* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 9 - Homework Market

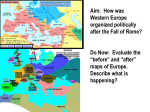

Muslim conquest of the Maghreb wikipedia , lookup

Medieval technology wikipedia , lookup

Post-classical history wikipedia , lookup

Migration Period wikipedia , lookup

European science in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Late Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

History of Christianity during the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Patrimonium Sancti Petri wikipedia , lookup

Early Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

High Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup