* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The stress–hypothyroid connection

Hormone replacement therapy (menopause) wikipedia , lookup

Hormone replacement therapy (male-to-female) wikipedia , lookup

Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy wikipedia , lookup

Hyperandrogenism wikipedia , lookup

Growth hormone therapy wikipedia , lookup

Signs and symptoms of Graves' disease wikipedia , lookup

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis wikipedia , lookup

Hypothalamus wikipedia , lookup

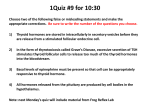

Hypopituitarism wikipedia , lookup

Could stress be affecting your thyroid? Key points in this article Chronic stress leads to overproduction of the hormone cortisol. Cortisol and its precursor (CRH) can inhibit thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Cortisol can also inhibit conversion of the thyroid hormones T4 into T3. Low T3 can lead to hypothyroid symptoms. Simple nutrient and lifestyle modifications can support thyroid function and lower the impact of stress on your overall health and well-being. Yes, we all know stress isn’t good for our health, but we don’t always make the connection between stress and thyroid problems — nor how to change our lives in response. Continuous stress leads to high levels of stress hormones, which can have a negative impact on thyroid function, especially if levels stay high over the long-term. Adrenal and thyroid function originates in the brain Hormones are molecules released by one area of the body to carry messages to another area in the body. The thyroid’s main job is to produce the right amount of thyroid hormone to “tell” your cells how fast to burn energy and produce proteins. The adrenal glands’ primary job is to produce the right amount of stress respond to stress of a zillion kinds. hormones that allow you to The stress–hypothyroid connection Think of the thyroid and adrenals as guardians, or protective intermediaries of the endocrine (hormone-producing) system. They both function as complex sensors, continually responding to ever-changing conditions within the body, and relay information back and forth between the brain and the body. HPT–HPA interactions & feedback loops Because both of these endocrine loops trace back to the pituitary and hypothalamus in the brain, and the hormones produced along these two axes interact, chances of dysregulation are higher along one axis when the other loop is overactive- or underactive. CRH = corticotrophin-releasing hormone; TRH = thyrotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; TSH = thyroidstimulating hormone; T4 = thyroxine; T3 = triiodothyronine. Yet the signaling for release of both sets of hormones originates in an area of the brain known as the hypothalamus, which sends hormonal messages to the tiny gland in the brain called the pituitary. From here, hormonal messages are relayed to both the thyroid and the adrenal glands (along with other destinations beyond the scope of this article). The adrenals and thyroid, in turn, produce hormones and provide feedback to the brain. We call this negative-feedback loop the HPTA (hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid–adrenal) axis. You need just the right amount of cortisol for your thyroid to function optimally. An imbalance can arise all along the HPTA axis and result in either an overactive or underactive thyroid or adrenal glands. As you can see from the diagram, the hormones from each loop interact, and cortisol and thyroid hormone work in concert. So when one of these loops is overactive or underactive, disruption along the other is more likely. This is one reason symptoms of thyroid dysfunction can show up even when your thyroid lab tests appear “within normal limits.” Let’s look at how this happens. How stress can cause thyroid symptoms Much of the medical literature has focused on hyperthyroidism and a condition called Graves’ disease as the main effect of stress on the thyroid. Graves’ is generally caused by an autoimmune response that prompts the thyroid to make too much thyroid hormone. This has been known to occur after a sudden stressful life change. But too much stress can also lead to a slowing of the thyroid, hypothyroidism. Any kind of stress prompts the brain to release CRH (corticotrophin-releasing hormone). This hormone tells the pituitary to send a message to the adrenal glands: make cortisol! But both cortisol and CRH can inhibit thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and the conversion of thyroid hormone T4 to T3. Because every cell in the body uses T3 for healthy function, the decrease in T3 can lead to symptoms like: fatigue cold intolerance weight gain memory loss poor concentration depression infertility hair loss and more This inhibition of your thyroid and hormone receptors often takes place quietly behind the scenes for years without causing overt symptoms. And this is why so many women are caught off-guard when they are diagnosed with a thyroid disorder. They think everything has been going fine and all of the sudden, they feel horrible. The fact is, if you’ve been experiencing chronic stress, stress hormones may have been inhibiting your thyroid function for years. Some patients can even remain in what we call subclinical hypothyroidism, where their lab results are still within the standard normal ranges, but they’re experiencing symptoms. by Marcelle Pick, OB/GYN NP