* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Richard I and Saladin

Church of the Holy Sepulchre wikipedia , lookup

Rhineland massacres wikipedia , lookup

Albigensian Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Nicopolis wikipedia , lookup

Northern Crusades wikipedia , lookup

Fourth Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Despenser's Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Second Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Kingdom of Jerusalem wikipedia , lookup

First Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Siege of Acre (1291) wikipedia , lookup

History of Jerusalem during the Kingdom of Jerusalem wikipedia , lookup

Military history of the Crusader states wikipedia , lookup

Barons' Crusade wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Hattin wikipedia , lookup

Third Crusade wikipedia , lookup

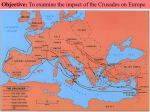

Teaching History with 100 Objects - Richard I and Saladin Teaching History with 100 Objects Richard I and Saladin These floor tiles were found at the site of Chertsey Abbey in Surrey. They show the English king, Richard I, spearing the Muslim leader Saladin with his lance during the Third Crusade. The scene was a popular depiction in medieval England and is found in wall paintings and manuscripts as well as on tiles. The Richard I and Saladin tiles form a good starting point for enquiries about the Third Crusade or the wider issues of crusading. From Chertsey Abbey, England Date AD 1250 – 60 Culture Medieval Britain Material Ceramic Dimensions Length: 17.1 cm Width: 10.4 cm Museum British Museum (Please always check with the museum that the object is on display before travelling) Teaching History with 100 Objects - Richard I and Saladin Teaching History with 100 Objects Richard I and Saladin About the object These tiles were found at the Benedictine abbey of Chertsey in Surrey. They were discovered accidentally in 1852 by the owner of the site, Samuel Grumbridge, when he uncovered fragments of a large tiled floor. The tiles depict a combat between Richard I and the Muslim leader Saladin. Richard and Saladin never actually encountered each other face to face, although their armies clashed several times during the course of the Third Crusade. However, since the end of the AD 1100s, the Third Crusade had been represented as a personal duel between the two leaders. By the later middle ages, manuscript images, wall paintings and tiles like those from Chertsey had helped fixed the image of Richard and Saladin locked in single combat in popular memory. Other tiles from Chertsey portray scenes from the story of Tristan and Isolde, which was the subject of one of the most famous popular prose romances of the AD 1200s. We know that Richard also featured as the hero of a romance in this period, so it is quite possible that the tiles were a literary reference. Fragments found close to the Richard and Saladin tiles contained letters spelling Richard’s name and other words, suggesting that an inscription surrounded them. In July 1187, Saladin’s forces defeated the armies of the crusader states at the Battle of Hattin. By the end of September 1187, Saladin had achieved his goal: the recapture of Jerusalem. For the first time in nearly ninety years the Muslims were in control of the Holy City. It was the shock of Saladin’s victories at Hattin and Jerusalem that prompted the Third Crusade. The crusade was led by the three most powerful monarchs in the Latin West: Richard I of England, Philip II of France and Frederick I of Germany. This potentially gave the crusade enormous strength, but things did not go well for the crusaders. Frederick and his armies travelled on an overland route to the Holy Land; in June 1190, the German king drowned while crossing a river. By the time Richard and Philip reached the crusader port of Acre in June 1191, a deep mistrust had developed between the two kings. They defeated Saladin’s forces at Acre, but Philip decided to abandon the crusade and returned to France. It was left to Richard to attempt the re-conquest of Jerusalem. Following a long and gruelling march in the summer heat of 1191, Richard’s forces defeated Saladin at the Battle of Arsuf on 7 September. The way to Jerusalem was now open. Richard made his first attempt to take Jerusalem during the winter of 1191 – 2, but the king doubted that his forces would be able to sustain a siege of the city and he abandoned the attack. The following summer he made a second attempt to take Jerusalem. Once again, Richard decided that the lack of water, the difficulty of supplying the army and Jerusalem’s formidable defences made a successful attack unlikely. On 4 July 1192, the Third Crusade collapsed. In September, the crusaders and Muslims signed a truce. Richard I refused to visit Jerusalem and therefore never met Saladin. Following the stalemate of the Third Crusade in 1192, the Christian West sent a number of crusades to Palestine, Syria and Egypt. All ended in failure. By 1291, with the fall of the crusader city of Acre, the Muslims’ victory was complete. The image on the Chertsey tiles is violent and shocking. This killing of Saladin by Richard I might be imagined, but it cannot be denied that the era of the crusades was characterised by periods of terrible conflict between Christians and Muslims. This is, however, only part of the story. During the 12th and 13th centuries there were long periods of peace. Trade flourished, ideas were exchanged, and artistic styles were copied and fused. Some historians have argued that a distinctive Crusader Art emerged which combined Western, Byzantine and Islamic elements. The peaceful exchange of knowledge, ideas and artistic styles continued into the later middle ages. More information The Richard and Saladin tiles http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pe_m la/c/chertsey_tiles.aspx A Tristan tile from Chertsey http://medievalromance.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/A_Tristan_tile_from_Chertsey _Abbey Richard I’s reign An overview Richard I’s reign and his involvement in the Third Crusade. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/richard_i_king.shtml In Our Time from BBC Radio 4 Melvin Bragg and guests discuss the Third Crusade in 2001. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00547ls The Long View from BBC Radio 4 The Crusades. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/longview/longview_20021029.shtml Interview with Thomas Asbridge Interview with Thomas Asbridge about his book The Crusades (2010). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q1ZrloO7o-A A medieval source The capture of the Holy Land by Saladin. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1187saladin.asp Crusader art A famous example of crusader art: The Melisende Psalter. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/sacredtexts/melispsalter.html BBC History of the wolrd in 100 objects Useful information about trading contacts between European and Islamic worlds. http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/2GL6QSA8SMmcMCtPg HQJsw Article on the Crusades Article on the Crusades in later western culture. http://www.library.rochester.edu/robbins/crusades Teaching History with 100 Objects - Richard I and Saladin Teaching History with 100 Objects Richard I and Saladin A bigger picture The Crusades are sometimes depicted as a period of incessant warfare between Christians and Muslims. However, across the 12th and 13th centuries, there were long periods of relative peace when trade flourished and artistic styles were exchanged. This selection of objects provides evidence of that trade and demonstrates some of the ways in which Muslim and Christian craftsmen were influenced by each other’s artistic traditions. Some figures hold Christian symbols; made in Mosul or Damascus; AD 1200s. See more See more: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_detail s.aspx?objectId=239122&partId=1&searchText=saladin&images=true&page=1 The seated figures are in Islamic style; the riders are in Christian; style from Syria; AD 1330 – 50. See more See more: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_detail s/collection_image_gallery.aspx?partid=1&assetid=37579&objectid=239363 Decorated with Christian symbols, but made by a Muslim glassmaker; made in Syria or Muslim Sicily; AD 1100s. See more See more: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_detail s.aspx?objectId=217275&partId=1 Horn with Islamic oaverll design, but figures in European style; from southern Italy; AD 1100s. See more See more: http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pe_mla/t/the_ borradaile_oliphant.aspx Perhaps from Saladin’s building works after his victory over the Crusaders. Notice the similarities to European Corinthian column capitals from Jerusalem; late AD 1100s. See more See more: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_detail s.aspx?objectId=234626&partId=1&images=true&museumno=1903,0220.4&pa ge=1 Teaching History with 100 Objects - Richard I and Saladin Teaching History with 100 Objects Richard I and Saladin Teaching ideas The Richard and Saladin tiles are a ready-made jigsaw. Print and cut up the tiles along the lines separating individual pieces. Students can work in pairs to do the jigsaw. This will force them to look carefully at the tiles and to begin discussing the different elements. When students have completed the jigsaw they can play a ‘think of a question’ game in teams of 4 or 5. Each team has a completed jigsaw or whole picture, if you prefer, a dice, a large sheet of paper and a marker pen. Within each team, students take it in turns to shake the dice and to think of a good question about the tiles beginning with the question word linked to a particular number: 1. What, 2. When, 3. Where, 4. Who, 5. How, 6.Why. Ask teams to pick their most interesting question and share these on the whiteboard. Then switch the focus to answering the questions. Are students certain about the answers to any questions? Can they make some good guesses about others? Tell students the story of the tiles: what they are, where they are from, what they show. Briefly explain who Richard and Saladin were and what happened on the Third Crusade. Explain that Richard and Saladin never met each other face to face. Tell students that after 1192 we find lots of images of Richard I spearing Saladin with his lance – in manuscripts, on wall paintings as well as on tiles. Look at the example from a manuscript in For the classroom. Can students suggest a reason for the use of this image? Compare the Chertsey tiles with the two examples of combat scenes made by Muslim artists in For the classroom. Which of the Muslim examples is most similar to the Cherstey scene? Explore other famous examples of tiles from medieval England. Search the British Museum website for tiles from Byland Abbey and for the Tring tiles. Compare these with the Chertsey tiles. Find out more about the use of tiles, their cost and the industry of tile-making. The title page of Fuller’s Historie of the Holy Warre in For the classroom offers an opportunity to study how the Crusades were represented in the AD 1600s. The images and inscriptions are quite legible and easy to make out. The Richard and Saladin tiles can be incorporated into different enquires on the Crusades: Does Richard I deserve to be remembered as a great crusader? Start with the tiles, then introduce students to different images of Richard I from the middle ages to the 12th century, all of which portray Richard as crusading hero – there are two examples in For the classroom. Challenge students to study the events of the Third Crusade and to make their minds up about Richard: how far was he the great crusader portrayed in the images? The enquiry could be structured around: 1. Richard’s background and his decision to take the cross in 1187; 2. the preparations Richard made for the crusade including the Saladin Tithe and his decision to travel by sea; 3. his journey to the Holy Land; 4. the Siege of Acre, march to Jaffa and battle of Arsuf; 5. Richard’s attempts to recapture Jerusalem. Students can collect ideas on a great crusader/bad crusader grid as they study the Third Crusade. The enquiry could conclude with a debate or a discursive essay. Challenging simplified history: what made the Crusades so complex? Incorporate the Richard and Saladin tiles into a broad enquiry which introduces students to the crusades and requires them to explore the complexities of this period of history. Structure your students’ study of the Crusades in chronological stages introducing each stage with the statements given below. 1. The motivation of the first crusaders: People joined the First Crusade to become rich 2. The First Crusade: The First Crusade succeeded because it had strong leaders 3. Life in the crusader states: Muslims and Christians in the crusader states were always in conflict 4. The Third Crusade: Richard I was a great crusader 5. Crusades of the 13th century: The crusader states ended because of Baybars Ask student to response to each statement with “That’s too simple!” They can then write paragraphs challenging each simple statement as they move through the enquiry. The crusader states: melting pot, medieval apartheid or messy mixture? In this enquiry students investigate the nature of the society that emerged in the crusader states during the 12th century, and, in particular, the ways in which Muslims and Christians related to each other. Did the westerners mingle harmoniously with the indigenous population of eastern Christians and Muslims? Did they live separately using their laws and military force to oppress the Muslim population? Or was the reality more a combination of assimilation and segregation? Students could investigate these issues by studying settlement patterns, crusader castles, trade, the writing of Usama ibn Munqidh and architecture. There could be a particular focus on works of art such as the Melisende Psalter and some of the objects in A bigger picture. Teaching History with 100 Objects - Richard I and Saladin Teaching History with 100 Objects Richard I and Saladin For the classroom The Chertsey tiles showing Richard and Saladin Download this picture Manuscript Source: en.wikipedia.org Richard and Saladin in a manuscript; from the AD 1200s. Visit the site http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Crusade#mediaviewer/File:RichardSaladin.jpg Battle in front of a town Painting by an Arab artist showing a battle in front of a town; from Egypt; AD 1100s. Download this picture Carved stone combat scene Source: discoverislamicart.org Carved stone combat scene; from Konya, Turkey; AD 1100s. Visit the site http://www.discoverislamicart.org/zoom.php?img=http://www.museumwnf.org/te achinghistory100.org/images/lo_res/objects/isl/tr/1/10/1.jpg Richard I in combat with Saladin An 1831 print showing Richard I in combat with Saladin. Download this picture Statue of Richard I Source: en.wikipedia.org Statue of Richard I outside the Palace of Westminster, London. Visit the site http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_I_of_England#mediaviewer/File:Richard_the_f irst.jpg Title page for The Historie of the Holy Warre Title page for The Historie of the Holy Warre by Thomas Fuller; first published 1639. The portraits at the top are of Godfrey de Bouillon, a leader of the First Crusade, and Saladin. Download this picture Map of crusader states in 1190 Source: en.wikipedia.org Visit the site http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crusader_States_1190.svg Epitome of Chronicles Source: bl.uk Richard I (top right) and other English kings in Epitome of Chronicles by Matthew Paris; 1255. Visit the site http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/illmanus/cottmanucoll/r/largeimage75081 .html Outside the classroom Here is a selection of museums with relevant collections. Chertsey Museum Source: stpeterschertsey.org Visit the site http://www.stpeterschertsey.org/abbey/ca3.htm Royal Armouries, Leeds Source: royalarmouries.org Visit the site http://www.royalarmouries.org/home British Museum Source: britishmuseum.org Visit the site http://www.britishmuseum.org