* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download SECESSION and UNION - The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

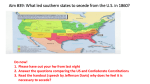

Missouri secession wikipedia , lookup

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup