* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download tropical medicine

Self-experimentation in medicine wikipedia , lookup

Mosquito control wikipedia , lookup

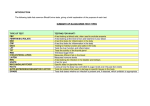

Epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Focal infection theory wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Compartmental models in epidemiology wikipedia , lookup

Diseases of poverty wikipedia , lookup

Public health genomics wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup