* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Determination of the Charge to Mass Ratio of the Electron

Schiehallion experiment wikipedia , lookup

History of electromagnetic theory wikipedia , lookup

Field (physics) wikipedia , lookup

Electric charge wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnet wikipedia , lookup

Superconductivity wikipedia , lookup

Introduction to gauge theory wikipedia , lookup

Aharonov–Bohm effect wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnetism wikipedia , lookup

Electrostatics wikipedia , lookup

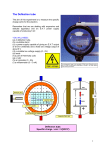

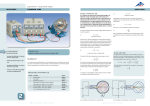

Richard Plews Determination of the Charge to Mass Ratio of the Electron Student: Richard Plews Tutor: A.Aruliah Course 1B40 19th December 2005 Abstract An experiment was conducted to calculate the charge to mass ratio of an electron using J.J. Thomson’s 1897 method by means of opposing forces due to electric and magnetic fields on a beam of electrons from a cathode ray tube. The results proved to be accurate and highly precise, with a final e/m value of 1.724±0.03x1011 Ckg-1. The various disagreements between the theoretical and experimental results do not exceed ± 2% and is attributed largely to voltmeter precision. 1 Richard Plews Introduction There were a number of results gathered over the years by cathode ray tube researchers, J. J. Thomson was a pioneer in this area of research in the 1800s. The e/m ratio that he calculated is important because it is as far as Thomson could get with his cathode ray tubes. Knowledge of the value of 'e' or of 'm' (the charge and mass of an electron respectively) would be needed to get to the other once you knew e/m, which Thomson did know. More information about this subject can be found in "The Discovery of Subatomic Particles" by Steven Weinberg, 1983. Both magnetic and electric fields exert forces on charged particles. The force due to an electric field is given by FE = Ee (1) Where E is the electric field intensity and e is the charge of an electron, while the force due to magnetic field is given by FB = Bev (2) Where B is the magnetic flux density and v is the velocity of the charged particle. Force Electric Field Charge Charge Magnetic field Force Fig 1: Force due to electric field Fig 2: Force due to magnetic field By placing the magnetic and electric fields at right angles, an electron travelling through both fields can continue travelling in an undeterred path by tweaking both fields to have an equal and opposing pair of forces so the resulting force is zero. For nil deflection It is required that Ee = Bev (3) In this experiment, the electron is provided by an electron gun with energy Ee = eVa (4) Where Va is the voltage provided to the gun. Assuming all energy provided is converted to Kinetic energy it can be said that eVa 1 2 mv 2 (5) Rearranging (5) and substituting (4) into this gives e v2 E2 m 2Va 2 B 2Va (6) This means that the e/m ratio can be determined by varying the electric field intensity and magnetic field intensity so that both field forces cancel. Method The main component of the experiment is the e/m Thomson tube, comprised of the elements shown in figure 3. The Helmholtz coils are set parallel at a distance of 6.9cm apart, this is achieved by checking the distance between the coils at the top and sides of the coils to ensure an evenly distributed B-field between them. The electric field is provided by two plates of opposite charge and is contained within an evacuated glass envelope to minimize collisions of the electrons with other particles. The cathode ray gun emits electrons from a filament when a voltage is applied. 2 Richard Plews Helmholtz coils Evacuated glass envelope e - Cathode ray tube Deflection plates Fig. 3: Thomson tube components The apparatus was set up as shown in figure 4. The Electron gun voltage, Va, was set to 3kV when passed through a 1/1000 potential divider. When turned on without any field applied, the beam of electrons is made visible on a luminescent plate parallel to the beam as a green line. The electric field was then turned on with a potential difference of 50V, causing the electrons to accelerate downwards, this force is then eliminated with an equal and opposing force by activating the B-field with the Helmholtz coils. The values of the current required to bring the electron beam deflection back zero were recorded. This process was repeated for varying strengths of the electric field up to 300Vin increments of 25V, and two more repeats were taken to reduce anomalous results. The results given were tabulated and used to create a straight line graph, from which the gradient was used to calculate a value for the e/m ratio using equation (6). 2x Parallel aligned Helmholtz coils Cathode ray tube + Parallel E-field plates 1/1000 Divider Power supply Power supply Power supply Fig. 4: Apparatus diagram 3 Richard Plews Results The average of the three current readings was used to plot the graph. The error bars were created by subtracting the minimum value of the B field current from the maximum value and dividing by two for each voltage. The graph shows the expected linear trend, by increasing the voltage, the current required to result in zero deflection was increased proportionally, however the trend line applied using statistical methods by software does not intercept at 0, which means there must have been a systematic error present as the points are all consistent with the gradient of the trend line. Rearranging equation 6 and substituting in the appropriate formula for B-field strength and E-field strength, it can be shown that using the gradient, M, we can calculate the e/m ratio. e 4.49 10 M m Va 8 E-field p.d/V mean B-field I/A 50 54.00 75 76.00 100 100.33 125 127.33 150 149.67 175 166.67 200 188.33 225 213.67 250 234.33 275 258.67 300 281.00 Figure 5: Results table 2 This gave a final value of 1.724x1011 Ckg-1. The error was then calculated with error propagation methods to give an error of 2.64x109 Ckg-1. 300 Helmholtz Coil Current/mA 250 200 150 100 50 0 0 50 y = 0.9015x + 10.427 100 150 200 Deflector Plate Voltage/V 4 250 300 Richard Plews Conclusion The experimental result lies within 2% of the actual (data book) value of the e/m ratio (1.79x1011 Ckg-1) which is a relatively accurate result and reinforces the theory expectations, however this lies just outside the calculated error range of the results. This is because of the high precision in the results in comparison to the true accuracy. It is possible this has occurred due to poorly calibrated apparatus. The largest contribution to the error was the digital voltmeter display, which could read only to 3 significant figures resulting in an error of ±5V on all voltage readings, which were then taken into account upon calculating the overall error on the e/m ratio. Despite the data book value being outside the range of the calculated errors, it is the product only of having minute error size, otherwise the results can be considered precise and accurate. The way the trend line does not intercept at 0, as the theory suggests it would have done, could have been a cause for concern. The coherence of the results can only suggest this is caused by a systematic fault, either with the way the data was recorded, or with the equipment provided. There were initial problems with recording data caused by the spread of the electron beam, which were later resolved by altering the way ‘nil deflection’ was defined, which may have led to such a result. More repeat sets of data could have been obtained should more time have been available, although it is likely this would only decrease the already near-insignificant error on the e/m ratio more than changing the calculated value itself. A more effective improvement on the method would be to attempt the same experiment with different sets of similar equipment, to detect any possible anomalies in any of the several devices used. References Physics for Scientists and Engineers - Serway Jewett, Brooks Cole, 2004 The Discovery of Subatomic Particles - Steven Weinberg, W.H. Freeman and Company, 1983 5

![NAME: Quiz #5: Phys142 1. [4pts] Find the resulting current through](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/006404813_1-90fcf53f79a7b619eafe061618bfacc1-150x150.png)