* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Lecture Notes - Fullfrontalanatomy.com

Survey

Document related concepts

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Artificial heart valve wikipedia , lookup

Congenital heart defect wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

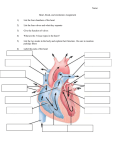

Chapter 18 I. The Heart Location and Orientation Within the Thorax (p. 500, Figs. 18.1–18.2). A. The heart is a double pump; the right side pumps blood to the lungs for oxygenation, i.e., the pulmonary circuit; the left side pumps blood throughout the body to nourish tissues, i.e., the systemic circuit (p. 500, Fig. 18.1). B. The four chambers are the right and left atria (receiving chambers) and the right and left ventricles (pumping chambers) (p. 500, Fig. 18.1). C. The cone-shaped heart lies obliquely in the mediastinum; the size of a fist, approximately 250–300 grams, its apex points toward the left hip and the broad posterior base is directed toward the left shoulder (p. 500, Fig. 18.2). II. Structure of the Heart (pp. 500–503, Figs. 18.3–18.5). A. The heart is enclosed by the pericardium; pericardium consists of a superficial layer (the fibrous pericardium and parietal layer of serous pericardium), and a deeper visceral layer of the serous pericardium that covers the heart surface (p. 502, Fig. 18.3). B. The wall of the heart has three layers: a superficial epicardium (same as the visceral layer of serous pericardium), a middle myocardium (the cardiac muscle), and a deep endocardium (heart lining) (p. 502, Fig. 18.3–18.4). C. The heart has four chambers (pp. 502–503, Fig. 18.5). 1. Right and left atria are located superiorly and separated by an interatrial septum. 2. Right and left ventricles are located inferiorly and separated by an interventricular septum. III. Pathway of Blood Through the Heart (pp. 503–508, Figs. 18.6–18.7). A. The pathway of blood through the heart begins with a drop of oxygen-poor systemic blood arriving at the right atrium and terminates with an oxygen-rich drop of blood leaving the left ventricle (p. 503 and 507–508, Fig. 18.6). B. A sequence of atrial contractions and ventricular contractions (called a heartbeat) propels blood through the heart (p. 507). C. The muscular walls of the right and left ventricles reflect differential pressures in the pulmonary and systemic circuits (pp. 507–508, Fig. 18.7). IV. Heart Valves (pp. 508–511, Figs. 18.8–18.11). A. The four heart valves are the two atrioventricular valves and the two semilunar valves (p. 508, Fig. 18.8). 1. The right AV valve is the tricuspid and the left AV valve is called the bicuspid or mitral. 2. The two semilunar valves are the pulmonary semilunar valve and the aortic semilunar valve. B. A valve consists of two or three flaps of endocardium called cusps; the AV valves lie at the junctions between the atria and ventricles; the semilunar valves lie at the junctions between the ventricles and great arteries (p. 508, Fig. 18.8). C. Heart valves open to allow blood to flow and close to prevent backflow in response to differences in blood pressure on each side of the valves (p. 508, Fig. 18.9–18.10). D. Heart sounds (the familiar “lub-dup”) are produced by the closing of the valves (pp. 509–511, Fig. 18.11). V. Fibrous Skeleton (p. 511, Fig. 18.8a). A. The fibrous skeleton of the heart surrounds the heart valves and functions in several ways, one of which is to anchor the valve cusps (p. 511, Fig. 18.8a). VI. Conducting System and Innervation (pp. 511–512, Figs. 18.12–18.13). A. Heart muscle generates and conducts electrical impulses; the intrinsic production of impulses can be altered by extrinsic neural controls (p. 511). B. The conducting system of the heart is a series of specialized cardiac muscle cells that carries impulses throughout the heart; among the several components are the SA node and AV node (pp. 511–512, Fig. 18.12). C. Innervation to the heart is served by visceral sensory fibers, parasympathetic fibers, and sympathetic fibers; parasympathetic fibers slow the heart rate and sympathetic fibers increase the heart rate (p. 512, Fig. 18.13). VII. Blood Supply to the Heart (pp. 512–514, Fig. 18.14). A. Coronary arteries supply oxygenated blood to the heart muscle; cardiac veins drain the deoxygenated blood from the heart (pp. 512–514, Fig. 18.14). VIII. Disorders of the Heart (pp. 514–516). A. Coronary artery disease is caused by atherosclerotic blockage of the coronary arteries (p. 514). B. Heart failure is a progressive weakening of the heart as it fails to keep pace with the demands of pumping blood and thus cannot meet the body’s need for oxygenated blood (p. 516). C. Disorders of the conduction system include atrial and ventricular fibrillation (p. 516). IX. The Heart Throughout Life (pp. 516–519, Fig. 18.15–18.17). A. The embryonic heart starts pumping around day 22 and four chambers are apparent; four final chambers are defined during month two (pp. 516–517, Figs. 18.15–18.16). B. Congenital heart defects mostly are traced to month two of development (p. 518, Fig. 18.17). C. Age-related changes that affect the heart are hardening and thickening of the cusps of the heart valves and fibrosis of cardiac muscle (p. 519).