* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Eight Challenges Faced by GPs Caring for Patients After Acute Coronary Syndrome

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Saturated fat and cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

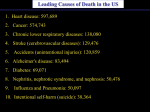

Cardiovascular disease wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

History of invasive and interventional cardiology wikipedia , lookup

Drug-eluting stent wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup