* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 3.1) Ch. 2 Lecture PowerPoint

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

Pontic Greeks wikipedia , lookup

Historicity of Homer wikipedia , lookup

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of Greece and the Greek world wikipedia , lookup

Corinthian War wikipedia , lookup

Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Persian Wars wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

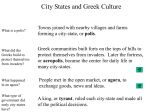

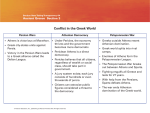

The Contest for Excellence Greece, 2000-338 B.C.E. The Contest for Excellence The Big Picture Archaic Age Classical Age Mycenaeans Minoans 2000 B.C.E. Colonization Trojan War 1000 B.C.E. Peloponnesian War Persian War 400 B.C.E. 2 The Contest for Excellence The Big Question How and why did the Greeks develop a politics and culture so distinctly different from the ones that evolved in the Ancient Middle East? 3 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes The Greek Peninsula THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE PENINSULA—MOUNTAINOUS WITH NO LARGE RIVERS—TENDED TO MAKE COMMUNITIES DEVELOP IN ISOLATION. GREEKS WERE OFTEN ORIENTED TOWARD THE SEA. 4 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E. – Wealthy and powerful civilization emerges on the island of Crete ca. 2000 B.C.E. – Not Greek, but a Semitic people. – Great city of Knossos is best known to us, which probably had roughly 40,000 living there at its height. – Traded with Fertile Crescent, learned to make Bronze from Sumerians, and built the best ships. – Minoan Palaces: Mazes of storerooms, leading to the legend of the labyrinth and Minotaur . Not symmetrical like most Mesopotamian and Egyptian architecture. – Myth of Theseus: The half-man, half-bull may have been the King of Knossos wearing a bull headress killed by a Greek. 5 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E. Greek representation (ca. 550 B.C.E. of Theseus and the Minotaur): 6 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E. – Developed a pictographic script like Sumerian cuneiform etched in clay tablets that we call “Linear A,” which scholars have yet to translate, but appears to have been used for accounting. – Palaces decorated with brilliantly colored frescoes. – Religion focused on a fertility goddess depicted holding snakes. – Religious ritual involved leaping over bulls; may have been an early precursor to bullfighting, ending with sacrifice. – Volcanic explosion on Thera (Santorini) may have ended Minoan civilization around 1450 B.C.E., but scholars debate the timing. – Whatever happened, the center of Aegean civilization passed to the Greeks. 7 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes The Minoans, 2000-1450 B.C.E. Fresco of Minoan bull-leaper, ca. 17th to 15th century B.C.E.; statue of Minoan Snake Goddess, ca, 1600 B.C.E. 8 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes • Mycenaean Civilization: The First Greeks, 2000-1100 B.C.E. – Indo-European Greek-speaking people invaded the Greek peninsula sometime after 2000 B.C.E. – Excavation of shaft-graves have uncovered crowns and masks in the Indo-European style. – Middle Eastern writer referred to these people as the “warmad Greeks” during this period. – Imitated Minoan art and writing system, creating their own that we call “Linear B.” 9 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes • Mycenaean Civilization: The First Greeks, 2000-1100 B.C.E. Gold Mycenaean Death Mask 10 Extent of Mycenaean Culture 11 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes Mycenaean Civilization: The First Greeks, 2000-1100 B.C.E. – Arose to commercial dominance in the Mediterranean after the fall of the Minoans, ca. 1450 B.C.E. – Built large palaces that had considerable fortifications—unlike those of the Minoans— suggested constant warfare – Mycenaean pottery found across the Mediterranean, as had Minoan. – Mycenaeans definitely were involved in raids and movements of people around 1200 B.C.E. that disrupted trade and brought on the Iron Age in Mesopotamian cultures. – According to Greek legend, the Mycenaean invasion of Troy took place around 1250 B.C.E., creating the basis for Homer’s epic poem, The Illiad, which details the heroics of the Trojan War. – Greek legend attributes the ten-year absence of Mycenaean warriors during the war to the fall of Mycenaean civilization. – More likely caused by drought, famine, and invaders from the north known as Doric 12 Greeks The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes From “Dark Ages” to Colonies • The “Dark Ages,” the period from 1100 to 750 B.C.E., is called such because of a lack of written record (scholars have translated Mycenaean “Linear B,” unlike Minoan “Linear A”). • Around 800 B.C.E., the blind poet Homer supposedly recorded some of the oral traditions that had passed down through the Dark Ages. • Renewed trade in olive oil, wine, and other goods seemed to help bring an end to the Greek isolation of the Dark Ages. • Greeks colonize places around the Mediterranean rim to escape famine and political turmoil on the Greek peninsula, and later may have done so to escape overcrowding. 13 The Greek Colonies in About 500 B.C.E. 14 The Rise and Fall of Ancient Heroes From “Dark Ages” to Colonies • Values of the “Heroic Society”—one that values individual honor, reputation, and prowess—from Mycenaean culture were preserved through Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. • Arête – the highest value in Homeric literature, meaning manliness, courage, and excellence. Competitive contests were the best proving ground for this trait, with it be warfare or athletic events. The Greeks thought this competitive quality separated them from the barbaroi. • Kouros and Kore: Male and female sculpted figures that increasingly became realistic and glorified individual human perfection. 15 Emerging from the Dark: Heroic Beliefs and Values Kouros and Kore figures, both ca. 530 B.C.E. How do these compare to similar Egyptian figures? 16 Emerging from the Dark: Heroic Beliefs and Values The Family of the Gods – Greek historian Herodotus (482 – 425 B.C.E.) claims that poets Homer (ca. 800 B.C.E.) and Hesiod (ca. 750 B.C.E.) had enormous influence on the future development of Greek religion. – Hesiod’s Works and Days describes daily life emerging from the Greek Dark Ages; his Theogony provides stories of the origins of the Greek gods, as well as mankind. – Primary Gods: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Apollo, and Demeter, who lived on Mount Olympus and behaved as poorly as regular humans: they were jealous, committed adultery, stole, and deceived. – Religious rituals were not somber affairs, but had the air of celebration. – Religious institutions did not become the center of Greek society, as they had in Sumer, Egypt, etc. 17 Emerging from the Dark: Heroic Beliefs and Values The Family of the Gods – Oracles were the religious class in ancient Greece, with the Delphic oracle of Apollo being foremost; they went into trances possibly brought upon by ethane gas that would allow visions that often had very ambiguous interpretations. – King Croesus of Lydia asked the Delphic oracle around 546 B.C.E. about Persian King Cyrus, and was told that a might empire would fall if he went to war with the Persians, not realizing the oracle had meant his own. – Later Greeks added Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility, to the list of Homer’s Olympians, acknowledging the role of irrationality in human life. – Hubris: While their gods had human qualities, Greeks warned humans of being so arrogant as to think themselves god-like. Those who acted with this quality—called hubris—were setting themselves up for a big downfall, a theme that emerges frequently in Greek drama. 18 Emerging from the Dark: Heroic Beliefs and Values Studying the Material World – Love of rational search for wisdom: philosophy – Greek faith in human reason to figure out the natural world – Thales (ca. 624 – 548 B.C.E.): Studied Mesopotamian and Egyptian astronomy and predicted and eclipse; he though everything was fundamentally derived from water. – Democritus (ca. 460 – 370 B.C.E.): Came up with the idea of infinite universe composed of tiny particles he called atoms; he was seen as wrong until early twentieth-century physicists proved him at least generally correct. 19 Emerging from the Dark: Heroic Beliefs and Values Studying the Material World – Pythagoras (ca. 582 – 507 B.C.E.): Developed the Pythagorean Theorem, demonstrating the relationship of angle widths within a triangle; also was the first to propose that the earth and other heavenly bodies were spherical and rotated on their axes. – Practical Applications: Sixth-century engineer Eupalinus constructed a 3,000-foot tunnel through a mountain using geometric insights. – Fears of “Impiety”: 432 B.C.E. Athenian law made it illegal to study the material world at the expense of denying the gods; the law was precipitated by philosopher Anaxagoras’s idea that the sun was a whitehot stone rather than a god. 20 Life in the Greek Poleis – Post Dark Ages: An emerging urban middle class of merchants and artisans has no loyalties to aristocratic landowners. – Hoplite Armies: Intense trade makes metal weapons, armor, and shields more affordable and in reach of citizen-soldiers. City dwellers are no longer reliant on aristocratic warriors for protection. They fight in phalanx formations, with long spears jutting out from tightly packed shields. 21 Life in the Greek Poleis The Invention of Politics – Tyrants: Between 650 and 550 B.C.E., many civil wars break out as lower classes overthrow the aristocrats. New rulers called tyrants emerged who ruled by force rather than hereditary or constitutional right. – Middle classes who controlled trade and fought as hoplites began to take charge of politics in city-states (poleis). – Poleis frequently had a fortified high ground called an acropolis and a market/gathering place called an agora. – City-states simultaneously began to develop varying representational styles of government, from an early form of democracy in Athens to an oligarchy (“rule of the few”) in Corinth. 22 Life in the Greek Poleis The Heart of the Polis – Economy: Oliver Harvesting, Craftsmanship, and Trade – Gymnasium: Physical prowess need to be cultivated as well as intellectual – the hoplite or “citizen-soldier” – Women’s Role: Upper-class women were expected to stay indoors; public life was for men alone (Spartan women were an exception) – Greek society depended heavily on slave labor; slaves’ situation ranged from skilled work in which they could retain some of their pay to harsh labor in mines 23 Life in the Greek Poleis Fears and Attachments in Greek Emotional Life – Bisexual Relations: Extreme separation of men and women created some anxiety in gender relations and made bisexuality common; Greeks often thought male-male love could be the purest form of love – Sappho of Lesbos: Sixth-century B.C.E. female poet from the isle of Lesbos who wrote about her passion for women; the word lesbian derives from her. – Courtesans: Prostitutes were accepted and even registered and taxed by many Greek city-states; they drank and mingled with powerful men while “respectable” women stayed home. 24 Life in the Greek Poleis Athens: City of Democracy – Oligarchy: By 700 B.C.E., Athenian aristocrats had developed a form of government that put the day-to-day businesses in the hands of a administrators called archons who were elected by an assembly of all male citizens called the Ecclesia. The archons were overseen by a council of senior and powerful men called the Areopagus, which eventually numbered 300, and wielded real power. – Solon’s Economic Reforms: Around 600 B.C.E., Athenian society was becoming weakened by food shortages and economic woes. An Athenian aristocrat, Solon, was elected sole archon in 594. He instituted a wide array of economic reforms: he canceled or limited debts, stopped exportation of agricultural goods, and standardized weights and measures. – Solon’s Political Reforms: Paved the way for men gaining wealth through trade to access political power. He did not challenge the old aristocratic families, but opened up ways for the newly wealthy to be elected to the highest offices. He created a people’s court to check abuses by the archons. He weakened the power of the Areopagus by creating a rival Council of the 400. 25 Life in the Greek Poleis Athens: City of Democracy – Tyranny: Solon’s reforms were ultimately unsuccessful since each group started asking for more privileges, creating civil strife. Athens turned to tyranny—rule by force—to deal with this chaos, bringing Peisistratus to power in 560 B.C.E. He ruled until 527 B.C.E. and was Athens last tyrant. – Cleisthenes: The nobleman Cleisthenes who stood for popular interests proposed a Constitution in 508 B.C.E. which refined Solon’s reforms and brought an unprecedented level of direct democracy to the city. He redistricted the city so that the old alliances based on clan and geography could no longer control city offices. He made Solon’s Council of 400 to become the Council of 500, so that every clan affiliation could have equal representation (50 per lot). – Assessing Democracy: Athens was not a perfect democracy. Who was excluded from the political system? Women, slaves, and foreigners called metics who lived and worked within Athens and accounted for one-third of the city’s free population. The Council set the agenda for the Ecclesia to vote on; the later was composed of all free male citizens over thirty. – Ostracism: Yearly mechanism by which someone perceived as a threat to Athenian democracy could be banished for ten years if 6,000 people voted to do so. The names 26 were written on clay pottery shards. 27 Life in the Greek Poleis Sparta: Model Military State – Helots: Rather than negotiating and trading with surrounding peoples, Sparta conquered and enslaved them, calling them helots. – Strict Control through Might: Since the Spartans were outnumbered by the helots, they maintained control by imposing strict military rule. – Oligarchy: Authority was kept in the hands of the elders; Spartans had no use for Athenian democracy – Training of Boys: Sickly infants were left to die on the mountainside. Seven-year-olds taken away from families to train until they were 20 and lived in the barracks eating plain food until they were 30. – Spartan Women: Since men led an isolated soldierly existence, women conducted the affairs of the household and had unusual independence. 28 29 Life in the Greek Poleis Olympic Games – First pan-Hellenic Games held in honor in 776 B.C.E. – Greeks had different city-states, but they shared culture and religion: called themselves collectively Hellenes. – Started as a footrace, but events expanded to boxing, wrestling, chariot racing, and a pentathlon: long-jump, javelin, discus, wrestling, and a 200-meter sprint. – Spectators flocked to the games, which also included a celebration in honor of Zeus and performance of dramas. – The Games were a safe way for the city-states to compete. – Women were not allowed to compete, but occasionally they held their own games in honor of Hera, wife of Zeus. 30 Life in the Greek Poleis Persian Wars (490 – 479 B.C.E.) – In 499 B.C.E., a Greek city-state colony in Asia Minor, Miletus, rebelled against the Persians, and Athens sent 20 ships in its defense: not enough to save the city, but enough to anger the Persians. – In 490 B.C.E., Persian King Darius sailed with a fleet across the Aegean and landed near Athens to punish it for helping Miletus. – Athenian soldiers met the Persians on the Plain of Marathon and were vastly outnumbered. However, Athenian general Militiades managed to outflank the Persians and made a running advance, which surprised the Persians. Texts claim that 6,400 Persians died compared to 192 Athenians. – The fast runner Philippides ran 150 miles in two days to request the help of the Spartans. Legend has it that he ran 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news of victory and then died; this is probably just a myth. – The small polis winning a victory over a huge empire gave Athens enormous prestige in Greece. 31 Life in the Greek Poleis Persian Wars (490 – 479 B.C.E.) – Ten years after Marathon, Darius’s successor, Xerxes, plotted a full-scale invasion of the Greek mainland, building a pontoon bridge across the Hellespont and brining 180,000 soldiers to Greece. His men built a canal in northern Greece so that his troops could be supplied; archaeological proof of the canal’s existence was recently uncovered. – Several city-states in the north surrendered to the massive invading army. – Athenians built up their fleet in attempt to control the Aegean and disrupt Persian supply routes, and also secured the help of Sparta and its allies. – Thermopylae: The Greeks forced the huge Persian forces to go through a narrow pass and seemed to be winning until a Greek traitor led the Persians around the defended pass so that they could attack the Greeks from behind. The Spartans stayed behind and fought to the death, totally outnumbered. – Athenians fled their polis in their ships, and were able to trap the Persian fleet in the narrow Athenian harbor as the latter sacked and burned the city and attacked the ground forces as well. – A year later, the Spartans led a coalition that destroyed the last remnants of the Persian Army. – The historian Herodotus later wrote a 600-page detailed history of the conflict that in many ways was the first modern work of history. His main theme was Greeks versus the “barbarians”—the superiority of the Greeks was proven by their capacity to defeat a much 32 larger force. The Persian Wars, 490-479 B.C.E. 33 Greece Enters Its Classical Age • Athens Builds an Empire, 477-431 B.C.E. – Delian League: In 477 B.C.E., many maritime poleis decide to create a defensive maritime league to protect trade. Each member contributed money to maintain a great fleet that patrolled the area around the sacred island of Delos, the supposed birthplace of Apollo. – Athens gradually asserts a dominant role in the League, essentially turning it into an empire with other members regarded as tribute or vassals to Athens. In 454, Athens moved the fleet’s treasury from Delos to Athens, which was very offensive to most Greeks. – Pericles (495-429 B.C.E.) was in many ways the architect of the Athenian golden age, was elected as strategoi in 443 B.C.E. – Pericles’ Democracy: Took measures to ensure that even poor citizens could participate in democratic institutions. 34 ©2011, The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 35 Greece Enters Its Classical Age Artistic Athens A modern rendering of the Parthenon, built 448-432 B.C.E. after the raid on the Delian treasury. 36 Greece Enters Its Classical Age Greek Architecture – Temples constructed on the post and lintel form. – By 600 B.C.E., Greeks had two different architectural “orders” for designs of columns: Doric (the oldest and simplest); the Ionic from the eastern Mediterranean. Later came the Corinthian, the most elaborate that used an acanthus leaf design (it was not used on the Acropolis). – Sculptures and reliefs on temples featured idealized people, not real human beings. 37 Greece Enters its Classical Age Greek Theater: Exploring Complex Moral Problems – Plays staged simply in outdoor theaters, with men playing both men and woman, and everyone wearing a simple mask. – Athenian playwright Aeschylus (ca. 525 – 456 B.C.E.) had fought at the Battle of Marathon, and his earliest play, The Persians, did not celebrate victory, but studied the Persian loss and warned against Athenians becoming hubristic. – Sophocles (ca. 496 – 406 B.C.E.) wrote a cycle called The Theban Plays around the figure of Oedipus, who moves from pride in being king of Thebes to humility and shame when he comes to realize he had killed his father and is sleeping with his mother. The play warned its viewers not to fall into complacency. 38 Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning The Peloponnesian War, 431-404 B.C.E. – Long destructive war between Athens and Sparta triggered by Sparta’s response to Athens’s aggressive behavior and its control of the Aegean Sea. – Sparta forms the Peloponnesian League to challenge the power of the Athenian Empire. – Athenians’ fortified access to the sea made it impossible for the Spartans to starve them out in a siege. Sparta had a land-based strategy, while Athens preferred to attack from the sea. Sparta did burn crops, and plague struck Athens in 430-429 B.C.E., during which time Pericles died. – Athenian morals declined during the war. The Athenians forced the islanders of Melos, who wanted to remain neutral, to become allies. Those on Melos refused, so Athenians slaughtered the men and enslaved the women and children. – Athens overextended its fleet when intervening in Sicily, and Persians helped the Peloponnesian League to strengthen its fleet, eventually leading to Athenian defeat in 404 B.C.E. – Historian Thucydides (460 – 400 B.C.E.) wrote an unusually unbiased account. 39 The Peloponnesian War, 431-404 B.C.E. 40 Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning Philosophical Musings: Athens Contemplates Defeat – Sophists: At the time of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.E.), this group of philosophers called for moral relativism, arguing that “man is the measure of all things,” and thus the individual needs to act on his or her own desires. – Socrates (ca. 470 – 399 B.C.E.): Argued against the moral relativism of the Sophists, using questioning to explore the nature of “right action.” In the disillusioned time after the war, Athenian authorities had little tolerance for those who focused on human inadequacies and moral flaws, so they brought Socrates up on charges of impiety and corrupting the young (partly because the traitor Alcibiades had been his student) and sentenced him to death. 41 Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning Philosophical Musings: Athens Contemplates Defeat – Plato (427 – 347 B.C.E.): This student of Socrates wrote many dialogues that preserved his mentor’s ideas and put them alongside his own. He believed that truth and justice only existed in the ideal world, and that people lived in the imperfect realm of the senses, only a shadow of true reality. He founded the Academy to teach young men about the ideal forms that existed outside of the human world and could only be accessed through philosophical training. He became disillusioned with the democracy that killed his teacher, and his The Republic, proposed an ideal state run by “philosopher-kings.” – Aristotle (384 B.CE. – 322 B.C.E.): He studied at Plato’s Academy but came to disagree with his teacher’s ideas about “ideal forms,” arguing that ideas cannot exist outside of their physical manifestations. Knowledge thus can only be acquired by studying the physical world. He divided up the pursuit of knowledge into several categories, many of which are still with us today, with the main ones being ethics, natural history, and metaphysics. He saw any type of government—monarchy, republic, or aristocracy—as potentially becoming 42 corrupt. A small polis with a strong middle-class would prevent extremes. Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning Tragedy and Comedy: Innovations in Greek Theater – Euripides (485 – 406 B.C.E.): His plays grappled with human anguish during he Peloponnesian War. The Trojan Women dealt with the grief of captured women, and was an implicit critique of the Athenian enslavement of the women of Melos. – Aristophanes (455 – 385 B.C.E.): Hi comedies used ridiculous costumes and crude humor to create biting social and political satire. In 411 B.C.E., he wrote Lysistrata, in which women go on a sex strike until their men stop fighting in the war. 43 Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning Hippocrates and Medicine Hippocrates (ca. 460 – 377 B.C.E.) was a key figure in developing the western tradition of medicine, replacing superstition in favor of careful scientific observation and rejecting the idea that bad spirits caused human ailments. 44 Destruction, Disillusion, and a Search for Meaning The Aftermath of War, 404-338 B.C.E. – Athens agrees to break down its defensive walls, keep a fleet of only twelve ships in its terms of surrender, and allow a Spartan garrison within the city. – Sparta proved a poor diplomatic manager of the alliance against Athens, particularly when it gave over the Greek states in Asia Minor to the Persians. – Greek city-states continued to fight amongst each other—like Corinth and Thebes—hastening the decline of the poleis. – In 404 B.C.E., Sparta imposed a brutal thirty-man oligarchy over Athens, which tried to stamp out the democratic forms. – Increasing use of Greek mercenaries weakened loyalties to the citystate. 45