* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Study of Word Order Variation in German, with Special Reference

Junction Grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Agglutination wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Focus (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Compound (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Untranslatability wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Contraction (grammar) wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Morphology (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sotho parts of speech wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Vietnamese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Icelandic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Basque grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

A STUDY OF WORD ORDER VARIATION IN GERMAN,

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MODIFIER PLACEMENT

January 1994

Ralf Günter Wilhelm Steinberger

Ph.D. Thesis

submitted to the University of Manchester in the Faculty of Technology

Department of Language and Linguistics

University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology

I

This work was carried out under the supervision of Dr. Paul Bennett.

No portion of the work referred to in the thesis has been submitted in support of an

application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or

other institution of learning.

II

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

Abstract

This work discusses word order in written German at sentence level, and suggests how to

deal with word order variation in Machine Translation. It specially refers to modifier

placement, as modifiers are generally neglected in linguistic (word order) description.

The order of phrases in free word order languages is not entirely free, as some variations

can be ungrammatical, and further variations are less natural than others. The intuition of a

German speaker on the adequate word order in a specific context is influenced by at least

eleven factors. In this thesis, these are described independently, and their interaction is

shown. The context plays a major role for the natural word order in a sentence, so that one

can say that sentences are embedded in their context.

After the linguistic description, the methods suggested in literature to model word order

variation in Natural Language Processing are discussed, and a suggestion is made to

overcome the problems linked to word order variation. For analysis, means are provided to

recognise theme, rheme and focus of a given sentence. For synthesis, it is proposed to use a

flexible canonical form which involves over eighty position classes, including places for

the categories theme, rheme and focus. Depending on the analysis of thematic, rhematic

and focused phrases in the source language of the translation, varying German sentences

are generated to guarantee their appropriate embedding in the context. The appendix

contains a list of adverbs including the syntactic features which are necessary for their

automatic treatment.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Paul Bennett for his support,

pointers to relevant literature, his fast reaction, and useful comments.

I would also like to thank my international colleagues and friends who helped me to find

out about tricky aspects of their languages. I am particularly grateful to Tina Burnley,

Archana Hinduja, and Chris Chambers, who put a lot of effort into proof-reading the

thesis. Their comments and suggestions were very helpful. Chris' rules-of-thumb on

modifier placement finally helped me to avoid most errors concerning adverb positioning

in English, on which I failed to have a native speaker's intuition.

Many thanks go also to my former colleagues Dr. Nadia Mesli, Oliver Streiter and Randy

Sharp at the Institute for Applied Information Science (IAI) in Saarbrücken. They

supported me a lot when I implemented my ideas on word order in the Machine

Translation system CAT2, by explaining the formalism as well as the German, English and

French grammars.

And finally, I want to thank Tina Burnley for her excellent cooking and personal support,

especially during the last tiring months.

II

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

Education and Background

1994

• Centre for Computational Linguistics (CCL) at UMIST: TRADE Machine

Translation project (English-Spanish-Italian)

1993

• CCL, UMIST: Conception and Implementation of a German-English dictionary for Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL); planning of

new projects, fund-raising

1991 - 1992

• CCL, UMIST: Machine Translation project EUROTRA (French-English)

• Training in the ET-6 Machine Translation formalism ALEP, Luxembourg

• Summer School for Logic, Linguistics and Information (LLI), Colchester

1991

• Institute for Applied Information Science (IAI), Saarbrücken (FRG):

CAT2 Machine Translation project (German-English)

• LLI Summer School, Saarbrücken

1/1991

• Magister Artium ("with distinction"), München

1986 - 1990

• PANA Schaumstoff GmbH, Geretsried (FRG): Public Relations, sales promotion, production management

1984 - 1985

• Lycée Louis-Le-Grand, Paris: Teacher Assistant (PAD scholarship)

1982 - 1/1991 • Studies of Theoretical, French and Spanish Linguistics at LudwigMaximilians Universität München (1986-1990) and Freie Universität Berlin

(1982-1986)

1981 - 1982

• PANA Werk KG, Wolfratshausen (FRG): Executive Training in the

textiles field

1980

• Abitur, Gymnasium Pullach (FRG), mathematical/scientific orientation

III

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

CONTENTS

1

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROBLEM ........................................................................1

1.1

Scope and Limits of the Thesis ..............................................................................1

1.2

Word Order in a Wider Context.............................................................................6

1.3

Contents................................................................................................................13

1.4.

Problems of German Word Order Description ....................................................16

1.5.

Why Describe Word Order?.................................................................................19

1.5.1

Analysis of German Sentences in NLP ................................................................19

1.5.1.1

Disambiguation of Homonyms ............................................................................20

1.5.1.2

Resolution of PP-Attachment...............................................................................21

1.5.1.3

Recognition of Emphasis .....................................................................................22

1.5.1.4

Contextual Embedding of Sentences ...................................................................23

1.5.1.5

Scope of Degree Modifiers ..................................................................................26

1.5.2

Synthesis of German in NLP................................................................................27

1.5.2.1

Basic Ordering of Constituents ............................................................................30

1.5.2.2

Cumulation of Modifiers......................................................................................30

1.5.2.3

Correct Scope .......................................................................................................31

1.5.2.4

Sentence Embedding ............................................................................................31

1.5.3

Foreign Language Teaching.................................................................................32

2.

COMPLEMENT, MODIFIER, ADVERB AND ADVERB SUBTYPES...............34

2.1.

Modifiers (Angaben) vs. Complements (Ergänzungen) ......................................35

2.2.

Definition and Classification of Adverbs.............................................................39

2.2.1.

Different Definitions of the Adverb.....................................................................40

2.2.2.

Semantic Classification........................................................................................43

2.2.3.

Adverbs and Related Word Classes .....................................................................46

2.2.3.1.

Adverbs and Particles...........................................................................................46

2.2.3.2.

Adverbs vs. Conjunctions and Prepositions.........................................................47

2.2.3.3.

Adverbs vs. Adjectives.........................................................................................49

2.2.4

Conclusion, Final Definition................................................................................55

2.3.

Modifier Types (Angabeklassen).........................................................................57

2.4.

Some Information on the Position of Modifiers ..................................................62

IV

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

2.5.

3.

Some Statistical Facts about Adverbs ..................................................................67

FACTORS WHICH DETERMINE GERMAN WORD ORDER ..........................70

3.1

Theme-Rheme Structure ......................................................................................72

3.1.1

Some Definitions of the Terms Theme and Rheme .............................................72

3.1.2

The Realization of Thematic and Rhematic Elements .........................................74

3.1.3

The Order of Thematic and Rhematic Complements...........................................76

3.1.4

The Separation of Theme and Rheme by Modifiers ............................................80

3.2

Behaghel's "Gesetz der wachsenden Glieder"......................................................81

3.3

Functional Sentence Perspective..........................................................................82

3.3.1

Thematisation and Rhematisation ........................................................................84

3.3.2

Further Means to Express Functional Sentence Perspective ...............................85

3.4.

Verbnähe ..............................................................................................................90

3.4.1.

Which Elements are Semantically Close to the Verb?.........................................93

3.4.1.1.

Arguments ............................................................................................................93

3.4.1.2.

Modifiers ..............................................................................................................95

3.4.2.

Limits of the Verbnähe Principle .........................................................................98

3.5.

The Animacy-First Principle................................................................................99

3.6.

Semantic Roles...................................................................................................101

3.7.

Scope ..................................................................................................................103

3.7.1.

Definitions of Scope...........................................................................................104

3.7.2.

Problems with the Term Scope ..........................................................................105

3.7.3.

The Difference between Scope and Focalisation ...............................................107

3.8.

Rhythm ...............................................................................................................108

3.9.

Natural Gender ...................................................................................................109

3.10.

Grammaticalisation (Habit)................................................................................110

3.11.

Lenerz' "Satzklammerbedingung"......................................................................111

4.

THE INTERACTION OF PREFERENCE RULES, AND SOME

RESTRICTIONS.................................................................................................................113

4.1.

Interaction of the Principles ...............................................................................113

4.2.

Relative Weight of some Principles ...................................................................116

4.3.

Calculation of Acceptability ..............................................................................120

4.4.

Restriction on the Interaction of Preference Rules ............................................123

4.4.1.

Syntactic Subordination .....................................................................................123

V

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

4.4.2.

Possessive Relations...........................................................................................125

4.4.3.

Quantificational Elements..................................................................................126

4.4.4.

The Pragmatic Need of a Sentence Focus..........................................................126

4.5.

Summary ............................................................................................................129

5.

HOW TO DESCRIBE GERMAN FREE WORD ORDER FORMALLY ..........131

5.1.

Acceptability Calculation and LP Rule Disjunction ..........................................131

5.2.

The Relevance of a Canonical Form for German ..............................................133

5.3.

Canonical Forms for German in Literature ........................................................137

5.3.1.

Engel's Canonical Form .....................................................................................138

5.3.2.

Hoberg's Canonical Form...................................................................................139

5.3.3.

New Preliminary Canonical Form .....................................................................141

5.4.

Why Do some Sentences Differ from the Basic Word Order ............................145

5.5.

The Vorfeld Position ..........................................................................................149

5.6.

The Importance of Theme, Rheme and Focus ...................................................154

6.

AIDS FOR COMPUTATIONAL ANALYSIS........................................................159

6.1.

Compulsory Orders ............................................................................................159

6.2.

Recognition of Focus .........................................................................................163

6.3.

Recognition or Theme and Rheme.....................................................................167

6.4.

Some More Details.............................................................................................171

6.4.1.

Permutation of Pragmatic Modifiers ..................................................................171

6.4.2.

Permutation of Modal Modifiers........................................................................172

6.4.3.

Permutation of Pragmatic and Situative/Modal Modifiers ................................173

6.4.4.

Permutation of Situative Modifiers....................................................................174

6.5.

Final Version of the Canonical Form.................................................................177

6.5.1.

Placement of the Theme.....................................................................................177

6.5.2.

Placement of the Rheme.....................................................................................180

6.5.3.

Placement of the Focus ......................................................................................184

6.6.

Preferential PP Attachment ................................................................................189

6.7.

Dictionary Entries for Adverbs ..........................................................................191

6.7.1.

Coding of Adverbs in the Dictionary .................................................................191

6.7.2.

Some Generalizations.........................................................................................201

6.8.

Summary of Chapter 6 .......................................................................................203

VI

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

7.

CONCLUDING REMARKS ....................................................................................205

8.

APPENDIX.................................................................................................................210

8.1.

Angabestellungsklassen (according to Hoberg, 1981: 106-131) .......................210

8.2.

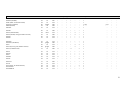

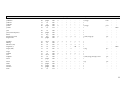

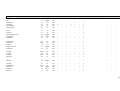

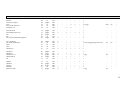

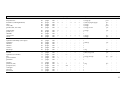

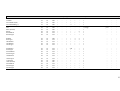

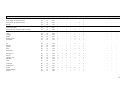

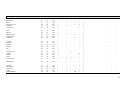

Alphabetical Listing of Modifiers......................................................................214

8.3.

Listing of Modifiers According to Position Classes ..........................................230

8.4.

Canonical Form (Final Version, cf. 6.5.3) .........................................................248

9.

BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................249

VII

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

ABBREVIATIONS

a

ai

8.1)

amod

aneg

apragm, aexist

asit

+/- a

A

Adj

adv

ap

card

Comp

conj

D

+/- d

DIR

Dist

EN

Exp

FSP

G, GEN

Grad

HK87

HO

man

N

Neg

Nom

NP

npp

OF

PO

PP

pragm

Pred

Pre/Post

pron

RS

s

Sit

sit

Angabe (modifier)

index numbers (i) refer to Hoberg's position classes_a1-a44 (cf.

modal modifiers (a42-a44)

negational modifiers (a40)

pragmatic (existimatorial) modifiers (a1 - a18)

situative modifiers (a19-a40)

+/- animate

accusative case

predicate adjective

adverb

adjectival phrase

cardinal numbers

Comparability (can an adverb be compared?)

conjunction

dative case

+/- definite

directional complement

Distance (can a degree modifier be separated from the modified

phrase?)

Ulrich Engel (1988)

expansive complement

functional sentence perspective

genitive case

gradability (can an adverb be modified by a degree modifier?)

Mannheimer Handbuchkorpus 1987 (cf. 6.7)

Ursula Hoberg (1981)

manner modifiers (a43)

nominative case

Negability (can an adverb be negated?)

predicate noun

nominal phrase

NP or PP

Obligatorische-Folge-Regel

prepositional object

prepositional phrase

pragmatic modifiers (a1-a18)

predicative use (can an adverb be used predicatively?)

Does a degree modifier precede or follow modified phrases?

pronominal

Ralf Steinberger

sentence

situative complement

situative modifiers (a19-a40)

VIII

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

SVC

SVO

SOV

TRS

VF

VL

VSO

V2

XP

support verb construction

subject-verb-object word order

subject-object-verb word order

theme-rheme structure

Vorfeld

verb-last, final position of the verb in the clause

verb-subject-object word order

verb-second, second position of the verb in the clause

phrase of whatever category (NP, PP, AP, ...)

SYMBOLS

CAPITALS

-*&

represent semantic roles (AGENT etc)

or indicate (contrastive) stress

A precedes (tends to precede) B

complementary occurrence of A and B

sentence is less acceptable/natural than without "?"

sentence is less acceptable/natural than sentence with "?"

sentence is ungrammatical

ungrammatical; can be considered acceptable if very strongly

stressed (contrast)

unacceptable for semantic reasons

The judgement on the +/- value of a feature is based on occurrences

in the corpus HK87

Although no positive evidence was found in HK87, our intuition is

[...]

that the feature value should be positive (+) (cf. 8.1 and 8.2)

square brackets in quotations indicate omission or addition of text

A<B

A/B

?

??

*

#

!

+/-*

IX

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST 1994)

Meinen Eltern

X

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

1 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROBLEM

Before presenting the contents of this thesis in detail, by describing the chapters one by one

(1.3), we want to point out the scope and the limits of our work (1.1), and set the

investigation in a wider context (1.2). The other sections of chapter 1 are dedicated to the

problems (1.4) and to the benefits of an appropriate word order description (1.5).

1.1 SCOPE AND LIMITS OF THE THESIS

The adequate treatment of word order is still an open problem in linguistics.

(Erbach, 1993: 177)

The goal of this section is to describe both the scope and the limits of this thesis. We also

feel the need to describe the work we carried out earlier as it is the basis for the further

development presented here.

This thesis contains a linguistic word order description of written German at sentence level,

including the variation of constituents, and the limits of their interchangeability.

Furthermore, it makes suggestions on how to use this theoretical knowledge in Natural

Language Processing (NLP) in general, and Machine Translation (MT) in particular. In

Machine Translation, the challenges of language analysis, language synthesis, and languagecontrastive differences are combined. As most other NLP applications have to solve one of

these tasks, they can make use of our suggestions for the treatment of word order in Machine

Translation.

A further use of the data which can be found here concerns foreign language teaching. Word

order in general, and the ordering of modifiers in particular are widely neglected in grammar

books (cf. 2.4). Although the information presented in this work is too detailed for language

learners, it contains many explanations and ordering rules, which can be presented in a

simple way to non-linguists (1.5.3) who intend to learn German as a foreign language.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

2

We limit ourselves to the sentence level, as this is the most difficult part of word order

description. Within nominal (NP) or prepositional phrases (PP), sequences are either

relatively fixed, or they are easy to describe. 1 shows how limited the permutation of noun

arguments is:

1a

1b

1c

1d

1e

1f

1g

*

*

*

*

*

Caesars Verteidigung der Stadt gegen die Angreifer

die Verteidigung der Stadt gegen die Angreifer durch Caesar

die Verteidigung der Stadt durch Caesar gegen die Angreifer

die Verteidigung gegen die Angreifer der Stadt durch Caesar1

die Verteidigung gegen die Angreifer durch Caesar der Stadt

die Verteidigung durch Caesar gegen die Angreifer der Stadt

die Verteidigung durch Caesar der Stadt gegen die Angreifer

Furthermore, the position of determiners, prepositions and adjectival modifiers relative to

nouns does not allow for any variation at all:

2

3

4

* Angreifer die

* die Angreifer gegen

* die Angreifer bösen

Verb participles with the function of noun modifiers are the only elements which allow for

some variation in the sequence of their modifiers (5). Although we did not investigate the

order of these adjuncts, it seems that they follow the same regularities as modifiers at

sentence level. At least the comparison of 5a with 6a and 5f with 6b gives this impression:

5a

5b

5c

5d

5e

5f

das damals dort aus München verfrüht angekommene Flugzeug

das dort damals aus München verfrüht angekommene Flugzeug

das damals aus München verfrüht dort angekommene Flugzeug

das damals dort verfrüht aus München angekommene Flugzeug

das damals verfrüht aus München dort angekommene Flugzeug

* das dort verfrüht aus München damals angekommene Flugzeug

6a

6b

Das Flugzeug kam damals dort aus München verfrüht an.

* Das Flugzeug kam dort verfrüht aus München damals an.

Our research concentrated on the description of declarative clauses, which represent the

major part of most written discourse. It turned out to be the case that main clauses involving

a Vorfeld2 can best be treated as a particular instance of subordinate clauses, which do not

1

The * in 1d refers to 1d as a reformulation of the meaning in 1a.

2

For a brief description of the terms Vorfeld, Mittelfeld and Nachfeld, see section 1.5.2.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

3

have a Vorfeld. Hence our main concern is the Mittelfeld. The treatment of the Vorfeld does

not require a lot of attention (see section 5.5).

Word order regularities in imperative sentences and questions will probably differ slightly

from the order in declarative clauses, in that they can involve a different sentential focus.

The order of the elements which are not affected by the sentential focus, however, should

remain the same.

Although the ordering of verb arguments is dealt with in many parts of the thesis, our

intention was to focus on modifiers. The reason for this is that verb arguments have been

widely discussed, and from different perspectives, whereas the description of modifier

position is generally limited to small subsets. When discussing word order, linguists

generally choose to compare the two frequent groups of temporal and local modifiers (e.g.

Lenerz

1977:

79ff,

Vennemann

1982:

4ff

and

19f,

Gadler

1982:

159f,

Whittemore/Ferrara/Brunner 1990: 29, Oliva 1992b: 11). Others specialise on further

subgroups, such as the distinction between verb modifiers and sentential modifiers

(Heringer/Strecker/Wimmer, 1980: 278). Thurmair (1989) and Weydt (1977) describe toners

(Abtönungspartikeln3), Waltzing (1986) concentrates on existimatorial modifiers, Altmann

(1976 and 1978) on degree modifiers, and Jacobs (1982) on the negational particle.

To our knowledge, Engel (1988, 1973, 1970, and others) and Hoberg (1981) are the only

authors who did not avoid mentioning all the other smaller and bigger modifying subgroups.

Consequently, their work played a major role in our research. The fact that modifiers are less

frequently discussed in linguistics and computational linguistics is reflected in our

bibliography. Many of the books and articles quoted were written more than five or ten years

ago. More recent literature on this neglected field is scarce.4

3

For definitions of the different subclasses see section 2.2.

4

We have used and quoted all relevant articles which appeared in the following journals, reviews and

proceedings (in alphabetical order):

• Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen, 1990 and 1991, Berlin

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

4

Within the description of modifier position, we propose ordering rules, as well as a list of

features, which are necessary to handle modifiers in NLP. We believe that these means are

sufficient to deal with modifiers realised as adverbs, PPs and NPs. On practical grounds,

however, we focus on adverbials realised by single words, such as adverbs, toners, and

others (cf. 2.2). The reason is that one-word modifiers are a closed class which can be listed

exhaustively. This gives the advantage that full dictionary entries, incorporating all details

on their classification and encoding, can be made available.

PPs and NPs, however, are an open class. Its elements have to be analysed and classified

before their handling by the procedure suggested here. We did not suggest solutions for their

analysis, as this is a complex problem which should be investigated independently. We are

convinced, however, that our classification is a first step for their proper analysis, as it

provides the necessary categories and features.

This thesis builds on theoretical and practical work which we have carried out earlier. In our

Magisterarbeit (Steinberger, 1990), we compared word order permutations in hundreds of

example pairs, in order to judge which variations are more natural. The sentences involved

• ACL: Proceedings of the Conference: Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational

Linguistics, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993

• CLAUS: Reports of the Computational Linguistics Department at the University of Saarland, 1990,

1991, 1992, 1993, Saarbrücken

• COLING: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 1990, 1992

• Der Deutschunterricht. Beiträge zu seiner Praxis und wissenschaftlichen Grundlegung, 1990,

1991, 1992, Seelze

• Deutsch als Fremdsprache, 1991 and 1992, München/Berlin

• Deutsche Sprache. Zeitschrift für Theorie, Praxis, Dokumentation, 1990 and 1991, Berlin

• EACL: European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Proceedings of the

Conference, 1991, 1992, 1993

• EUROTRA-D: Working Papers of the Institute of Applied Information Science (IAI), 1986, 1987,

1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992

• Muttersprache, 1991 and 1992, Wiesbaden

• Language. Journal of the Linguistic Society of America, 1990, 1991, 1992, Baltimore

• Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics, 1991 and 1992, Amsterdam

• Linguistic Analysis, 1990 and 1991, Seattle

• Linguistic Inquiry, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992

• Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 1991 and 1992, Dordrecht/Boston/London

• Proceedings of the Third Conference on Applied Language Processing, 1992

• UMIST/CCL-Reports: Reports of the Centre for Computational Linguistics at UMIST, 1981-1993,

Manchester

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

5

all types of verb arguments, as well as elements of all major modifier classes (cf. 2.3). We

also carried out tests on the order of dative and accusative complements, as well as on the

relevance of the animacy and definiteness features for these verb arguments. Both results are

discussed in 4.2 below. On the basis of these results, we described a canonical form, which

we adopt in 5.3.3, and which we develop further in chapter 6.

In the same work, we listed translational difficulties which are not linked to positioning.

These include the complex problem which is the scope of negation, and the fact that some

modifiers are not translated by the same category. In this thesis, we shall assume the

simplest case only, namely the translation of an adverb by an adverb (7). However,

translation is often more complicated.

In the case of transposition (Pelz, 1963: 8ff), adverbs can be translated by another word

class (8). In a special case of transposition, the chassé-croisé, the function of two words is

interchanged (Barth, 1961, 80ff). In 9, for instance, the meaning of the German adverb gern

is represented by the English main verb to like, and the German main verb lesen by the

English subordinate participle reading. The modifier doch in 10 disappears completely in the

target language. In 11, the German adverb causes the use of the continuous form in English.

The difficulty in 12 is that the adverb ganz refers to a PP, whereas its English equivalent

modifies the noun inside the PP5:

5

7

Er kam gestern.

He arrived yesterday.

8

Er wäre beinahe hingefallen.

Il a failli tomber.

9

Ich lese gern.

I like reading.

10

Ich kann doch nichts dafür.

Je n'y

peux rien.

I cannot

do anything about it.

For universally available means to express the meaning of adverbs, see Schachter (1985: 22).

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

11

Er liest gerade.

He is reading.

12

ganz am Ende

at the very end6

6

We shall not discuss these problems any further. Complex translation as in 8 to 12 has to be

treated by different means. For a discussion of such cases see Thurmair (1990), Dorr (1990),

and Lindop/Tsujii (1991). We shall not comment on the scope of negation in this thesis

either. Negation is a complex phenomenon which deserves an independent investigation. For

the treatment of degree modifier scope, see 3.7.

Besides the Magisterarbeit, we shall refer to Steinberger (1992a and 1992b). These papers

present an implementation of German and English modifier treatment within the CAT2

Machine Translation (MT) system. CAT2, a sideline of the European MT system Eurotra, is

a rule-based, unification and constraint-based formalism (Sharp, 1989, 1993). In Steinberger

(1992a), we describe the implementation of German and English word order treatment, as

suggested in chapter 6 of this thesis, with minor differences. In 1992b, we present a way of

recognising and translating degree modifier scope in the same formalism. Degree modifier

treatment is only partially handled in this thesis (3.7 and 6.7). The 1992 papers are thus an

application of the findings presented in this thesis.

1.2 WORD ORDER IN A WIDER CONTEXT

On l'apprend difficilement et est encore plus fascheux à prononcer: de sorte que les

enfants mêmes, qui sont naiz au pays, sont bien grandeletz avant qu'ils puissent

bien former les mots et proférer les paroles. (Claude Duret on the German

language, 17th century, quoted in Scaglione, 1981: 39)7

Some people seem to believe that word order differences between languages are not just

differences in the order of words. It was said that the language of a nation shows how its

people think. One claim is that some languages encourage clear and precise thinking,

6

For an analysis of this special use of the adverb very, see Brugmann (1984).

7

"It is difficult to learn and even worse to pronounce, so that even children who are born in the country are

quite old before they are able to shape and utter the words."

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

7

whereas others are confusing, so that they provide ideal means to evoke emotions, and to

deceive. In 1751, the French philosopher of the Enlightenment, Denis Diderot, affirmed his

conviction that his language was superior to others:

il faut parler français dans la société et dans les écoles de philosophie; et grec, latin, anglais dans les

chaires et sur les théâtres [...] Le français est fait pour instruire, éclairer et convaincre; le grec, le latin,

l'italien, l'anglais, pour persuader, émouvoir et tromper."8

Denis Diderot, as well as his colleague Antoine de Rivarol, claimed that a major reason for

French being so correct, clear and precise is its direct word order, which is due to a lack of

inversion. In 1784, the Prussian Academy even awarded Rivarol a prize for his essay, in

which he used this argument to explain why French was, and deserved to be, the "universal

language of intellectual intercourse" (Scaglione, 1981: 5).

German, on the other hand, is traditionally regarded as a language which is "both unusually

systematic and ultimately illogical, even irrational" with respect to word order (Scaglione,

1981: 3). One peculiarity of German is exactly what, from the French point of view, looks

like inversion, namely the possibility to shift the subject behind the verb, by starting the

sentence with an object or an adverbial. Does the flexibility of word order prevent German

from being clear and precise?

Another equally popular and doubtful myth is one of "German being the philosophical

language par excellence, or at least the ideal language for philosophy" (Scaglione, 1981: 4).

If one believes Martin Heidegger, the lack of direct order, and the illogicality of German do

not particularly prevent German philosophers from having deep insights9:

8

"One should speak French in society and in schools of philosophy; and Greek, Latin and English in

universities and theatres. French is suitable to teach, to enlighten and to convince; Greek, Latin, Italian

and English are suitable to persuade, move and deceive." In: Lettre sur les sourds et muets (1751), quoted

in Scaglione (1981: 5)

9

Martin Heidegger in an interview recorded on September 23, 1966 by the staff of Der Spiegel. Due to the

philosopher's wishes, the interview was only published after his death (Der Spiegel, 30-23, May 31,

1976). Found in Scaglione (1981: 4).

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

8

Ich denke an die besondere innere Verwandtschaft der deutschen Sprache mit der Sprache der Griechen

und deren Denken. Das bestätigen mit heute immer wieder die Franzosen. Wenn sie zu denken

anfangen, sprechen sie Deutsch; sie versichern, sie kämen mit ihrer Sprache nicht durch [...] Weil sie

sehen, daß sie mit ihrer ganzen großen Rationalität nicht mehr durchkommen in der heutigen Welt,

wenn es sich darum handelt, diese in der Herkunft ihres Wesens zu verstehen.

Another more scientific context in which German word order has been discussed is its

comparison with other languages. Vennemann (1982), for instance, contrasts German with

Korean and English. The point of departure for his discussion is that the unmarked order of

elements in the German sentence 13 is similar to the one in Korean (14), but it is nearly a

complete inversion of the English order in 15 (Vennemann, 1982: 10ff):

German:

13

Maria

5

gab

0

gestern

4

Maria

5

yesterday

4

in Seoul

3

einem Freund

2

das Buch.

1

Korean:

14

Seoul_in

3

friend_DAT

2

book_ACC

1

gave.10

0

English:

15

Mary

5

gave

0

the book

1

to a friend

2

in Seoul

3

yesterday.

4

At the sentential level, the Korean word order thus corresponds to the order in German

subordinate clauses, in which the verb is in the final position. Using Greenberg's (1966)

classification, one would say that Korean is an SOV language, a language in which the verb

is in the final position, and in which the subject precedes the object. English, however, is

SVO: the subject precedes the verb, whereas the object follows it. German seems to be SOV

in subordinate clauses, and SVO in main declarative clauses. What does this involve for the

classification of German in Greenberg's typology? Is it SVO, because every sentence has a

10

In Vennemann's paper, the Korean sentence is printed using Korean letters. We are not able to show these

here due to a lack of appropriate printing facilities.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

9

main clause, whereas subordinate clauses can be avoided? Or is it SOV, because the order of

the other elements is very similar to the Korean order?

Whatever the answer is, the complementary distribution of verb positions imposes the view,

that there is an underlying word order. But can we exclude in that case, that German is a

VSO language, as Beckmann (1980) dares to assume? To answer these questions, one has to

consider further facts.

In part of his implicational universals, Greenberg (1966) claims that there is a

correspondence between the position of the verb in the sentence, and other sequences. These

include the position of the preposition relative to the noun, the genitive attribute relative to

its head, the position of adjectives and adverbs relative to the elements they modify, and

many more.

The idea of implicational universals and their correlation was developed further by

Vennemann (1977), who formulated the principle of natural serialisation. This principle

says that languages tend to be consistent in the direction in which elements are specified

(modified or complemented). When modifiers and complements precede their head, the

construction is called pre-specifying (16), when they follow, it is post-specifying (17).

16

complements/modifiers

17

head

head

(e.g. sehr gut)

complements/modifiers

(e.g. Hit der_Woche)

If all specification relations within one language have the same direction, this language is

called consistent. However, many languages, including German, are mixed with respect to

specification direction. The German degree modification shown in 16, for instance, is a prespecifying construction, whereas the genitive attribute in 17 post-specifies its head (the noun

Hit).

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

10

According to Vennemann (1974, 1975), the principle of natural serialisation is one of the

forces which act on languages diachronically. As only consistent languages satisfy the

principle, mixed languages tend to change towards consistency.

If German was an SOV language, Greenberg's fourth universal would suggest that it should

have postpositions, as opposed to prepositions (1966: 79).

Universal 4: With overwhelmingly greater than chance frequency, languages with normal SOV order

are postpositional.

According to Greenberg and Vennemann, adpositions11 are the heads of PPs (pre/postpositional phrases). Prepositional phrases are hence post-specifying constructions, as

the noun phrase complements the preposition. The similarity of German with Korean shown

in 1 suggests that German is pre-specifying at the sentential level. At the PP level, however,

it is post-specifying. Here again, German proves to be a mixed language with respect to

specification direction. If Vennemann's claim is true that languages diachronically tend

towards consistency, where is German going? Is it drifting towards consistent pre- or postspecification?

Scaglione (1981: 29ff) claims that German is developing away from a former basic order

SOV towards the order SVO, and thus towards post-specification. Lehmann (1978b: 49ff) in

principle seems to agree with this view. He maintains that, in earlier times, German, as well

as English, French and Spanish, were SOV languages (see also Fanselow, 1987: 128ff).

While English and the Romance languages have nearly completed their drift towards SVO,

German is still mixed. Lehmann explains the different position of German by the

interference of social forces, which prevented its development towards consistency. The

crucial difference with the neighbouring languages was that, at the beginning of the 16th

century, the sentence-final verb position was introduced artificially for German subordinate

clauses (Lehmann, 1978c: 410ff; see also section 1.5.2).

11

According to Vennemann's terminology, we shall use the term adposition as a superordinate for pre- and

postpositions.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

11

Since that time, two conflicting patterns acted on the German language: the post-specifying

construction SVO in main clauses, and the pre-specifying SOV sequence in subordinate

clauses. According to Lehmann (1978c: 409ff), the new SOV pattern is responsible for the

emergence of several pre-modifying structures, which did not exist before the 16th century.

These include the appearance of several postpositions, the use of preposed relative

constructions, and others.

According to Vennemann (1982: 27f), today's German is closer to being a post-specifying

than a pre-specifying language. It is thus closer to English than it is to Korean, which is a

consistent pre-specifying system. The following graph by Vennemann (1982: 34) visualises

the scale of pre- and post-specification. Consistent post-specifying languages such as Maori

(Vennemann, 1982: 32) belong at the far right of the scale, consistent pre-specifying ones at

the far left.

Korean

German English

+________________________________________________________+_______+______+

consistent

consistent

pre-specipost-specification

fication

A further context in which German word order is frequently mentioned is when discussing

free word order languages. German is opposed to languages with relatively fixed word order

such as English, in that German allows many permutations of constituents at sentence level.

In a sentence with two verb arguments and one sentence modifier, for instance, there can be

six combinatorial possibilities: ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB and CBA. In English,

however, only modifiers have a certain choice of position. When subject and object

interchange, the meaning of the sentence is distorted (cf. 3.3.2):

18a

18b

Der Mann sieht den Tisch.

Den Tisch sieht der Mann.

19a

The man sees the table.

19b * The table sees the man.

The term free word order is rather confusing, and even wrong, as it suggests that all

elements of the sentence can be scrambled and put together in whatever new order.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

12

Obviously, this is not possible in German, as determiners have to precede the noun,

adjectives must be adjacent to the noun they qualify, and the verb position has to be

sentence-initial in yes/no questions, but verb-final in subordinate clauses, just to give a few

examples. For this reason, Schäufele (1991: 365f) suggests the more accurate term free

phrase order for German, and pleads that the term free word order language be used for

languages which also allow the permutation of elements within a phrase, such as Sanskrit,

Latin, Ancient Greek, and Warlpiri. However, as the expression free word order is wellestablished in linguistic literature, we shall keep it.

It is probably less well-known that even the constituents of a sentence cannot be permuted

with each other that easily, and that some restrictions apply. Some constituents must precede

others, and in other cases, one word order variation is more natural. The naturalness of a

sentence is often determined by the context, but sometimes no context makes a sentence

sound natural. Even the replacement of one element by another one, which is closely related

semantically, can make a natural sentence sound odd or even make it ungrammatical.

These last questions, including both the reasons and the limits for word order freedom in

today's German, are the ones we12 shall concentrate on. We mentioned language universals

and diachronic change in order to put our research in a larger context. However, an ultimate

12

It is worth pointing out our use of personal pronouns at the beginning of this thesis: One of the difficulties

of scientific writing is to express oneself in an objective way without producing heavy and artificial

language. Objectivity requires the use of impersonal constructions such as passive voice, nominalisations

and expletives. Readability, on the other hand, calls for an agent who carries out the verbal action. As

psychological tests have shown that active versions of sentences are processed and recalled better

(Macdonald, 1983), I made the conscious decision to use personal pronouns. As there seems to be a strong

convention not to use the first person singular pronoun, we shall stick to the plural.

[...] many scientists and scientific editors now recognise and even promote the use of the active

voice, including the use of first-person pronouns.

Why should we avoid the passive voice? The rhetoric books describe it as "dron[ing] like nothing

under the sun," wordy and unclear, and less direct and less vigorous than the active voice. It may

indeed be all those things, but in addition, psychological research has shown that the active versions

of a sentence are recalled better and verified faster. Scientific texts written in the third person

passive, as "It was concluded that ..." are remembered less well and appreciated less than the same

content written in the active voice. (Macdonald, 1983: 1893)

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

13

answer to the questions regarding language change and language universals is not crucial for

a correct description of today's German language system.

In the next section, we shall present the contents of this thesis.

1.3 CONTENTS

Besides clarifying the scope of this thesis (1.1), and setting the problem of word order

description in a larger frame (1.2), this first chapter intends to present the problems related to

our task (1.4), as well as the different practical benefits which can be reaped from our

results. We shall point out the advantages for language teaching (1.5.3), and for Natural

Language Processing, distinguishing analysis (1.5.1) and synthesis (1.5.2).

Chapter 2 provides the definitions and distinctions we need for a concise word order

description. These are made up of the dichotomous concepts of modifier and complement

(2.1), as well as the definition for the part-of-speech adverb, which is more heterogeneous

than all other word classes. In 2.2, we give a definition which opposes it to related word

classes. As a practical simplification, we shall roughly distinguish three major modifier

types, which will be introduced in 2.3. Section 2.4 summarises the scarce and contradictory

information on the position of modifiers in grammar books. The chapter ends with a few

statistical facts about adverbs (2.5).

Chapter 3 is dedicated to the explanation of the German word ordering mechanism. We list

eleven different factors which explain German native speakers' intuitions on why one word

order variation is better than another. Most of these principles act on verb arguments as well

as modifiers. The strongest factors are linked to theme-rheme structure (3.1), functional

sentence perspective (3.3), verb bonding (3.4), animacy (3.5), and semantic roles (3.6).

Another powerful determinant is the scope of scope-including elements (3.7), which we

discuss again in 4.4.3. Further regularities which have an influence on our word order

preferences are linked to heaviness (3.2), rhythm (3.8), the natural gender of the persons that

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

14

nouns refer to (3.9), hardened grammatical structures (3.10), and finally a regularity which

Lenerz (1977) mentions as "Satzklammerbedingung" (3.11).

Most of these principles are extracted from diverse linguistic literature and grammar books.

The ones concerning natural gender (3.9) and hardening of syntactic structures (3.10) are the

result of our own investigation.

Chapter 4 deals with the question of how these different determinants interact. The most

likely explanation seems to be that all factors act in each sentence. As, depending on the

specific ordering, the factors can require different sequences (4.1), the question arises of how

strong the various principles are (4.2). A model of how to calculate the acceptability of

sentences is presented in 4.3. A problem related to the calculation is, that other factors

restrict the interaction of factors. These constraints are listed in 4.4.

Due to the problems of word order calculation, we suggest further ways of dealing with

word order in chapter 5. The most efficient method proves to be a sophisticated canonical

form (5.2). After discussing two different canonical form versions suggested by Engel

(1988) and Hoberg (1981), we present a new, preliminary canonical form (5.3), which will

be refined in chapter 6. In section 5.4, we compare some sentences with the canonical form

in order to show its appropriateness. We also throw light on the reasons why some sentences

differ from the fixed order which is represented in the canonical form. As the Vorfeld has not

been considered yet, neither in the word order principles nor in the canonical forms, we

discuss its special status in 5.5. Section 5.6 is devoted to the importance of theme, rheme and

focus for the treatment of word order. These categories are essential for the further

suggestions we shall make on word order variation in Natural Language Processing.

Chapter 6 concentrates more specifically on the computational treatment of word order

variation. A major problem for computers is the structural and lexical ambiguity of language.

Reliable grammar rules are crucial for their resolution. Concerning word order, very few

such rules can be formulated in the free word order language German, because some

sequences may be less natural, but they can hardly be excluded. In section 6.1, we present a

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

15

list of the few hard word order rules we have discovered. The discussion of theme, rheme

and focus in 5.6 showed how important these categories are for the translation from one

language into another. In 6.2 and 6.3, we therefore suggest a mechanism to identify the three

categories automatically during the analysis of German.

Section 6.4 contains a number of details which are not mandatory for a successful treatment

of German in Natural Language Processing, but which may help to understand the free word

order phenomenon better. They concern the idiosyncrasies we identified when investigating

the permutations of different modifier subclasses. In the following section (6.5), we

accomplish the preliminary version of the canonical form presented in 5.3.3. Through the

insertion of the flexible categories theme, rheme and focus, we achieve the result that

generated word order differs, depending on the analysis of the source language. A

constituent can have different positions, depending on whether it is thematic, rhematic, or

neutral with respect to these categories.

In 6.6, we present a preference rule for the resolution of some cases of PP attachment. It is

based on our findings concerning which constituent sequences are more natural than others.

Section 6.7 gives an overview of the suggested modifier classes, and the 10 features that are

necessary to treat them in NLP. These are the features used for the classification and coding

of approximately four hundred adverbs listed in the appendix (8.2 and 8.3). In 6.8, we

summarise the procedure presented in chapter 6.

We end the thesis with concluding remarks (chapter 7). These comprise a brief summary of

our findings, an evaluation of the research carried out, as well as suggestions for future

investigations, which could be carried out to complement the research presented here.

The appendix consists of Hoberg's list of modifier classes (8.1), an extended alphabetical list

of adverbs which we encoded using the features presented in 6.7 (8.2), and a third list, which

presents the same modifiers ordered according to position classes (8.3). Appendix 8.3 is

particularly interesting, as it allows the comparison of the feature values of the adverbs

belonging to the same class, and to the same subgroups.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

16

1.4. PROBLEMS OF GERMAN WORD ORDER DESCRIPTION

Daß es in der deutschen Sprache ziemlich viele Variationsmöglichkeiten im

Bereich der Abfolge gibt, bedeutet nicht, daß keine Regeln vorhanden wären. Im

Gegenteil, die Abfolge ist besonders kompliziert geregelt; denn für jede

Folgevariante gibt es spezielle Bedingungen, die sich in speziellen Regeln

niederschlagen. (Engel, 1988: 303)

In this section, we want to present the difficulties related to word order in general, and to

modifier placement in particular, without going into too much detail at present.

One difficulty regarding word order description is that the data is generally fuzzy. There is

no clear cut-off point between grammatical and ungrammatical data, instead there seems to

be a graded borderline with different shades. Furthermore, spoken language differs from

written language, and different concepts which are relevant for the description of word

ordering can easily be mixed up, namely style, meaning, scope, focus, and finally the

semantic versus the syntactic classification of elements.

When dealing with the more specific task of modifier placement, we are confronted with a

further problem, namely that the part-of-speech adverb is one of the most heterogeneous

word classes in German (see also 2.2). This statement also seems to be true for other

languages, as Schachter (1985: 20ff) and Givón (1984: 77ff) confirm in their universaloriented investigations. The differences between the large amount of different adverb classes

make the description of their syntactic behaviour rather difficult.

German word order variation usually changes the relative acceptability of sentences, without

creating either ungrammatical or completely natural utterances. The grammarian

nevertheless has to decide which word order variation is grammatical and which one is not.

As in other domains of linguistic description native speakers differ in their judgements.

Therefore, we have to rely on our own intuition, sometimes backed up by other native

speakers' judgements. To express the grades in the range of acceptability between

grammatical and ungrammatical sentences we shall use the following means:

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

?

??

#

!

*

17

odd, or less acceptable than examples without "?"

less acceptable than "?" (to express grades of acceptability)

ungrammatical; can be considered acceptable if very strongly accentuated (contrast)

unacceptable for semantic reasons

definitely ungrammatical

German grammars only give a partial and rather unsatisfying explanation of where to put

adverbials and what the differences between the positions are (see section 2.4). The general

trend is to make a link between semantic classes and syntactic behaviour. Hoberg's

positional classification of modifiers (1981: 106-131) shows, however, that the semantic and

the syntactic classifications have to be partly dissociated to arrive at an appropriate

description of adverb placement13. This makes the explanation of their syntactic behaviour

even more difficult.

A further problem is the question of what the differences between word order variations of

the same sentence, and subsets of these variations, are. Are they purely stylistical? In this

case it would be interesting to find out what stylistical means. Do they involve a different

meaning? Or does the difference consist of something else, which would then have to be

stated more precisely?

20a

20b

20c

Paul gab gestern der Frau das Buch.

Paul gab der Frau das Buch gestern.

Paul gab das Buch gestern der Frau.

21a

21b !

21c

Paul gab nur der Frau das Buch.

Paul gab der Frau das Buch nur.14

Paul gab das Buch nur der Frau.

The sentences in 21 definitely involve different meanings, as nur is a degree adverb which

changes its scope when moved. But what about 20? According to Engel (1988: 337) all

modifiers have a scope, which means that the movement of gestern in 20 also involves a

change of meaning. What then is this difference and how can we master it in order to be able

13

Greenbaum (1969: 231) makes a similar statement about English.

14

For reasons to be explained in 4.4.4, the only possible place for the sentence focus is the verb gab which

has to be stressed contrastively. 21b is ungrammatical, as it does not make sense to contrast nur geben

since there is nothing to oppose it to. If it was Paul LIEH der Frau das Buch nur, 21b would be perfectly

acceptable, as nur leihen can be imagined in opposition to schenken.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

18

to translate the difference into other languages? This is one of the main questions we shall

focus on.

What are the criteria to decide on the acceptability of sentences? Is 22a more acceptable than

22b?:

22a

Hans traf sie gestern im Kino.

22b # Hans traf gestern SIE im Kino.15

22b is a perfectly acceptable sentence but is contextually much more restricted than 22a

because the personal pronoun sie has to be strongly stressed. It is very easy to mix up

acceptability, focalization and scope, and this increases the difficulty of word order

description.

Spoken and written German certainly differ as speakers often form their ideas while

speaking, whereas most written utterances are more thought-through16. Indeed, utterances

like 23, with the temporal adverb behind the local verb complement, are likely to be heard

but very unlikely to be read:

23

? Ich war im Kino gestern.

We shall concentrate on our own intuition of what contemporary written German is like,

supported by some judgements of other native German speakers. For parts of the work, we

shall also use a corpus of written German to verify our intuition (cf. sections 6.7 and 6.8).

We shall try to differentiate clearly between the different phenomena and to give answers to

the questions asked in this introductory chapter.

15

Throughout this work, we capitalise words or syllables which have to be stressed strongly in order to

make a sentence acceptable. 3b would be ungrammatical if the personal pronoun sie was not stressed

contrastively.

16

Further differences between spoken and written language will be discussed in sections 1.5.1.4 and 3.1.3.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

19

1.5. WHY DESCRIBE WORD ORDER?

There are three main domains to which the precise description of word order in general, and

adverb placement in particular, could be a useful contribution: (a) the general knowledge of

how German and related languages work, (b) foreign language teaching, for which rules-ofthumb can be formulated, and (c) Natural Language Processing. We are mainly interested in

the last of these. Concerning NLP, we shall distinguish between problems arising whilst

analysing a text and whilst generating text. As Machine Translation (MT) is confronted with

both analysis and synthesis of sentences, it is an ideal application for which to discuss the

use of our findings. However, we believe that our work is useful for other NLP applications,

as well.

When talking about Machine Translation, we refer to the rule-based approach as applied in

the MT systems Eurotra, CAT2, METAL, Rosetta and others17. Due to our previous work,

we are most familiar with this approach. Furthermore, it is the only approach which relies on

the precise formulation of linguistic regularities. We do not want to exclude the fact, that our

findings can be of use for other methods, such as the statistical approach. Whether, and how,

our findings could be used for other approaches would have to be subject to a separate

examination.

1.5.1 ANALYSIS OF GERMAN SENTENCES IN NLP

Whilst automatically analysing a given sentence we need to know which word order

variations are ungrammatical, which ones are unlikely or marked, and which ones are likely

to occur. We shall argue in chapter 4 that these three stages are grades of grammaticality.

17

For an introduction to Eurotra, METAL and Rosetta, see Hutchins and Somers (1992: 239ff). For a more

detailed presentation of Eurotra, see Machine Translation Volume 6, Numbers 2 and 3 (1991), and

especially Bech/Maegaard/Nygaard (1991) and Durand et al. (1991). For an introduction to CAT2, see

Mesli (1991: 34ff) and Sharp (1989, 1993). Different approaches to MT, such as the rule-based,

knowledge-based, example-based and statistics-based methods are presented in Steinberger (1993) and

Hutchins/Somers (1992).

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

20

Through the precise description of possible and impossible word order variations we hope to

contribute to the resolution of several problematic domains. These include the

disambiguation of homonyms (1.5.1.1), resolution of prepositional phrase (PP) attachment

(1.5.1.2), recognition of emphasis linked to word order (1.5.1.3), embedding of sentences in

the context (1.5.1.4), and the recognition of degree modifier scope (1.5.1.5). Concerning PP

attachment and degree modifier scope, we offer only partial solutions in this work. However,

as they are related to word order, we shall discuss them briefly for the sake of completeness.

1.5.1.1 DISAMBIGUATION OF HOMONYMS

Disambiguation of homonyms is necessary in both human and machine translation.

In stratificational approaches to Machine Translation, such as Eurotra and CAT2, analysis is

done in several steps. The first level is dedicated to morphological analysis, followed by the

syntactic and the semantic analyses. When a word or a structure is ambiguous, the system

generates two (or more) analysis objects according to the different readings. The general

procedure is to process all readings in parallel, until the ambiguity is resolved. Sometimes

disambiguation is not feasible at all, and often it can be achieved at the semantic level only.

As the parallel translation of several analyses typical for rule-based systems is timeconsuming, it is important to provide tools to solve ambiguity as soon as possible.

The two adverbs ehrlich in 24 and in 25 are word class homonyms, as they are semantically

closely related adverbs which belong to two different sub-classes (for a further explanation

of the term, see 2.3).

Due to their different positional behaviour, they can already be recognised at the syntactic

level, as ehrlich1 in 24 has to precede the negational adverb nicht, whereas ehrlich2 in 25

must follow it:

24

Peter kann ehrlich2 nicht sprechen.

(Honestly, Peter cannot speak)

25

Peter kann nicht ehrlich2 sprechen.

(Peter cannot speak honestly)

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

21

In MT systems of the afore-mentioned type, the first step of the analysis procedure would be

to generate two analysis objects, one with ehrlich1 and one with ehrlich2 (26 and 27). In the

next step, filters of the form: a certain group of elements containing ehrlich2 may not

precede the negational modifier nicht would apply to the two objects. With their help, the

system discovers which readings among 26a, 26b, 27a and 27b are the correct ones. These

homonyms can thus be disambiguated, before entering the phase of semantic analysis, by

checking their position relative to the negational adverb nicht.

26a Peter kann ehrlich1 nicht sprechen.

26b Peter kann ehrlich2 nicht sprechen.

27a Peter kann nicht ehrlich2 sprechen.

27b Peter kann nicht ehrlich1 sprechen.

Our goal is to identify a set of impossible sequences and to formulate them in as general a

way as possible, in order to provide means to disambiguate homonyms, as well as cases of

structural ambiguity.

The real ambiguity in 28, however, cannot be solved without knowledge of the context:

28

Peter kann ehrlich sprechen.

(Honestly, Peter can speak; Peter can speak honestly)

1.5.1.2 RESOLUTION OF PP-ATTACHMENT

Another reason for ambiguity is the ambiguous attachment of prepositional phrases (PP).

The problem with PPs is that very often it is difficult to decide whether they are verb

arguments (prepositional objects), sentence modifiers (adverbials), or attributes or arguments

to nouns, which thus belong to the preceding noun phrase.

We hope that the precise description of word order regularities is a useful contribution to the

identification of the most likely attachment of PPs. The idea is to use our findings on which

constituent sequences are either ungrammatical or unnatural. When one of the readings of

structurally ambiguous sentences is such an unlikely sequence, the other analysis should be

preferred.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

22

An example in which probability can help to choose one reading over the other, is sentence

29. The PP vor der Bank could either be analysed as an adjunct, namely a modifier of the

nominative NP (29a), or as a sentence modifier expressing the location of the whole event

expressed in 29 (29b). We shall see below (e.g. 6.2) that the reading in 29b is unlikely and

should thus be avoided if an alternative analysis, such as 29a, is available. In 30, the strength

of the preference is easier to see, since the attachment of the PP to the pronoun is not

possible (30a). If we want vor der Bank to be a sentence modifier, we tend to use the order

in 30c:

29

Deshalb hat der Mann vor der Bank ihn einfach ignoriert.

29a

Deshalb hat {der Mann vor der Bank} ihn einfach ignoriert.

29b ?? Deshalb hat {der Mann} {vor der Bank} ihn einfach ignoriert.

30a * Deshalb hat {er vor der Bank} ihn einfach ignoriert.

30b ?? Deshalb hat er {vor der Bank} ihn einfach ignoriert.

30c

Deshalb hat er ihn {vor der Bank} einfach ignoriert.

Structural ambiguity as shown in 29 and 30 is not limited to PPs (cp 4.4.1) but it is much

less of a problem for one-word modifiers. As the latter are our main concern, we shall treat

PP attachment resolution only briefly (6.6). We believe, however, that the regularities and

the means discussed in this work can be used to formulate more rules of the same kind.

1.5.1.3 RECOGNITION OF EMPHASIS

The German variation in word order is sometimes used to stress a certain element in the

sentence. In 31a, the personal pronoun sie has to be stressed and is hence the focus of the

sentence, whereas in 31b all five elements of the sentence can be stressed:

31a Paul hat gestern SIE eingeladen.

31b Paul hat sie gestern eingeladen.

It is indeed a regularity that definite personal pronouns must not follow adverbs, unless they

are strongly (contrastively) stressed. This, and other regularities, can be used to detect

focusing due to word order variation in German sentences.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

23

Sentences with contrastive stress, such as 31a, are strongly restricted with respect to the

possible contexts in which they can occur. For instance, 31a is natural when following

context 32 but impossible after context 33:

32

31a'

War Paul gestern bei Marie-Christine oder war sie bei ihm?

Paul hat gestern SIE eingeladen.

33

Wann war Marie-Christine bei Paul?

31a'' * Paul hat gestern SIE eingeladen.

If possible, and depending on the language in which or from which it will be translated, the

differences in meaning and context compatibility should be equally rendered. 31a', for

instance, is equivalent to the Italian sentence 34a in which the stressed pronoun lei is used. A

translation of 31a' (with context 32) by 34b involving the unstressed pronoun la (also called

clitic), and where the sentence focus is on invitata would be wrong:

34a

Ieri, Paul ha invitato LEI.

34b * Ieri, Paul la ha invitata. (as a translation of 31a' in the context 32)

34 and 35 show that rendering the contrastive stress when translating into Italian is essential

to get a sentence which is correct in the context. It is impossible to use the clitic pronoun la

when there is a not-clause (non-clause, in Italian) as this makes the contrast explicit (35a).

Not rendering the Italian stress on lei in 34a into German is less harmful. 36a shows that, if

the context requires it, even the word order in 36a allows stress on sie, even if 36b would be

more natural:

35a * Ieri, Paul la ha invitata, non Maria.

35b

Ieri, Paul ha invitato lei, non Maria.

36a

36b

Paul hat SIE gestern eingeladen, und nicht sie ihn.

Paul hat gestern SIE eingeladen, und nicht sie ihn.

One of the goals of our work is to describe stress due to word order variation appropriately,

and to provide means to recognise, translate and render it in Machine Translation.

Ralf Steinberger – Word Order Variation in German, Modifiers (Ph.D. Thesis, UMIST, 1994)

24

1.5.1.4 CONTEXTUAL EMBEDDING OF SENTENCES

Other word order variations do not lead to obligatory contrastive stress, but rather to a

change of the position of the sentence focus. The differences between 37a, 37b, 37c and 37d

are more subtle than the ones in 31 and 34. Nevertheless, 37a to 37d have different uses and

belong to different contexts:

37a

37b

37c

37d

Paul gab gestern der Frau das Buch.

Paul gab der Frau das Buch gestern.

Paul gab das Buch gestern der Frau.

Der Frau gab Paul das Buch gestern.

...

The main differences between the sentences in 37 concern the theme-rheme structure and

functional sentence perspective (discussed in detail in 3.1 and 3.2). Languages differ in the