* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CW Handbook Front Matter.vp

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Texas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Lost Cause of the Confederacy wikipedia , lookup

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

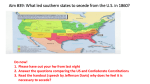

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Publisher’s Preface Why the Civil War, and Why Do We Study it? There is a simple reason why the Civil War remains popular in books and movies, and why large numbers of tourists visit its battlefields year after year. Except for our founding Revolution, 1861-1865 represents the defining event in our nation’s history, and one of the major events in world history. Bloody war was needed if important constitutional questions were to be settled. The immediate issue revolved around secession. Could a state secede? Was such a thing allowed under the U.S. Constitution, as many believed and openly advocated, or was the act of a state or group of states seeking to leave the Union unconstitutional? Many in the South argued yes. The American Revolution begun in 1775 was not a revolution at all, some explained, but the secession of part of the home country from another segment. Many people are surprised to learn that it was New England, and not the Southern states, that first raised the specter of secession. States in the Northeast threatened to leave the Union several times, beginning in 1803 when Thomas Jefferson arranged the Louisiana Purchase, again near the end of the War of 1812, and yet a third time more than thirty years later when New England politicians screamed over the annexation of Texas as a slave state. When South Carolina threatened to withdraw from the Union over economic issues, President Andrew Jackson threatened to invade the state with Federal troops. South Carolina rattled the sword again in 1850, and finally made good on its threats by withdrawing from the Union in December of 1860. The shocking declaration started a landslide that carried several other states with her. War followed in her wake. Only bayonets and bloodshed decided the constitutional issue: the right of secession was not to be found inside the four corners of the Constitution. Why did Southern states secede? The first eighty years of our existence grounded our original states and those created thereafter in two diametrically opposite philosophical systems: slave and free. Could a country erected on the brick and mortar of individual freedom and self-determination continue with a large percentage of its population in chains? The war decided it could not. Many reasons were raised then, and are still argued to this day, in an effort to justify separation, from “States’ Rights”—and all that entails—to tariff x The New Civil War Handbook issues, economic matters, and social and cultural differences. Each was a lightening rod for argument and war because each, either directly or indirectly, was tied to the institution of slavery. “[It] is fair to say that had there been no slavery there would have been no war,” wrote a prominent Confederate general once the fighting ended. “Slavery was undoubtedly the immediate fomenting cause of the woeful American conflict.” The country decided by force of arms that it would no longer tolerate black slavery, and the thread of that decision was spun into our stitched-up Union by way of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution. In addition to ending human bondage and deciding the right of secession, the war profoundly altered America and its citizens. In the middle 1800s, most men spent their entire lives within a tight radius of their birthplace. But then war came, and young men from Iowa, Minnesota, and Massachusetts enlisted by the tens of thousands in a mad dash to avoid missing what most believed would be a short war. Boys from the rural Iowa prairie found themselves fighting in the swamps of Louisiana; others from big cities marched and died along the Mississippi River; merchants, doctors, clerks, and school teachers, North and South, were blockading Southern ports or manning the massive harbor forts, riding on the roofs of trains through a foreign landscape, or rotting inside prisoner of war camps. Many of those fortunate enough to survive returned home to begin their lives anew. Many others found they were unable to do so, and struck out West to tame new lands and uncover new adventures. All of them, whether they fought for the Union or the Confederacy, began their “second lives” with an entirely different understanding and appreciation for the size and importance of their country, and their own small part in it. The Civil War devastated most of the Southern states, drained away incalculable wealth, and left a bitterness that lingers to this day. More than 600,000 men died and hundreds of thousands more were injured. In the end, the great American experiment endured. What would the modern world look like if America had been cleaved in half in 1865? And so I close as I began. There is a reason why the popularity of the Civil War remains strong, why we linger on its fields, why we fight to preserve what is left, and why we endeavor to teach it to our children. If we forget the defining event in our history, the four long years that make us what we are today, we will do so at the peril of our own existence. Theodore P. Savas El Dorado Hills, California