* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download BBC - Athens - Bettany Hughes

Thebes, Greece wikipedia , lookup

Liturgy (ancient Greece) wikipedia , lookup

Acropolis of Athens wikipedia , lookup

Direct democracy wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Prostitution in ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

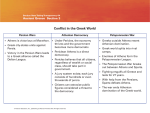

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

Transcript of “Athens: The Truth About Democracy” – Bettany Hughes BBC: Channel Four Productions, 2002 Athens: the Truth About Democracy – Bettany Hughes 0:00-‐5:55 -‐-‐ Introduction: Major Themes in the “Athens: The Truth About Democracy” You’d be hard pushed to find a more familiar image from the ancient world than the Parthenon on top of the Acropolis in Athens. In our heads this has come to represent so many things -‐ democracy, liberty, freedom of speech, the human quest for beauty, the quest for the gods. And it is certainly true that the place that spawned it -‐ 5th century Athens -‐ did generate many of the ingredients that we think is now essential for civilization. This is where demos kratia -‐ democracy -‐ was born. It’s where we get classical lines in architecture, science and philosophy, and drama emerges, and it is where we find the foundations of our own legal system. Of course even the word political comes from the Greek for city state, polis. There is no doubt that 5th century Athens was the most extraordinarily radical place. For the first time in recorded history, the people, hoi polloi, acted as a political agent. So in the Athenian assembly you get pastry sellers next to aristocrats, shoemakers sitting next to generals, and all of them voting how to run their own lives. It’s no surprise, really, that the implements and the example of Athens has echoed down the centuries. But what we mustn’t do is rush to embrace it as a model for all perfect societies. As well as the beautiful art and the very high-‐minded public works we’re more familiar with, the Athenians in the assembly also voted year in and year out to go to war. They enslaved huge numbers of the population of the eastern Mediterranean. In Golden Age Athens Athenian citizens were outnumbered two-‐to-‐one, possibly even three-‐to-‐one by slaves. And I think I would have had a pretty unsatisfying time there. As a woman I would have had civic and religious duties. But I wouldn’t have been allowed to vote in the assembly. I might well have been veiled. I would have been discouraged from speaking out in public. And my name wouldn’t even be spoken. So what we hoped to do in this film was to celebrate both the grit and the glory of Athens. And what we want to do is to show you Athens in all its glorious warts and all humanity. Because this was not a blueprint for society. The Athens of Socrates and Plato and Euripides and Aristotle was a very tumultuous place. This was somewhere where they were dealing with huge changes in the arts and science and philosophy and drama, in religion and politics. And doing so, I have to say, in a remarkably tolerant way. So welcome to the brilliance and brutal place that is Golden Age Athens -‐ the city as you have never seen it before. Two and a half thousand years ago, a Greek city flourished in a quite spectacular way. Out of this place came extraordinary things -‐ philosophy, theater, and a great political idea. The city was Athens, the idea democracy. Democracy triumphed briefly, and then was forgotten. Yet today we venerate it as the cornerstone of western civilization. In Washington, the greatest superpower of the world champions Athenian ideals -‐ liberty, equality and freedom of speech. But are we really the guardians of Greece’s Golden Age? These perfect white columns seem to me to be a great metaphor for what we have done with the classical past. We have taken the world of the ancient Greeks and we’ve whitewashed it. We have turned it into a kind of fantasy. We look back at ancient Athens and we see what we want to see -‐ not what was actually going on. I’m going back to ancient Athens to dig deeper to look at the grit as well as the glory, and to discover the true story of democracy. If you say the name Athens, certain images immediately spring to mind -‐ a beautiful Greek vase, enlightened philosophers, the Parthenon. This is a place that we cherish as the first free and equal Transcribed by Annie Laurie Tuttle – October 2014 78 Transcript of “Athens: The Truth About Democracy” – Bettany Hughes BBC: Channel Four Productions, 2002 society -‐ a good solid basis for our story of democracy. But beneath the Golden Age ideal was a city that constantly voted to go to war, and they ruthlessly carved out an empire to enrich itself. A city which championed freedom of speech, but couldn’t tolerate criticism from within. And now is the perfect time to dissect the idealized picture of Athenian democracy. Because so much has recently been discovered that casts new light on what actually happened here in the Golden Age. … 16:00-‐21:45 -‐-‐ The Role of Slaves and Women in Athenian Society A seismic shift had occurred. And in a world where rule by the many was confined to one city in a thousand, the survival of the infant democracy was in peril. Only 20 years after its foundation, a timely discovery would transform Athens’ fortunes, and turn it into the richest city in Greece. At the dawn of the 5th century BC the ancient city of Athens sat perched on the edge of the civilized world. Democracy might not have survived had it not been for a windfall that made Athens rich. At the bottom tip of the Athenian peninsula lies Laurion, the industrial heart of ancient Athens. Even today the landscape is littered with the spoil of hundreds of abandoned mine shafts. Although off the tourist trail, Laurion has an important story to tell -‐ that the Athenian Golden Age was actually built on silver. People have been mining here since the early Bronze Age because the rock is so rich in mineral deposits. But then in 483 BC the Athenians struck a giant seam of lead, carrying within it precious particles of silver. Overnight democratic Athens was filthy rich. Recent excavations have uncovered an complete settlement of tiny houses and streets. The conditions here are pretty cramped. Actually it’s not that different from other towns and villages of the period. What makes this place different is that -‐ this building has just been identified by archeologists as the remains of a watchtower. The living quarters surrounding the tower were not occupied by citizens, but by slaves. It seems the Athenians wanted to keep their slaves under 24-‐hour surveillance. And it’s no surprise they were jumpy. We are talking massive numbers. As many as one in three of the people who lived in Athens were slaves. The Athenians could be such vigorous democrats because they had someone else to do their dirty work for them. The Athenian citizens felt their freedom all the more keenly as the owners of people who had lost theirs. Paul Cartledge: In ancient Greece, liberty has an inflection, which it doesn’t have in our society, namely there were an awful lot of unfree people -‐ I mean slaves. And in fact not far from where we are standing right now was one of the slave markets in the center of Athens. We mustn’t forget the dark underside of the democratic achievement. Most slaves began their lives as free men and women, but were forced into a life of manual labor when they became prisoners of war. They were bought and sold, separated from their families, sterilized so as not to breed. It wasn’t only slaves. In fact 9/10 of the population were barred from voting. There was an age restriction, and it wasn’t enough to be born in Athens; both your father and your mother had to be born there too. And of the remaining free Athenians, half, like me, were automatically disqualified. Women weren’t just unequal, they were believed to be demonic, possessed by “demones" spirits. They needed to be controlled, visibly restricted. In fact, the first hard evidence of the full-‐face veil comes from Athens. Transcribed by Annie Laurie Tuttle – October 2014 79 Transcript of “Athens: The Truth About Democracy” – Bettany Hughes BBC: Channel Four Productions, 2002 Sue Blundell: Women were not meant to be seen. All evidence from vase painting would suggest that the woman is veiled. She has her cloak draped over her head. Sue Blundell is researching the status of women in Athenian society. Sophocles said silence is the greatest ornament of the woman. The message that is being sent out is that a married woman is the possession of the man. Sue Blundell: Yes, he is the one person in her life for whom she will unveil herself. Simon Goldhill: It wasn’t only Athens; almost every society until the 20th century has been fiercely patriarchal. But there was in that searing mass of experimentation the possibility that something different could have been done. Where do we hear about that? We hear about it as a joke. Aristophanes imagines what would happen if women took over. We hear about it as philosophical thought. So Plato imagines what happens if we got rid of the family and had women as well as men as guardians of his republic. But of course it didn’t happen. Only the free men of Athens could belong to the democratic club, which met together on the Pnyx. At dawn Athenian citizens would come here to sit around on the bare rock and debate in the assembly how it was that they should run their own lives. Transcribed by Annie Laurie Tuttle – October 2014 80