* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

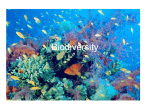

Download Queensland`s biodiversity under climate change:

Politics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change denial wikipedia , lookup

Climate sensitivity wikipedia , lookup

Climate change feedback wikipedia , lookup

Economics of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate engineering wikipedia , lookup

Climate resilience wikipedia , lookup

Citizens' Climate Lobby wikipedia , lookup

Climate governance wikipedia , lookup

Hotspot Ecosystem Research and Man's Impact On European Seas wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on human health wikipedia , lookup

Attribution of recent climate change wikipedia , lookup

Solar radiation management wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Tuvalu wikipedia , lookup

Media coverage of global warming wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in Australia wikipedia , lookup

Climate change adaptation wikipedia , lookup

Climate change in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Scientific opinion on climate change wikipedia , lookup

Public opinion on global warming wikipedia , lookup

IPCC Fourth Assessment Report wikipedia , lookup

Climate change and poverty wikipedia , lookup

Effects of global warming on humans wikipedia , lookup

Surveys of scientists' views on climate change wikipedia , lookup