* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download (V4) Increasing Exclusion: The Pauli Exclusion Principle and Energy

Renormalization group wikipedia , lookup

Molecular Hamiltonian wikipedia , lookup

Matter wave wikipedia , lookup

Ferromagnetism wikipedia , lookup

Renormalization wikipedia , lookup

Particle in a box wikipedia , lookup

X-ray fluorescence wikipedia , lookup

Quantum electrodynamics wikipedia , lookup

Rutherford backscattering spectrometry wikipedia , lookup

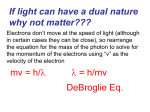

Wave–particle duality wikipedia , lookup

Auger electron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Hydrogen atom wikipedia , lookup

Atomic orbital wikipedia , lookup

Tight binding wikipedia , lookup

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Atomic theory wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation wikipedia , lookup