* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Grades 6-8 grammar alignment and common definitions Idea

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

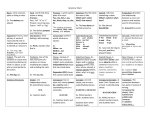

Grades 6-8 grammar alignment and common definitions Idea: Create a pre and post test to be used to assess growth in grammar skills (beginning of year and end of year). One test that students take each year. 6th Pronouns: Teach why we use pronouns Teach the different pronouns (subjective, objective, possessive, and intensive) Students should be able to identify pronouns in their writing and others' writings Students should be able to recognize and correct vague and inappropriate shifts in pronouns in their own writing. Punctuation: Teach what an appositive is (aka interrupter or parenthetical element) Discuss the different effects commas, dashes, and parentheses add to writing Students should be able to use commas, dashes and parentheses accurately in their writing Spelling: Spell correctly Knowledge and language: Teach sentence fluency (sentence lengths, beginnings of sentences, varying the subject predicate order) Students use a variety of sentences in their writing Teach style and tone to maintain consistency in style and tone Students should demonstrate consistency in style and tone within their writing 7th Phrases and Clauses (this should be taught prior to sentence structure) Teach what a phrase and a clause is and their function Students should be able to define and identify phrases and clauses Teach what dangling modifiers and misplaced are and how to correct them Students should be able to recognize dangling and misplaced modifiers and be able to correct them in their own writing Sentence Structure Teach the different types of sentences (simple, compound, complex, and compound/complex) Teach how to punctuate these types of sentence (specifically commas) Teach how to combine ideas into one sentence and when it's effective to use the different types of sentences Students should be able to recognize the different types of sentences Students should be able to write with varying sentence types to clearly get their point across Punctuation Teach when to use a comma when you have coordinate adjectives and the difference between coordinate adjectives and non-coordinate adjectives Students should be able to write using adjectives and punctuate coordinate adjectives with a comma Spelling Spell correctly Knowledge and language (teach this with the sentence structure section) Teach the difference between being concise and being wordy and redundant Students should be able to use what they learned about sentence structure and phrases and clauses in order to become a more concise writer 8th Verbs and Verb Tense Teach what active and passive voice is and the difference between the two Students should be able to identify active and passive voice in writing Students should be able to write using verbs of both voices depending on the type of writing they are doing (voice needs to be consistent throughout writing) Teach indicative, imperative, interrogative, conditional, and subjunctive mood to show particular effects writers use Students should be able to identify indicative, imperative, interrogative, conditional, and subjunctive mood in writing and discuss the effects of the writing Verbals Teach what a gerund, participles, and infinitives is, as well as the function (function = for effect and sentence variety) Students should be able to identify and explain the function of the 3 types of verbals in sentences Punctuation Teach rules for commas, ellipsis, and dashes Students should be able to use commas, ellipsis, and dashes accurately in their writing Spelling Spell correctly Knowledge and language: (should be covered when teaching verbs, verb tense and verbals) Grade 6 6-12 Grammar Common Definitions Pronouns L.6.1a—ensure pronouns in proper case (subjective, objective possessive) A subjective pronoun acts as the subject of a sentence—it performs the action of the verb. The subjective pronouns are he, I, it, she, they, we, and you. He spends ages looking out the window. After lunch, she and I went to the planetarium. An objective pronoun acts as the object of a sentence—it receives the action of the verb. The objective pronouns are her, him, it, me, them, us, and you. Cousin Eldred gave me a trombone. Take a picture of him, not us! A possessive pronoun tells you who owns something. The possessive pronouns are hers, his, its, mine, ours, theirs, and yours. The red basket is mine. Yours is on the coffee table. L.6.1b—use intensive pronouns An intensive pronoun is a pronoun used to add emphasis to a statement; for example, "I did it myself." L.6.1c—recognize/correct inappropriate shifts in pronoun number and person 1. Agree in number If the pronoun takes the place of a singular noun, you have to use a singular pronoun. Ex: If a student parks a car on campus, he or she has to buy a parking sticker. (NOT: If a student parks a car on campus, they have to buy a parking sticker.) 2. Agree in person If you are writing in the "first person" (I), don't confuse your reader by switching to the "second person" (you) or "third person" (he, she, they, it, etc.). Similarly, if you are using the "second person," don't switch to "first" or "third." Ex: When a person comes to class, he or she should have his or her homework ready. (NOT: When a person comes to class, you should have your homework ready.) L.6.1d—recognize/correct vague pronouns Refer clearly to a specific noun. Don't be vague or ambiguous. NOT: Although the motorcycle hit the tree, it was not damaged. (Is "it" the motorcycle or the tree?) NOT: I don't think they should show violence on TV. (Who are "they"?) NOT: Vacation is coming soon, which is nice. (What is nice, the vacation or the fact that it is coming soon?) Punctuation L.6.2a—use punctuation (commas, parentheses, dashes) to set off nonrestrictive/parenthetical elements An interrupter, or parenthetical element, is any sentence element that interrupts the forward movement of a clause. An interrupter is set off from the clause it interrupts by parenthetical punctuation. EXAMPLES: Commas ~Take, for example, the way Linda responded to being accused of bias. ~That explanation, as I have already said, doesn't really hold water. ~You should, nevertheless, continue your efforts despite this recent disappointment. ~He cannot, however, hope to defeat a popular incumbent. Dashes ~There is no way--and no particular reason--to gauge popular interest in such an approach. ~The mythographer Joseph Campbell--who visited this campus in the 1980s, by the way--is perhaps best known for his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Parentheses ~The last person who leaves (that is, if anyone ever manages to get out of here at all) needs to make sure all the lights are out and the furniture is put back in its proper place. ~The War of the Worlds (this isn't the first time it has been made into a movie, you know) is based on a well-known science fiction novel. Grade 7 Phrases and Clauses L.7.1a—Explain the function of phrases and clauses in general and their function in specific sentences. English Phrases are a word or group of words used as a single value An English word or group of words used as a single value (without either a subject or predicate) are called phrases. English phrases tend to be larger than individual words and are usually considered as expansions of an individual word. English phrases are smaller than clauses or sentences as they do not have subjects and predicates or subjects and verbs. A clause is an organized group of English Words An English clause is an organized group of English words with a subject and predicate. A main clause is an independent clause which can stand alone as a complete sentence. Independent clauses also called principal or main clauses can form sentences. L.7.1c—Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. You have a certain amount of freedom in deciding where to place your modifiers in a sentence: We rowed the boat vigorously. We vigorously rowed the boat. Vigorously we rowed the boat. However, you must be careful to avoid misplaced modifiers -- modifiers that are positioned so that they appear to modify the wrong thing. In fact, you can improve your writing quite a bit by paying attention to basic problems like misplaced modifiers and dangling modifiers. Misplaced Words In general, you should place single-word modifiers near the word or words they modify, especially when a reader might think that they modify something different in the sentence. Consider the following sentence: [WRONG] After our conversation lessons, we could understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors from Madrid easily. Do we understand the Spanish easily, or do the visitors speak it easily? This revision eliminates the confusion: [RIGHT] We could easily understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors from Madrid. It is particularly important to be careful about where you put limiting modifiers. These are words like "almost," "hardly," "nearly," "just," "only," "merely," and so on. Many writers regularly misplace these modifiers. You can accidentally change the entire meaning of a sentence if you place these modifiers next to the wrong word: [WRONG] Randy has nearly annoyed every professor he has had. (he hasn't "nearly annoyed" them) [WRONG] We almost ate all of the Thanksgiving turkey. (we didn't "almost eat" it) [RIGHT] Randy has annoyed nearly every professor he has had. [RIGHT] We ate almost all of the Thanksgiving turkey. Sentence Structure L.7.1b—choose among simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to signal differing relationships among ideas. A simple sentence has the most basic elements that make it a sentence: a subject, a verb, and a completed thought. Examples of simple sentences include the following: Joe waited for the train. "Joe" = subject, "waited" = verb Mary and Samantha arrived at the bus station before noon and left on the bus before I arrived. "Mary and Samantha" = compound subject, "arrived" and "left" = compound verb A compound sentence refers to a sentence made up of two independent clauses (or complete sentences) connected to one another with a coordinating conjunction. Coordinating conjunctions are easy to remember if you think of the words "FAN BOYS": For And Nor But Or Yet So Examples of compound sentences include the following: Joe waited for the train, but the train was late. I looked for Mary and Samantha at the bus station, but they arrived at the station before noon and left on the bus before I arrived. complex sentence is made up of an independent clause and one or more dependent clauses connected to it. A dependent clause is similar to an independent clause, or complete sentence, but it lacks one of the elements that would make it a complete sentence. Examples of dependent clauses include the following: because Mary and Samantha arrived at the bus station before noon while he waited at the train station after they left on the bus Dependent clauses such as those above cannot stand alone as a sentence, but they can be added to an independent clause to form a complex sentence. Dependent clauses begin with subordinating conjunctions. Below are some of the most common subordinating conjunctions: after although as because before even though if since though unless until when whenever whereas wherever while A complex sentence joins an independent clause with one or more dependent clauses. A compound-complex sentence is made from two independent clauses and one or more dependent clauses. Some examples: 1. Although I like to go camping, I haven't had the time to go lately, and I haven't found anyone to go with. independent clause: "I haven't had the time to go lately" independent clause: "I haven't found anyone to go with" dependent clause: "Although I like to go camping... " Punctuation L.7.2a—use a comma to separate coordinate adjectives Separate coordinate adjectives—those that apply equally to the noun they modify—with commas. � The twisting, muddy road led to a shack in the woods. The adjectives twisting and muddy both apply equally to the noun road, so a comma should separate them. Not all adjectives that precede a noun are coordinate adjectives. � The cracked bathroom mirror reflected his face. The adjectives cracked and bathroom are not coordinate because cracked modifies bathroom mirror, not just mirror. Do not separate adjectives like these with a comma. You can usually determine whether adjectives are coordinate by inserting and between them. If the sentence makes sense with the and, the adjectives are coordinate, so separate them with commas. Grade 8 Verbs and Verb Tense L.8.1b—form and use verbs in the active/passive voice Active Form In active sentences, the thing doing the action is the subject of the sentence and the thing receiving the action is the object. Most sentences are active. [Thing doing action] + [verb] + [thing receiving action] Examples: The professor teaches the students (professor = subject doing the action) (teacher = verb) (the students = object receiving the action) John washes the dishes. (John = subject doing action) (washes = verb) (the dishes = object receiving the action) Passive Form In passive sentences, the thing receiving the action is the subject of the sentence and the thing doing the action is optionally included near the end of the sentence. You can use the passive form if you think that the thing receiving the action is more important or should be emphasized. You can also use the passive form if you do not know who is doing the action or if you do not want to mention who is doing the action. [Thing receiving action] + [be] + [past participle of verb] + [by] + [thing doing action] Examples: The students are taught by the professor. (The students = subject receiving action) (are taught = passive verb) The dishes are washed by John. (The dishes = subject receiving action) (are washed = passive verb) (by John = doing action) L.8.1c—form and use verbs in the indicative, imperative, interrogative, conditional, and subjunctive mood. Mood Mood is an indication of the purpose or intent of the sentence (its manner of use). English verbs have three moods- the declarative (or indicative), the subjunctive and the imperative. Other writers may have a separate mood category for conditional or interrogative sentence forms. In this manual, the interrogative mood (questions) is considered part of the declarative mood and the conditional is considered part of the subjunctive mood. A. Declarative or Indicative Mood The declarative or indicative mood is the simplest and most basic mood. It is used to make statements and to ask questions. The overwhelming majority of verb use is in the indicative, which may be considered the “normal” form of verbs, with the subjunctive and imperative as an “exceptional” form of verbs. I think I’ll go to the park. I thought you didn’t like pancakes? Do you see him? I am cooking fish for dinner tonight. He was singing in the shower. He’s a veterinarian. B. Subjunctive Mood The subjunctive mood is used to express a wish or a condition which is contrary to fact. It is often found in if- then statements. It is typically marked in the present tense by the auxiliary ‘were’ or ‘if + pronoun + were’ + the present participle of the verb’. Were I eating, I would sit. If he were waiting, he would pace. If I were going, I would give you a lift. The subjective is also used in verb clauses that begin with ‘that’ following verbs that request, demand, or recommend. My mother asked that I do the dishes. She insisted that I buy her flowers for Valentines Day. The IRS requires that all wage earners submit income tax returns. C. Imperative Mood The imperative mood is used for commands, requests, or instructions. The imperative mood is found only in the present tense, second person. The subject is always the pronoun ‘you’, but the word ‘you’ is usually implied and is seldom in the sentence. (You) Listen! (You) Sit! Eat! Stop that! D. Conditional Mood So go the first two stanzas of Lee Hays and Pete Seeger's folk tune, "If I had a hammer," one of the most famous tunes and lyrics in the history of American song. The grammar of the lyrics uses what is called the conditional. The writer expresses an action or an idea (hammering out danger and warning and love) that is dependent on a condition, on something that is only imagined (having a hammer or a bell — or, in the next stanza, a song). In this situation, the lyricist imagines what he would do if he "had a hammer" — now, in the present. He might also have imagined what he would have done if he "had had a hammer," in the past, prior to something else happening: "If I had had a hammer, I would have hammered a warning." Verbals L.8.1a—Explain the function of verbals (gerrunds, participles, infinitives) in general and their function in particular sentences A gerund is a verbal that ends in -ing and functions as a noun. The term verbal indicates that a gerund, like the other two kinds of verbals, is based on a verb and therefore expresses action or a state of being. However, since a gerund functions as a noun, it occupies some positions in a sentence that a noun ordinarily would, for example: subject, direct object, subject complement, and object of preposition. Gerund as subject: Traveling might satisfy your desire for new experiences. (Traveling is the gerund.) The study abroad program might satisfy your desire for new experiences. (The gerund has been removed.) Gerund as direct object: They do not appreciate my singing. (The gerund is singing.) They do not appreciate my assistance. (The gerund has been removed) Gerund as subject complement: My cat's favorite activity is sleeping. (The gerund is sleeping.) My cat's favorite food is salmon. (The gerund has been removed.) Gerund as object of preposition: The police arrested him for speeding. (The gerund is speeding.) The police arrested him for criminal activity. (The gerund has been removed.) A participle is a verbal that is used as an adjective and most often ends in -ing or -ed. The term verbal indicates that a participle, like the other two kinds of verbals, is based on a verb and therefore expresses action or a state of being. However, since they function as adjectives, participles modify nouns or pronouns. There are two types of participles: present participles and past participles. Present participles end in -ing. Past participles end in -ed, -en, -d, -t, -n, or -ne as in the words asked, eaten, saved, dealt, seen, and gone. The crying baby had a wet diaper. Shaken, he walked away from the wrecked car. The burning log fell off the fire. Smiling, she hugged the panting dog. An infinitive is a verbal consisting of the word to plus a verb (in its simplest "stem" form) and functioning as a noun, adjective, or adverb. The term verbal indicates that an infinitive, like the other two kinds of verbals, is based on a verb and therefore expresses action or a state of being. However, the infinitive may function as a subject, direct object, subject complement, adjective, or adverb in a sentence. Although an infinitive is easy to locate because of the to + verb form, deciding what function it has in a sentence can sometimes be confusing. To wait seemed foolish when decisive action was required. (subject) Everyone wanted to go. (direct object) His ambition is to fly. (subject complement) He lacked the strength to resist. (adjective) We must study to learn. (adverb) Be sure not to confuse an infinitive—a verbal consisting of to plus a verb—with a prepositional phrase beginning with to, which consists of to plus a noun or pronoun and any modifiers. Infinitives: to fly, to draw, to become, to enter, to stand, to catch, to belong Prepositional Phrases: to him, to the committee, to my house, to the mountains, to us, to this address Punctuation L.8.2a—Use punctuation (comma, ellipsis, dash) to indicate a pause or break. AND L.8.2b—use an ellipsis to indicate an ommission Using An Ellipsis to Show an Omission In formal writing, the most common way to use an ellipsis is to show that you’ve omitted words. For example, if you're quoting someone and you want to shorten the quote, you use ellipses to indicate where you've dropped words or sentences. Here's a quote from the book Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens: “I cannot help it; reason has nothing to do with it; I love her against reason.” Now far be it from me to edit Dickens, but if I were a journalist under a tight word limit looking at that quotation, I'd be tempted to shorten it to this: “I cannot help it . . . I love her against reason.” That middle part—“reason has nothing to do with it”—seems redundant, and taking it out doesn't change the meaning. Dot-dot-dot and it's gone, which saves seven words. Clearly, literature and journalism are not the same thing. Here’s another example from a recent review of the movie “Get Him to the Greek.” In the Contra Costa Times, Randy Myers writes, “The outrageous ‘Greek’ works better than ‘Funny People’ at least in part because Apatow, who tends to make films that meander too much, hands over writing and directing to a protégé.” If I wanted to quote Myers, and I had limited space, I could use an ellipsis to shorten the quotation: “The outrageous ‘Greek’ works better than ‘Funny People’ . . . because Apatow hands over writing and directing to a protégé. A dash is a horizontal line that shows a pause or break in meaning, or that represents missing words or letters. Note that dashes are rather informal and should be used carefully in writing. Dashes are often used informally instead of commas, colons and brackets. A dash may or may not have a space on either side of it. Do not confuse a dash (—) with a hyphen (-), which is shorter. 1. Use a dash to show a pause or break in meaning in the middle of a sentence: My brothers—Richard and John—are visiting Hanoi. (Could use commas.) In the 15th century—when of course nobody had electricity—water was often pumped by hand. (Could use brackets.) 2. Use a dash to show an afterthought: The 1st World War was supposed to be the world's last war—the war to end war. I attached the photo to my email—at least I hope I did! 3. Use a dash like a colon to introduce a list: There are three places I'll never forget—Paris, Bangkok and Hanoi. Don't forget to buy some food—eggs, bread, tuna and cheese. Commas Comma Conundrums: When They Clarify, When They Confuse Commas help you to communicate to your reader when specific words or ideas should be linked together and when they should be considered separately. The break between two thoughts separated by a comma is not as strong as those separated by a period or a semi-colon; it is only a slight mental pause. Putting a comma where it doesn’t belong creates an unintended break in meaning; using a comma where a period or semi-colon should be used ties ideas together too closely. Beware of popular myths of comma usage: MYTH: Long sentences need a comma. A really long sentence may be perfectly correct without commas. The length of a sentence does not determine whether you need a comma. MYTH: You should add a comma wherever you pause. Where you pause or breathe in a sentence does not reliably indicate where a comma belongs. Different readers pause or breathe in different places. MYTH: Commas are so mysterious that it's impossible to figure out where they belong! Some rules are flexible, but most of the time, commas belong in very predictable places. You can learn to identify many of those places by using the tips in this handout. Basic Rules for Comma Use 1. Use commas to separate words, phrases, or clauses in a series. The words can be nouns, adjectives, or verbs. The secret recipe for the superdelicious drink I invented includes vodka, grapefruit juice, raspberries, a splash of rye, and ketchup. The dog ran through the park, grabbed the Frisbee from the boy, and jumped in the lake. That small, dark closet definitely houses vampires. We came, we saw, we ate, and we left. All of these examples use the serial comma, which means they include a comma before the last item in the series. Sometimes the serial comma is absent in magazines and newspapers, but it is generally a good idea to use it in formal writing. It often helps to clarify the relationship between the items in a series, too. For example, consider this book dedication: To my parents, the Pope and Mother Teresa (Is it dedicated to these three people? Or are the parents of the author the Pope and Mother Teresa? Imagine the scandal!) 2. Use commas to separate adjectives in a series if you could replace the comma with “and.” The healthy, delicious food available on this campus reflects well on the school’s interest in student health and well-being. The seven senior girls live in a giant three-story house. (no comma because you wouldn’t say “giant and three-story house” or “seven and senior girls”) 3. Use commas before coordinating conjunctions that join two independent clauses. There are two key points: A) Never put a comma after a coordinating conjunction—only before. (FANBOYS is a handy mnemonic device for remembering the coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So.) Yes: I went to see Samantha perform in the school play, but she did not return the favor by coming to my recital. No: Samantha claimed that she got lost on the way, but, I know that she actually went to the movies that afternoon. B) The clauses separated by commas should be independent: they should each be able to stand alone as sentences. Yes: Elephants may never forget what they know, but how much do they really know to begin with? No: Mark went to the bank, and took out some money to lend me. If you don’t have FANBOYS between the two complete and separate thoughts, using a comma alone causes a "comma splice" or "fused sentence" (some instructors may call it a run-on). Some readers (especially professors) will consider this a serious error. 4. Use commas to set off introductory elements, especially if they are long. An introductory element is a word or phrase that precedes the main subject-verb sentence. Here are several examples: First, I will argue that men are more closely related to dinosaurs than women. After that argument has been made, I will move into a broader discussion of reptiles. A fierce academic debater, Dr. Atticus was surprised when she was unable to persuade her husband to do the dishes. What’s wrong with this one? After retiring my wife, my parents, our neighbors, and I plan to travel across the country. 5. Use commas to set off non-essential elements of the sentence. My niece, wearing a yellow jumpsuit, is playing in the living room. The Green party candidate, who had the least money, lost the election. Professor Benson, grinning from ear to ear, announced that the exam would be tomorrow. Tom, the captain of the team, was injured in the game. She was, however, too tired to make the trip. Do not use commas to set off essential elements of the sentence, such as clauses beginning with that (relative clauses). That clauses after nouns are (usually) essential. That clauses following a verb expressing mental action are always essential. That clauses after nouns: The book that I borrowed from you is excellent. The apples that fell out of the basket are bruised. That clauses following a verb expressing mental action: She believes that she will be able to earn an A. I contend that it was wrong to mislead her. They wished that warm weather would finally arrive. 6. Use a comma near the end of a sentence to separate contrasted coordinate elements or to indicate a distinct pause or shift. He was merely ignorant, not stupid. The chimpanzee seemed reflective, almost human. 7. Use a comma to shift between the main discourse and a quotation. John said without emotion, "I'll see you tomorrow." "I was able," she answered, "to complete the assignment." In 1848, Marx wrote, "Workers of the world, unite!" Comma Abuse Putting a comma in the wrong place can break a sentence into illogical segments or confuse readers with unnecessary and unexpected pauses. 1. Don't use a comma to separate the subject from the verb. An eighteen-year old in California, is now considered an adult. (incorrect) The most important attribute of a ball player, is quick reflex actions. (incorrect) 2. Don't put a comma between the two verbs or verb phrases in a compound predicate. We laid out our music and snacks, and began to study. (incorrect) I turned the corner, and ran smack into a patrol car. (incorrect) 3. Don't put a comma between the two nouns, noun phrases, or noun clauses in a compound subject or compound object. The music teacher from your high school, and the football coach from mine are married. (incorrect: compound subject) Jeff told me that the job was still available, and that the manager wanted to interview me. (incorrect: compound object) 4. Don't put a comma after the main clause when a dependent (subordinate) clause follows it, except for cases of extreme contrast. She was late for class, because her alarm clock was broken. (incorrect) The cat scratched at the door, while I was eating. (incorrect) She was still quite upset, although she had won the Oscar. (correct: extreme contrast)