* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chronological overview of the 2009/2010 H1N1 influenza

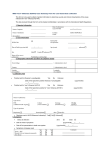

Survey

Document related concepts

2015–16 Zika virus epidemic wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Ebola virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Oseltamivir wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Swine influenza wikipedia , lookup

Antiviral drug wikipedia , lookup

Influenza A virus wikipedia , lookup

Transcript