* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download -click here for handouts (full page)

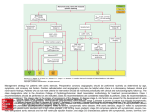

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Marfan syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Infective endocarditis wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Lutembacher's syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

PRESSURE OVERLOAD LESIONS • Pressure overload to the Ventricle – AS, PS – HCM, Subaortic AS and Infundibular PS – Supra-aortic and Supra-pulmonic PS • Pressure Overload to the Atria – Mitral Stenosis – Tricuspid Stenosis AORTIC STENOSIS VOLUME OVERLOAD LESIONS • Ventricular Volume Overload – AR and PR • Atrial Volume Overload – Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation MITRAL REGURGITATION PRESSURE OVERLOAD LESIONS-VENTRICULAR • Ventricular hypertrophy in response to AS or PS • Dilatation may occur if hypertrophy is inadequate, apoptosis occurs, or fibrous tissue replacement • Atrial dilatation occurs in response to ventricular hypertrophy with systemic or pulmonary venous hypertension often related to reduced relaxation and compliance from ventricular hypertrophy and increases interstitial myocardial fibrous tissue PRESSURE OVERLOAD LESIONS-VENTRICULAR • Symptoms are of LVOT or RVOT obstruction • AS: DOE, angina, syncope on effort • PS: fatigue, angina, syncope on effort PRESSURE OVERLOAD LESIONS-VENTRICULAR • LVOT or RVOT murmur – SEM: AS-2nd RICS to carotid PS-3rd LICS – PMI heave and S4 VOLUME OVERLOAD LESIONS • Both AR and MR affect the LV as a volume overload • AR is a direct volume overload and MR is due to excessive atrial filling • The LV dilates and hypertrophies eccentrically; atrial dilatation ensues with LA hypertension*, and pulmonary venous congestion* • Right heart dilatation then ensues* • *The rate at which these effects occur on the atrium and right heart depend on whether the volume overload is directly to the atria or not. VOLUME OVERLOAD LESIONS • • • • • Displaced PMI S3 Diastolic filling murmur across mitral valve Regurgitant murmur Right heart findings: – JVD – Enlarged and pulsatile liver – edema VOLUME OVERLOAD LESIONS • • • • Dyspnea on exertion Palpitations Angina Syncope-Arrthymogenic Patient presents with 3/6 systolic murmur difficult to determine if holosystolic or not at the LLSB. • Which of the following diagnostic tests is most appropriate and will provide you and with the most useful information? – – – – CT angiography Cardiac catheterization and angiography Comprehensive cardiac MR imaging Transthoracic echocardiography Diagnostic Testing • Echocardiography: (repeat 6 months to 1 year, 1-2 years, or >3 years for mild, moderate or severe disease) – – – – Severity of the valve lesion-Doppler Presence of pulmonary hypertension Co-existent lesions Alterations of chamber size and function • Exercise testing: functional capacity, changes in gradients and degree of regurgitation • B Natiuretic peptide-prognostic in AR, AS, and MR • Cardiac Catheterization-hemodynamics if echo data questionable and coronary arteriography ETIOLOGY OF VALVAR AS EXCISED AS VALVE VALVULAR AS • Calcific or senile degenerative-shares feature with CAD and other vascular disease – Active process – Inflammatory – Calcium deposition • Bicuspid-manifests in 50’s • Rheumatic-with mitral disease • Congenital-younger BICUSPID AV PHYSIOLOGIC RESPONSE TO AS • LV response to AS – LVH to normalize wall stress Stress=R/WT*P • Generate sufficient force to overcome valve narrowing (occurs at 50% of valve area ie 1.5 cm2) – Concentric hypertrophy: Radius/Wall Thickness is low; increased interstitial fibrosis-leading to dyspnea – Late: LV dilatation and dysfunction (> in men) • Left atrial enlargement • Right side normal unless RHD or late 76 year old male • Patient with known systolic murmur though to be AS and determined as moderate to severe by echo 1 year ago presents with angina. How would you evaluate the angina? – – – – Stress echo Exercise Nuclear stress testing PET imaging with adenosine stress Coronary Angiography HISTORY • Angina: Thick muscle difficult to perfuse especially with increased fibrosis and CAD also present in >50% of patients; need coronary angiography • Syncope on effort: can not increase cardiac output due to orifice obstruction and peripheral vasodilatation from high LV wall stress • DOE: LV dysfunction, dilatation and reduced relaxation and elevated LV filling pressures • 5 yr survival: 50%, 30%, 20% • Survival is not impaired if no symptoms but symptoms related to severity 81 year old female • Patient with history of mild AS 10 years ago presents with increasing dyspnea. She has been found to have peak velocity across the aortic valve of 4.2 m/s • Why does she have dyspnea? – Coronary ischemia due to LVH and inability to perfuse the subendocardium – LV dysfunction – Impaired relaxation and increased myocardial LV stiffness (reduced LV chamber compliance) – Increased fraility with age HISTORY • Angina: Thick muscle difficult to perfuse especially with increased fibrosis and CAD also present in >50% of patients; need coronary angiography • Syncope on effort: can not increase cardiac output due to orifice obstruction and peripheral vasodilatation from high LV wall stress • DOE: LV dysfunction, dilatation and reduced relaxation and reduced LV compliance and elevated LV filling pressures • 5 yr survival: 50%, 50%, 20% • Survival is not impaired if no symptoms but symptoms related to severity Physical Exam • Carotid upstroke : reduced and a shudder on upstroke; transmitted murmur • SEM upper LSB and RSB radiating to the neck and carotid (R) – May be heard at LLSB – Thrill; A2 reduced, paradoxical splitting • Congestion and edema are late findings unless rheumatic • Rhythm is sinus unless late or RHD IMAGING THE VALVE IN AS • 2D: – SAX: 3 chunks of calcium that barely move: works better with TEE where AVA can be planimetered – LAX: 2 chunks of calcium that barely move Peak gradient overestimates gradient Mean gradient agrees well with invasive gradients. LVOT/AV VELOCITY Stages of Valvular Aortic Stenosis Stage A Definition At risk of AS Valve Anatomy ● ● B Progressive AS ● ● Bicuspid aortic valve (or other congenital valve anomaly) Aortic valve sclerosis Mild-to-moderate leaflet calcification of a bicuspid or trileaflet valve with some reduction in systolic motion or Rheumatic valve changes with commissural fusion Valve Hemodynamics ● Aortic Vmax <2 m/s ● ● Mild AS: Aortic Vmax 2.0–2.9 m/s or mean P <20 mm Hg Moderate AS: Aortic Vmax 3.0–3.9 m/s or mean P 20– 39 mm Hg Hemodynamic Consequences ● None ● ● Early LV diastolic dysfunction may be present Normal LVEF Symptoms ● None ● None Stages of Valvular Aortic Stenosis Stage Definition Valve Anatomy C - Asymptomatic severe AS C1 Asymptomatic ● Severe leaflet severe AS calcification or congenital stenosis with severely reduced leaflet opening C2 Asymptomatic severe AS with LV dysfunction ● Severe leaflet calcification or congenital stenosis with severely reduced leaflet opening ● ● ● ● ● Valve Hemodynamics Hemodynamic Consequences Aortic Vmax 4 m/s or mean P ≥40 mm Hg AVA typically is ≤1 cm2 (or AVAi 0.6 cm2/m2) Very severe AS is an aortic Vmax ≥5 m/s, or mean P ≥60 mm Hg Aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s or mean P ≥40 mm Hg AVA typically is ≤1 cm2 (or AVAi 0.6 cm2/m2) ● Symptoms ● ● LV diastolic dysfunction Mild LV hypertrophy Normal LVEF None– exercise testing is reasonable to confirm symptom status ● LVEF <50% ● None ● Stages of Valvular Aortic Stenosis Stage Definition Valve Anatomy D - Symptomatic severe AS D1 Symptomatic ● Severe leaflet severe highcalcification or gradient AS congenital stenosis with severely reduced leaflet opening D2 Symptomatic severe lowflow/lowgradient AS with reduced LVEF ● Severe leaflet calcification with severely reduced leaflet motion Valve Hemodynamics ● Aortic Hemodynamic Consequences Vmax ≥4 m/s, or mean P ≥40 mm Hg ● AVA typically is 1 cm2 (or AVAi 0.6 cm2/m2), but may be larger with mixed AS/AR ● LV ● AVA 1 ● LV cm2 with resting aortic Vmax <4 m/s or mean P <40 mm Hg ● Dobutamine stress echo shows AVA 1 cm2 with Vmax 4 m/s at any flow rate diastolic dysfunction ● LV hypertrophy ● Pulmonary hypertension may be present diastolic dysfunction ● LV hypertrophy ● LVEF <50% Symptoms ● Exertional dyspnea or decreased exercise tolerance ● Exertional angina ● Exertional syncope or presyncope ● HF, ● Angina, ● Syncope or presyncope Stages of Valvular Aortic Stenosis Stage Definition Valve Anatomy D - Symptomatic severe AS D3 Symptomatic ● Severe leaflet severe lowcalcification gradient AS with severely with normal reduced leaflet LVEF or motion paradoxical low-flow severe AS Valve Hemodynamics ● AVA 1 cm2 with aortic Vmax <4 m/s, or mean P <40 mm Hg ● Indexed AVA 0.6 cm2/m2 and ● Stroke volume index <35 mL/m2 ● Measured when the patient is normotensive (systolic BP <140 mm Hg) Hemodynamic Consequences ● Increased LV relative wall thickness ● Small LV chamber with low-stroke volume. ● Restrictive diastolic filling ● LVEF ≥50% Symptoms ● HF, ● Angina, ● Syncope or presyncope AVA by TEE NATURAL PROGRESSION OF AS • Yearly progression – 0.32 m/s/yr – 7 mm Hg/yr (mean gradient) – 0.12 cm2/yr loss of AVA • If peak velocity > 4m/s, 21% 2yr survival without AVR • If mild, moderate, or severe AS, repeat studies in 3-5, 1-2, 6 months-1 year MEDICAL THERAPY OF AS • Treat hypertension and increased lipids – Benefit to treating hypertension as it reduces total hemodynamic load – Benefit for hyperlipidemia relates more to concomitant CAD and not progression of AS • • • • Angina: none Syncope: limit activity CHF: diuresis, digoxin?? Valvuloplasty: works for 6 months – Bridge for noncardiac surgery – Short term symptom relief Indications for Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Aortic Stenosis Aortic Stenosis: Choice of Surgical or Transcatheter Intervention Recommendations COR LOE Surgical AVR is recommended in patients who meet an indication for AVR (listed in Section 3.4) with low I A or intermediate surgical risk For patients in whom TAVR or high-risk surgical AVR is being considered, members of a Heart Valve Team I C should collaborate closely to provide optimal patient care TAVR is recommended in patients who meet an indication for AVR for AS who have a prohibitive I B surgical risk and a predicted post-TAVR survival >12 months Aortic Stenosis: Choice of Surgical or Transcatheter Intervention (cont.) Recommendations COR LOE TAVR is a reasonable alternative to surgical AVR for AS in patients who meet an indication for AVR and IIa B who have high surgical risk Percutaneous aortic balloon dilation may be considered as a bridge to surgical or transcatheter IIb C AVR in severely symptomatic patients with severe AS TAVR is not recommended in patients in whom the III: No B existing comorbidities would preclude the expected Benefit benefit from correction of AS Etiology of Chronic Aortic Regurgitation • 9-14% of all valve disease with a male predominance • Valvular – Usual Causes of AS (including bicuspid due to prolapse and incomplete closure) – Rheumatic – VSD – Myxomatous degeneration of leaflets – SLE, RA, Ankylosing Spondylititis – Endocarditis • Aortic Root (increasing in past few years and >50%) Etiology of Chronic Aortic Regurgitation • Valvular • Aortic Root-dilatation of the root pulling leaflets apart and may lead to changes in valve cusps from the stress and additional AR – – – – – – – Age related and hypertension Cystic medial necrosis-including Marfans’ Disease Associated with bicuspid valve disease Subaortic stenosis Aortitis Giant Cell arteritis Aortic Dissection PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • LV response to AR: Both preload and afterload response – Entire stroke volume ejected into high pressure chamber. Compensation provided by increased end diastolic volume. LV dilates to >6cm for EDD – Eccentric LVH to normalize wall stress but results in increased collagen content; PWT usually < 13 mm • Adaptation results in the LV acting as a high compliance pump with little change in LVEDP • Over time, wall thickening does not keep pace with end diastolic wall stress resulting in afterload mismatch and EF falls, LV volume and LVEDP rises. Pathophysiology of Acute AR • Large regurgitant volume reenters a small noncompensated LV • Acute volume overload dilates the LV leading to high LVEDP • Early mitral valve closure as LVEDP exceeds LAP-may get diastolic MR • Pulmonary edema • Increase demand, shortened diastolic filling time, low diastolic pressures reducing coronary perfusion pressure resulting in reduced coronary blood flow and ischemia • Reduced LV function may ensue Pathophysiology of Acute AR CHRONIC AORTIC REGURGITATION: History has similarities to AS • Asymptomatic for long periods of time-symptoms develop with myocardial ischemia or reduced cardiac reserve • Angina-difficult to perfuse thickened myocardium; especially with a dilated cavity with increased wall stress and low diastolic pressures • Dyspnea on exertion: hypertrophy and fibrosis result in elevated LV filling pressures with exertion. Often LVEF still preserved • Palpitations can be troublesome due to ventricular ectopy and a sense of pounding in the chest due to volume overload. Syncope is arrhythmia related. PHYSICAL EXAM • Carotid upstrokes are increased and are bisfierens (bifid) • Displaced and diffuse PMI - thrill may be felt at the base • A2 is variable based on valve (soft) or root disease (normal) • Diastolic decrescendo murmur at the 3rd LICS or RICS. – Longer duration correlated with greater severity. Harsh systolic flow murmur is also heard at the base. – S3 may be heard at LV apex and early diastolic rumble (Austin Flint) • Peripheral pulses bounding and high pulse pressures (160/60); other peripheral signs of AR • Congestion and edema are late findings CHEST X-RAY and EKG Cardiomegaly is common finding Assessment by Echocardiography • • • • • Valve anatomy Root anatomy Demonstration of AR Quantification of AR Effect on chamber size Aortic Regurgitation Aortic Root Dilatation with Noncoronary Cusp Malcoaptation Natural History of Chronic Aortic Regurgitation • Normal LV function: 45% are asymptomatic at 10 years – 3.5% yearly rate of development of LV systolic dysfunction – 6% yearly rate of the development of LV systolic dysfunction or symptoms – Low sudden death rate if asymptomatic • • • • • If LV dysfunction-25% yearly rate to symptoms If symptoms 10% yearly mortality Angina-4 year survival Heart failure- 2 year survival Dujardin: 4 year survival with CHF=30% Survival in Chronic AR: NYHA Survival in Chronic AR: EF Management of Chronic AR • No endocarditis prophylaxis • Follow-up echocardiography for mild to moderate AR 12-24 months • Follow-up for severe AR with normal function every 6 months • Limit vigorous activity in patients with LV dysfunction and limited cardiac reserve • Treat hypertension to reduce regurgitant flow with nifedipine and ACEI • Treat rapid tachyarrhythmias vigorously as they are poorly tolerated Symptomatic AR • Treat heart failure in the standard fashion to stabilize patients and improve surgical risk – Digoxin may be more useful – Beta blockers may be less useful • Nitrates for angina may help (reduced LV filling pressures) • AVR is the preferred therapy Stages of Chronic Aortic Regurgitation (cont.) Stage C Definition Asymptomatic severe AR Valve Anatomy Valve Hemodynamics ● ● ● ● ● Calcific aortic valve disease Bicuspid valve (or other congenital abnormality) Dilated aortic sinuses or ascending aorta Rheumatic valve changes IE with abnormal leaflet closure or perforation ● o o o o o o o o Severe AR: Jet width ≥65% of LVOT Vena contracta >0.6 cm Holodiastolic flow reversal in the proximal abdominal aorta RVol ≥60 mL/beat RF ≥50% ERO ≥0.3 cm2 Angiography grade 3+ to 4+ In addition, diagnosis of chronic severe AR requires evidence of LV dilation Hemodynamic Consequences C1: Normal LVEF (50%) and mild-tomoderate LV dilation (LVESD 50 mm) C2: Abnormal LV systolic function with depressed LVEF (<50%) or severe LV dilatation (LVESD >50 mm or indexed LVESD >25 mm/m2) Symptoms ● None; exercise testing is reasonable to confirm symptom status Stages of Chronic Aortic Regurgitation (cont.) Stage D Definition Symptomatic severe AR Valve Anatomy ● ● ● ● ● Calcific valve disease Bicuspid valve (or other congenital abnormality) Dilated aortic sinuses or ascending aorta Rheumatic valve changes Previous IE with abnormal leaflet closure or perforation Valve Hemodynamics ● o o o o o o o o Severe AR: Doppler jet width ≥65% of LVOT; Vena contracta >0.6 cm, Holodiastolic flow reversal in the proximal abdominal aorta, RVol ≥60 mL/beat; RF ≥50%; ERO ≥0.3 cm2; Angiography grade 3+ to 4+ In addition, diagnosis of chronic severe AR requires evidence of LV dilation ● ● Hemodynamic Symptoms Consequences Symptomatic severe ● Exertional AR may occur with dyspnea or normal systolic angina, or function (LVEF more severe HF 50%), mild-tomoderate LV symptoms dysfunction (LVEF 40% to 50%) or severe LV dysfunction (LVEF <40%); Moderate-to-severe LV dilation is present. Indications for Aortic Valve Replacement for Chronic Aortic Regurgitation Bicuspid Aortic Valve • Bicuspid aortic valve disease is the most common congenital heart lesion, occurring in approximately 1% of persons. • Bicuspid aortic valve is associated with coarctation of the aorta, interrupted aortic arch, and Turner syndrome. • More than 70% of patients with a bicuspid valve will require AVR for AS or AR. • Progressive degenerative changes with premature calcification of the bicuspid valve generally lead to AS rather than AR occurring at an earlier age. 50% of AVR’s performed have bicuspid pathology. • Have a higher rate of valve-related complications with approximately 2% annually developing symptoms or needing cardiac surgery. Endocarditis may occur in 2% of patients Bicuspid Aortic Valve • Ascending aortic dilation may occur in persons with a bicuspid aortic valve, in combination with aortic valve disease independently. The aortopathy results from intrinsically abnormal connective tissue. • Serial evaluation of ascending aortic diameter should be performed by transthoracic echocardiography (or by CT or MR if not adequately visualized by echo). • Balloon valvotomy in patients <30 years without significant valvular calcification may offer intermediate-term benefit, thus delaying eventual AVR Bicuspid Aortic Valve • Surgery to replace the ascending aorta is indicated if diameter >4.5 cm due to progressive dilation. • Surgery to replace the ascending aorta is recommended in patients with a bicuspid aortic valve if the diameter of the aortic root or ascending aorta is >5.0 cm • After aortic valve replacement for bicuspid aortic valve disease, serial evaluation of the ascending aorta is still warranted. ETIOLOGY OF MITRAL STENOSIS • Rheumatic disease most common cause by far – – – – Leaflet thickening beginning at the edges of the leaflets Fusion of the commissures Produces significant narrowing of orifice Subvalvular involvement • Non-rheumatic - annular calcification extending down leaflets may also cause restricted motion • Congenital-single papillary muscle-parachute MV SAX-MITRAL VALVE Anatomic features of rheumatic mitral stenosis 1. Diffuse fibrous thickening of the margins of closure 2. Fibrous thickening involving the entire anterior and posterior leaflets producing leaflet rigidity 3. One or both valve commissures fuse reducing the size of the mitral orifice 4. Shortened, thickened, and fused chordae tendineae leading to subvalvular stenosis 5. Calcific deposits in one or both leaflets 6. Presence of Aschoff nodules in the myocardium PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • Restricted egress of blood out of LA • Increased LAP and pressure gradient through diastole with increased LA size – Increased with increased HR – Increased with increased venous return – Atrial fibrillation decreases LAP but increases rate • • • • Pulmonary venous hypertension and congestion RV dilatation due to pulmonary hypertension TV ring dilatation and TR Systemic venous hypertension History • Dyspnea on exertion progressing to orthopnea • Palpitations with dyspnea • Leg swelling • Abdominal swelling • Rare chest pain Cardiac Exam in Mitral Stenosis Inspection Malar flush Peripheral cyanosis (severe MS) Jugular venous distension (right ventricular failure) Palpation Parasternal right ventricular impulse Palpable pulmonary arterial impulse Palpable S1, P2, and occasionally, the diastolic rumble Auscultation Increased intensity of the first heart sound Opening snap Low-pitched diastolic rumbling murmur Mitral regurgitant murmur and TR Stages of Mitral Stenosis Stage C Definition Valve Anatomy Asymptomatic Rheumatic valve severe MS changes with commissural fusion and diastolic doming of the mitral valve leaflets Planimetered MVA ≤1.5 cm2 (MVA ≤1 cm2 with very severe MS) Valve Hemodynamics Hemodynamic Consequences MVA ≤1.5 cm2 Severe LA (MVA ≤1 cm2 with very enlargement severe MS) Elevated PASP Diastolic pressure >30 mm Hg half-time ≥150 msec (Diastolic pressure half-time ≥220 msec with very severe MS) Symptoms None Stages of Mitral Stenosis Stage D Definition Valve Anatomy Symptomatic Rheumatic severe MS valve changes with commissural fusion and diastolic doming of the mitral valve leaflets Planimetered MVA ≤1.5 cm2 Valve Hemodynamics MVA≤1.5 cm2 (MVA ≤1 cm2 with very severe MS) Diastolic pressure half-time ≥150 msec (Diastolic pressure half-time ≥220 msec with very severe MS) Hemodynamic Consequences Severe LA enlargement Elevated PASP >30 mm Hg Symptoms Decreased exercise tolerance Exertional dyspnea Indications for Intervention for Rheumatic Mitral Stenosis Mitral Regurgitation • Organic Causes – Mitral valve prolapse, rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, collagen vascular disease • Functional (resulting from left ventricular systolic dysfunction causing mitral annular dilation or restricted leaflet mobility). – Mitral regurgitation due to coronary artery disease • Ischemia • Papillary Muscle dysfunction or rupture • Focal or general LV dilatation causing mitral leaflet tethering and malcoaptation). MR-Pathophysiology • MRis generally progressive with increased preload with reduced or unchanged afterload due to low impedance to flow in LA • Eccentric hypertrophy accommodates the increased left ventricular filling volume and maintains forward stroke volume. • Increased left atrial pressure results in dyspnea and pulmonary hypertension, and progressive left atrial dilation with AF. • Progressive LV dilation may lead to systolic dysfunction. • In asymptomatic patients with chronic severe MR, either symptoms or LVdysfunction develops within 6 to 10 years. • In patients with acute severe MR, the lack of compensatory eccentric hypertrophy commonly results in fulminant symptoms of heart failure and possible cardiogenic shock. Pulmonary hypertension----Right heart dilatation and TR Mitral Valve Prolapse • Patients with MR due to MVP, present in 1%-2.5% of the population, are heterogeneous regarding spectrum of disease and associated manifestations. • Mitral valve prolapse is diagnosed by echocardiography with visualization of a displaced coaptation level of the anterior and posterior mitral leaflets >2 mm above the mitral annulus. • Patients with MVP generally have a benign prognosis, but some patients have symptoms of “mitral valve prolapse syndrome,” which include palpitations, nonanginal chest pain, fatigue, and dyspnea; • Patients with thickened mitral leaflets (≥5 mm) are at higher risk for progressive severe MR and complications. • In patients with flail mitral leaflets (lack of coaptation), the annual mortality rate is significantly higher than that for MVP with regurgitation, and earlier intervention should be considered. Doppler Echo SYMPTOMS • DOE • Other pulmonary congestive symptoms • Symptoms suggesting right heart failure – Leg swelling – Fatigue (RV dysfunction) • Palpitations (Arrhythmias)-atrial and ventricular PHYSICAL EXAM • • • • BP a bit low, irregular pulse JVD*, low volume carotids Crackles Displaced PMI, S3, filling murmur at apex, HSM radiating to axilla and occasionally LSB; RV tap*, Increased P2* • Liver enlarged* • Edema* *=Right heart failure LAB INVESTIGATIONS • EKG: LVH, LAA, MI, NASTT abn • CXR: cardiomegaly, LA enlargement, pulmonary congestion, increased PA size • Echo: – – – – Dilated LV, LA Right heart variable Valvular abnormality: Mitral valve competence Doppler: MR; TR Management of MR • Medical therapy has a limited role in organic MR. Symptomatic patients with acute severe MR should be promptly referred for cardiac surgery. In this situation, afterload reduction or IABP and stroke volume enhancement with inotropic agents may stabilize the patient before urgent cardiac surgery. • In patients with asymptomatic severe MR, no studies have demonstrated a clinical benefit with medical therapy. • In patients with functional or chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation with LV systolic dysfunction, treatment of the underlying heart failure with an ACE inhibitor or β-blocker may reduce severity of regurgitation, improve left ventricular function, and reduce cardiovascular events Stages of Primary Mitral Regurgitation (cont.) Stage C Definition Valve Anatomy Asymptomatic Severe mitral valve severe MR prolapse with loss of coaptation or flail leaflet Rheumatic valve changes with leaflet restriction and loss of central coaptation Prior IE Thickening of leaflets with radiation heart disease Valve Hemodynamics Central jet MR >40% LA or holosystolic eccentric jet MR Vena contracta ≥0.7 cm Regurgitant volume ≥60 cc Regurgitant fraction ≥50% ERO ≥0.40 cm2 Angiographic grade 3–4+ Hemodynamic Symptoms Consequences ● None Moderate or severe LA enlargement LV enlargement Pulmonary hypertension may be present at rest or with exercise C1: LVEF >60% and LVESD <40 mm C2: LVEF ≤60% and LVESD ≥40 mm Stages of Primary Mitral Regurgitation (cont.) Stage D Definition Valve Anatomy Symptomatic Severe mitral valve severe MR prolapse with loss of coaptation or flail leaflet Rheumatic valve changes with leaflet restriction and loss of central coaptation Prior IE Thickening of leaflets with radiation heart disease Valve Hemodynamic Hemodynamics Consequences Moderate or Central jet MR >40% LA or severe LA holosystolic enlargement eccentric jet MR LV enlargement Vena contracta Pulmonary ≥0.7 cm hypertension Regurgitant volume present ≥60 cc Regurgitant fraction ≥50% ERO ≥0.40 cm2 Angiographic grade 3–4+ Symptoms Decreased exercise tolerance Exertional dyspnea Stages of Secondary Mitral Regurgitation (cont.) Grade C Definition Valve Anatomy Valve Associated Hemodynamics Cardiac Findings Asymptomatic Regional wall Regional wall ERO ≥0.20 severe MR motion motion cm2 abnormalities Regurgitant abnormalities and/or LV volume ≥30 cc with reduced LV dilation with systolic function LV dilation and severe tethering systolic of mitral leaflet Annular dilation dysfunction due to primary with severe loss myocardial of central coaptation of disease the mitral leaflets Symptoms ● Symptoms due to coronary ischemia or HF may be present that respond to revascularization and appropriate medical therapy Stages of Secondary Mitral Regurgitation (cont.) Grade D Definition Valve Anatomy Symptomatic Regional wall severe MR motion abnormalities and/or LV dilation with severe tethering of mitral leaflet Annular dilation with severe loss of central coaptation of the mitral leaflets Valve Hemodynamics ERO ≥0.20 cm2 Regurgitant volume ≥30 cc Associated Symptoms Cardiac Findings Regional wall HF symptoms motion due to MR abnormalities persist even after with reduced LV revascularization systolic function and optimization LV dilation and of medical systolic therapy dysfunction due Decreased to primary exercise myocardial tolerance disease. Exertional dyspnea Indications for Surgery for Mitral Regurgitation Tricuspid Valve Disease • Tricuspid stenosis is uncommon caused predominantly by rheumatic heart disease. Severe stenosis leads to RAP elevation, atrial flutter, and systemic venous congestion (edema, hepatomegaly, ascites). • Tricuspid regurgitation associated with abnormal leaflets include – – – – – – – – Rheumatic heart disease Infective endocarditis Carcinoid tumor, Ebstein’s anomaly Radiation therapy Connective tissue disease Prolapse Trauma and pacer and defibrillator leads Tricuspid Valve Disease • Functional tricuspid regurgitation commonly is present in patients with pulmonary hypertension, due to the increased right ventricular systolic pressure and right ventricular dilatation. – Valve disease – CAD and LV dysfunction with MR – HFPEF • The appropriate timing of surgical intervention (repair or replacement) for severe tricuspid regurgitation is controversial, but is generally considered for patients with right-sided heart failure symptoms refractory to medical therapy or is performed concomitantly with mitral valve surgery Endocarditis • Infective endocarditis is a bacterial or fungal infection of the endocardium, including native or prosthetic valves, the endocardial surface, or an implanted cardiac device. • Endocarditis generally is caused by bacteremia with adherence of bacteria to a preexisting endocardial, particularly valvular, lesion. – Streptococcal infection was the predominant cause in earlier eras, staphylococcal infection is now the leading cause owing to the increase in health care–related invasive procedures and intravascular access. – As a result, duration of symptoms before presentation is shorter. Despite advancements in the diagnosis and therapy for endocarditis, the in-hospital mortality rate remains high, at nearly 20%. Endocarditis • Infective endocarditis should be suspected with a new or increased regurgitant heart murmur along with signs or symptoms of infection or bacteremia. Blood cultures may be negative if antibiotics are started before cultures are taken or if fastidious organisms. • Echocardiography has a primary role in the diagnosis of endocarditis. The modified Duke criteria for diagnosis of endocarditis include typical bacteriologic evidence in blood cultures or valve specimens, clinical findings, and echocardiographic evidence of endocardial involvement (new or worsening valve regurgitation, vegetation, paravalvular abscess, or leaflet perforation). – TTE has less sensitivity than TEE for the detection of endocardial involvement. – TEE has very high sensitivity and specificity for these diagnostic findings and complications of endocarditis (intracardiac abscess, fistula). – It may be an acceptable primary diagnostic test without previous TTE in certain clinical situations: intermediate or high pretest probability of endocarditis; patients with prosthetic heart valves; and evaluation for complications of endocarditis, such as intracardiac abscess, valve perforation, or fistula formation. Endocarditis • Empiric antibiotic therapy is appropriate after multiple blood cultures have been drawn when clinical suspicion for endocarditis is intermediate or high. • Tailored antibiotic therapy is guided by the causative organism and its susceptibilities. • Surgery during the index hospitalization is performed in nearly 50% of patients with valvular infective endocarditis and a higher percentage of those with cardiac device infective endocarditis. • Indications for surgery include: – (1) Severe hemodynamic perturbation, p related to severe left-sided valvular regurgitation or fistula formation and resultant heart failure; – (2) Evidence or likelihood of persistent infection despite appropriate antibiotic therapy (including persistent bacteremia or intracardiac abscess, or involvement of a prosthetic surface) – (3) Evidence or high risk of recurrent embolic event because of a large vegetation. Prosthetic Valves • • • • • For patients requiring valve replacement surgery, options for the type of prosthetic valve are biologic (xenograft or homograft) or mechanical valves. The major consideration regarding these types of valves is structural valve deterioration of biologic valves versus the need for life-long anticoagulation for mechanical valves. Biologic valve durability is dependent on the position of implantation, with greatest durability in right-sided valve replacements, followed by aortic and mitral positions. In the most common aortic location, the anticipated duration is 14 to 20 years before significant structural deterioration occurs. Other factors in this choice include hemodynamic performance and patient preference. Recommendations for Prosthetic Valves Mechanical Aortic Mitral Bioprosthetic Mechanical valve present in other valve location Age <65 years in the absence of contraindications to anticoagulation Age ≥65 years without other risks for thromboembolism Contraindication to anticoagulation Patient preference Age <65 years Age ≥65 years Contraindication to anticoagulation Patient preference Prosthetic Valves and Antithrombotic Regimens • • • After implantation of either a biologic or mechanical prosthetic valve, anticoagulation with warfarin is recommended for at least 3 months to allow endothelialization of the prosthetic material (not often done). In addition, all patients should receive aspirin (75-100 mg/d) to further reduce the risk for thromboembolic events. After 3 months, patients with a biologic valve replacement who are at low risk for thromboembolic events can discontinue warfarin but must remain on aspirin indefinitely; Patients with a mechanical valve replacement should continue taking low-dose aspirin and warfarin indefinitely (goal INR range 2.0-3.0 for aortic valve replacement and 2.5-3.5 for mitral valve replacement). Bridging Anti-Thrombotic Therapy • • Patients with mitral mechanical prosthetic valves are at higher risk for valve thrombosis. Additional risk factors for thrombosis are AF, previous thromboembolism, LV systolic dysfunction, hypercoagulable conditions, non bileaflet valves, mechanical tricuspid valve, or >1 mechanical valve. Patients with a mechanical mitral or a mechanical aortic valve with additional risk factors undergoing an elective surgical procedure requiring warfarin cessation should be bridged (unfractionated heparin IV or LMW heparin before and after the procedure. Prosthetic Valves • • • • For patients with HIT, bivalirudin may be used for bridging of anticoagulation. In patients at low risk of valve thrombosis (bileaflet mechanical aortic valve replacement with no risk factors for thrombosis), warfarin may be stopped 48 to 72 hours before the elective procedure and restarted within 24 hours after the procedure. Thrombosis of a mechanical valve is an emergent situation associated with a high risk for pulmonary edema and thromboembolism, and therapeutic options include repeat cardiac surgery or intravenous fibrinolytic therapy. For baseline assessment, all patients undergoing valve replacement surgery should have annual clinical evaluation and transthoracic echocardiography performed 2 to 3 months after implantation. Subsequently, however, routine annual echocardiography is not indicated if no change in clinical status has occurred.