating conjunctions (and, but, or, nor, for, so, yet). One can write

John goes to the store. But Mary stays home.

These are both considered to be independent clauses and, in this case, two

separate sentences.

But a clause can also be a dependent clause. A sentence can contain

as many clauses as a writer chooses to fill it with. For instance,

The man who loves baloney goes to whatever store carries the brand that

he likes because not all baloney is the same.

This sentence contains the following subject-verb combinations:

man . . . goes

who loves

store carries

he likes

baloney is

And here are the clauses:

Independent Clause: “The man . . . goes to whatever store carries the brand”

Adjective Clause: “who loves baloney”

Noun Clause: “whatever store carries the brand”

Adjective Clause: “that he likes”

Adverb Clause: “because not all baloney is the same”

Please notice that if an adjective clause is modifying a noun in any

other position than the end-position of another clause, it’s going to break that

clause up.

The sailor who loves baloney is a fool.

“who loves baloney” is breaking up the independent clause “The sailor . . . is

a fool.”

But if the adjective clause is modifying the last noun in a clause, then it

doesn’t break that clause up:

John is a man who loves baloney.

“who loves baloney” is modifying the noun “man,” so the independent

clause remains intact:

John is a man

Here’s the rule: single-word adjectives come before the noun:

That’s a dirty rug (what kind of? rug)--dirty

not

That’s a rug dirty

But an adjective phrase or clause comes after the noun:

The man at the deli is John. (what kind of? man—“the man at the deli)

John is a man who loves baloney. (what kind of? man—“a man who loves

baloney”

You can’t say

The at the deli man is John.

John is a who loves baloney man.

And now the noun clause. The noun clause works as a noun within another

clause. To repeat the whole sentence:

The man who loves baloney goes to whatever store carries the brand that

he likes because not all baloney is the same.

In this sentence there’s an adverb prepositional phrase that modifies the verb

“goes.” “goes where?”: (to whatever store carries the brand). You might

have written “to the deli” instead of “to whatever store carries the brand.”

Then the object of the preposition would be “deli” and not “whatever store

carries the brand.” A noun clause works in any of the six positions that a

single-word noun or pronoun works in:

Subject ...................................... John loves baloney.

Predicate Noun .......................... John is a man.

Direct Object ............................. John kicks the ball.

Indirect Object .......................... John gives his mother a rose.

Object of a Preposition ............. John passes the ball to Raul.

Object of a Verbal ..................... He loves to kick the ball.

Subject................... Whoever is a fool loves baloney.

Predicate Noun ...... John is whatever he wants to be.

Direct Object ......... John kicks whatever ball comes his way.

Indirect Object ...... John gives whomever he meets his best wishes.

Object of Prep. ...... John passes the ball to whoever is there.

Obj. of a Verbal

He loves to kick whatever ball he gets.

And then there’s the adverb clause. It answers to a verb or to another

modifier one of the questions: how? when? where? why? to what degree?

under what conditions? In the sample-sentence

The man who loves baloney goes to whatever store carries the brand that

he likes because not all baloney is the same.

the clause “because not all baloney is the same” tells why? he goes. It is an

adverb clause because (1) it contains a subject and a predicate (baloney is),

(2) it answers the question why? and (3) it is connected to the independent

clause by the subordinating conjunction because. Other subordinating

conjunctions are although, even though, if, since, when, whenever, while,

unless, and so forth. Here’s the list again as copied from The Bedford

Handbook:

after

although

as

as if

because

before

even though

how

if

in order that

rather than

since

so that

than

that

though

unless

until

when

where

whether

while

why

Distinguishing between

Independent Clauses and Noun

Clauses

The noun clause is not an independent clause. An independent clause

can stand by itself as a sentence. For example,

Raul kicks the ball.

or

Raul is a man.

These are both independent clauses. But the following are noun clauses:

whoever kicks the ball

or

whoever is a man

These two clauses cannot be written as sentences by themselves, so

even though they are clauses (because each contains a subject and a

predicate—whoever kicks and whoever is), they are not independent

clauses. They can, however, be used in any position that calls for a noun in

another clause. So, for instance, either of them can work as the subject of a

clause, as a predicate noun, direct object, indirect object, object of a

preposition, or object of a verbal. Let me use “whoever kicks the ball” in

each of these positions:

Subject: Whoever kicks the ball seeks to score a goal.

Predicate Noun: The winner is whoever kicks the ball.

Direct Object: The coach likes whoever kicks the ball.

Indirect Object: He gives whoever kicks the ball a lot of praise.

Object of a Preposition: The team is satisfied with whoever kicks the ball.

Object of a Verbal (in this case of the infinitive): The coach tries to inspire

whoever kicks the ball.

In each of these sentences “whoever kicks the ball” is a noun clause, and

therefore any appropriate single-word noun could work in this situation also:

Subject: Raul seeks to score a goal.

Predicate Noun: The winner is Raul.

Direct Object: The coach likes Raul.

Indirect Object: He gives Raul a lot of praise.

Object of a Preposition: The team is satisfied with Raul.

Object of a Verbal (in this case the infinitive): The coach tries to inspire

Raul.

The point is that a noun clause is a noun. It answers to either the question

who? or what? just as any noun or pronoun does, and it cannot be written as

a sentence by itself. It is not an independent clause.

Summary

I hope that this overview of what constitutes effective writing has

been useful to you. There are other files below this one on this Web page

http://learn.southsuburbancollege.edu/mkulycky/four.htm which will make

you even more aware of some of the finer details of correct writing and

usage. But as I wrote at the very beginning of this explanation, “So one can

ask, ‘What exactly is a person doing when she or he writes effectively?’ My

answer is simple: the person knows how to put a subject in front of a

predicate and to modify that subject and predicate effectively.”

There are only seven parts of speech (since the interjection does not

enter into the expression of a complete thought). The phrases and dependent

clauses are merely clusters of words that can work as nouns, adjectives, or

adverbs. A good sentence is composed of words in their correct positions

and then the phrases and clauses sandwiched in so that they clearly stand for

somebody or something (when the phrases or clauses are nouns) or modify

either nouns/pronouns or verbs/adjectives/adverbs. To know the basics of

grammar is to have the power to say what one wants to say as

unambiguously and un-ambivalently as possible. To write well is also a

very marketable skill. A good writer adds value to any business, agency, or

corporation and therefore has both a better chance to be hired and to be

promoted once she or he is on the job.

Examples of Effective Writing

I’m sure that the reason you want to learn to write effectively is so

that you can earn a better living, but there is also the desire to write

something beautiful, something that gives pleasure in terms of what is under

consideration and how that content is phrased. It’s called aesthetic pleasure.

Great speakers and writers have a knack for getting at things in just the right

way to make the most telling impression.

I have said that “One can ask, ‘What exactly is a person doing when

she or he writes effectively?’ My answer is simple: the person knows how

to put a subject in front of a predicate and to modify that subject and

predicate effectively.” In other words, we’re back to the notion of writing

effective clauses, groups of words that contain a subject and a predicate and

likely also contain adjectives and adverbs in order to make those subjects

and predicates more specific.

I want to look at three examples of excellent writing and show how

the basic concepts from grammar apply to anything that is spoken or written

with the intention of communicating effectively. I have always loved to hear

or read the “Twenty-third Psalm” from the King James version of the Bible.

It is a statement of hope and faith that there is both merit and reward in

being righteous and doing the just thing rather than merely the convenient

thing.

I also admire Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” It insists on

the need for self-sacrifice in the achievement of worthwhile goals. And the

address also expresses what these worthwhile goals indeed are. The

enormous pain of battle is necessary if human beings are to protect and

spread abroad the “inviolable rights” expressed in the Bill of Rights.

And for the third work, I am always inspired by Robert Frost’s “The

Road Not Taken.” It expresses the importance of choosing the road that one

thinks is best for one, accepting the consequences of one’s choice, and

realizing that there is no “going back.” In most cases there are inevitable,

irreversible consequences that attend upon one’s choices and actions.

Permit me to copy each of the three works here below and then look at

the first few lines of each to show how the grammar and punctuation are

everywhere at work when one is creating an effective psalm, or speech, or

poem:

The Twenty Third Psalm

The Lord is my shepherd: I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green Pastures; he leadeth me beside the still

waters.

He restoreth my soul. He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his

name's sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no

evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and staff, they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies; thou

anointest my head with oil: my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I will

dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

from the King James Version of the Bible

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The Gettysburg Address

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

November 19, 1863

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a

new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all

men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any

nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a

great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that

field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that

nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can

not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled

here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The

world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never

forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here

to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly

advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining

before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that

cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here

highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation,

under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the

people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

by Abraham Lincoln

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The Road Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

by Robert Frost

As I mentioned before, I will look at the grammar and punctuation of

the first few lines of each of the three works that I have copied into this file.

But before I do, I want to make a point about grammar and punctuation. It is

in some ways very similar to the html code which creates the pages that one

sees on the Internet. It is there, but it is not visible unless one has been

trained in writing the code. Of course, the “grammar and punctuation” code

is not as removed from what one sees as is the html code behind the visible

page, but it is still true that it is a code which produces given results and that

when the code is not properly written, the message becomes confused and

sometimes not at all understandable. I’ll give an example of the html code

as applied to a page on a Web browser. Below is the opening page of

Google as seen on Microsoft’s Internet Explorer:

And here is what that page looks like if one clicks on “View” in the main

menu at the top of the screen and then clicks “Source”:

It’s hard to believe that the file directly above, typed into a simple wordprocessing program that handles only text, when loaded into a browser

window becomes the page that is the opening page of Google on the Web.

But that’s a fact. And it is also a fact that all effective speaking and writing

is a code that conveys an intended meaning. The words, phrases, and

clauses are spoken or written in a specific order so as to say something both

accurately and clearly. The code has to be written correctly or the intended

page will not show properly.

Before I begin to parse (which means to analyze—determine the parts

of) the first few lines of each entry, let me tell you the order in which I think

it is best to proceed. I think that the first thing to do is to find the clauses.

As you know, a sentence has to contain at least one independent clause. If it

doesn’t, it is a sentence-fragment, an incorrect way to express an idea. For

instance, “Raul kicks the ball” is a perfectly correct clause, since it is a

group of words that contains a subject and a predicate, but “Because Raul

kicks the ball” is also a perfectly correct clause since it also is a group of

words that contains a subject and a predicate. But “Raul kicks the ball” is a

sentence whereas “Because Raul kicks the ball” isn’t a complete sentence.

If someone were to say, “Because Raul kicks the ball . . .” the hearer would

ask, so? “Because Raul kicks the ball” is a sentence-fragment and must be

attached to an independent clause in order to be grammatically correct:

“Because Raul kicks the ball, his team wins.”

Please notice that I am indicating the subject of the clause in red since

it is a noun and the predicate in blue since it is a verb. Also, I’m underlining

the subject with one line and the predicate with two lines.

So let’s find the clauses in the first two sentences of “The Twentythird Psalm”:

[The Lord is my shepherd:] [I shall not want.]

[He maketh me to lie down in green Pastures;] [he leadeth me beside the still

waters.]

I’ve enclosed the clauses in brackets. Remember that any phrase that

occurs in a sentence must be a part of its own clause and not a part of any

other clause. So “to lie down in green Pastures” is an adverb infinitive

phrase that is confined to the clause, “He maketh me to lie down in green

Pastures” and not involved in the clause “he leadeth me beside the still

waters.” And the prepositional phrase “in green Pastures” is also a part of

the first clause because it is an adverb prepositional phrase modifying the

verb of the infinitive, “lie”—lie down where?—“in green Pastures.” Please

also notice that in the second clause, “beside the still waters” is also an

adverb prepositional phrase because it answers the question where? to the

main verb “leadeth”—leadeth where?—“beside the still waters.”

What you should also notice is that all four clauses are independent

clauses. Each one of them could be written as a complete sentence:

The Lord is my shepherd

I shall not want

He maketh me to lie down in green Pastures

he leadeth me beside the still waters

Usually when two independent clauses make up one sentence, they

are connected by a coordinating conjunction (and, but, or, nor, for, yet, so).

But if the second clause explains the first clause or amplifies its meaning in

some important way, one can use a colon [:] to connect the two clauses.

Also, a semicolon [;] can take the place of a coordinating conjunction and

the comma that precedes it. Please notice the semicolon connecting the two

independent clauses of the second sentence:

He maketh me to lie down in green Pastures; he leadeth me beside the still

waters.

But the sentence could also have been written as

He maketh me to lie down in green Pastures, and he leadeth me beside the

still waters.

The comma and the coordinating conjunction and would now be connecting

the two independent clauses.

Therefore, you can see that on the basis of what I have explained

above, the first two sentences of “The Twenty-third Psalm” contain four

independent clauses and three phrases. What’s left to do is to identify each

word as a part of speech:

The (adjective) Lord (noun) is (verb) my (adjective) shepherd (noun): I

(pronoun) shall (verb) not (adverb) want (verb).

He (pronoun) maketh (verb) me (pronoun) to (preposition) lie (verb) down

(adverb) in (preposition) green (adjective) Pastures (noun); he (pronoun)

leadeth (verb) me (pronoun) beside (preposition) the (adjective) still

(adjective) waters (noun).

So there it is: the first two sentences of “The Twenty-third Psalm” have had

their grammatical “code” exposed. Of course one could also talk about the

rhetoric of a sentence, namely, the choices that a writer makes within the

grammatical rules to most effectively convey a meaning. The author of the

first sentence could have written, for instance,

“Because the Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.”

This would be a completely correct sentence, starting with an adverb clause

modifying the predicate “shall not want” of the independent clause—why

shall not want?—“Because the Lord is my shepherd.” But the writer chose

her or his own way of saying what she or he is saying. Both versions are

grammatically correct, but one or the other version sounds better to the