* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Part 5 - Islamic Philosophy Online

War against Islam wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Islamism wikipedia , lookup

Islam and Mormonism wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Satanic Verses wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

Imamah (Shia) wikipedia , lookup

Criticism of Twelver Shia Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Judeo-Islamic philosophies (800–1400) wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islam in Egypt wikipedia , lookup

Reception of Islam in Early Modern Europe wikipedia , lookup

Islamic socialism wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

Egypt in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

Usul Fiqh in Ja'fari school wikipedia , lookup

Islam and other religions wikipedia , lookup

Succession to Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup

Part 5. Political Thinkers

Chapter XXXIII

POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EARLY ISLAM

In this chapter we try to elucidate the political thought which laid the foundations of society and State in the early days of Islam, and the changes that crept

into it during the first century and a quarter of the Hijrah.

A

PRINCIPLES OF ISLAMIC POLITY

Muslim society that came into existence with the advent of Islam and the State that it formed on assumption of political power were founded on certain clearcut principles. Prominent among them and relevant to our present discussion were the following: 1. Sovereignty belongs to God, and the Islamic State is in fact a vicegerency, with no right to exercise authority except in subordination to and in accordance

with the Law revealed by God to His Prophet.'

1 Qur'an, iv, 59, 105; v, 44, 45, 47; vii, 3; xii, 40; xxiv, 55; xxxiii, 36.

2. All Muslims have equal rights in the State regardless of race; colour, or speech. No individual, group, class, clan, or people is entitled to any special

privileges, nor can any such distinction determine anyone's position as inferior.2

3. The Shari'ah (i.e., the Law of God enunciated in the Qur'an and the Sunnah, the authentic practice of the Prophet) is the supreme Law and everyone from

the lowest situated person to the Head of the State is to be governed by it.3

4. The government, its authority, and possessions are a trust of God and the Muslims, and ought to be entrusted to the God-fearing, the honest, and the just;

and no one has a right to exploit them in ways not sanctioned by or abhorrent to the Shari'ah.4

5. The Head of the State (call him Caliph, Imam or Amir) should be appointed with the mutual consultation of the Muslims and their concurrence. He

should run the administration and undertake legislative work within the limits prescribed by the Shari'ah in consultation with them.5

' Tradition: "Muslims are brothers to one another. None of them has any preference over another, except on grounds of piety" (Ibn Kathir, Ta/sir al-Qur'an

al-'Azim, Matba'ah Mustafa Muhammad, Egypt, 1937, iv, p. 217).

"0 men, beware, your God is one. An Arab has no preference over a non-Arab, nor a non-Arab over an Arab, nor a white over a black nor a black over a

white, save on grounds of piety" (Aliisi, Ruh al-Ma'ani, Idarat al-Taba'at al-Muniriyyah, Egypt, 1345/1926, xxvi, p. 148; ibn al-Qayyim,Zdd al-Mm dd, Matba'ah

Muhammad 'Ali Sabih, Egypt, 1935, iv, p. 31).

"Whosoever declares that there is no god but God, and faces our gibleh (direction of prayer), and offers prayer as we offer, and eats of the animal we slaughter,

is a Muslim. He has the rights of a Muslim, and the duties of a Muslim" (Bukhari, Kitdb al-Saldh, Ch. xxviii).

"A Muslim's blood is like another Muslim's blood. They are one as distinguished from others; and an ordinary man of them can offer dhimmah (i.e., stand

surety) on their behalf" (Abu DAwild, Kitdb al-Diydt, Ch. xi; Nasa'i, Kitdb al-Qasdmah, Cbs. x-xiv).

"A Muslim is exempt from poll-tax" (Abu Dawiid, Kitab al-Imdrah, Ch. xxxiv).

8 Tradition: "Nations before you were destroyed because they punished those among them of low status according to law, and spared the high-ranking. By

God, who holds my life in His hand, if Fatimah, daughter of Muhammad, had committed this theft I would have chopped off her hand" (Bukhari, Kitab alHudud, Chs. xi, xii).

Says 'Umar, "I myself have seen the Prophet of God allowing people to avenge themselves on him" (Abu Yusuf, Kitdb al-Khardj, al-Matba'at al-Salafiyyah, Egypt,

2nd ed. 1352/1933, p. 116; Mu8nad, abu Daw(Od al-Tayalisi, Tr. No. 55, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad, 1321/1903).

4 Qur'an, iv, 58.

Tradition: "Mind, each one of you is a shepherd, and each one is answerable in respect of his flock. And the chief leader (i.e, the Caliph) is answerable in

respect of his subjects" (Bukhari, Kitdb al-Ahkdm, Ch. i; Kitab al-Imdrah, Ch. v).

5 Qur'an, xiii, 38.

Tradition: "'Ali reports that he asked the Prophet of God (on him be peace), 'What shall we do if we are faced with a problem after you die about which there

is no mention in the Qur'An nor have we heard anything concerning it from your lips ?' He answered, 'Collect those of my people (ummah) that serve God

656

657

A History of Muslim Philosophy

Political Thought in Early Islam

6. The Caliph or the Amir is to be obeyed ungrudgingly in whatever is right and just (ma'ru/), but no one has the right to command obedience in the

service of sin (ma'siah).6

7. The least fitted for responsible positions in general and for the Caliph's position in particular are those that covet and seek them.?

8. The foremost duty of the Caliph and his government is to institute the Islamic order of life, to encourage all that is good, and to suppress all

that is evils

9. It is the right, and also the duty, of every member of the Muslim community to check the occurrence of things that are wrong and abhorrent

to the Islamic State.)

truthfully and place the matter before them for mutual consultation. Let it not be decided by an individual's opinion"' (Aliisi, op. cit., xxv, p. 42).

8 Tradition: "It is incumbent on a Muslim to listen to his Amir and obey, whether he likes it or not, unless he is asked to do wrong; when he is asked to do

wrong, he should neither listen nor obey" (Bukhari, Kitab al-Ahkdm, Ch. iv; Muslim, Kitab at-Tmarah, Ch. viii; abit Dawud, Kitdb al-Jihad, Ch. xcv; Nasu'i, Kitab

atBai'ah, Ch. xxxiii; ibn Majah, Abwab al-Jihad, Ch. xl).

"There is no obedience in sin against God. Obedience is only in the right" (Muslim, Kitab al-Imarah, Ch. viii; abu Dawud, Kitab al-Jihad, Ch. xcv; Nasa'i,

Kitab al-Bai'ah, Ch. xxxiii).

"Do not obey those of your rulers that command you to disregard the order of God" (Ibn Majah, Abn'db al-Jihad, Ch. xl).

I Tradition: "Verily, we do not entrust a post in this government of ours to anyone who seeks or covets it" (Bukhari, Kitab al-Ahkam, Ch. vii).

"The most untrustworthy of you with us is he who comes forward to seek position in the government" (Abu Dawud, Kitab al-Imarah, Ch. ii).

The Prophet of God said to abu Bakr, "0 abu Bakr, the best fitted person for the government is be who does not covet it, not he who jumps at it. He who

knows its responsibility and tries to shun it deserves it moat, not he who proudly advances to collect it for himself. It is for him to whom you could say,

`You most deserve it,' not for him who says of himself, 'I am most deserving"' (Al-Qalgathandi, Subh al-A'a_ha, Dar al-Kutub al-Misriyyah, Cairo, 1910, i, p.

240).

8

Qur'an, xxii, 41.

"Whoever of you sees an evil thing, let him undo it with his hand. If he cannot, let him check it with his tongue. If he cannot do even this, let

him despise it with his heart and wish it otherwise, and this is the lowest degree of faith" (Muslim, Kitab adman, Ch. xx; Tirmidhi, Abwdb at-Fitan, Ch. xii; abu

Dawud, Kitab al-Matahim, Ch. xvii; ibn Majah, Abwdb al-Fitan, Ch. xx).

"Then the undeserving will take their place who will say what they will not do, and will do what they are not asked to do. Therefore, he who strives

against them with his hand is a believer, and he who strives against them with his tongue is a believer, and he who strives against them with his heart is a

believer, and there is no degree of faith below this" (Muslim, Kitab al-Iman, Ch. xx).

"The beet of jihad (endeavour towards God) is to say the right thing in the face of a tyrant" (Abu Dawud, Kitab al-Malahim, Ch. xvii; Tirmidhi, Abwab alFitan, Ch. xii; Nase'i, Kitab al-Bai'ah, Ch. xxxvi; ibn Majah, Abu)db al-Fitan, Ch. xx).

"When people see a tyrant and do not seize his hand, it is not far that God should afflict them with a general ruin" (Abu Dawud, Kitdb al-Maldhim, Ch.

xvii; Tirmidhi, Abuab al-Fitan, Ch. xii).

"Some people are going to be rulers not long after me. He who supports them in

B

1 Tradition:

EARLY CALIPHATE AND ITS CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES

The rule of the early Caliphs that followed the Prophet was founded on the foregoing principles. Each member of the community, brought up under the

guidance and care of the Prophet of God, knew what kind of government answered the demands and reflected the true spirit of Islam. Although the Prophet

had bequeathed no decision regarding the question of his successor, the members of the community were in no doubt that Islam demanded a democratic

solution of the issue. Hence no one laid the foundations of a hereditary government, used force to assume power, or tried to have himself installed as

Caliph. On the contrary, the people, of their own free-will, elected four persons one after another to this august office.

Elective Caliphate.-Abu Bakr was proposed Caliph by 'Umar, and accepted by the inhabitants of Madinah (who for all practical purposes represented the

country) of their free-will and accord, and they swore him allegiance. Abu Bakr, nearing his end, wrote a will in favour of 'Umar: then, collecting the

people in the mosque of Madinah, he addressed them thus: "Do you agree on him whom I am making my successor among you ? God knows I have racked

my brains as much as I could, and I have not proposed a relation of mine to succeed me, but 'Umar, the son of Khattab. Hence listen to him and obey."

Upon this the people responded, "Yes, we shall listen to him and obey.'°)

In the last year of 'Umar's reign a man declared during the pilgrimage that when 'Umar died he would swear allegiance to so and so. Abu Bakr's

installation, he said, had also been so sudden, and succeeded well enough." When 'Umar came to learn of it, he resolved to address the people about it and

"warn them against those who designed to impose themselves upon them." Alluding to it in the first speech he made on reaching Madinah, he gave a

lengthy account of what had transpired at Banu Sa'idah's Meeting House and explained how in the exceptional circumstances which then prevailed he had

suddenly risen to propose abu Bakr's name and offered allegiance to him. "If I had not done so," he said, "and we had dispersed that night without settling

the issue, there was a great danger that people might take a wrong decision overnight; then it would be difficult for us to accept it, and equally difficult to

reject it." "If that was successful," he continued, "let it not be made a precedent. Who among you is there to match with abu Bakr in stature and popularity?

Now, therefore, whoever will swear allegiance to another

their wrong and assists in their tyranny has nothing to do with me, nor have I anything to do with him" (Nasa'i, Kitab al-Bai'ah, Chs. xxxiv, xxxv). 1) AlTabari, Tarik_h at-Umam w-al-Muldk, al-Matba'at al-Istigamah, Cairo,

1939, Vol. II, p. 618.

11 The reference was to the abrupt rising of 'Umar from his place during the meeting at Banu Sa'idah's Meeting House when he proposed abu Bakr's name

as the Prophet's successor and extending his hand to him offered him allegiance. There had been no long deliberation before electing abu Bakr to be Caliph.

658

659

A History of Muslim Philosophy

without consultation with other Muslims, he and the one whose allegiance is sworn, shall both stand to die."12

When 'Umar approached his end, he appointed an Elective Council to decide the issue of succession. Elucidating his principle enunciated above, he

asserted that whoever attempted to impose himself as Amir (ruler) without the consultation of the Muslims deserved to die. He also barred his son from

election" lest the Caliph's office should become a hereditary right, and constituted the Elective Council to comprise those six persons who in his opinion

were the most influential and enjoyed the widest popularity. This Council in the end delegated its power of proposing a person for the Caliph's office to one

of its members, 'Abd al-Rahman bin 'Auf. 'Abd al-Rahman moved among the people to find out as to who commanded their confidence most and left no

stone unturned to ascertain the people's verdict. Even the pilgrim parties returning home after the pilgrimage were consulted. It was after this "plebiscite"

that he concluded that the majority favoured 'Uthman.14

When `Uthman was killed, a few people tried to install 'Ali as Caliph. But he said, "You have no authority to do so. This is a matter for the Consultative

Council (ahl al-aura) and those that fought at Badr (ahl al-Badr). Whomsoever the Consultative Council and the people of Badr will choose Caliph will be

Caliph. Therefore we shall gather and deliberate."10 In al-Tabari's version, 'Ali's words were: "I cannot be elected secretly; it must be with the consultation

of the Muslims."16

When 'Ali lay dying it was asked of him, "Shall we offer allegiance to alIlasan (your son) ?" He replied, "I do not ask or forbid you to do so. You can see

for yourself." 17 When he was addressing his last words to his sons, a person interposed saying, "0 Commander of the Faithful, why do you not nominate

your successor?" His reply was, "I will leave the faithful in the condition in which the Prophet of God left them."13

It is evident from these facts that the early Caliphs and the Companions

12 Bul hari, Kitdb al-Muharibin, Ch. xvi; Ahmad, Musnad, 3rd ed., Dar al-Ma'arif, Egypt, 1949, I, Tr. 391. According to this version, the words are as follows:

"Whoever swears allegiance to an Amir without the consultation of Muslims offers no allegiance, and he who receives allegiance from him receives no

allegiance." In another version the following words are reported: "He who is offered allegiance without consultation, it is not lawful for him to accept it"

(Ibn Ifajar, Fath alBari, al-Matba'at al-Khairiyyah, Cairo, 1325/1907, Vol. II, p. 125).

13 Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 292; ibn al-Athir, Idarat al-Taba'at alMuniriyyah, Egypt. 1356/1937, Vol. III, pp. 34, 35.

14 Al-Tabari, op. cit.. Vol. III, pp. 295-96; ibn al-Atir, Vol. III, pp. 36-37. Also ibn Qutaibah, al-Imamah w-al-Siyasah, Matba'at al-Futuh, Egypt. 1331/1912,

Vol. I, p. 23.

Ibn Qutaibah, op. cit., p. 41.

Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 450.

17 Ibid., Vol. IV, p. 112; al-Mas'udi, Muraj al-Dhahab, al-Matba'at al-Bahiyyah, Egypt, 1346/1927, Vol. II,p.42.

16 Al-Mas'udi, op. cit., p. 42.

'0

16

Political Thought in Early Islam

of the Prophet regarded the Caliph's office as an elective one, to be filled

with mutual consultation and consent of the Muslim community. They did not regard hereditary succession or one acquired by force of arms as anything

valid.

Government by Consultation.-The first four Caliphs did not perform their administrative or legislative functions without consulting "the wise" (ahl atra'y, lit., those that are able to give advice) of the community. They also realized that those consulted had the right to give their candid opinion without

fear. 'Umar expressed the official policy in this regard in his inaugural speech before a Consultative Council in this way: "I have called you for nothing

but that you may share with me the burden of the trust that has been reposed in me of managing your affairs. I am but one of you, and today you are the

people that bear witness to truth. Whoever of you wishes to differ with me is free to do so, and whoever wishes to agree is free to do that. I will not

compel you to follow my desires."19

The Exchequer-a Trust.-The treasury (Bait al-Mal) was to them a trust from God and the public. They did not consider it permissible to receive into it or

expend from it a sum which the Law did not authorize. To use it for the personal ends of the rulers was, according to them, simply unlawful. 'Umar in a

speech remarked: "Nothing is lawful for me in this trust of God save a pair of clothes for the summer and a pair of clothes for the winter, and subsistence

enough for an average man of the Quraish for my family. And after that I am just one of the Muslims."20

In another speech he said: "I do not regard anything correct in respect of this trust of yours but three things: that it should be taken by right, that it should

be expended by right, and that it should be withheld from wrong. My position regarding this property of yours is the same as that of an orphan's guardian

with the orphan's property. So long as I am not needy I will take nothing from it. When I am needy I shall take as it befits one to take from an orphan's

property under his care."21

When 'Ali was at war with Mu'awiyah he was exhorted by some to use the treasury to win adherents against him who was drawing large numbers to his

side by giving sumptuous rewards and gifts. But 'Ali declined to take that counsel saying, "Do you want me to win success by unfair means ?"22 His brother

'Aqil wished to be helped from the Bait al-Mal, but he refused him, saying, "Do you wish your brother to give you the money of the people and take his

way to hell? "23

Ideal of Government.-What their ideal of government was, what they thought of themselves, of their status and duties as rulers, and what policy

19 Abu Yusuf, op. cit., p. 25.

20

Ibis Kathir, al-Bidayah w-al-Nihayah, Matba'at al-Sa'adah, Egypt, Vol. VII, p. 134.

21

Abu Yusuf, op. cit., p. 117.

22 Ibn abi al-Hadid, Lharh Nahj al-Baldabah, Dar al-Kutub al-'Arabiyyah,

Egypt, 1329/1911, Vol. I, p. 182. 23 Ibn Qutaibah, op. cit., p. 71.

660

661

A History of Muslim Philosophy

they followed-questions like these and others were answered in the various

speeches addressed by them from the Caliph's pulpit. Abu Bakr, in the first

speech he made following the oath of allegiance to him in the Mosque of

Madinah, said, "I have been made a ruler over you though I am not the best

of you. Help me if I go right, correct me if I go wrong. Truth is faithfulness

and falsehood is treachery. The weak one among you will be strong with me

till I have got him his due, if God so wills; and the strong one among you

will be weak with me till I have made him pay what he owes, if God so wills.

Beware, when a nation gives up its endeavours in the way of God, He makes

no exception but brings it low, and when it allows evil to prevail in it, un

doubtedly He makes it miserable. Obey me as long as I obey God and the

Prophet; if I do not obey them, you owe me no obedience." 21

And 'Umar in a speech said, "No ruler holds so high a position as to have

the right to command obedience in defiance of God. 0 people, you have rights on me which I shall relate before you, and you may take me to task over

them. I owe you this that I do not receive anything from your revenues or the fai' (lands or possessions that accrue to Muslims in consequence of their

collective dominance, not as booty in war) given to us by God except in accordance with the Law, and that nothing that accrues to us in these ways

should go from the treasury but rightfully."26

Al-Tabari quotes 'Umar giving instructions to all persons whom he sent

out as governors in this wise: "I have appointed you governor over the followers of Mullammad (on whom be peace) not to make you masters of their

persons and properties but to enable you to lead them to establish prayer, dispose of their affairs with justice, and dispense their rights among them with

equity." 88 'Umar once declared in public: "I have not sent my governors that they may whip you and snatch your property, but that they may instruct you in

your faith and the way of your Prophet. If there be any who has been treated otherwise, let him bring me his complaint. By God, I will see that his wrong is

avenged." Upon this 'Am bin 'As, Governor of Egypt, stood up and asked, "What, when a man is appointed ruler and he chastizes someone, will you take

revenge on him?" 'Umar replied, "Yes, by God, I will take revenge on him. I

have seen the Prophet of God himself allowing people to take revenge on him."On another occasion 'Umar collected all his governors at the annual pilgrimage and announced in a general congregation of people that if there was a person who had a charge of injustice against anyone of them, he should

come

forward to make his complaint. One person rose from the multitude and complained that he had been undeservedly given a hundred stripes by 'Amr bin 'As.

4

M: Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 450; ibn Hiahhham, al-Shat al-Nabawlyyah,

Matba'ah Muslafa al-Babi, Egypt, 1936, Vol. IV, p. 311.

!5 Abu Yusuf, op. cit., p. 117.

26 Al-Tabari, op. cit., p. 273.

!° Abu Yusuf, op. cit., p. 115; Musnad, abu Dawud al-Tayalisi, Tr. No. 55; ibn al -At_hir, Vol. III, p. 30; al-Tabari, op. est., Vol. III, p. 273.

Political Thought in Early Islam

'Umar asked him to come forward and square the account with him. 'Amr bin 'As protested, beseeching 'Umar not to expose his governors to this humilia-

tion, but 'Umar reiterated that he had seen the Prophet of God himself allowing men to avenge themselves upon him, and asked the aggrieved man to step

forward and take his revenge. 'Amr bin 'As saved his skin only by appeasing the man with a pair of crowns for each stripe that was to fall on his back.26

Rule of Law.-The "Right-going" Caliphs did not regard themselves above law. On the other hand, they declared that they stood at par with any other citizen

(Muslim or non-Muslim) in this respect. They appointed judges, but once a person was appointed a judge he was free to pronounce judgment against them

as against anybody else. Once 'Umar and Ubayy bin Ka'b differed in a matter, and the dispute was referred to Zaid bin Thabit for decision. The parties

appeared before Zaid. Zaid rose and offered 'Umar his own seat, but 'Umar sat by Ubayy. Then Ubayy preferred his claim which 'Umar denied. According

to the procedure, Zaid should have asked 'Umar to swear an oath but Zaid hesitated in asking for it. 'Umar himself swore an oath, and at the conclusion of

the session remarked that Zaid was unfit to be a judge so long as 'Umar and an ordinary man did not stand equal in his eyes."

The same happened between 'Ali and a Christian whom he saw selling his ('All's) lost coat-of-snail in the market of Kiifah. He did not seize it from the

fellow with a ruler's might, but brought the case before the magistrate concerned; and as he could not produce adequate evidence to support his claim, the

decision of the court went against him. 30 Ibn Khallikan reports that once 'Ali and a non-Muslim citizen (dhimmi) appeared as parties in a case before the

Judge Shuraih. The judge rose to greet 'Ali who was Head of the State at that time. Seeing this 'Ali said to Shuraih, "This is your first injustice." S

Absence of Bias.-Another distinctive feature of the early days of Islam was that everybody received an equal and fair treatment exactly in accordance with

the principles and the spirit of Islam, the society of those days being free from all kinds of tribal, racial, or parochial prejudices. As the Prophet of God

passed away, the tribal jealousies of the Arabs rose again like a heldup storm. Tribal prejudice formed the main impulse behind the claims to prophethood

and large-scale apostasy that immediately followed the Prophet's demise. One of Musailimah's followers said, "I know Musailimah is a false prophet. But a

false one of the (tribe of) Rabi'ah is better than the true one of the (tribe of) Mudar."32 An elder of the Banu 'hatafan, similarly taking sides with another

false prophet, Tulaihah, said, "By God, it is easier for me to follow a prophet of one of our allied tribes than one from the tribe of Qurais_h."33

28 Abu Yasuf, op. cit., p. 116.

22 Baihaqi, al-Sunan al-Kubra, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad, lst ed., 1355/1936, Vol. I. p. 136.

33 Ibid.

31

Wa/ayat al-A'yan, Maktabat al-Nahdat al-Misriyyah,Cairo, 1948, Vol. II, p.168. 32 Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 508.

1

33 Ibid.,

p. 487.

662

663

A History of Muslim Philosophy

Political Thought in Early Islam

But when the people saw that abu Bakr (r. 11-13/632-634), and in his wake 'Umar (r. 13-23/634-644), dispensed exemplary, even-handed justice not only

among the various Arab tribes but even among the non-Arabs and non-Muslims, and that they did not show any favour or even preference to their own

nearest kith and kin, the old biases were instantly repressed and Muslims were once more inspired with that cosmopolitan outlook which Islam sought to

inculcate in them. Abu Bakr and 'Umar's attitude in this respect was most exemplary.

Towards the end of his reign 'Umar became apprehensive lest these tribal currents which, despite the revolutionizing influence of Islam, had not succumbed altogether, should shoot up again and cause disruption after him. So, on one occasion talking to 'Abd Allah bin 'Abbas regarding his possible successors, he said about 'Uthman, "If I propose him my successor I fear he would suffer the sons of abu Mu'ait (the Umayyads) to ride on the necks of people,

and they will practise sin among them. God knows, if I do so, 'Uthman will do this; and if 'Uthman does this, they will surely commit sins, and people will

rise against 'Uthman and make short work of him."34

This apprehension clung to him even in the hour of his death. Summoning 'Ali, 'Uthman, and Sa'd bin abi Waggas to his bedside, he said to each one, "If

you succeed me as Caliph, do not allow the members of your clans to ride the necks of people."35 Besides that, among the instructions which he left for the

Elective Council of Six, on which devolved the task of electing the new Caliph, was this that the new incumbent was to be asked to give a pledge that he

would not show discrimination in favour of his own clan.38 Unluckily, however, the third Caliph, 'Uthman (r. 23-35/644-656) failed to keep up the standard

set by his predecessors and inclined towards favouring the Umayyads. This was regarded by him as "good office to the kindred." Thus, he used to say,

"'Umar deprived his kin for the sake of God, but I provide for my kin for His sake."37 The result was what 'Umar had apprehended. There was a rising

against him, which led to his murder and rekindled the sleeping embers of tribal bias into a fire that consumed the whole edifice of the "Right-going"

Caliphate.

After the death of 'Uthman, 'Ali (r. 35-41/656-661) tried to recapture the standard set by abu Bakr and 'Umar. He had no bias in him and showed himself

remarkably free from it. Mu'awiyah's father, abu Sufyan, had taken note of it when he had tried to excite this passion in him on abu Bakr's accession. He

had asked him, "How could a man of the humblest family in Quraish become Caliph? If you prepare to rise, I will undertake to fill this valley with

horsemen and soldiers." But 'Ali had coldly retorted that this spoke for his enmity to Islam and the Muslims, and so far as he was concerned, he regarded

Ibn 'Abd al-Barr, al-Isti ab, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad, 2nd ed., Vol. 11, p. 467. 35 Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 264.

Ibn Qutaibah, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 25. 87 Al-Tabari, op. cit., Vol. III, p. 291.

abu Bakr truly fit for that office.38 Therefore when he came to be Caliph he treated the Arabs and non-Arabs, gentlemen and poor-born, Has_himites and

others, all alike. No distinction was made between them, and none received preference over the others undeservedly. 39

34

a4

C

THEOLOGICAL DIFFERENCES AND SCHISMS

The period of the "Right-going" Caliphate, described above, was a luminous tower towards which the learned and the pious of all succeeding ages have

been looking back as symbolic of the religious, moral, political, and social orders of Islam par excellence. Abu Hanifah, employed at elucidating the Islamic

ideals in the fields of politics and law, as we shall presently see, also reverted to it as the ideal epoch to take instance from. We have, therefore, devoted a

good deal of space to it, that the reader may be able to comprehend his work in the true background.

But before attending to his work we have also to take a brief view of the reactionary movement that had set in towards the end of the "Right-going"

Caliphate and reached its height by the time abu Ilanifah appeared on the scene. As his efforts were mainly devoted to countering this reaction, it is

necessary to take stock of it and the problems that sprang from it, to be able to grasp the true significance of his work.

Differences among Muslims had sprung up during the last years of 'Uthman's reign, leading to his murder, but they had not yet assumed theological or

philosophical shape. When after his death in the reign of 'Ali these differences raged more furiously than ever and led to a civil war resulting in bloodshed,

as in the battle of the Camel (36/656), the battle of Siffin (37/657), the "arbitration" (38/659), and the battle of Nahrawan (38/659), questions like "Who is in the

right in these battles, and how?", "Who is in the wrong and why ?", "If some regard both sides as wrong, what is their ground for holding this?", naturally

cropped up and demanded to be answered. These questions led to the framing of certain opinions and justifications that were essentially political in the

beginning, but as each group sought to strengthen its position by calling theological support in aid of its particular stand, these political factions gradually

changed into religious groups. Then, the bloodshed which accompanied these factional feuds in the beginning and continued during the rules of the

Umayyads and the 'Abbasids, did not allow these differences to remain only theological; they went on growing ever more acute and menacing till they

threatened the national unity of the Muslims. Every house was a place of controversy, every controversy suggesting ever-new political, theological, and

philosophical offshoots. Every new question that cropped up

38

Ibid., Vol. II, p. 449; ibn 'Abd al-Barr, op. cit., p. 689.

39

Ibn abi al- 1ladid, op. cit., pp. 180, 182.

664

665

A History of Muslim Philosophy

gave birth to a number of new sects which subdivided themselves into further sects over minute internal differences. These sects were not content to fill

themselves with bias against one another; their polemics often ended up in quarrels and riots. K5fah, the capital of 'Iraq, where abu Hanifah was born, was

the chief centre of these quarrels. The battles of the Camel, Siffin, and Nahrawan had all been fought in 'Iraq. The heart-rending murder of Husain (61/680),

the Prophet's grandson, had also taken place here. It was the birthplace of most of these sects and the field where both the Umayyads and the 'Abbasids

used the maximum of coercion to repress their opponents. The time of abu Hanifah's birth (80/699) and growth coincided with these factional hostilities at

their height.

The large number of sub-sects that grew out of these factions had their oots in four main sects: the i'ah, the Khawarij, the Murji'ah, and the

r Mu'tazilah. We shall give here a brief account of the doctrines of each of them before proceeding further.

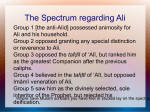

The Shi'ah.-They were the supporters of 'Ali and called themselves the Sbi'ahs (party) of 'Ali. Later (the word 'Ali was dropped and) they began to be

called only Shi'ahs.

Although a section of the people of Banu Has_him and a few others regarded 'Ali as the best suited person to have succeeded the Prophet, and some

regarded him superior to the other Companions, particularly to 'Uthman, and others considered him to be more entitled for the Caliphate because of his

relationship with the Prophet, yet up to the time of 'Uthman these opinions had not assumed the form of a creed or religious belief. Nor were the people

who held these opinions hostile to the first three Caliphs. On the other hand, they acknowledged and supported their succession. As a separate party with

clear-cut views on these matters, they emerged in 'All's reign during the battles of the Camel, Siffin, and Nahrawan. Later, the cold-blooded slaughter of

Husain rallied them, fired them with a new wrath, and shaped their views into a separate creed. The indignation provoked among the general Muslim

populace by the vile deeds of the Umayyads and the sympathy excited in their breasts for the descendants of 'Ali on account of their constant persecution in

both the Umayyad and the 'Abbasid regimes, lent extraordinary support to Shiite propaganda. They had their stronghold at Kiifah. Their beliefs were as

follows: 1. The Imam's office (particular Shiite term for Caliph's office) is not a

public office the institution of which may have been left to the choice

of the public (ummah). The Imam is a pillar of the faith and the founda

tionstone of Islam. Therefore, it is one of the main duties of the

Prophet to institute somebody as Imam instead of leaving the matter to

the discretion of the community 90

40 Ibn

Khaldiin, Mugaddima1, Matba'ah Mustafa Muhammad, Egypt, p. 196; al-Shahrastani, Kitab al-Milal w-al-Nihal, London, Vol. I, pp. 108, 109.

Political Thought in Early Islam

2. The Imam is impeccable, i.e., free from all sins, great or small. He is immune from error. Everything that he says or does is inviolate.41

3. The Prophet had conferred the Imamate on 'Ali and nominated him as his successor. Thus 'Ali was the first Imam by ordinance.42

4. As the appointment of the Imam is not left to be made by public choice, every new Imam will be appointed by an ordinance from his predecessor. 91

5. All the Shi'ah sects are also agreed that the Imam's office is the exclusive right of the descendants of 'A11. 49

Beyond this general agreement, however, the various S_hi'ah sects differed among themselves. The moderate among them held that 'Ali was the best

created man. He who fought or bore malice against him was an enemy of God to be raised among infidels and hypocrites, and destined to live in hell. "If

'Ali had refused to recognize their Caliphate as legitimate and expressed displeasure with them, abu Bakr, 'Umar, and 'Ut_bman who preceded him as

Caliphs would also have deserved that doom; but as 'Ali recognized them and swore them allegiance and offered prayers behind them, we cannot take

exception to what he took as right. We do not differentiate between 'Ali and

the Prophet except that the latter was endowed with prophethood; for the rest 'Ali was worthy of the same esteem as the Prophet. "45

The fanatical among them held that the Caliphs before 'Ali were usurpers and those who elected them were ill-guided and unjust, as they belied the

Prophet's will and deprived the rightful Caliph of his due. Some went further

and pronounced anathema against the first three Caliphs and declared them and their electors excommunicated.

The softest of them were the Zaidiyyah, followers of Zaid (d. 122/740) son of 'Ali, son of Husain. They regarded'Ali as superior to others, but allowed

the choice of those who were inferior to him. Moreover, they held that the Prophet's decision in favour of 'Ali was not unequivocal; hence they accepted the

Caliphate of abu Bakr and 'Umar. All the same, they preferred the choice of an able person from among the descendants of Fatimah (the Prophet's

daughter) as Imam, provided he claimed that position and challenged the title of "the kings" to it 4° Abu Hanifah was closely connected with Zaid, as we

shall see in the course of this chapter, although he did not contribute to the Zaidite doctrine.

The Khawdrij.-In direct opposition to the Shi'ahs the Khawarij stood at the other extreme. They suddenly grouped together during the battle of Siffin.

Ibn Khaldfin, op. cit., p. 196; al.&hahrastani, op. cit., p. 109.

op. cit., p. 108; ibn Khaldfin, op. cit., pp. 196-97.

44 Ibn Khaldfin, op. cit... p. 197; al-As_h'ari, Magatat al-Isl¢miyyin, Maktabat

al-Nahdat al-Mi¢riyyah, Cairo, 1st ed., p. 87; al-Ehahrastani, op. cit., p. 109. 94 Al-IZhahrastAni, op. cit., p. 108.

4° Ibn abi al-Iladid, op. cit., Vol. IV, p. 520.

41 Al-As_h'ari, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 129; ibn Khaldfin, op. cit., pp. 197-98; al. dhahrastani, op. cit., pp. 115-17.

666

41

12 Al-Shahrastani.

667

A History of Muslim Philosophy

Till then they were among the staunch supporters of 'Ali, but when, during that engagement, he consented to submit

his quarrel with Mu'awiyah to the decision of two arbiters, they abandoned him asserting that he had turned infidel

by accepting to submit to the verdict of human arbiters instead of God. After that they drifted farther and farther

away and being fanatical hot-heads, who believed in waging war against those who differed from them and against

"unjust government" wherever one was found, they indulged in war and bloodshed for a long time till their power

was finally crushed under the 'Abbasid rule. They, too, were most influential in 'Iraq, their camps being mainly

centred in al-Bata'ih between KSfah and Basrah. Their beliefs briefly were as follows:

1. They acknowledged abu Bakr and 'Umar as Rightful Caliphs but 'Ut_hman, in their opinion, had, towards the

end of his reign, erred from the path of justice and right conduct and hence deserved to be deposed or killed. 'Ali

also committed, according to them, a major sin when he accepted the "arbitration" of "one besides God." The two

arbiters ('Amr bin 'As and abu Miisa alAsh'ari), their choosers ('Ali and Mu'awiyah), and all those who agreed to

arbitration were sinners. All those who participated in the battle of the Camel including Talbah, Zubair, and

'A'is_hah, the Prophet's wife, had been guilty of grievous sin.

2. Sin, with the Khawarij, was synonymous with infidelity. Anyone who committed a major sin (and did not repent

and revert) was placed outside the pale of Islam. All the personages mentioned above were declared infidels.

Anathema was pronounced against them, and they were considered fit to be censured. The Muslims in general were

pronounced infidels, first, because they were not free from sins, and, secondly, because they not only regarded these

persons as Muslims but also acknowledged them as reliable guides, and deduced and verified the law from traditions

reported by them.

3. The Caliph, according to them, should be elected by the free vote of the Muslims.

4. The Caliph need not be a member of the tribe of Quraish. Whomsoever they elected from amongst the honest

Muslims would be a rightful Caliph.

5. A Caliph was to be obeyed faithfully as long as he acted rightly and justly; but if he forsook the path of right

and justice, he was to be fought against and deposed or assassinated.

6. The Qur'an was recognized as the authoritative source of Law but their views on Hadith (the Prophet's

Tradition) and ijrrna' (the agreement of Muslims in respect of a rule of Law) were different from those of the

majority.

A large group of them, which called itself al-Najdiyyah, did not believe in the very need of a State. The Muslims,

they said, should of themselves abide by the right. However, if they needed a Caliph to direct their affairs, there was

no harm in choosing one.

Their major section, the Azarigah, dubbed all Muslims, excepting themselves, polytheists. The Khawarij,

according to them, could not go for prayer

Political Thought in Early Islam

in response to any but a Karijite's call. They could neither take the meat of an animal slaughtered by non-Kharijites,

nor marry among them, nor could a Kharijite and a non-Kharijite inherit each other's possessions. They considered

war on all other Muslims to be a religious duty and sanctioned the killing of their women and children and the

looting of their property. They declared those of their own sect as infidels if they shirked this duty. They allowed

treachery with their opponents and were so malicious that a non-Muslim would find himself safer in their midst

than an average Muslim.

The most tolerant of them were the Ibadiyyah who refrained from declaring the other Muslims as polytheists

although they put them outside +he pale of Islam and described them as unbelievers. Their evidence, the Ibadiyyah

said, was to be accepted, marriages with them and inheritance to and from them allowed. Their territory too was not

to be called dar al-kujr (the land of the infidels) or dar al-barb (the land of the people at war) but ddr al-tauhid (the

land of the people of one God) although they excepted the centres of their government from it. They disallowed

secret assaults on other Muslims, although open warfare with them was not repugnant 47

The Murji'ah.-The conflicting principles of the Shi'ahs and the Khawarij were responsible for the birth of another

sect, called the Murji'ah.

Apart from the people who had flung themselves violently in support of 'Ali or against him during his wars, there

was a section which had remained neutral either wisely avoiding to indulge in civil war which they deemed a curse

or being unable to decide which side fought for the truth. These people quite realized that it was a veritable curse for

Muslims to indulge in bloodshed and mutual slaughter, but they were not prepared to blaspheme any of the belligerents, and left it to God to decide the affair between them. He alone would tell, on the Day of Judgment, which of

them struggled for the right cause and which for the wrong. So far their ideas agreed with those of the Muslims in

general, but when the Shi'ahs and the Khawarij raised questions as to what was faith and what constituted infidelity

ushering in an era of doctrinal wrangling and polemical contests, this neutral group evolved some theological

doctrines in support of its position. Briefly stated they were as follows:

1. Faith comprises belief in God and the Prophet. One's action does not form an integral part of one's faith.

Hence a believer will remain a believer though he should eschew his duties or commit grave sins.

2. Salvation depends on faith alone. No sin will hurt one who has faith. It is enough for a man's redemption that

he should abstain from polytheism and die as a monotheist 4s

Some of the Murji'ah, taking a step further, affirmed that short of

49 'Abd al-Qahir Bagh-dadi, al-Farq baia al-Firaq, Matba'at al-Ma'arif, Egypt,

pp. 55, 61, 63, 64, 67, 68, 82, 83, 99, 313, 315; al-Shahrastani, op. cit., pp. 87, 90-92,

100; al-Ash'ari, op. cit., pp. 156-57, 159, 189, 190; al-Mas'ndi, op. cit., p. 191.

48 Al- Shahrastani, op. cit., pp. 103, 104; al-As_h'ari, op. cit., pp. 198, 201.

668

669

A History of Muslim Philosophy

Political Thought in Early Islam

49

polytheism all sins, even the worst, would be forgiven. A few, taking a further leap in that direction, asserted that if a man cherished faith in his heart but

worshipped idols or adopted Jewish or Christian doctrines and spoke heresy in the Islamic State where he lived under no fear, he would yet be quite fast

grounded in faith, remain a friend of God, and deserve to go to

paradise .50

Another view closely comparable with the one mentioned above was that if one's duty to uphold the right and stem the wrong (amr bi al-ma'rul and nahi

'an al-munkar) required one to bear arms, it was a "trial" to be avoided. It was quite right to check others on wrong conduct, but to speak loud against the

tyranny of government was not allowed.5' Al-Jassa was very bitter on these things and asserted that they strengthen the hands of tyrants and greatly

demoralized the Muslims' power of resistance against the

forces of evil and wickedness.

The Mu'tazilah.-This tumultuous period was responsible for the birth of

yet another sect known to Islamic history as "the Seceders." Although it did not owe its origin, like the former three, to purely political factors, like them it

contributed its share of opinions to the political issues of the day and entered the arena of theological disputes that raged in the Islamic world at that time,

particularly in Iraq. The leaders of this group, Wasil bin 'Ata (80-131/699-748) and 'Amr bin 'Ubaid (d. 145/763) were both contemporaries of abu Hanifah,

and Basrah was the centre of their religious contests in the beginning.

Their political views were briefly these:

1. The appointment of an Imam (or, in other words, the institution of the State) was a religious urgency. Some Mu'tazilites, however, opined that the

Imam's was a superfluous office. No Imam was needed if the community

followed the right path."

2. The choice of the Imam, according to them, rested with the community,

and only the community's choice validated his appointment ca Some of them held that the choice should be unanimous, and in the event of differences and

dissensions the appointment should be suspended and held in abeyance. 64

3. The community could choose any morally qualified and efficient person as Imam. The condition of his being a Qurais_hite, an Arab, or a non-Arab

was irrelevant" Some of them actually preferred the appointment of a non-Arab;

Al-fihahrastani, op. cit., p. 104.

Ibn ljazm, al-Fa81 fi al Milal w-al-Nihal, al-Matba'at al-Adabiyyah, Egypt, 1317/1899, Vol. IV, p. 204.

51 Al-Jaese4, Ahkam al-Qur'an, al-Matba'at al-Bahiyyah, Egypt, 1347/1928, Vol. II, p. 40.

67 Al-Mas'udi, op. cit., p. 191. 58 Ibid.

64 Al-fihahrastani, op. cit., p. 51. 65 Al-Mas'udi, op. cit., p. 191.

it was better still if he could be a freed slave, for he would have fewer devotees, and it would be easy to depose him if he turned out to be a tyrant s6 They

would rather have a government which was weak and easy to depose than one that was bad but strong and firmly established.

4. According to them, the Friday or other congregational prayers could not be held behind an unrighteous Imam s7

5. Amr bi al-ma'ru/ w-al-nahi 'an al-munkar (enjoining what is right and forbidding what is wrong) was among their fundamental principles. It was a

duty with them to rise in arms against an unjust government provided they had the power to do so and hoped to raise a successful coup.65 Thus it was that

they rose in arms against the Umayyad Caliph Walid bin Yazid (r. 125126/743-744) and tried to replace him by Yazid bin Walid who espoused their

doctrine of secession."

6. On the question of the inter-relation of sin and infidelity, over which the Khawarij and Murji'ah were at loggerheads, their verdict was compromising.

A sinful Muslim was neither a believer nor an unbeliever, but one in the middling state.so

In addition to these principles, the Mu'tazilah pronounced bold verdicts upon the differences among the Prophet's Companions and upon the issue of

Caliphate. Wasil bin 'Ata declared that one of the two opponents in the battles of Camel and Siffin was surely a "transgressor" although it was hard to say

who. It was for this reason that he said that if 'Ali, Tall}ah, and Zubair came before him to give evidence on a vegetable knot, he would not accept it of

them since there was a possibility that they had been guilty of transgression. 'Amr bin 'Ubaid pronounced both sides as "transgressors." 61

They also attacked 'Ut-hman vigorously and some of them did not spare even 'Umar." Besides this, many of them practically rejected Hadittthh (the

Prophet's Tradition) and ijma' (the consensus of opinion) as authoritative sources of Islamic Law. 83

The Major Section.-In the midst of these violent, wrangling groups the large majority of Muslims went along subscribing to the orthodox principles and

doctrines, accredited as authoritative since the days of the "Right-guided" Caliphs, principles and precepts which the Prophet's Companions and their

successors and Muslims in general had commonly regarded as Islamic. However, nobody, from the time of the inception of the schism down to the days of

abu Hanifah, had vindicated the stand of the majority in these matters of

69

s0

Al-3 ahrastam, op. cit., p. 63.

Al-As_h'ari, op. cit., p. 124. 11 Ibid., p. 125.

" Al-Mas'iidi, op. cit., pp. 190,193; al-Suyati, Tarikh al-Khula/a', Government

Press, Lahore, 1870, p. 255.

so Al-Baghhd5di, op. cit., pp. 94-95.

61 Ibid., pp. 100, 101; al-fih_ahrastani, op. cit., p. 34.

62 Al-Bagh_dadi, op. cit., pp. 133-34; al-Shahrastani, op. cit., p. 40. 63 Al-Bag-hdadi, op. cit., 138-39.

670

56

51

671

A History of Muslim Philosophy

violent divergences, and presented it methodically in a compact, doctrinal form, although learned men, traditionists, and scholars of repute and integrity

had from time to time been bringing one or another aspect of it to light by word of mouth or action, or embodying it in their behaviour or sacred pronouncements as opportunity afforded itself.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Qur'an and Commantaries.-Qur'an; ibn Kathir, Ta/sir al-Qur'an al-'Azim, Matba'ah Mustafa Muhammad, Egypt, 1937; Alasi, Ruh at-Ma'ani, Idarat alTaba'at al-Muniriyyah, Egypt, 1345 H.; al-JaE6as al-Hanafi, Ahkarn al-Qur'an, al-Matba ut al-Bshiyyah, Egypt, 1347 H.

2. Judith and Commentaries.-Al-Bukhari; abu Dawod; abu Dawud al-Tayalisi, al-Mu8nad, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad, 1321 H.; Muslim; al-Nasa'i; ibn

Majah; al-Tirmidhi; Ahmad bin Hanbal, al-Musnad, Dar al-Ma'arif. Egypt, 3rd ed., 1947; ibid., Matba'at al-Maimaniyyah, Egypt, 1306 H.; ibn Hajar, Fath alBari, alMatba'at a1- cjiairiyyah, Cairo, 1325 H.; al-Baihaqi, al-Sunan al-Kubra, DairatulMaarif, Hyderabad, 1st ed., 1355 H.

3. Al-Figh.-Abu Yiisuf, Kitab al-Kharaj, al-Matba'at al-Salafiyyah, Egypt, 2nd ed., 1352 H.

4. Al-Kaldm.-Al-Shahrastani, Kitab al-Milal w-al-Nihal, London; al-Ash'ari, Magalat al-Islamiyyin, Maktabat al-Nahdat al-Misriyyah, Cairo, 1st ed.; 'Abd

al-Qahir al-Bagh_dadi, al-Farq bain al-Firaq, Matba'at al-Ma'arif, Egypt; ibn Hazm, al-Fagl fi al-Milal w-al-Nihal, al-Matba'at al-Adablyyah, Egypt, 1317 H.

5. Biographies.-Ibn al-Qayyim, Zad al-Ma'ad, Matba'ah Muhammad 'Ali Sabih, Egypt, 1935; ibn His_ham, al-Sirat al-Nabawiyyah, Matba'ah Mustafa alBabi, Egypt, 1936; ibn Khallikan, Wa/ayat al-A'yan, Maktabat al-Nahdat alMisriyyah, Cairo, 1948; ibn 'Abd al-Barr, al-Isti'ab, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad,

2nd ed.

6. History.-Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Umam w-al-Mvluk, aI-Matba'at al-Istiqamah, Cairo, 1939; ihn al-At_hir, al-Kamil ft al-Tarik_h, Idarat al-Taba'at alMuniriyyah, Egypt, 1356 H.; ibn Qutaibah, al-Imamah w-al-Siyasah, Matba'at al-Futnh, Egypt, 1331 H.; ' Uyan al-Akhbar, Matba'ah Dar al-Kutub, Egypt, 1928,

1st ed.; al.Mas'fidi, Muruj al-Dhahab wa Ma'adin al-Jawahir, al-Matba'at al-Bahiyyah, Egypt, 1346 H.; ibn Kathir, al-Bidayah w-al-Nihayah, Matba'at al-Sa'adah,

Egypt; ibn Khaldan, al-Muqaddimah, Matba'ah Mustafa Muhammad, Egypt; al-Suyiiti, Tarikh alKulaja', Government Press, Lahore, 1870; Hush al-Muhadarah fl

Akhbar Misr w-al-Qahirah, al-Matba'at al-Sharifiyyah, Egypt; Ahmad Amin, Duha al-Islam, Matba'ah Lajnah al-Talif w-al.Tarjamah, Egypt, 4th ed., 1946; alKhatib, Tarikh Baghdad, Matba'at al-Sa'adah, Egypt, 1931.

7. Literature.-Al-Qalgas_handi, Subh al-A'sha fi Sand'at al-Ins_ha', Dar al-Kutub al-Misriyyah, Cairo, 1910; ibn abi al- I,ladid, Sharp Nahj al-Balaghah, Dar

al-Kutub al-'Arabiyyah, Egypt, 1329 H.; ibn 'Abd Rabbihi, al-'Iqd al-Farid, Lajnah alTalif w-al-Tarjamah, Cairo, 1940; abu al-Faraj al-Asbahani, Kitab alAg_hani, al-Matba'at al-Misriyyah, Bdlaq, Egypt, 1285 H.; al-Rag_hib al-Asbahbni, Muhadarat al-Udaba', Matba'at al-Hilal, Egypt, 1902; al-Murtada, alAmali, Matba'at alSa'adah, Egypt, 1st ed., 1907.

8. Miscel aneous.-Tas_h Kubrazadah, Mijtah al-Sa'adah, Dairatul-Maarif, Hyderabad, 1st ed., 1329 H.