* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of beta-blockers wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of proton pump inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of direct thrombin inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of angiotensin receptor blockers wikipedia , lookup

Metalloprotease inhibitor wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of integrase inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of neuraminidase inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of ACE inhibitors wikipedia , lookup

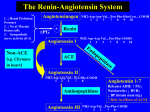

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Properties and Side Effects HARALAMBOS GAVRAS AND IRENE GAVRAS SUMMARY The purpose of this brief review is to separate the characteristic properties and side effects attributable to the pharmacology of the whole class of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors from those attributable to the chemical structure and kinetics of each particular ACE inhibitor. The former would be predictable and probably similar for all agents and, therefore, would be expected to recur with each agent, whereas the latter are likely to be characteristic of individual compounds and may be avoidable by changing to another compound with similar pharmacology but different molecular structure. (Hypertension 11 [Suppl II]: H-37-II-41, 1988) KEY WORDS * angiotensin converting enzyme Inhibition pharmacodynamics • kinetics * class effects * toxic effects Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 and inhibition of the degradation of bradykinin. Accordingly, all lead to suppression of angiotensin II with 1) decrease of blood pressure, which may be normalized in over 50% of an unselected population with mild to moderately severe hypertension when the ACE inhibitor is used as monotherapy and in about 85% when a diuretic is combined with ACE inhibition5-6; 2) vasodilation varying in degree in various tissues (depending on the sensitivity of each organ's vascular tree to angiotensin) and leading to increase in cardiac output and redistribution of regional blood flows in favor of vital organs at the expense of the less-sensitive musculoskeletal tissues7; 3) partial suppression of aldosterone production by the adrenal zona glomerulosa (though stimulation of aldosterone production continues to be exerted by the other two major mechanisms, that is, plasma K + and adrenocorticotropin); 4) increase in circulating levels of plasma renin due to interruption of the negative feedback control exerted normally by angiotensin II on the release of renin; 5) potentiation of the vasodilatory effect of bradykinin (although the physiological significance of this effect has not been fully evaluated); and 6) in the long run, decrease of the activity of the sympathetic nervous system with diminished levels of plasma catecholamines as well as other hormones whose secretion is partly dependent upon the stimulus of angiotensin II (e.g., vasopressin). A NGIOTENSIN converting enzyme (ACE) inhi/ \ bition is the newest approach in the treatment X \ . of hypertension, and in the last few years, it has become increasingly popular as the first choice in the pharmacotherapy of this disease. As with other classes of antihypertensive drugs, such as thiazide diuretics and /3-adrenergic blockers, the pharmacodynamics of this mode of treatment have been most extensively investigated using the first agent of this class that became available, captopril. '•2 After the effectiveness of this treatment was established for hypertension, congestive heart failure, and other indications, the search continued for the production of the second generation of such drugs with similar pharmacological actions but different chemistry, kinetics, and ancillary properties. The aim here was at reducing side effects, improving convenience of administration, etc., while maintaining efficacy. The first drug to become available from this second generation is enalapril, 34 with several others currently being investigated in clinical trials. The purpose of this brief review is to separate the properties, effects, and adverse reactions attributable to the pharmacological action of this class of drugs, that is, the ACE inhibition, from those attributable to the particular chemical structure, kinetics, and ancillary characteristics of each individual agent. Effects of ACE Inhibition All ACE inhibitors share the same mode of action, that is, elimination of the production of angiotensin II As a result, all ACE inhibitors share the same hemodynamic and metabolic effects,8 that is, a blood pressure fall due to decreased peripheral vascular resistance, increased cardiac output, relatively increased renal, cerebral, and coronary blood flow (provided there is no local anatomic obstruction or excessive fall of perfusion pressure), and tendency toward increased elimination of fluid and sodium with retention of potassium by the kidneys (due to partial suppression of aldosterone). Moreover, by changing intrarenal hemo- From the Department of Medicine, Boston City Hospital, and Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts. Supported in part by United States Public Health Service Grant HL 18318 and National Institutes of Health Grant RR-533. Address forreprints:Haralambos Gavras, M.D., Boston University School of Medicine, 80 East Concord Street, Boston, MA 02218. 11-37 11-38 ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG EFPECTS SUPPL II HYPERTENSION, VOL 11, No 3, MARCH 1988 Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 dynamics9 (i.e., reducing to a large extent the tone of both the afferent and the efferent arterioles so that glomerular capillary pressure is usually maintained unchanged despite either fall of systemic arterial pressure or increase in renal blood flow), ACE inhibitors tend to maintain glomerular filtration rate and decrease the preexisting proteinuria associated with parenchymal renal diseases or diabetes mellitus.10 Since their antihypertensive effects are obtained mostly by alteration in the peripheral action of hormones, all ACE inhibitors are free of the common side effects originating from the central nervous system that have been associated with other classes of antihypertensive drugs." For example, drowsiness, fatigue, loss of mental acuity, depression, impotence, vague weakness, and loss of energy are not associated with ACE inhibition. In fact, patients who have lived for long periods of time under the influence of such side effects and who are subsequently relieved of them when switched to an ACE inhibitor sometimes experience an intense feeling of well being on which they comment spontaneously. By the same token, all ACE inhibitors share a number of potential adverse reactions that are inherent in their mechanism of action. Excessive hypotension is always a possibility, especially in patients with malignant hypertension who may have intense renindependent vasoconstriction, in patients with hyponatremia and congestive heart failure, or in patients who are already being treated with diuretics or who may be dehydrated or volume depleted for other reasons.l2 Hypotension is more profound and abrupt with the fastacting captopril, which frequently produces a "triphasic response" characterized by an immediate blood pressure drop occurring within 20 to 30 minutes that is followed by an intermediate rise and a subsequent, more gradual fall over the next few days. The longacting agents like enalapril can produce a gradual but more protracted and persistent hypotension. In either case, the excessive blood pressure response to ACE inhibition can easily be corrected by salt repletion (by i.v. saline on symptomatic cases or by oral salt supplementation in milder cases). Other symptoms attributable to hypotension may also arise in such cases and may become severe or lead to other complications in elderly arteriosclerotic patients with coexisting vascular occlusive disease. Tachycardia, coronary ischemia with angina, cerebral ischemia with syncopal episodes, and decreased renal perfusion ranging from mild azotemia to acute renal failure with transient oliguria or anuria have all been described as adverse reactions after initiation of ACE inhibition; however, all are reversible and should in fact be preventable by cautious assessment of the patient's clinical condition, coexisting diseases, and concurrent treatment, and they are no different from what might be expected from any potent vasodilator. On the other hand, the functional renal insufficiency that has been described in patients with bilateral renal artery stenoses or with stenosis of the renal artery of a solitary kidney appears to be characteristic of ACE inhibition and not simply the result of overall decreasedrenalperfusion. The postulated mechanism for this side effect is the diminished renal blood flow due to anatomic obstruction in combination with the alteration in intrarenal hemodynamics occurring from the elimination of angiotensin's constrictor effect on the renal arterioles, in this case the efferent ones whose tone is necessary for the maintenance of adequate glomerular filtration rate.9'l3 Though clearly functional and totallyreversibleupon discontinuation of the ACE inhibitor, this adverse reaction may become particularly detrimental in patients with kidney transplant who develop stenosis at the site of the arterial anastomosis; it has been described as causing deterioration of the graft's function14'l5 and can pose diagnostic problems if confused with a rejection reaction. Hyperkalemia is another potential side effect of ACE inhibition, attributable to some decrease of aldosterone secretion after elimination of angiotensin II. Normally, the small rise in plasma K+ levels itself can again stimulate the secretion of aldosterone so that a new homeostasis is achieved without reaching hyperkalemic levels. However, in patients with advanced renal insufficiency, in elderly diabetics, in patients treated with nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, in those using salt substitutes, or in those receiving concomitantly potassium-sparing diuretics, a potentially dangerous hyperkalemia can develop.16 Two other peculiar and rare reactions seem to be particular, although ill-defined, side effects of ACE inhibition: angioedema17'18 and a persistent dry cough sometimes accompanied by wheezing.1920 Angioedema has been reported to have an incidence of 0.2% with enalapril and 0.1% with captopril17 and is selflimited and reversible upon discontinuation of the drug. Although triggering of previously dormant asthma has been described with ACE inhibitors,21 in our experience, chronic asthma is not necessarily exacerbated by ACE inhibition. In fact, many hypertensive patients whose asthma had worsened by the use of sympatholytic agents (e.g.,reserpine)reportedsignificant improvement when switched to an ACE inhibitor (H. Gavras and I. Gavras, unpublished observations). However, a chronic dry cough has lately been reported with increasing frequency since it was first recognized as a side effect of ACE inhibitors. Dilutional hyponatremia has been described in patients with congestive heart failure treated with multiple drugs including ACE inhibition22; however, other studies have reported correction of this condition by the use of an ACE inhibitor,23 which may be explained by the suppressing effect of ACE inhibition on vasopressin release. Additional Side Effects of ACE Inhibitors In addition to the side effects attributable to their mechanism of action (i.e., the so-called "class effects," which would be expected to occur more or less with any one drug from the same class), individual ACE inhibitors may display different adverse reactions ACE INfflBITORS/Gavraj and Gavras Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 attributable to their particular chemical structure or kinetics. Captopril contains a modified proline molecule with a mercapto moiety that binds with the zinc atom of the metalloenzyme ACE, thus inactivating it. It is easily absorbed by mouth in the active form, provided it is taken on an empty stomach (because food has been reported to diminish its bioavailability,24 although this may not always be the case). Its onset of action is apparent within 20 to 30 minutes, and its duration of action is probably in the range of 12 hours, usually requiring twice-daily administration. Within the body, it undergoes constant interconversion with its active metabolites, which are excreted in the urine.23 Enalapril and the other second-generation ACE inhibitors that are presently undergoing clinical trials differ from captopril in that they compete with the renin substrate for binding sites of the ACE; therefore, their effect does not depend on the chelating action of a mercapto moiety on the zinc atom of the ACE.3 The lack of a mercapto group should theoretically render these agents free of several side effects. Indeed, because these adverse reactions (listed below) are common to all sulfhydryl-containing drugs, regardless of their particular pharmacological actions (drugs as disparate as heavy metal antagonists and antithyroid agents26), it is speculated that they are attributable to this structure. Enalapril (and several other second-generation ACE inhibitors) is a prodrug, the ethylester of the active diacid compound. It is easily absorbed after oral administration, not hindered by the presence of food, but must be deesterified in the liver, which acts as a reservoir and gradually releases the active diacid. Therefore, it has a delayed onset of action of about 2 hours, a peak at 4 to 12 hours, and usually lasts for 24 hours, thus permitting once-daily administration. The active drug is not further metabolized but is excreted in the urine unchanged. 2728 These different kinetics explain some of the differences in pharmacological properties between the two drugs. The most common adverse effect with any chemical is the possibility of an allergic reaction, with a maculopapular pruritic rash, that may be accompanied by eosinophilia. Both captopril and enalapril have been described to cause such reactions, but their incidence is higher in the former (ranging between 2.5 and 10% in various reports depending on the dosage used12'13) than in the latter (1.2% 17 ). These are usually mild, selflimiting reactions that are more likely to occur in patients receiving higher doses and having underlying conditions that place them at risk, such as renal insufficiency. In addition, captopril has also been reported to cause a wide variety of more severe skin conditions sometimes accompanied by drug fever, including lichenoid eruption,29 a bullous pemphigus-like rash, 3031 rosacea,32 erythroderma with exfoliative dermatitis,33 tongue ulcers, 3433 necrotizing blepharitis,3* and fatal Stevens-Johnson syndrome.37 Bone marrow suppression is another potentially 11-39 serious reaction associated with captopril. Neutropenia with agranulocytosis, 3839 ' 40 thrombocytopenia,41 aplastic anemia,42 and pancytopenia43 have all been encountered with this agent. Although at least three fatal cases have been reported to date, 44 ' 43 ' ** these reactions should be reversible upon discontinuation of the drug, provided they are diagnosed before causing other complications. Again, as with other side effects, the probability of blood reactions rises from 0.02% in otherwise healthy hypertensive patients receiving small doses of the drug to 0.4% in those with serum creatinine over 2 mg/dl to 7.2% in those with coexisting collagen disease concurrently receiving immunosuppressive drugs.47 It should also be pointed out that the incidence of drug-induced leukopenia may be exaggerated because many perfectly healthy subjects, especially from certain racial or ethnic groups, have an idiopathic tendency to wide cyclic changes of white blood cell counts, which, if previously unnoticed, could be mistaken for a drug effect.48 There is one case of reversible neutropenia reported to occur 6 hours after administration of the first 0.6-mg dose of enalapril.49 No other blood reactions have been reported with the usual 5 to 20 daily doses of this drug, even in patients with renal failure. In fact, in a multicenter trial, most of the adverse reactions associated with enalapril had an incidence similar to that observed with a placebo.50 A nephrotic syndrome, presenting with intermittent proteinuria and accompanied by immune-complex neuropathy with pathological changes suggestive of membranous glomerulonephritis or acute interstitial nephritis, is also one of the potential adverse effects of captopril. 5152 This nephrotic reaction should be differentiated from the reversible acute renal failure attributable to ACE inhibition as mentioned earlier, which is characterized by absence of such pathological changes.53'**• 35> x It is also possible that some degree of subclinical glomerulonephritis may exist in the hypertensive population without being necessarily drug related.57 These side effects of captopril, that is, the bone marrow suppression, the nephrotic syndrome, the severe skin reactions, and taste alterations17 ranging from transient or persistent loss of taste to peculiar sulfuric or metallic taste, have been attributed to the molecular structure of the drug and, in particular, to its sulfhydryl moiety. In support of this view is the fact that they appear to be equally common to drugs with different pharmacological properties but similar molecular structure, such as penicillamine and thioureas. 26 ' 50 In fact, there are cases in the literature of patients developing the same reactions to more than one drug from these different classes, for example, captopril and methimazol.59 On the other hand, the majority of patients with previous adverse reactions to captopril could be uneventfully treated with enalapril.17'w> 61 There are also reports of patients with allergic reaction to enalapril (mild skin rash with eosinophilia) treated successfully 11-40 ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUG EFFECTS SUPPL II HYPERTENSION, VOL 11, No 3, MARCH 1988 Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 with captopril,62 indicating that it is clinically important to separate class effects that could be expected to recur with any ACE inhibitor from idiosyncratic reactions to a particular compound. Rare and isolated reports with a questionable causative relationship to captopril include cholestatic jaundice,6364 toxic hepatitis,65 pericarditis and parkinsonism,66 psychotic reactions,67 neuropathy,68 and development of positive antinuclear antibodies69 sometimes accompanying a lupus-like syndrome.70 The possibility of zinc deficiency has also been raised as a result of long-term treatment with captopril.71 Side effects peculiar to enalapril include the possibility of renal glucosuria72 and the potential for diminished bioavailability73 of this agent when administered concurrently with propranolol. It should also be kept in mind that enalapril has been used less extensively, and therefore, there may still be other rare adverse reactions that have not yet been observed or associated with the drug to date. A number of publications have reported adverse effects on the fetus when the mother was treated with captopril during pregnancy. Such effects ranged from increased fetal loss74 to fetal or neonatal renal failure7576 and other abnormalities.77 At this point, it is unclear whether they are specific to captopril or whether they should be attributed to ACE inhibition. However, patency of the ductus arteriosus may well be related to release of prostaglandins enhanced by potentiation of bradykinin. In conclusion, all ACE inhibitors appear to be equally effective in the treatment of hypertension, congestive heart failure, and other indications where ACE inhibition is beneficial. They all share the same small probability of more or less predictable side effects due to their common pharmacological properties, but each one has a number of additional characteristics and potential adverse reactions due to its particular chemistry, kinetics, or other ancillary properties that should be considered separate from the class effects. Several new compounds with different potency, route of absorption and excretion, and different toxicity profiles are currently in earlier stages of clinical development78 and will probably become available in the near future. References 1. Ondctti MA, Rubin B, Cushman DW. Design of specific inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme: new class of orally active antihypertensive agents. Science 1977;196:441-444 2. Gavras H, Brunner HR, Turini GA, et al. Antihypertensive effect of the oral angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitor SQ 14225 in man. N Engl J Med 1978;298:991-995 3. Patchett AA, Haris E, Tristam EW, et al. A new class of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Nature 1980;288: 280-283 4. Gavras H, Biollaz J, Waeber B, Brunner HR, Gavras I, Davies RO. Antihypertensive effect of the new oral angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor 'MK-421'. Lancet 1981;2:543-547 5. Drayer JIM, WebeT MA. Monotherapy of essential hypertension with a converting enzyme inhibitor. Hypertension 1983; 5(suppl in):m-108-m-113 6. Yodfat Y, Fidel J, Bloom DS. Captopril as a replacement for multiple therapy in hypertension: a controlled study. J Hypertens 1985;3(suppl 2):S155-S158 7. Gavras H, Liang C, Brunner HR. Redistribution of regional blood flow after inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme. Circ Res 1978; 43(suppl 0:1-59-1-63 8. Lewis RA, Baker KM, Ayers CR, Weaver BA, Lehman MR. Captopril versus enalapril maleate: a comparison of antihypertensive and hormonal effects. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1985; 7(suppl I):512-515 9. Blytbe WB. Captopril and renal autoregulation. N Engl J Med 1983;308:390-391 10. DeVenuto G, Andreotti C, Mattarei M, Pegoretti G. Longterm captopril therapy at low doses reduces albumin excretion in patients with essential hypertension and no sign of renal impairment. J Hypertens 1985;3(suppl I):S143-S145 11. Vidt DG, Bravo EL, Fouad FM. Medical intelligence: drug therapy. N Engl J Med 1982;306:214-220 12. Frohlich ED, Cooper RA, Lewis EJ. Review of the overall experience of captopril in hypertension. Arch Intern Med 1984;144:1441-1444 13. Hollenberg NK. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition: renal aspect. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1985;7(suppl I):S40S44 14. Farrow PR, Wilkinson R. Reversible renal failure during treatment with captopril. Br Med J 1979;l:1680 15. Collaste P, Haglund K, Lundgren G, Magnusson G, Ostman J. Reversible renal failure during treatment with captopril. Br Med J 1979:2:612-613 16. Ponce SP, Jennings AE, Madias NE, Harrington JT. Druginduced hyperkalcmia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1985;64:357370 17. Davies RO, Irvin JD, Kramsch DK, Walker JF, Moncloa F. Enalapril worldwide experience. Am J Med 1984;77(2A): 23-35 18. Jett GK. Captopril-induced angiodema. Ann Emerg Med 1984:13:489-490 19. Sesoko S, Kaneko Y. Cough associated with the use of captopril [Letter]. Arch Intern Med 1985;145:1524 20. Semple PF, Herd GW. Cough and wheeze caused by inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme [Letter]. N Engl J Med 1986;314: 61 21. Salena BJ. Chronic cough and the use of captopril: unmasking asthma. Arch Intern Med 1986;146:202-203 22. Al-Mufti HI, Arieff Al. Captopril-induced hyponatremia with irreversible neurologic damage. Am J Med 1985;79:769-771 23. Packer M, Medina N, Yushak M. Correction of dilutional hyponatremia in severe chronic heart failure by convertingenzyme inhibition. Ann Intern Med 1984;100:782-789 24. Heel RC, Brogden RN, Speight TM, Avery GS. Drugs 198020:409-452 25. Kripalani KJ, McKinistry DN, Singhvi SM, Willard DA, Vukovich RA, Migdalof BM. Disposition of captopril in normal subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1980^7:636-641 26. Captopril: benefits and risks in severe hypertension [Editorial]. Lancet 1980;2:129-130 27. Gross DM, Sweet CS, Ulm EH, et al. Effect of N-[(S)-1carboxy-3-phenylpropyl]-L-Ala-L-Pro and its ethyl ester (MK421) on angiotensin-converting enzyme in vitro and angiotensin I pressor responses in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1981; 216:552-557 28. Sweet CS, Gross DM, Arbegast PT, et al. Antihypertensive activity of N-[(S)-l-(ethoxycarbonyl)-3-phenylpropyl]-L-AlaL-Pro (MK-421) an orally active converting enzyme inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1981:216:558-566 29. Reinhardt LA, Wilkin JK, Kirkendall WM. Lichenoid eruption produced by captopril. Cutis 1983;31:98-99 30. AurellM, DelinK, HerlitzH, MulecH. Captopril treatment in hypertensive dialysis patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1982; 16:251-256 31. Chriseler A, Waeber B, Brunner HR, Delacr'etaz J. Superficial pemphigus caused by captopril. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1982:112:1483-1486 32. Wilken JK, Kirkendall WM. Pityriasis rosea-like rash from captopril. Arch Dermatol 1982;118:186-187 33. Solinger AM. Exfoliative dermatitis from captopril. Cutis 1982;29:473-474 ACE INfflBITORS/Gavraj and Gavras Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 34. Vlasses PH, Rotmensch HH, Ferguson RK, Sheaffer SL. "Scalded mouth" caused by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Br Med J (Clin Res) 1982^284:1672-1673 35. Nicholls MG, Maslowski AH, Ikram H, Espiner EA. Ulceration of the tongue: a complication of captopril therapy. Ann Intern Med 1981;94:659 36. Wizemann A. Necrotizing blepharitis following captoprilinduced agranulocytosis. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 1983; 182:82-85 37. Pennell DJ, Nunan TO, O'Doherty MJ, Croft DN. Fatal Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a patient on captopril and allopurinol [Letter]. Lancet 1984;1:463 38. Van Brummelen P, Willemeze R, Tan WD, et al. Captoprilassociated agranulocytosis [Letter]. Lancet 1980;l:150 39. Amman FW, Buhler FR, Conen D, et al. Captopril-associated agranulocytosis [Letter]. Lancet 1980; 1:150 40. Staessen J, Fagard R, Lijnen P, et al. Captopril and agranulocytosis. Lancet 1980; 1:926-927 41. Beroniade V. Side-effects of captopril in advanced chronic kidney insufficiency. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 1983; 20:530-537 42. Israeli A, Or R, Leitersdorf E. Captopril-associated transient aplastic anemia. Acta Haematol (Basel) 1985;73:106-107 43. Gavras I, Graff LG, Rose BD, et al. Fatal pancytopenia associated with the use of captopril. Ann Intern Med 1981;94:58-59 44. Iro H, Henschke F, Konig HJ. Reversible panmyelopathy following captopril treatment. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1986; 111:139-141 45. Safar ME. Fatal bone-marrow suppression associated with captopril. Br Med J (Clin Res) 1981; 283:791-792 46. el-Makri, Larabi MS, Kechrid C, Belkahia C, Ben Ayed H. Fatal bone-marrow suppression associated with captopril. Br Med J (Clin Res) 1981;283:277-278 47. Cooper RA. Captopril-associated neutropenia: who is at risk? Arch Intern Med 1983;143:659-660 48. Gavras I, Gavras H. Leukopenia: Idiopathic or drug induced [Letter]. N Engl J Med 1982;306:484 49. Studer A, Vetter W. Reversible leucopenia associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor MK 421 [Letter]. Lancet 1982;1:458 50. Moncloa F, Sromovsky JA, Walker JF, Davies RO. Enalapril in hypertension and congestive heart failure. Overall review of efficacy and safety. Drugs 1985;3O(suppl I):82-89 51. Hoomtje SJ, Weening JJ, The TH, Kallenberg CGM, Donker JM, Hoedemacher PJ. Immune-complex glomerulopathy in patients treated with captopril. Lancet 1980;l:1212-1215 52. Textor SC, Gephardt GN, Bravo EL, et al. Membranous glomerulopathy associated with captopril therapy. Am J Med 1983;74:705-712 53. Fotino S, Spom P. Nonoliguric acute renal failure after captopril therapy. Arch Intern Med 1983;143:1252-1253 54. Mason JC, Hilton PJ. Reversible renal failure due to captopril in a patient with transplant artery stenosis. Case report. Hypertension 1983;5:623-627 55. Coulie P, DePlaen JF, van Ypersele de Strihou C. Captoprilinduced acute reversible renal failure. Nephron 1983;35: 108-111 56. Steinmann TI, Silva P. Acute renal failure, skin rash, and 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. H-41 eosinophilia associated with captopril therapy. Am J Med 1983;75:154-156 Captopril Collaborative Study Group: Does captopril cause renal damage in hypertensive patients? Lancet 1982; 1:988-990 WaeberB,GavrasI,BrunnerHR,GavrasH. Safety and efficacy of chronic therapy with captopril in hypertensive patients: an update. J Clin Pharmacol 1981;21:508-515 Rotmensch HH, Vlasses PH, Ferguson RK. Resolution of captopril-induced rash after substitution of enalapril. Pharmacotherapy 1983;3:131-133 Gavras I, Gavras H. Captopril and enalapril. Ann Intern Med 1983;98:556-557 Smith CD, Smith RD, Kom JH. Hypertensive crisis in systemic sclerosis: treatment with the new oral angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor MK 421 (enalapril) in captopril-intolerant patients. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:826-828 Barnes JN, Davies ES, Gent CB. Rash, eosinophilia, and hyperkalemia associated with enalapril. Lancet 1983^:41—42 Rahmat J, Gelfand RL, Gelfand MC, Winchester JF, Schreiner GE, Zimmerman HJ. Captopril-associated cholestatic jaundice. Ann Intern Med 1985; 102:56-58 Parker WA. Captopril-induced cholestatic jaundice. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1984;18:234-235 Taillan B, Pedinielli FJ, Blanc AP, Jauffret P, Ferrer JC. Toxic hepatitis caused by captopril [Letter]. Therapie 1985;40:263 Sandyk R. Parkinsonism induced by captopril. Clin Neuropharmacol 1985 ;8:197-198 Gillman MA, Sandyk R. Reversal of captopril-induced psychosis with naloxone [Letter]. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:270 Atkinson AB, Brown JJ, Lever AF, et al. Neurological dysfunction in two patients receiving captopril and cimetidine. Lancet 1980;2:36-37 Kallenberg CG, Hoomtje SJ, Smit AJ, et al. Antinuclear and antinative DNA antibodies during captopril treatment. Acta Med Scand 1982;211:297-300 Patri P, Nigro A, Rebora A. Lupus erythematosus-like eruption from captopril. Acta Derm Vemereol (Stockh) 1985; 65:447-448 Smit AJ, Hoomtje SJ, Donker AJ. Zinc deficiency during captopril treatment. Nephron 1983;34:196-197 Cressman MD, Vidt DG, AckerC. Renal glycosuriaandazotemia after enalapril maleate (MK-421) [Letter]. Lancet 1982;2:440 Gomez HJ, Cirillo VJ, Irvin JD. Enalapril: a review of human pharmacology. Drugs 1985; 30(suppl I):13-24 Pipkin FB, Turner SR, Symonds EM. Possible risk with captopril in pregnancy: some animal data [Letter]. Lancet 1980;l:1256 Rothberg Ad, Lorenz R. Can captopril cause fetal and neonatal renal failure? Pediatr Pharmacol (New York) 1984;4:189-192 Guignard JP, Burgener F, Calame A. Persistent anuria in a neonate: a side effect of captopril [Letter]? Int J Pediatr Nephrol 1981;2:133 Boutroy MJ, Vert P, Hurault de Ligny B, Milton A. Captopril administration in pregnancy impaired fetal angiotensin converting enzyme activity and neonatal adaptation. Lancet 1984; 2:935-936 Mackaness GB. The future of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1985;7(suppl I):S30-S34 Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Properties and side effects. H Gavras and I Gavras Hypertension. 1988;11:II37 doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.11.3_Pt_2.II37 Downloaded from http://hyper.ahajournals.org/ by guest on April 30, 2017 Hypertension is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 1988 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0194-911X. Online ISSN: 1524-4563 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://hyper.ahajournals.org/content/11/3_Pt_2/II37 Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Hypertension can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Hypertension is online at: http://hyper.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/