* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Mission-Related Investing at the F.B. Heron Foundation

Syndicated loan wikipedia , lookup

Modified Dietz method wikipedia , lookup

Financial economics wikipedia , lookup

Beta (finance) wikipedia , lookup

Internal rate of return wikipedia , lookup

Stock selection criterion wikipedia , lookup

Private equity in the 1980s wikipedia , lookup

Private equity in the 2000s wikipedia , lookup

Investor-state dispute settlement wikipedia , lookup

Private equity secondary market wikipedia , lookup

Private equity wikipedia , lookup

Land banking wikipedia , lookup

Corporate venture capital wikipedia , lookup

International investment agreement wikipedia , lookup

Investment banking wikipedia , lookup

Early history of private equity wikipedia , lookup

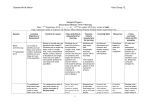

ission-Related Investing A Case Study Expanding Philanthropy: Mission-Related Investing at the F.B. Heron Foundation “The heart of the mission-related investing practice is social impact. We understand that the only true measure of this work is the success of our grantees and investees in producing results.” — Sharon King, President, F.B. Heron Foundation School of Community Economic Development About the F.B. Heron Foundation Based in New York City, the F.B. Heron Foundation is a private philanthropic institution that makes grants to and investments in organizations with a track record of building wealth in low-income communities in the United States. Heron’s mission is helping people and communities to help themselves. Created in 1992, the Foundation supports community-based organizations that can demonstrate tangible results in promoting one or more of the following wealth-creation strategies for low-income families and communities: • Advancing home ownership; • Supporting enterprise development; • Increasing access to capital; and • Reducing barriers to full participation in the economy by providing quality child care. As of December 2006, Heron had $308 million in assets, a $74 million portfolio of mission-related investments and an annual grantmaking budget of $10 million. For more information about the Foundation, visit www.fbheron.org. About the School of Community Economic Development School of Community Economic Development The School of Community Economic Development (SCED) at Southern New Hampshire University is internationally recognized as a leader in community-economic-development education and training, applied research, and the development of innovative communityfinance policy and practice initiatives. SCED’s mission is to advance the creation of just economies and sustainable communities. Founded in 1982, SCED offers a variety of advanced degree and training programs at its main campus in New Hampshire, as well as in collaboration with partners in Los Angeles, Tanzania, southern Africa and the Philippines. SCED has educated more than 2,500 community-development practitioners from more than 100 countries. Graduates build affordable housing, run community-development financial institutions, promote microenterprise programs, and develop commercial projects and small businesses in low-income communities. SCED is also home to the: • Applied Research Center (ARC), which provides support to professionals and policymakers through research, colloquia, institutes and publications; • Center for Community Economic Development and Disability, which leverages resources, infrastructure, techniques and expertise in the service of people living with disabilities; and • Financial Innovations Roundtable, which develops ideas that link conventional and nontraditional lenders, investors and markets to provide increased access to capital and financial services in low-income communities. In 2007, SCED received a New England Higher Education Excellence Award—the Robert J. McKenna Award—presented annually to an outstanding academic program by the New England Board of Higher Education. For more information about SCED, visit www.snhu.edu/ced. Published with generous support by: About AltruShare Securities, LLC Launched in 2005, AltruShare Securities, LLC is a for-profit institutional brokerage firm that is owned by two nonprofit foundations. The first of its kind, the firm allocates two-thirds of its profits in support of community partners with proven experience in community-based philanthropy, investment and research. For more information, visit www.altrushare.com. Table of Contents 3 The Road to Mission-Related Investing at the F.B. Heron Foundation 1996: The Tipping Point Guiding Principles: Progressing Incrementally and Learning by Doing The Results: Better-than-Average Portfolio Performance 4 Heron’s Portfolio In 2006, the F.B. Heron Foundation was recognized as Small Nonprofit of the Year by Foundation and Endowment Money Management magazine, a sister publication of Institutional Investor. The award was based on Heron’s mission-related investment strategy and performance. 5 Lessons Learned Along the Way The First Steps Assembling the Skills: Internal Capacity and Investment Consultants Learning from Foundations and Other Institutional Investors Looking First at Existing Relationships Bridging the Program and Investment Functions Developing a Pipeline of Market-Rate Investment Opportunities 9 Developing a Mission-Related Investment Continuum Below-Market Investments Grants Program-Related Investments (PRIs) Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Insured Deposits (Cash) Fixed Income Publicly Traded Equity Private Equity 13 Managing the Portfolio Asset Allocation Investment Fees Credits This case study was developed by faculty and staff of the School of Community Economic Development, including: • Dr. Michael Swack, founder and dean; • Jack Northrup, adjunct instructor; and • Janet Prince, director of strategic partnerships. Underwriting and Due Diligence Monitoring 14 Mission-Related Investing: Expanding Philanthropy 15 Bibliography and Resource Guide Publications Organizations The Road to Mission-Related Investing at the F.B. Heron Foundation Founded in 1992 with the mission of helping people and communities to help themselves, the F.B. Heron Foundation came into being during one of the greatest economic booms in U.S. history. The strong financial markets of the 1990s not only resulted in the rapid growth of Heron’s asset base but also served to reinforce its focus on asset building and community economic development—as so many Americans did not benefit from the economy’s generation of wealth. 1996: The Tipping Point Faced with the challenges of making effective grants and managing a growing endowment, Heron’s board of directors understood all too well that the scope of the social problems it sought to address required more significant resources than its mandated 5 percent payout. At a regularly scheduled meeting in 1996, Heron’s board reviewed a particular investment manager’s performance for what seemed like hours, leaving little time for program matters. This imbalance caused the board to step back and evaluate the effectiveness of the Foundation. After much discussion, the board put forth the suggestion that because of Heron’s social mission and tax-exempt status, the Foundation should be more than a private investment company that uses its excess cash flow for charitable purposes. Without changes, in the board’s view, there could be very little to distinguish the Foundation from a conventional investment manager. The board began to view the 5 percent payout requirement as the narrowest expression of the Foundation’s philanthropic goals. By looking to the other 95 percent of assets, the “corpus,” the board could “ We recognized that the endowment, left perpetually warehoused, was losing the time value of its potential mission impact. We wanted to behave more responsibly as stewards of philanthropic funds.” — William M. Dietel, Chair, F.B. Heron Foundation conceive a broader philanthropic “toolbox” capable of generating greater social impact than by grantmaking alone. Spurred by this “tipping point,” the board encouraged staff to explore ways in which Heron could engage more of its assets through a combination of grantmaking and “mission-related” investment strategies. The board made a deliberate decision to find ways to leverage an increasing amount of Heron’s resources in pursuit of its mission and therefore maximize the Foundation’s impact in low-income communities. Guiding Principles: Progressing Incrementally and Learning by Doing Developing a mission-related investment strategy did not happen overnight. Heron invested time refining its mission and determining how that mission could be enhanced through a proactive investment strategy. Initially, there was some uncertainty as to how far and how fast the Foundation could move and therefore a reluctance to establish specific mission-related investment targets. By adopting an incremental philosophy, the Foundation was able to test the concept without making any major missteps. Staff was encouraged to explore opportunities in core program areas that would build on existing networks and expertise, as well as to share lessons learned along the way. The Results: Better-than-Average Portfolio Performance Contrary to the perception held by many other foundation trustees and staff that there is a trade-off between financial return and social impact, Heron’s experience during the last 10 years demonstrates that the objective of achieving competitive investment returns can be met—even when incorporating mission-related investments into an overall portfolio and asset allocation. As of December 31, 2006, Heron’s total fund performance was in the second quartile of the Mellon All-Foundation Universe on both a trailing one-year and three-year basis, with 18 percent of assets in market-rate mission-related investments, 6 percent in belowmarket program-related investments (PRIs) and 3 percent in grants. This case study provides highlights of Heron’s experience as the Foundation developed a practice of mission-related investing. While unique in some respects, Heron’s journey offers lessons for any foundation considering whether or how to utilize its resources more fully for mission. 3 GROWTH IN MISSION-RELATED INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO Heron’s Portfolio 80 Market-Rate MissionRelated Investments 70 60 Program-Related Investments 50 MILLIONS As shown in the top graph, Heron’s commitment to mission-related investing has gradually increased with time. As of December 31, 2006, 24 percent of Heron’s assets were invested in missionrelated vehicles spanning the spectrum of asset classes (18 percent in marketrate mission-related investments and 6 percent in PRIs). Compared to the Mellon AllFoundation Universe, Heron’s overall investment performance places it in the second quartile of private foundations in each of the past three years. For more information on Heron’s MissionRelated Investment Continuum and examples of investments across the Continuum, see the section “Developing a Mission-Related Investment Continuum,” which starts on page 9. 40 30 20 10 0 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 OVERALL ASSET DEPLOYMENT, DECEMBER 2006 18% 73% Non-Mission-Related Investment Corpus 6% Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments 3% Program-Related Investments Grants MISSION-RELATED INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO, DECEMBER 2006 Program-Related Investments Cash Deposits or CDs $ 5,800,000 $ 1,500,000 Fixed-Income Securities 21,314,848 — Loans, Senior — 12,004,894 Loans, Subordinated — 2,150,000 Equity, Private 16,000,000 3,300,000 Equity, Public 11,789,209 — Total $ 54,904,057 $ 18,954,894 50 MILLIONS Market-Rate MissionRelated Investments 40 Cash Deposits or CDs 30 Fixed-Income Securities Loans, Senior 20 Loans, Subordinated 10 Equity, Private 0 Equity, Public Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments 4 Program-Related Investments Lessons Learned Along the Way Unsure of the level of risk and opportunity in mission-related investing but convinced that responsible philanthropy involves taking prudent risks for public benefit, in 1997, the F.B. Heron Foundation began a largely uncharted journey to develop a missionrelated investment strategy. A departure from traditional foundation grantmaking and investment management, this journey has changed the way Heron practices philanthropy. Heron’s experience also has challenged the orthodoxy of foundation investing— an orthodoxy that maintains a strict separation between the program and investment functions, and assumes there is a trade-off between competitive financial returns and social impact. Guided by investment discipline, Heron has demonstrated that both program and investment objectives can be achieved when pursued in concert. Adding the investment function to Heron’s philanthropy also has helped the Foundation have a greater stake in the future of low-income people and communities. In short, Heron’s board saw an opportunity to put more of the Foundation’s money where its mission is and has worked diligently to take advantage of that opportunity. Understanding the Distinctions Between Mission-Related and Socially Responsible Investing Mission-related investing—a proactive approach in use across asset classes—is often confused with socially responsible investing, which focuses primarily on social screening and proxy activity in public equities. According to the Social Investment Forum, socially responsible investing “integrates personal values and social concerns with investment decisions [and] considers both the investor’s financial needs and an investment’s impact on society.” As defined by FSG Social Impact Advisors in its report “Compounding Impact: Mission Investing by U.S. Foundations,” mission investments are “financial investments made with the intention of (1) furthering a foundation’s mission and (2) recovering the principal invested or earning financial return.” FSG’s report clarifies this distinction in a discussion of socially responsible screening: “Negative screens, such as avoiding tobacco companies, prevent a foundation from owning stock in companies with operations or products that conflict with its mission. Negative screens do not, however, result in a particular mission investment. Positive screens, such as targeting companies that have strong environmental records, may yield as mission investments if the screening criteria are specifically tied to the foundation’s mission. If not, these screened investments are social investments, not mission investments.” dozens of active investment managers and toward building a mission-related investment portfolio. It’s important to note that investment performance is now as good as when the entire portfolio was under active management but comes at a lower cost. The First Steps Assembling the Skills: Internal Capacity and Investment Consultants As Heron took its first steps toward mission-related investing, the board decided to transfer some of the Foundation’s actively managed investments into index and enhanced index funds. This strategic decision was based on widely accepted research, wholly unrelated to mission investing, that showed no substantial long-term active management premium in many core asset classes. Taking this step not only reduced investment-management fees but also allowed Heron to redirect its resources—away from managing Without extensive in-house investment staffs, most foundations, including Heron, rely on consultants to identify investment opportunities, select active managers and review performance. These advisors play a critical role in helping boards provide financial stewardship. Faced with the issues of constructing a mission-related portfolio and managing transactions, Heron initially turned to its investment consulting firm for guidance. The response was discouraging, as the firm’s consultants lacked knowledge about and interest in mission-related investing. It was at this point that the board realized the extent to which it was challenging conventional thinking and made the decision to build internal management capacity, bringing certain functions in house. The board understood that Foundation systems and work flow might have to change to accommodate some aspects of Heron’s evolving missionrelated investing practice. To address this need, the board encouraged staff to take advantage of various training opportunities. The board also authorized the creation of a new position that would be separate from the finance and administration functions—vice president of investments. In filling the position, the Foundation’s president looked for someone with extensive investment experience and the resourcefulness the Foundation needed to move its mission-related investment portfolio 5 to greater scale. The results of the successful search have been an increase in Heron’s in-house missionrelated investment capacity and level of sophistication, putting the Foundation in a position where it can take advantage of investment opportunities that offer optimal mission, risk and return characteristics. As word of its practice and success spreads, the Foundation’s expertise is often called on by others seeking advice or co-investment opportunities. For mission-related investing to gain wider acceptance, the board and staff knew they needed to find investment consulting firms that would appreciate the Foundation’s commitment to utilizing its resources more fully for mission. In 1999, Heron engaged the services of Evaluation Associates, LLC to provide due diligence on several private-equity transactions. These engagements gave Evaluation Associates the opportunity to learn about the Foundation’s mission-related investing strategy and watch it develop. As the firm’s knowledge of the Foundation grew, Evaluation Associates emerged as an obvious candidate to serve as Heron’s investment consultant for both traditional and mission-related investments, a role Evaluation Associates assumed in 2004. While 10 years ago, it was necessary to build internal capacity to explore mission investing, the marketplace has changed, with evidence of a greater willingness on the part of traditional investment consultants to serve mission-based clients. With foundations driving the conversation with investment advisors, this trend should continue, giving more institutions the guidance and resources needed to develop appropriate mission-related investing strategies. It is only at the insistence of clients that consultants will learn about mission-related investment opportunities and develop the expertise to judge their merit. Learning from Foundations and Other Institutional Investors Early on, Heron looked to other foundations and institutional investors Reality Check: Investment Consulting Firms Share Their Perspectives In an article by Andrew Milner in the September 2006 issue of Alliance magazine, a U.K.-based foundation industry publication, three investment-consulting firms—Cambridge Associates, Mercer Investment Consulting and Jewson Associates—discussed social investing. All three agree that it is not their role to bring up the issue of social investing with their clients, revealing both the challenges and opportunities that foundations face in working with investment consultants on mission-related investing. “Do advisors actively bring social investment options to the attention of foundation investment managers? No…they see it as foundations’ business to seek, rather than to be led.” The article features Cambridge’s view: “We do not intend to proactively raise the issue, other than to let clients know that we are here to help them in this area if they are interested.” Clearly this stance puts the onus on client foundations to initiate the discussion with their consultants and offers the opportunity to drive the discussion of mission-related investing as part of the service foundations expect from their advisors. 6 (including commercial banks, insurers and some public pension funds) for examples of alternative asset deployment. This effort revealed some promising opportunities for missionrelated investing. Heron learned about below-market investments from both the Ford and The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur foundations—the earliest and largest practitioners of PRIs. Heron also learned that The Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation had embarked on an endowment strategy that uses shareholder activism and some direct investing. In its exploration, Heron found willing partners among large commercial banks. Motivated by the federal Community Reinvestment Act, these banks often invested alongside foundations on a below-market basis in nonprofit, community-development financial institutions. The banks, as well as some insurers and public pension funds, also made investments in so-called double-bottom-line real estate and venture-oriented private equity funds seeking to deliver both market-rate financial returns and positive social impact. In expanding its role beyond that of traditional grantmaker, Heron found itself in the company of other types of institutional investors and gained access to potential partners and co-investors. Looking First at Existing Relationships Through partnerships with communitybased organizations and financial intermediaries, Heron has witnessed firsthand the transformative power of investing in America’s low-income communities—primarily through home ownership, enterprise development and access to capital. As such, Heron determined that its grantee pool offered a natural place to look for opportunities to make below-market PRIs. With PRIs in Heron’s philanthropic toolbox, program officers began a fundamentally different dialogue about community-development finance with grantee organizations, especially those capable of utilizing debt. To prompt these discussions, Heron’s staff added a financing section to grant paperwork. Heron views its investments as relationships, not just deals. Because Heron understands the management and operational histories of its grantees, staff has found that the quality of the underwriting is often better than it otherwise might be. This knowledge, trust and understanding have added a valuable dimension to the investment process that has benefited both Heron and its investees. For example, if investments become troubled, having a long-term relationship helps to facilitate conversations in ways that would be difficult for a conventional “lender.” Heron has experienced the benefits of this approach since it first began making PRIs in 1997. Heron has learned that not all grantees need investments and not all investees need grants. Today, while Heron has PRIs with only 14 percent “ Finance officers often stereotype program officers as soft-headed social workers with the easiest job in the world, because how difficult is it to give away money? Similarly, program officers stereotype their finance counterparts as hard-hearted capitalists with little interest in the programmatic work of the foundation, focused solely on the last basis point or two of ‘alpha.’ “ The challenge is getting both sides to work together—by encouraging them and giving them the right incentives—so that everyone is contributing their distinct competencies and maximizing the potential impact of the foundation.” — Luther M. Ragin Jr., Vice President of Investments, F.B. Heron Foundation of its grantees, nearly 75 percent of the Foundation’s PRIs are in groups with which Heron has or has had an established relationship. Now that Heron’s engagement as a mission-related investor is more widely known, the Foundation fields investment requests from familiar and unfamiliar sources. Bridging the Program and Investment Functions Initial discussions with grantees about potential PRIs began with Heron’s program staff—who, in preparing proposals to present to the vice president of investments for first-level approval, reviewed business plans as well as discussed capital needs, Using Resources Effectively Strategic Board Leadership, Staff-Led Implementation It goes without saying that to be successful in developing a mission-related investing strategy, a foundation must have the support of its board. While a foundation’s executive and professional staff may lead the board to a discussion of mission-related investing, a foundation will miss the transformative effects of this shift in strategy without a true and dedicated commitment of its board. With the strategic leadership and full support of its board, staff is responsible for successful implementation. A chief executive officer who encourages openness and flexibility in achieving goals will engender confidence in staff members responsible for implementation. The success of mission-related investing also relies, in large part, on the ability of front-line staff members to think creatively and analytically about where and how they will identify, recommend and underwrite investment opportunities. management capabilities and financial projections. While grantmaking skills could be applied in some areas, it became clear that program staff needed guidance in understanding the investment risks involved and how best to structure deals to mitigate those risks. As Heron’s prospecting efforts turned into a pipeline of tangible deals, the Foundation knew it would benefit from the cross-fertilization of in-house expertise. Heron began a conscious effort to bridge the program and investment functions—a significant departure from how typical foundations are organized and staffed. While many program staff members appreciated the benefits of having access to a new philanthropic tool and the chance to work more closely with investment colleagues, others did not feel as comfortable with the training, mentoring and analysis that making PRIs demanded. The result was some staff turnover through attrition—not uncommon with any significant programmatic change. In replacing staff, Heron looked for—and attracted—officers who felt comfortable with the financial analysis and the investment process. The new staff faced its own challenge of developing expertise in judging the appropriate use of investment “subsidies” to further Heron’s mission. 7 Similar to other aspects of developing its mission-related investing practice, creating a bridge between the program and investment functions took time. The end result is a collaborative model, with staff in the two functional areas working side by side, and investment staff serving as the “tie breaker.” In this model: • • Program staff brings expertise in translating mission into on-theground results. Program knowledge and experience informs strategic thinking about the potential for social impact. Program officers’ familiarity with grantee organizations as well as local and regional networks often serves as an excellent resource in identifying deal flow. Investment staff brings expertise and rigor in underwriting and structuring transactions. This also is critical to weighing risk and return, establishing appropriate performance benchmarks for each asset class, and managing the portfolio within the asset-allocation parameters established by the board. By bridging these functional and cultural divides, Heron benefits from having all of its officers focused on mission. With training from Heron’s in-house investment staff and outside consultants, Heron’s program staff has developed experience in and comfort with prospecting, underwriting and monitoring mission-related investments. Investment staff has gained a concrete understanding of the on-the-ground impact of Heron’s work. In many cases, the staff has seen relationships between the Foundation and investees deepen. 8 “ The board views its fiduciary duty as getting the most social impact possible for each dollar in its endowment. Happily, aggressive mission-related investing policies have not hindered our ability to achieve total investment returns in the second quartile for the past several years.” — William M. Dietel, Chair, F.B. Heron Foundation Developing a Pipeline of Market-Rate Investment Opportunities In addition to working with program staff to make PRIs in organizations where there are existing relationships, Heron’s investment staff works to build the Foundation’s market-rate portfolio of mission-related investments in three primary ways: 1. Conducting active outreach efforts to identify mission-related investment opportunities within various asset classes. To find investment opportunities, Heron relies on a range of outreach activities, from engaging networks to contacting placement agents. As Heron’s Vice President of Investments Luther M. Ragin Jr. says, “If you don’t actively pursue opportunities, then you’re guaranteed not to come across any.” Once an investor starts closing deals, a larger universe of opportunities emerges and the issue becomes identifying the best ones. 2. Creatively adapting traditional investment vehicles and asset managers to mission goals. Heron also has actively solicited opportunities where a bit of creativity has made all the difference. For example, Heron used a simple request-forproposals process to identify fixed-income managers who are capable of managing a separate bond account aligned with the Foundation’s programmatic goals. 3. Researching and developing new investment vehicles, as necessary. While Heron did not have any mission-related investments in public equity for several years, the board knew it wanted to participate in one of the largest and most liquid financial markets in the world. To do so, Heron funded research that led to the creation of the Community Investment Index. Heron is currently beta testing the index using a positively screened, bestin-class methodology to identify publicly traded companies with superior records of engagement with underserved communities. (For more information about the index, see page 12.) In evaluating each potential marketrate mission-related investing opportunity, Heron considers at least three perspectives: • Where does the investment fit within the Foundation’s overall portfolio? • What are the risk and return considerations of the investment? • How does the investment demonstrably further the Foundation’s mission? “We look for expertise in the sectors where we want to invest, and we choose partners based on how well the deal fits our criteria,” says Ragin. Developing a Mission-Related Investment Continuum Below-Market Investments HERON’S MISSION-RELATED INVESTMENT CONTINUUM Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Cash Fixed Income Public Equity Private Equity Grants Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments higher risk lower risk lower risk higher risk Grant Support higher risk Grant Support lower risk Private Equity Subordinated Loans Senior Loans Guarantees lower risk higher risk Cash Below-Market Investments In developing its mission-related portfolio, Heron has explored investment opportunities within all asset classes. To help sort through the opportunities that mission-related investing presents, the Foundation’s staff developed the “Mission-Related Investment Continuum.” The Continuum lays out a set of asset classes available to missionrelated investors. On the left side are below-market investments, including grants and PRIs (private equity, subordinated loans, senior loans and cash). On the right side are mission-related investments that generate market rates of return. The least risky investments can be found in the center of the Continuum; the risk level increases as you move toward both ends. (Guarantees are the exception, as their risk level depends on how they are structured.) In developing the Continuum, Heron staff considered the central tenets of traditional investing discipline: asset allocation, performance benchmarking, and security or manager selection. Heron’s asset-allocation policy—which is paramount to portfolio performance— has not changed to accommodate its mission-related investing practice. Rather, mission-related investing 1 opportunities are considered within the overall asset-allocation framework of a well-diversified portfolio. Heron also has identified appropriate performance benchmarks by asset class to evaluate relative performance, and to compare both risk and return for its mission-related investments versus standard, capital market measures. In choosing its mission-related investments, staff considers a number of variables, including track record, investment strategy and market opportunity. As outlined in the sections that follow, Heron has taken advantage of mission-related investment opportunities across the Continuum. In some ways, Heron’s mission is particularly well suited for such opportunities. Foundations that are active in fields where investment and lending may be more limited may find it challenging to identify the same breadth of opportunities. As such, not all foundations will employ mission-related investing along the entire Continuum; one or two asset classes may be sufficient. In these cases, determining where to start depends on opportunities presented that are most consistent with mission and investment goals. Below-Market Investments As core support, grants act as “working capital” for nonprofit organizations. Heron includes grants on its Continuum—even though they do not provide a financial return— because they arguably represent the riskiest below-market “asset class.” In relation to its investment activities, part of Heron’s grantmaking has enabled the Foundation to establish and develop relationships with organizations that are on the road to “investment readiness.” Program-Related Investments (PRIs) Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments higher risk Private Equity lower risk Sub. Loans Senior Loans lower risk higher risk Cash Below-Market Investments Defined in the U.S. tax code, PRIs1 are made by foundations to nonprofit organizations or commercial ventures for charitable purposes. Whether debt or equity, PRIs typically provide funds for specific purposes, such as land conservation, affordable housing, community facilities and communitydevelopment venture capital. According to the Foundation Center’s most recent data, U.S. foundations invested $237 million through PRIs in 2004. Both recipients and investors can benefit from PRIs. For recipients, PRIs offer access to capital on concessionary terms. In some cases, PRIs also help attract other sources of capital—demonstrating nonprofits’ creditworthiness and fueling future The Internal Revenue Service stipulates that PRIs meet three criteria: the investment’s primary purpose must be to advance the foundation’s charitable objectives; neither the production of income nor the appreciation of property can be a significant purpose; and the funds cannot be used directly or indirectly for lobbying or political purposes. 9 growth. Foundations benefit in that the repayment or return of capital is recycled for other charitable purposes. Eligible to be counted as charitable distributions, PRIs also add flexibility in asset management. As foundations’ interest in below-market investing has grown, informal networking has coalesced in the form of the PRI Makers Network. This nationwide association offers networking, professional development, collaboration and outreach to interested funders, including those not currently making PRIs. Heron made its first missionrelated investment in 1997—a PRI in the form of a senior loan to New Jersey Community Capital to expand and improve child-care facilities. As its PRI portfolio has grown, Heron has found many investment opportunities with different risk and return characteristics: • • • Insured deposits in fledgling, rural credit unions at below-market rates through intermediaries such as the National Federation of Community Development Credit Unions; Senior loans to small business loan funds, such as North Carolina-based Self-Help Ventures Fund that invests in businesses and community facilities in low-income communities; Supporting Community-Development Financial Institutions Since its inception in 1985, The Reinvestment Fund (TRF) has helped to finance 14,440 units of affordable housing, 16,610 charter school slots, 29,470 new or retained jobs, 290 businesses, 5 million square feet of commercial space, and 1 million megawatt hours of clean energy—enough to power more than 100,000 homes for a year. This impressive track record in Philadelphia and the Mid-Atlantic region makes TRF a national leader in the financing of neighborhood revitalization. Heron has provided grant support to TRF since 1994. These grants have helped TRF fund operating costs, loan loss reserves and policy work. In recent years, grants have supported the research and development of a sophisticated Outcomes Database, which integrates organizationwide investment information with the ability to generate maps to assist in underwriting decisions, development planning, impact assessment and general research. Heron grants have also helped TRF develop a proprietary analysis and mapping tool, the Market Value Analysis (MVA), which helps municipalities analyze local real-estate-market conditions and guide investments. TRF’s information systems support the investment strategy for its $380 million in assets. Making up part of that capital base is a $500,000 PRI from Heron. Heron’s funds are targeted to the small-business lending program, which TRF uses to make loans to businesses located in and hiring from low-income communities. In different ways, Heron’s grants and PRIs sustain TRF by helping meet its need for capital—grants to cover expenses and PRIs to fund lending—while also supporting Heron’s program and mission goals. Private-equity venture funds, including New Markets Venture Capital Companies, Rural Business Investment Companies and community-development venture-capital funds. At nearly $20 million, Heron’s PRI portfolio offers a steady return, measured against a benchmark of the long-term inflation rate plus 1 percent, without any losses to date. Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Insured Deposits (Cash) Subordinated loans to provide credit enhancement for affordable housing development, such as the New York City Acquisition Fund, LLC; and Using Grants and PRIs Together 10 • Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Cash higher risk lower risk lower risk higher risk Below-Market Investments Market-rate insured deposits offer an inexpensive, low-risk way—either through direct deposits or through intermediaries—to make missionrelated investments. For example, the Certificate of Deposit Account Registry Service (CDARS)—a service of Promontory Interfinancial Network created so community banks could “pool” their $100,000 FDIC coverage limits to attract larger deposits— allows investors to make deposits in certain institutions, including more than a dozen community-development banks, of up to $30 million with full FDIC insurance coverage. As part of its commitment to its access-to-capital program area, Heron places deposits in a number of the nation’s 60 community-development banks and more than 1,000 “lowincome designated” credit unions. To ensure mission fit, Heron adopted a policy that targeted deposits to institutions that: • Are certified communitydevelopment financial institutions In early 2007, TIAA-CREF announced a $22 million market-rate deposit through the Certificate of Deposit Account Registry Service in ShoreBank, the nation’s oldest and largest communitydevelopment bank with branches in Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland. The bank’s assets approach $2 billion. by the U.S. Department of the Treasury; • • Have a significant portion of their lending activity in asset-building activities in low-income communities, such as small business lending and home mortgage origination; and Have an appetite for market-rate deposits. While these criteria made sense to Heron given its programmatic focus, there are many other criteria (health care, education, immigration) that foundations could use to identify prospects. With a $5.8 million portfolio of insured deposits—nearly 2 percent of its total assets—Heron views marketrate deposits as an important part of its engagement in community-development finance. The return to this cashequivalent portfolio is in line with rates offered in the national CD market and compares favorably to the Merrill Lynch 91-day T-bill rate as a benchmark. Fixed Income Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Fixed Income higher risk lower risk lower risk higher risk Below-Market Investments Heron also targets some of its bond allocation in ways that benefit low- income people and communities. In 2001, Heron established a separately managed bond account, giving it control and flexibility in meeting the Foundation’s mission and portfolio goals. Using input from Heron on mission considerations, the Foundation’s fixed-income manager identifies investment-grade fixedincome securities that are issued by both public and private entities. Mission-related bonds range from down-payment assistance for low-income, first-time homebuyers in Texas to “blight bonds” issued by the city of Philadelphia as part of its Neighborhood Transformation Initiative. Heron’s fixed-income manager, Community Capital Management (formerly CRAFund Advisors), has learned to recognize Heron opportunities in the marketplace. Heron’s staff also has uncovered opportunities for the account in the field. Heron’s fixed-income portfolio now contains a wide range of bonds from across the country. Some of the securities are backed by pools of loans originated by community-based nonprofit organizations and aggregated by the Community Reinvestment Fund. Heron’s mission-related fixed-income portfolio stands at $21 million and has outperformed its benchmark, the Lehman Brothers Aggregate, since inception. Publicly Traded Equity Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Public Equity higher risk lower risk lower risk higher risk Below-Market Investments While there is a long history of socially responsible investing, Heron has not often found alignment between its mission and traditional approaches to socially responsible investing. Since relatively few social screens or Improving Data to Enhance Investment Opportunities Working with the Small Business Administration Small business development aims to facilitate a broad range of entrepreneurial and business endeavors. To find securities backed by loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Section 7(a) Loan Guaranty Program that would fit Heron’s mission-related fixed-income investment strategy, the SBA pools needed to be screened on parameters such as location in low-income communities or areas with high concentrations of minority residents. Community Capital Management worked with SBA originators to determine whether information such as location in low- and moderate-income census tracts and number of employees could be added to loan descriptions so that the pooling agencies could develop customized pools of loans for institutional investors. Excited by the possibility that the universe of investors with an appetite for these types of loans could expand, SBA originators provided the necessary information. This adaptation served the needs of all parties involved. Heron could better meet its mission through more careful targeting of its fixed-income investments, the investment manager gained access to a larger universe of investment opportunities for its client and the loan originators were able to expand their reach and attract new investments. 11 shareholder resolutions are related to the goal of asset building or wealth creation for low-income people and communities, Heron’s board made the decision early on to prioritize direct investment strategies. As a missiondriven institutional investor, however, Heron understands the importance of corporate engagement in helping people in low-income communities help themselves. That’s why, in 2005, Heron embarked on a path of research and development for a positively screened, best-in-class methodology for investing in U.S. public equities. With assistance from Innovest Strategic Value Advisors, a research firm with extensive experience in environmental assessment and quantitative modeling, Heron created a methodology for selecting best-in-class companies in each industry in the S&P 900 based on the quality of their engagement with low- and moderateincome communities in the U.S. Taking into account corporate strategy, work force development, wealth creation and corporate philanthropy, this methodology led to the creation of the Community Investment Index. Based on the promising results of a back test, Heron committed a portion of its U.S. Large-Cap allocation for a beta test of the index’s approach. State Street Global Advisors was selected as the asset manager. In 2006, the first full year of the beta test, the index returned 15.0 percent versus 15.3 percent for the S&P 900 and 13.2 percent for the Domini 400, the most widely used benchmark for large-capitalization socially responsible equity investing. Heron is creating a commingled investment product that the Foundation hopes will be attractive to other institutions committed to investing in low-income communities in the U.S. 12 Private Equity Market-Rate Mission-Related Investments Private Equity higher risk lower risk lower risk higher risk Below-Market Investments “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” published in 1995 by Harvard Business School Professor Michael E. Porter, provided the basis for a fundamental rethinking of investor attitudes toward inner-city communities. In his article, Porter argues that past efforts to revitalize inner cities failed primarily because these efforts lacked a coherent economic strategy. “A sustainable economic base can be created in the inner city,” he stresses, “but only as it has been created elsewhere—through private for-profit initiatives and investment based on economic selfinterest and genuine competitive advantage.” In the years since this article was published, scores of private equity funds—real estate, venture, mezzanine and buyout—have emerged under experienced, professional managers with an explicit focus on inner cities and underserved communities. Assets under management of such funds now exceed $5 billion. One of Heron’s first private-equity investments was UrbanAmerica, LP, a private real estate fund that acquires and develops commercial properties in inner-city communities throughout the country, providing opportunities for corporate, government and retail tenants to locate facilities there. The result has been increased property values, improved consumer choices and services, and permanent employment opportunities for neighborhood residents. UrbanAmerica also directs more than 50 percent of its contracts for management, security and landscaping services to communitybased and minority-owned businesses. Focused on real estate and later-stage venture financing, Heron currently has $16 million in outstanding market-rate private equity commitments, measuring their performance against a benchmark of the Russell 3000 plus 3 percent. The real estate portfolio is generating net returns from the low to the upper teens, and venture funds are producing net returns on realized investments of more than 20 percent. Yucaipa Limited Partnerships— Private Equity Making a Difference Yucaipa Corporate Initiatives Fund, LP is a private equity fund that invests in corporate partnerships that relocate or expand their operations in underserved communities. One of its investments is Picadilly Cafeterias Inc., a chain of family-style restaurants primarily located in the South. In 2004, Yucaipa rescued Picadilly Cafeterias from bankruptcy. Yucaipa then made an equity investment that financed improvements in operations, which led to increased profitability. By preserving 5,200 jobs and creating an additional 600 jobs for local residents, the investment also fueled economic growth and created positive change in many low-income communities. Managing the Portfolio As mentioned earlier, Heron fulfills its fiduciary duty by paying close attention to asset allocation, investment fees, underwriting and due diligence, and monitoring. Asset Allocation As is the case for most institutional investors, Heron’s board establishes an asset-allocation strategy for the Foundation’s portfolio based on total return, as well as liquidity and diversification. Mission-related investment opportunities are considered within this asset-allocation framework. Heron’s current asset allocation is approximately 65 percent in equities, 25 percent in fixed-income securities and 10 percent in alternative investments, such as private equity. This allocation governs all investing, both traditional and mission-related. Investment Fees With nearly one-half of its investment portfolio in index and enhanced index investments, Heron’s investmentmanagement fees were 34 basis points in 2006. This is below the mean of other private foundations in widely known investment surveys. Underwriting and Due Diligence Heron’s program officers are involved in underwriting PRIs as a natural consequence of sourcing deals from the grantee pool. Officers begin by formulating a mission-related investment thesis that makes a case for investing from both a program and a financial point of view. To provide additional rigor to underwriting and mentorship opportunities for program officers, Heron has developed a practice of requiring supplemental third-party “ In order for a foundation to maximize its value, the general understanding of philanthropy must shift from one that is transactive (i.e., a form of wealth re-distribution) to one that is investment-oriented (i.e., focused upon long-term value created through the application of available resources).” — Jed Emerson, Generation Foundation, in “A Capital Idea: Total Foundation Asset Management and the Unified Investment Strategy” due-diligence reviews for all of its below-market mission-related transactions. This “second pair of eyes” provides program officers with a partner during the due-diligence process and provides Heron with an independent, arm’s-length review. Heron’s cadre of third-party consultants is a cost-effective way to maintain a deep bench of expertise. However, these external reviews supplement, not supplant, staff’s judgment. As is the case with grantmaking, program officers are ultimately responsible for making wholehearted and well-reasoned mission-related investment recommendations. Investment staff underwrites Heron’s market-rate, mission-related investments. Due diligence, which often includes a third-party review to complement staff efforts, involves consideration of the manager’s investment thesis, market opportunity, return potential and risk assessment. The Foundation looks to third-party reviewers for help in understanding the investment risks in a given transaction, not to assess social impact. track developments in PRIs. Additionally, the staff meets on a quarterly basis to review the risk level in each transaction. As in its underwriting, Heron uses third-party monitoring reports for all of its mission-related investments. This third-party approach has allowed Heron to create a larger universe of analysts, selected according to their expertise in specific asset classes. This approach also has increased Heron’s ability to cover a range of deal structures and transaction types. Monitoring efforts have revealed a number of issues that investees face, such as leadership transitions, fundraising disappointments and market changes that sometimes lead to deteriorating financial health. In most cases, Heron has taken steps to stay with its investees through tough times, such as by requiring more frequent monitoring, collateral or principal amortization. Monitoring Because investments take on a life of their own and rarely remain static with time, Heron monitors all aspects of its portfolio. Program officers, in consultation with investment staff, 13 Mission-Related Investing: Expanding Philanthropy During the past 10 years, Heron’s experience shows that the objective of achieving competitive investment returns can be met while incorporating missionrelated investments into a diversified portfolio. Guided by investment discipline and incremental implementation, Heron has demonstrated that both program and investment objectives can be achieved when pursued in alignment with a foundation’s mission. As Ragin points out, “Back in 1997, if you were to ask the board, ‘In how many asset classes are we likely to find appropriate investments that align with our mission?,’ they probably would have said, ‘There aren’t many, but let’s try to find the best opportunities we can and do what we can.’” Today, the answer is clearer: In the field of community development, there is a variety of strong investment opportunities across asset classes and return hurdles that not only aligns with Heron’s mission but also can increase the impact and reach of its work. Investment performance ranking is not subjective. By the nature of quartiles, one-half of ranked foundations enjoy higher investment returns than the other half. With 24 percent of its assets in missionrelated investments—including 6 percent at below-market rates of return—Heron’s ability to generate above-average investment performance and grow the level of the endowment presents an opportunity for the entire sector. Today’s mission-related investing environment is very different from the one Heron encountered in 1996. Now, there are mission-related investment vehicles in virtually every asset class. As Ragin says: “That is really the story here. While each foundation will 14 “ Learn by doing. If we hadn’t just moved ahead and done our first program-related investment in 1997, we’d still be sitting around talking about doing it. This capacity was not developed overnight, but it did happen over time.” — Mary Jo Mullan, Vice President of Programs, F.B. Heron Foundation have to work at visualizing its own mission through an investment strategy, there is no need to reinvent the wheel.” Financial intermediaries and consultants provide both investment products and advisory services. Perceived and actual levels of risk have declined with time. With the successful return of capital and interest, the nonprofit sector has demonstrated its ability to build investment capacity and offers a broad range of opportunities for value-seeking investors. As a medium-sized, national foundation, Heron seeks to deploy its resources as effectively as possible. Making mission-related investments, in addition to grants, has increased the level of engagement and intensified the need to focus on impact as the criterion for resource allocation. Heron’s staff and board now spend their time actively managing and reviewing mission-related investing and grantmaking activities as part of an overall portfolio approach—a shift away from the frustration experienced when the board spent inordinate time on investment manager performance. Board meetings now focus both on portfolio performance and mission impact. Mission-related investing is the intersection of the two—allowing for more far-reaching discussions among Heron’s leadership. The F.B. Heron Foundation has moved well beyond the tipping point toward a fully diversified missionrelated investing practice. Indeed, Heron continues today to expand its vision and investment horizons—using its broad experience in working with community-based organizations—to bring the full weight of its resources, and those of other investors, to bear on its mission. No longer does Heron view low-income people and neighborhoods merely as candidates for grant funding. It views them as good investments. This case study seeks to contribute to the dialogue on the expanded use of foundation assets. Just as the F.B. Heron Foundation believes that mission-related investing has enriched its philanthropic practice, other foundations may find that if they were to harness more of their resources for the issues that concern them, philanthropy and society would stand to gain. Bibliography and Resource Guide Clark, Catherine H. and Gaillard, Josie Taylor, “The Double Bottom Line Private Equity Landscape in 2002–2003,” Rise Capital Market Report, July 2003. Lingenfelter, Paul E., “Program Related Investments: Do They Cost, Or Do They Pay?,” The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, 1996. Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) Data Project, “Providing Capital, Building Communities, Creating Impact,” 4th Edition, 2006. Milken Institute, “What Are Emerging Domestic Markets?” from the sixth annual Milken Institute Global Conference, Los Angeles, Calif., April 2, 2003. “A New Journey: Aligning Investment with Mission at the Northwest Area Foundation,” Northwest Area Foundation. Cooch, Sarah and Kramer, Mark, “Compounding Impact: Mission Investing by U.S. Foundations,” FSG Social Impact Advisors, March 2007. Nonprofit Finance Fund, “Capital Structure Counts,” New York, N.Y., 2002. www.nwaf.org www.fsg-impact.org Angelides, Philip, “The Double Bottom Line: Investing in California’s Emerging Markets,” May 2000. Cooch, Sarah and Kramer, Mark, “Investing for Impact, Managing and Measuring Proactive Social Investments,” Foundation Strategy Group, for the Shell Foundation, January 2006. The following publications and Web sites offer information about missionrelated investing. Many also served as sources for this case study. Publications “2005 Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the United States, 10-Year Review,” Social Investment Forum, January 2006. www.socialinvest.org Baxter, Christie I., “Program-Related Investments: A Technical Manual for Foundations,” 1997. Berenbach, Shari, and Khor, Jacqueline, “Private Investment for Social Goals and the Blended Value Capital Market” (discussion draft based on “The Investors Toolkit,” by Jed Emerson, Timothy Freundlich and Shari Berenbach), September 2004. Brody, Francie, “Great Ideas: Social Investments Supporting Human Services,” Brody, Weiser and Burns, November 2002. Brody, Francie; McQueen, Kevin; Velasquez, Christa; and Weiser, John; “Current Practices in Program-Related Investing,” 2002. Brody, Francie; Weiser, John; and Miller, Scott; Joffe, Phyllis (editor), “Matching Program Strategy and PRI Cost.” Cambridge Associates, “Social Investing,” 2007. Cambridge Associates, “Social Investing: A Statistical Summary,” 2007. Emerson, Jed. “A Capital Idea: Total Foundation Asset Management and the Unified Investment Strategy,” Generation Foundation, April 1, 2004. Emerson, Jed, “Where Money Meets Mission: Breaking Down the Firewall Between Foundation Investments and Programming,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, summer 2003. Funders’ Network for Smart Growth and Livable Communities, “Doing Well by Doing Good: Innovative Foundation Investments in PlaceBased Smart Growth Development,” September 2002. Korman, Rochelle Esq., “Legal Issues of Leverage Through Program-Related Investments,” from Merrill Lynch Private Wealth Management Third Annual Conference for Foundations and Strategic Philanthropy, Princeton, N.J., June 6, 2003. Olsen, Sara and Tasch, Woody (editor), “Mission Related Investing, A Workshop for Foundations with Detailed Examples from the Field of Community Investing,” October/ November 2003. www.investorscircle.net Porteous, David and Narain, Saurabh, “Defining and Measuring the Performance of Community Development Banking Institutions,” NCIF Development Banking Conference, Chicago, Ill., November 2006. Porter, Michael E., “The Competitive Advantage of the Inner City,” 1995. Porter, Michael E. and Kramer, Mark R., “Philanthropy’s New Agenda: Creating Value,” Harvard Business Review, November–December 1999, reprint. Ragin, Luther M. Jr., “New Frontiers in Mission-Related Investing,” New York, N.Y., The F.B. Heron Foundation, 2004. Thomsen, Mark, and Wheat, Doug, “The New Fiduciary Duty,” Business Ethics, spring 2003. 15 Viederman, Stephen, “New Directions in Fiduciary Responsibility,” Stephen Viederman, 2003. “Foundations and Mission-Related Investing,” August 2002. www.foundationpartnership.org Yago, Glenn; Zeidman, Betsy; and Schmidt, Bill; “Creating Capital, Jobs and Wealth in Emerging Domestic Markets,” Milken Institute, Santa Monica, Calif., 2002. Organizations F.B. Heron Foundation www.fbheron.org CDFI Fund www.cdfifund.gov National Federation of Community Development Credit Unions State Street Global Advisors www.natfed.org The Reinvestment Fund (TRF) Neighborhood Transformation Initiative www.trfund.com www.phila.gov/nti UrbanAmerica, LP New Jersey Community Capital www.urbanamerica.com www.newjerseycommunitycapital.org Yucaipa Corporate Initiatives Fund, LP 9130 W. Sunset Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90069 New Markets Venture Capital Program http://www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ pages/jan2004tlc.html New York City Acquisition Fund, LLC www.nyc.gov/html/hpd/html/developers/ acquisition_fund.shtml PRI Makers Network www.primakers.net www.ccmfixedincome.com Promontory Interfinancial Network (home of the Certificate of Deposit Account Registry Service or “CDARS”) Community Reinvestment Fund www.cdars.com www.crfusa.com Rural Business Investment Program Evaluation Associates, LLC http://www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ pages/jan2004tlc.html Community Capital Management (formerly CRAFund Advisors) www.eval-assoc.com Ford Foundation www.fordfound.org Foundation Center http://foundationcenter.org FSG Social Impact Advisors (formerly Foundation Strategy Group) School of Community Economic Development www.snhu.edu/ced Self-Help Ventures Fund www.self-help.org ShoreBank www.fsg-impact.org www.shorebankcorp.com Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Small Business Administration www.innovestgroup.com www.sba.gov Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation Social Investment Forum www.noyes.org www.socialinvest.org John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Southern New Hampshire University www.macfound.org 16 www.snhu.edu www.ssga.com School of Community Economic Development © School of Community Economic Development, 2007