* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download webquest sparta athens handout

Liturgy (ancient Greece) wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Acropolis of Athens wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Sacred Band of Thebes wikipedia , lookup

Prostitution in ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

First Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup

Theban–Spartan War wikipedia , lookup

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

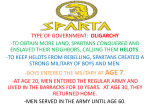

Spartan Women Spartan women enjoyed considerably more rights and equality to men than elsewhere in the classical world. Women from Spartiate families were raised to embrace the same ideals of service to the state as Spartan men were. They did not serve in the army, although they took a lively interest in it and its achievements. Spartan women had limited rights. They could own land and inherit property but they could not vote or hold public office. Their aspirations were to be physically strong companions for their military husbands and to breed strong, healthy boys and raise them to be brave soldiers and heroes. Spartan women were unusual in the amount of freedom they were allowed. They trained exclusively in athletics and gymnastics. Unlike elsewhere in Greece, spinning and weaving were regarded as activities only fit for slaves. Perfumes, jewellery and cosmetics were forbidden, as were fine clothes and elaborate hairstyles. Spartan women exercised and danced naked. Their physical exercise gave them a reputation throughout Greece for graceful, natural beauty. A bronze statue of a Spartan woman (sixth century BC) Spartan Men Since Spartan men were full-time soldiers, they were not available to carry out manual labour, instead, Helots (Spartan slaves) were forced to complete all laborious activities, such as farming. Spartan citizens were refused by law from trade or manufacture, which consequently rested in the hands of the Perioeci. The Perioeci were the businesspeople and artisans of ancient Sparta. The Perioeci monopoly on trade and manufacturing in one of the richest territories of Greece explains in large part the loyalty of the perioikoi to the Spartan state. Spartiates, on the other hand, were forbidden (in theory) from engaging in menial labour or trade, although there is evidence of Spartan sculptors, and Spartans were certainly poets, magistrates, ambassadors, and governors as well as soldiers. The Spartan men participated in matters relating to the Spartan government. Spartan Girls Spartan girls lived at home, not in army barracks. Like boys they were organised into groups and at times they exercised with them. They participated in most sports, including running, wrestling, throwing the javelin and discus, and ball games. Boys and girls competed in choral and dancing competitions. Spartan Boys A Spartan boy’s education was directed towards making him a good soldier. At the age of seven, boys left home and went to live in army barracks. When male Spartans began military training at age seven, they would enter the Agoge system. The Agoge was designed to encourage discipline and physical toughness and to emphasise the importance of the Spartan state. Plutarch wrote that the education of Spartan boys was directed towards three outcomes: 1. To develop the ability to endure hardship and pain 2. To encourage prompt obedience to authority 3. To foster courage and ensure victory in battle Ritual flogging of Spartan boys was part of their culture. It was a test of endurance and part of an initiation ceremony into manhood. Spartan boys were flogged if they were caught stealing, not because it was morally wrong, but because they got caught. The Spartan ethic was so strong that one boy who was suspected of stealing a fox kept it inside his cloak rather than admit to stealing it. Legend says he died having his insides torn out by the fox. Athenian Men Men of Athens were often involved in many civic duties and spent a great deal of their time away from home. When not involved in politics, the men spent time in the fields, overseeing or working the crops, sailing, hunting, in manufacturing or in trade. When they were at home, they were treated with great respect. For fun, in addition to drinking parties, the men enjoyed wrestling, horseback riding, and the famous Olympic Games. When the men entertained their male friends, at the popular drinking parties, their wives and daughters were not allowed to attend. Men of Athens were prepared for peace and war; every man ages 20 to 50 or more could be “called up” for military service”. Athenian Girls Girls stayed at home until they were married. Like their mother, they could attend certain festivals, funerals, and visit neighbours for brief periods of time. Their job was to help their mother, and to help in the fields, if necessary. Girls were trained to be efficient housewives, a position held in the greatest esteem in Athens. Athenian Boys Boys were taught at home by their mothers until they were 6 or 7 years old. In Athens, the education was left up to the father. Private school masters taught the boys of Athens. A trusted slave took the Athenian boys from wealthy families to school. The students learned to write on wax-covered tablets with a stylus. Books were very expensive, so they were rare. At school, the boys in Athens learned mathematics, how to play musical instruments (the lyre) and studied the words of Homer (an ancient Greek epic poet). Boys were trained in sports and the wealthy boys learned to ride horseback. Other sports included wrestling, using a bow and a sling and swimming. At age 14 boys attended a higher school for four more years. At age 18 boys went to military school. They graduated at age 20. Athenian Women Women in most city-states of ancient Greece had very few rights. This includes the women of Athens. They were under the control and protection of their father, husband, or a male relative for their entire lives. Athenian women were not citizens and so were not permitted to take a direct and active role in Athenian political life. Some women, no doubt, could influence their husbands or male companions but, generally speaking, Athenian women had no political or legal rights. By law they were considered to be the property of their fathers and then of their husbands. Generally speaking, an Athenian woman’s world was in the home. The most important duty of Athenian women was to make life comfortable for men. Inside the home an Athenian woman cooked, spun, wove cloth, reared children, managed the family budget, supervised servants and made clothes. Athenian women had little formal education and only a few women could read. If Athenian women had their husband's permission, they could attend weddings, funerals, some religious festivals, and visit female neighbours for brief periods of time. But without their husband's permission, they could do none of these things. They could not leave the house, not even go to a temple to honour their gods, without their husband's permission. Marriage was very important to Athenian women. Usually their families chose their husbands. Often the bridegroom and bride did not see each other until after the wedding. At the engagement ceremony a contract was made between the bride’s father and the bridegroom and a dowry, usually a gift of money, was agreed upon. Most girls were married at around 12 to 15 years of age to older husbands of around 30 years of age. Democracy in Athens Athens was a city-state in which citizens had the most involvement in the government. The Athenians called their system of government democracy from the two Greek words demos, meaning people and kratia meaning rule. It is important to realise that involvement in political life was restricted to citizens; that is, to adult males born in Athens of free parents. Women, foreign born inhabitants (metics) and slaves were excluded. This meant that, in a population of about 150,000 people, only about 30,000 could be considered citizens. Athenian took turns in running the government. A committee organised meetings of the Assembly, or Ecclesia. Each year the members were chosen by drawing lots. This gave each citizen the change to assist for a short time, but prevented anyone from becoming too powerful in the government. Ostracism was another method use to prevent ambitious men from seizing power. Ostracism meant that any politician could be sent into exile for 10 years by a vote in the Assembly if he became a threatening influence. Committees of citizens chose men to administer or run certain aspects of the government for short periods of time. They organised matters such as building new city walls or arranging food and weapons for the army. The Assembly met every nine days. At these meetings, citizens could speak in debates and vote on whether to pass a decision. A council of 500 dealt with the day-to-day business of the city-state. These men were elected each year by the Assembly. Fifty members came from each of the 10 tribes into which the Athenian citizens were divided. Meetings were held in the Bouleuterion in the Agora. The Assembly also chose 10 war leaders, or generals to run the army and navy. (In Greek, the world ‘general’ means admiral.) Generals were allowed to serve for several years to avoid the disasters that could be created by changing generals too often in the middle of a war. Pericles served as a war general for 26 years. His oratory, or public speaking skills, helped him to persuade the Assembly to elect him as general 14 times. The People’s Courts Jury courts were formed from the citizens. Citizens drew lots to decide who would be juror. There were no judges and no professional lawyers. The accused was delivered a summons (an order to appear at court) to give his own defence. His defence speech might have been prepared by a professional speech writer. The development of Athenian democracy was a long and gradual process, basically beginning with the agrarian reforms of Solon. It reached its peak during the time of Pericles and the Golden age of Greece. During Pericles’ term of office, Athens had the following features of democratic government: Three leader, archons, with mainly ceremonial function, were elected annually A constitution which set down the rules of government All male citizens could propose, debate and vote on legislation All male citizens could propose, debate and vote on legislation All male citizens could stand of office All male citizens could vote for generals or chief magistrates Public office was held for one year only All public officials were carefully supervised The people’s courts had total jurisdiction Jurors and official were paid Governing Sparta Spartan government was a unique combination of monarchy, oligarchy and democracy. It consisted of: Two kinds The Ephorate (board of give chief public officials or administrators) The Council of Elders Assembly of Spartiates (or Assembly of Citizens). Sparta was the only Greek city-state to have an Ephorate and to be ruled by kings for most of its history. The Spartans were admired by other Greeks for the clear structure of their constitution. After a struggle between the kings and the people, the kings gave up their civil jurisdiction. By the end of the seventh century BC, the Ephorate had won greate political power. Any Spartiate could become an ephor. Ephors could: Administer civil justice, including arresting and fining a king Issue orders to mobilise armies Control army generals Command the secret police Preside over the Council and Assembly Ephors were elected for only one year. When they became private citizens again, they could be called to account for any of their actions as ephors. The Council of Elders also limited the kings’ power. The kings, however, were members of the Council of Elders. The kings, however, were members of the Council of Elders. The other 28 members had to be over 60 years of age. Their positions were chosen by clapping by the Assembly of Spartiates. Positions in the Council of Elders were a reward for merit, for councillors had to be honourable and capable men. Their function was to: Offer advice on political decisions Prepare and deliberate on bills to be presented to the Assembly of Spartiates for voting Act as a court of justice for cases of treason The Spartiate Assembly had the appearance of democracy only for those who were Spartiates. The Assembly met every month, but members were not allowed to debate. They generally shouted ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the Council of Elders’ proposals. There was no counting of votes – only the mood of the citizens on issues was apparent. The real political power lay in the hands of the Council of Elders because they determined the issues presented to the Assembly. Sparta: A Military State The Spartans were the descendants of the Dorians – the groups of fierce warriors who had invaded the Greek mainland c. 1200-1000 BC. The group of Dorians who became known as the Spartans settles in the rich Eurotas River Valleu in Laconia. Originally they lived in five villages which united to form the city of Sparta. Sparted annexed its surrounding villages and eventually the whole of Laconia. Around 740-30 BC, the Spartans, in the search for more land to feed their increasing population, conquered the neighbouring state of Messenia. They treated these conquered peoples as helots or slaves. Once the Spartans took over messenia they face a huge problem. The indigenous tribes in Lacedaemonia outnumbered the Spartans. The Spartans had three choices: 1. To exterminate the indigenous tribes 2. To intermarry with the indigenous population 3. To create institutions which would allow them to assert their authority over the conquered tribes The Spartans decided to adopt the third option. The non-Dorian, indigenous people were forced to become slaves, or helots. The other Dorian tribes who had settled in the area were given the status of perioeci, or ‘fringe dwellers’. Their outlook on life changed about 650 BC, when the helots of Messenia revolted. This revolt deeply disturbed the Spartans who feared for their survival. The rebellion was eventually crushed, but the Spartans were determined not to allowed it to happen again. They restructure their social and political organisation. Sparta developed in a military camp. Its aim was to produce brave and tough soldiers who could devote their whole lives to safeguarding the Spartan state, which was under constant threat from the helots. Sparta developed a reputation of having the finest army in Greece. Spartans were admired for their courage, tought discipline and obedience to the state. The strength of Sparta's hoplite forces let the city become the dominant state in Greece. By the end of the fifth century BC, the Spartans had developed a reputation of austerity (sterness) and stoicism (the endurance of pain or hardship without a display of feelings and without complaint). This development was gradual. In early Sparta, Spartans were not much different in outlook and social organisation from other Greek-speaking people at the time. They were nethusiastic about poetry and art, enjoyed dancing at religious festivals and produced a distinctive style of pottery. Spartiates To be a full Spartan citizen, or a Spartiate, residents in Laconia had to prove their Spartiate ancestry, be male, be 30 years old, submit to Spartan education and discipline and be a member of a military mess. A Spartiate’s duties were to: Defend the state against the helots Defend the city-state of Sparta A Spartiate’s life belonged to the state. He lived in a military club, not at home with his family. A Code of Honour Spartiates lived by a high code of honour – courage, loyalty, endurance and obedience to the state. A Spartiate could lose his citizenship if he breached this code of honour – especially if he were guilty of cowardice. The Athenians and the Golden Age of Greece Unlike Sparta, Athens did not have an established army. All athenian male adults were expected to be prepared to go to war at any time. The type of contribution an Athenian citizen made to a war depended on his means. Athenian soldiers, like their Spartan counterpart, were hopelites. Thei helmets were decorated with horse hair, their breastplates had strips of linen reinforced with metal discs and their shields were made of a wood covered with bronze. They carried swords and spears. The Rise of Athens The ancient city-state of athens was possibly the most important of the Greek city-states. By the fifth century BC Athens had emerges as the centre of power in the area known as Attica. The Athenians developed a rich and powerful way of life which influenced the whole of Western civilisation. A Greek city-state usually consisted of: An acropolis An agora (marketplace) and people’s homes, below the acorpoli The countryside around the city The Acropolis, in Athens, is a steep, rocky hill about 150 metres high and 1.6 kilmetres from the sea (and the port of Piraeus). This natual fortress helped to protect Athens from pirates and invaders. By the sixth century BC th Acropolis, with its many beautiful temples, had become the religious centre of Athens. The Parthenon was the most important building on the Acropolis. It was dedicated to the goddess Athena. Other buildings included the Erechtheum (which housed the statues of Poseidon, Athena and the king Erechtheus) and the Sanctuary of Zeus. The city of Athens remained small even though the number of people in the city-state was greater than in most other Greek city-states. Most people lived in the countryside – either on the coast, in the hills or on the plains – and worked as farmers. Farming was the basis of Athenian wealth. However, the climate in Attica was dry and the mountainous landform did not allowe the Athenians to grow enough food for everyone. In particularly, grain had to be importated. Trade became an essential element in sustaining the Athenians and a significant factor in contributing towards the Athenians’ material wealth. Before the Perisan Wars, strong leaders, such as Solon, Peisistratus and Cleisthenes, transformed Athens from a small agrarian state into a thriving commercial and industrial city. The Agora The Agora was an open, tree-lined square in the centre of the city of Athens, below the Acropolis. The word agora mean ‘gathering place’. The Agora was the focus of Athenian political, social and commerical life. It was only a day’s walk from the most distant village in Athens. All the buildings needed to run the Athenian democracy were located in the Agora. These included: The Bouleuterion, where the Council of 500 met The Strategeion, or military headquarters The Tholos, or administrative centre The law courts The mint Produce from the surrounding farms was sold in the Agora’s stoas, or open-side markets. Olives, graped and figs were the most important crops in ancient Athens. Today, olives are still an important export industry. In ancient Athens, slaves harvested olives on the wealthier estates. On the poorer farms the harvest was a family affair. Women and children knocked the olives to the ground with long sticked while the older boys climbed to reach the fruits from the high branches. The olives were hten packed into baskets and crushed in a nearby olive press. To do this, the arm of the press was weighted with stones and swung on. The crushed oil rain into a big bottling jar and the baskets stopped the pits and skin from going into the jar and spoling the oil. Wine presses were also very simple. Wokers trod on the grapes in their bare feets to squeeze out the juice. The Acropolis in Athens. The Parthenon is the most prominent building on the Acropolis.