* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

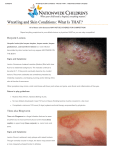

Download NATA Position Statement Skin Diseases

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex research wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Multiple sclerosis research wikipedia , lookup