* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

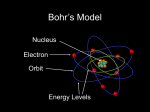

Download Chapter 7 – Quantum Theory and Atomic Structure Chapters 4 and 6

Chemical bond wikipedia , lookup

Photosynthesis wikipedia , lookup

Bremsstrahlung wikipedia , lookup

Relativistic quantum mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Molecular orbital wikipedia , lookup

Particle in a box wikipedia , lookup

Auger electron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

Quantum electrodynamics wikipedia , lookup

Double-slit experiment wikipedia , lookup

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

X-ray fluorescence wikipedia , lookup

Tight binding wikipedia , lookup

Matter wave wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen atom wikipedia , lookup

Atomic orbital wikipedia , lookup

Wave–particle duality wikipedia , lookup

Atomic theory wikipedia , lookup

Electron configuration wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation wikipedia , lookup