* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Safeguarding our Soils - UK Government Web Archive

Agroecology wikipedia , lookup

Plant nutrition wikipedia , lookup

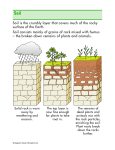

Soil horizon wikipedia , lookup

Human impact on the nitrogen cycle wikipedia , lookup

Soil erosion wikipedia , lookup

Soil respiration wikipedia , lookup

Surface runoff wikipedia , lookup

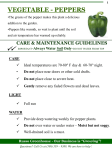

Crop rotation wikipedia , lookup

Soil compaction (agriculture) wikipedia , lookup

Soil food web wikipedia , lookup

Soil salinity control wikipedia , lookup

Terra preta wikipedia , lookup

No-till farming wikipedia , lookup

Soil microbiology wikipedia , lookup

Sustainable agriculture wikipedia , lookup