* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download BALLOON VALVULPLASTY OF PULMONIC STENOSIS

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

History of invasive and interventional cardiology wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Echocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Cardiothoracic surgery wikipedia , lookup

Mitral insufficiency wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Aortic stenosis wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

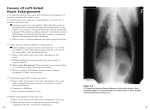

Veterinary Cardiorespiratory Centre Martin Referral Services, Thera House, 43 Waverley Road, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 1JL Tel: 01926 863445 INFORMATION SHEET - VETS BALLOON VALVULOPLASTY OF PULMONIC STENOSIS Indications Balloon valvuloplasty is indicated when there are clinical signs (symptoms) of forward heart failure, or right sided congestive heart failure, attributable to the pulmonic stenosis. In the absence of obvious clinical signs the following are also indications: The trans-stenotic pressure gradient exceeds 80mmHg. There is dynamic right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (also warrants beta blockers) There is severe right ventricular hypertrophy with flattening of the ventricular septum Outcome The Veterinary Cardiorespiratory Centre is one of the few specialist centres in the UK to regularly perform this procedure. This is one of the more difficult interventions and better results will be achieved with experienced veterinary cardiologists. The success rate varies in relation to the pathology of the stenosis, ie. commissural fusion, dysplasia or hypoplasia. However as a guideline in our experience >85% of cases will show a significant clinical improvement with a 40 - 60% drop in the pressure gradient through the stenosis. The procedure is not without risk and a small number of patients (approx. 5 - 7%) do not survive anaesthesia and surgery. Subvalvular stenosis, such as seen in Bulldogs, does not respond as well. Complications Aberrant coronary arteries can be present, particularly in Bulldogs, that would be a contraindication to balloon dilatation (see later). Where this is suspected, coronary angiograms will also be performed at the time of cardiac catheterisation (which will additionally require arterial catheterisation via the femoral artery). It’s presence then precludes proceeding to balloon dilatation. A patent foramen ovale is not uncommon; if this is reverse shunting (ie. right to left) an echo-contrast study should reveal this and the PCV also measured. A reverse shunting defect increases the anaesthetic complications, although in severe cases this is a risk that has to be taken. Arrhythmias are not uncommon with severe pulmonic stenosis, in particular during the passing of relatively large catheters through the heart during surgery. Pre-medication with beta blockers prior to surgery, in our experience, appears to reduce the incidence of arrhythmias and anaesthetic complications. Prior to surgery It is preferable if dogs are medicated with beta blockers before referral and these should normally be continued until a follow-up scan some months later. propranolol: 0.3 to 0.5mg/kg tid, or atenolol: 0.3 - 0.5mg/kg bid The dog should be free of any infections especially pyodermas and skin parasites - if present these should be treated before surgery can proceed. Post surgery follow-up Sutures from the left jugular area (or right femoral area) are due for removal 8 to 10 days post surgery. Beta blockers should be continued (in many cases) until a follow-up scan is performed in approximately 6 months time. References Martin M W S., Godman M, Luis Fuentes V, Clutton R E, Haigh A L and Darke P G G. (1992) Assessment of balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty in six dogs. Journal of Small Animal Practice 33, 443 - 449. Stafford Johnson MJ & Martin M (2003) Balloon valvuloplasty in a cat with pulmonic stenosis. JVIM 17: 928-930 Stafford Johnson MJ & Martin MWS (2004). Results of balloon valvuloplasty in 40 dogs with pulmonic stenosis. JSAP, 45, 148-153 Stafford Johnson MJ & Martin MWS, Edwards D, French A & Henley W. (2004). Pulmonic stenosis in dogs: balloon valvuloplasty improves clinical outcome. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 18: 656-662 A review of pulmonic stenosis in small animals ~ Mike Martin Pathology of pulmonic stenosis The most common form of pulmonic stenosis in dogs and cats is valvular (supravalvular and subvalvular stenosis are rare), which is the form for which balloon valvuloplasty is appropriate. The valvular form consists of three types: 1. Fusion of the cusp - thus they do not open fully 2. Valve dysplasia - abnormal morphology with thickening of the cusps 3. Narrowed annulus In dogs and cats, these three types of stenosis occur in differing proportions and it is not possible to identify clearly which type predominates by currently available diagnostics. Cusp fusion is the type that responds best to ballooning and it is generally believed this type predominates in the majority of dogs, which is also our experience. Aberrant coronary arteries In Bulldogs, there have been reports of aberrant coronary arteries in association with the pulmonic stenosis - we have seen a few such Bulldogs, but also seen similar complications in a Shih Tzu and a Staffie cross bred dog. In this condition the left coronary artery has not formed and instead the left ventricle is fed by an aberrant branch of the right coronary artery. However this aberrant branch encircles the subvalvular pulmonic stenosis, thus either ballooning or traditional surgery (eg. patch graft technique) would result in rupture of the coronary and death. Pathophysiology The stenosis restricts cardiac output, in proportion to severity. The right ventricular myocardium must generate increased strength of contractility and chamber pressure to sustain cardiac output through the stenosis resulting in an increase in blood flow velocity through the stenosis. The right ventricular myocardium hypertrophies in proportion to the severity of the stenosis. The hypertrophy is concentric causing a marked change in shape of the right ventricle for which the tricuspid valve cannot compensate. The valve therefore can become incompetent in many cases, leading to right atrial dilation and right sided congestive heart failure. The ventricular hypertrophy can result in additional obstruction to blood flow through the right ventricular outflow tract during systole (dynamic outflow tract obstruction). History and Clinical Signs In the majority of cases a systolic murmur may be the only finding. This is usually heard maximally over the left heart base and on the right side of the thorax and close to the sternum. In moderately or severely affected dogs, there may be a history of exercise intolerance, right sided congestive heart failure or syncope. ECG There is a right ventricular enlargement patternin >90% of cases Ventricular tachydysrhythmias (ventricular premature complexes, ventricular tachycardia) may be present in more severely affected cases. Radiography Right ventricular enlargement is often seen (enlargement and rounding of the right heart border on the lateral and DV views). On the DV view, a post-stenotic bulge in the pulmonary artery may be evident but its size does not appear to correlate with severity. Right atrial enlargement may be present in cases with tricuspid regurgitation, often better appreciated on the DV view. Echocardiography 2-D echocardiography may visualise the valvular pulmonic stenosis as abnormally thickened valves particularly when there is a severe lesion, but is often difficult to reliably and accurately appreciate. The post-stenotic bulge is sometimes seen and the right ventricle is often seen to be hypertrophied. Right atrial dilation may be evident. Subvalvular stenosis with aberrant coronaries It can sometimes be difficult to reliably distinguish subvalvular stenosis from valvular stenosis. Subvalvular stenosis is the type that can be associated with aberrant coronaries. This type of stenosis often appears to have a very narrowed annulus compared to the more usual valvular stenosis. In addition, sometimes an abnormal coronary artery can be appreciated on the right parasternal long axis view maximised to show the aorta. The aberrant coronary is sometimes seen to course in an unusual direction from the sinus of valsalva (septal side). In short axis view it can sometimes also be appreciated at the same level of the stenosis and appears to course around it. Doppler echocardiography is currently the definitive means of diagnosis. It will demonstrate an increase in velocity through the stenosis (V2) compared to the velocity proximal to it (V1), ie. there is a step up in velocity. The pressure gradient is proportional to the velocity, which can be estimated from the modified Bernoulli equation [the pressure gradient = 4 (V2 - V1)2 ]. As a guide a pressure gradient (PG) <50mmHg is considered mild, a PG between 50 and 100mmHg is moderately severe and a PG >100mmHg is severe. If there is dynamic outflow tract obstruction this is best seen on spectral Doppler as an exponential increase in velocity. In this situation estimating the true PG becomes difficult as V1 is not elevated and accurate measurement of this is difficult. If there is tricuspid valve incompetence the PG between the right ventricle and atrium can also be estimated - this provides a second method in which right ventricular pressure can be measured. Treatment Treatment is usually only required in moderately or severely affected cases and those producing clinical signs. If there is congestive heart failure this is controlled with diuretics (eg. frusemide) and ACE inhibitors. Primary treatment of ventricular dysrhythmias may be managed with anti-arrhythmics such as beta blockers. Balloon valvuloplasty has been shown to be associated with good success in dogs resulting in a long term imporvement in 85% of cases. Indications for balloon valvuloplasty 1. The presence of clinical signs (symptoms) 2. Doppler derived trans-stenotic pressure gradient > 80mmHg 3. Dynamic right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (also warrants beta blockers) 4. Severe right ventricular hypertrophy with flattening of the ventricular septum Prognosis A prognosis can be offered based upon severity, assessed by Doppler echocardiography. A dog with a mild stenosis (pressure gradient less than 40mmHg) will usually live a full and normal life. Dogs with a more severe stenosis may develop clinical signs in the second half of life, and those with a pressure gradient in excessive of 80mmHg usually do so within the first few years of life. The presence of right sided congestive failure warrants a more guarded prognosis. REFERENCES Bonagura, J.D. (1989) Congenital heart disease. In: Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 3rd edn. Ed: S.J. Ettinger. W.S. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. Martin, MWS, Godman, M, Luis Fuentes, V, et al (1992) Assessment of balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty in six dogs. Journal of Small Animal Practice 33: 443. Patterson, D.F. and others (1981). Hereditary dysplasia of the pulmonic valve in beagle dogs. Am. J. Cardiology 47, 631.