* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download as a PDF

Swinging (sexual practice) wikipedia , lookup

Incest taboo wikipedia , lookup

Father absence wikipedia , lookup

Sexuality after spinal cord injury wikipedia , lookup

Body odour and sexual attraction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual objectification wikipedia , lookup

Hookup culture wikipedia , lookup

Sexual slavery wikipedia , lookup

Ages of consent in South America wikipedia , lookup

Heterosexuality wikipedia , lookup

Sexual addiction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual fluidity wikipedia , lookup

Age of consent wikipedia , lookup

Sexual abstinence wikipedia , lookup

Exploitation of women in mass media wikipedia , lookup

Sex and sexuality in speculative fiction wikipedia , lookup

Human mating strategies wikipedia , lookup

Ego-dystonic sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Penile plethysmograph wikipedia , lookup

Sexual racism wikipedia , lookup

Erotic plasticity wikipedia , lookup

Human male sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Age disparity in sexual relationships wikipedia , lookup

Sexual reproduction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual dysfunction wikipedia , lookup

Sexual selection wikipedia , lookup

Sex in advertising wikipedia , lookup

Sexological testing wikipedia , lookup

Rochdale child sex abuse ring wikipedia , lookup

Sexual stimulation wikipedia , lookup

Sexual ethics wikipedia , lookup

Human sexual response cycle wikipedia , lookup

History of human sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Slut-shaming wikipedia , lookup

Human female sexuality wikipedia , lookup

Lesbian sexual practices wikipedia , lookup

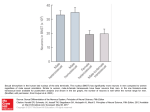

Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 30:263–276, 2004 Copyright © 2004 Brunner-Routledge ISSN: 0092-623X print DOI: 10.1080/00926230490422403 Communication and Associated Relationship Issues in Female Anorgasmia MARY P. KELLY, DONALD S. STRASSBERG, and CHARLES M. TURNER Department of Psychology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA Communication problems are among the most common complaints brought to couples’ counseling and are believed to play a central role in the development and maintenance of many sexual dysfunctions. The present study examined self-reported communication patterns within heterosexual couples where the wife is experiencing anorgasmia and within two groups of control couples. As hypothesized, couples with an anorgasmic female partner reported more problematic communication regarding issues of sexuality than did control couples. In particular, the anorgasmic women and their male partners reported significantly more discomfort than did controls in discussing sexual activities associated with direct clitoral stimulation. The etiologic and treatment implications of these differences are discussed. Problems in communication are among the most common complaints presented by couples seeking marital therapy (Fowers, 2001; Halford, Hahlweg, & Dunne, 1990; Schmaling & Jacobsen, 1990). Although communication has long been considered important to sexual satisfaction and adjustment (Cupach & Comstock, 1990; Delaehanty, 1983; Ferioni & Taffe, 1997; LoPiccolo, 1978; McCabe, 1999; McCarthy, 1995; Wheeless & Parsons, 1995; Zimmer, 1983), researchers have yet to demonstrate the specific nature of communication problems unique to sexually dysfunctional couples. This study was part of a larger project on couples’ communication. Address correspondence to Donald S. Strassberg, Department of Psychology, 580 S. 1530 E., Room 502, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84112, USA. E-mail: donald.strassberg@ psych.utah.edu 263 264 M. P. Kelly et al. COMMUNICATION AND ANORGASMIA A review of theoretical models of the etiology/maintenance of anorgasmia (Heiman & Grafton-Becker, 1989) argued that communication deficits, lack of confidence in communication, and inhibitions to communication are related to the disorder. Support for the importance of communication in female anorgasmia was found in a study by Kelly, Strassberg, and Kircher (1990). The strongest distinguishing characteristic of anorgasmic (versus orgasmic) women in this study was the report of significantly less anticipated communication comfort regarding direct clitoral stimulation activities (i.e., cunnilingus, manual genital stimulation of the woman). In contrast, no communication comfort differences were found with respect to intercourse-related activities. Direct clitoral stimulation activities have been suggested to be the most likely to maximize orgasmic responsiveness in women (e.g., Griffitt & Hatfield, 1985). Difficulties with communication regarding these activities could play a particularly important role in the etiology and maintenance of female anorgasmia. The literature reviewed offers little articulation of the nature of specific communication problems in couples with an anorgasmic female partner. Examining the minimal necessary conditions for the development of effective sexual stimulation suggests some preliminary hypotheses. Assuming a woman knows what she wants and needs sexually, she must then, at a minimum (a) be willing and able to express these wants and needs to her partner (MacNeil & Byers, 1997; Markman, Floyd, Stanley, & Storaasli, 1988) and (b) have a partner able and willing to be receptive to what she has to say (Halford et al., 1990). THE PRESENT STUDY In the present study, we explored the extent to which these and other elements in the communication process may distinguish couples with an anorgasmic female partner from sexually functional couples. The study employed both a problem-free and a nonsexual problem contrast group. On the basis of the research literature and the model described above, we hypothesized that, in general, the communication of couples with an anorgasmic female partner on sexual topics would be perceived by the couples as distinguishably more problematic than that of couples in the control groups. In particular, we anticipated that (a) anorgasmic women would report significantly less comfort than would orgasmic women in control groups in communicating with their partners about sexual activities involving direct clitoral stimulation, and (b) male partners of anorgasmic women would be significantly less accurate than the male partners of control group orgasmic women in estimating their partners’ sexual preferences. Communication and Anorgasmia 265 METHOD Participants Participants were 47 heterosexual couples recruited via campus and community newspapers and flyers, through physician referral, and through contact with patient affiliate groups (e.g., Diabetes Association of America). Approximately 25% of initial respondents met eligibility the criteria (described below) and completed the study. Three groups of participants were recruited on the basis of health and sexual functioning status as follows: (a) couples in which each partner reported being free of physical health problems and in which the female partner reported the absence of orgasmic response in sexual activity (of any kind) with her partner in greater than or equal to 70% of sexual interactions (Anorgasmic group, n = 14); (b) couples in which both partners reported being free of problems in their physical health or their sexual functioning (Problem-Free Control group, n = 16); and (c) couples in which either partner reported a chronic physical health problem (e.g, diabetes, heart disease, emphysema) and in which both partners reported being free of sexual functioning difficulties (Chronic Illness Control group, n = 17). Males were considered free of sexual dysfunction if they reported sexual functioning sufficient for intercourse and orgasm (male) in greater than or equal to 70% of sexual interactions with their partners (almost all were functional and orgasmic on 100% of occasions). Females were considered free of sexual dysfunction if they reported the ability to attain orgasm through some type of partner stimulation in at least 50% of sexual interactions. All participants were at least 18 years of age, involved in a relationship that they reported as “steady and sexually active” for at least 9 months, and reported an average frequency of sexual activity of at least once per week. No significant group differences were found for age (males 20–69, median = 33; females 20–56, median = 30); duration of relationship (10–186 months, median = 48 months); frequency of sexual activity (4–33 times per month, median = 11); relationship adjustment (as measured by an adapted version of the Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment Test [Locke & Wallace, 1959]; males median = 106, females median = 111). In 94% of couples participating, both partners were Caucasian. Couples were paid $20.00 and offered a didactic seminar on sexual enrichment for participating. Assessment INTERVIEWS Prescreening interview. Each member of responding couples was independently administered a prescreening interview via telephone to assess for 266 M. P. Kelly et al. initial eligibility. Couples meeting eligibility criteria were given an appointment for data collection. Sexual functioning interviews. Upon arriving in our laboratory, each partner was individually interviewed by a same-sex interviewer to assess the couple’s sexual functioning and behavior. These interviews focused on each partner’s assessment of the sexual stimulation activities in which they engaged and the perceived effectiveness of these activities. The primary purpose of these interviews was to ensure that all couples met the sexual functional eligibility requirements of their group placement. SELF-REPORT MEASURES The following measures were completed individually, in separate rooms, by both members of all participating couples. Sexual interaction inventory (SII; LoPiccolo & Steger, 1974). This instrument presents drawings of 17 different heterosexual activities and poses a number of questions about each. For each activity, the following question was added to those posed by the instrument: “How comfortable would you feel communicating with your partner about this activity (for example, discussing your feelings about it, suggesting trying it, or refusing to try it)?” We termed this the Communication Comfort Scale. The SII yields a profile of 11 subscales assessing a variety of sexual issues. Of these, six were of particular interest: (1 and 2) the two Perceptual Accuracy scales (male and female) measuring the discrepancies between each partner’s estimates of the other’s enjoyment of particular sexual activities and the other’s self-report of enjoyment of those activities, (3) Self-Acceptance, (4) Partner Acceptance, (5) Frequency Dissatisfaction, and (6) Pleasure Mean. Sexual communication inventory (SCI; Bienvenue, 1980). This 30-item self-report instrument assesses various aspects of sexual communication including the expression of sexual likes, dislikes, and desire for sexual interaction. Locke-Wallace marital adjustment test (MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959). A minimally adapted form of this well known measure was used to assess relationship adjustment. Procedure At the scheduled appointment, each participant was introduced to a same-sex interviewer who privately conducted the pre- and postquestionnaire Sexual Functioning Interviews. Between the interviews, each participant also individually completed the SII, SCI, and MAT. Participants were informed that information shared in interviews and questionnaires would not be revealed to their partner. Communication and Anorgasmia 267 RESULTS We examined the Communication Comfort and Perceptual Accuracy scales from the adapted SII via analysis of variance procedures to test hypothesized group differences in communication. Because sex specific hypotheses were being tested on these scales, we used separate one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to examine men and women across the three groups. We hypothesized that couples in the Anorgasmic group would evidence more generally problematic sexual communication than would control couples (i.e., no sex-specific hypotheses). Therefore, we examined the SCI scores via a 3 (Group) × 2 (Sex) repeated measures ANOVA. Communication Comfort Figures 1 and 2 present the mean Communication Comfort scores. The one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for Group for females, F (2,44) = 3.28, p < .05, on the Overall Communication Comfort score. Planned contrasts of scores of women in the Anorgasmic group (M = 4.60) versus the combination of women in Problem-Free Control (M = 5.38) and Chronic Illness Control (M = 5.50) groups revealed that, consistent with our prediction, women in the Anorgasmic group reported significantly ( p < .05) less anticipated Overall Communication Comfort related to talking with their partners about various sexual activities. We conducted further exploration of this finding. We computed subscales of Communication Comfort for participants’ responses on those items FIGURE 1. Communication comfort scores by group (females). 268 M. P. Kelly et al. FIGURE 2. Communication comfort scores by group (males). related to (a) direct clitoral stimulation (receiving either oral sex or manual genital stimulation) and (b) intercourse. We compared these scores via oneway ANOVAs for women in the three groups. Results of these analyses (see Figure 1) indicated a significant Group difference among women, F (2,44) = 4.64, p < .02, on anticipated Communication Comfort scores for direct clitoral stimulation activities, with a similar, but nonsignificant difference, F (2,44) = 1.29, p > .2, found on anticipated Communication Comfort scores for intercourse. A Neuman-Keuls test of Communication Comfort scores for females on the direct clitoral activities revealed that the mean for anorgasmic women (M = 4.18) was significantly lower ( ps < .05) than the means for women in each of the two control groups (Problem-Free M = 5.19, Chronic Illness M = 5.41). Although we offered no specific hypotheses with respect to how males in the study would score on the anticipated Communication Comfort measure, we analyzed results for males to generate preliminary findings on this variable. Analysis of variance results revealed a significant group difference for males, F (2,42) = 4.23, p = .02, similar to that found for females (see Figure 2). Neuman-Keuls analysis of this difference revealed that the male partners of anorgasmic women reported significantly less ( ps < .05) anticipated Overall Communication Comfort (M = 4.68) than the male partners of women in either of the two control groups (Problem-Free M = 5.50, Chronic Illness M = 5.49). Further exploration of this difference revealed a pattern identical to that of the women: Partners of the anorgasmic women reported less anticipated Communication Comfort than did the male controls for both direct clitoral and intercourse activities; however, the difference was significant ( p < .05) only for the direct clitoral stimulation activities (see Figure 2). Communication and Anorgasmia 269 FIGURE 3. Perceptual accuracy scores by group. Perceptual Accuracy An ANOVA, F (2,44) = 7.05, p < .005, and Neuman-Keuls procedure revealed that, as hypothesized, male partners of Anorgasmic women showed significantly less accuracy ( p < .05) than did the partners of both groups of orgasmic women in estimating their partner’s sexual preferences (Anorgasmic M = 18.73, Problem-Free M = 11.23, Chronic Illness M = 11.41, higher scores mean less accuracy). A similar, but nonsignificant, F (2,44) = 2.08, p = .14, pattern was seen for the women when we assessed their perception of their male partner’s preferences (see Figure 3). Sexual Communication Inventory We analyzed differences on the SCI via a 3 (Group) × 2 (Sex) ANOVA, followed by a planned contrast. Neither the Group nor Sex main effects nor their interaction reached statistical significance. However, the planned contrast comparing the average SCI scores for couples in the Anorgasmic group (M = 63.36, SD = 17.64) with the combination of averages of couples in the Problem-Free Control (M = 70.31, SD = 17.20) and Chronic Illness Control (M = 71.40, SD = 17.00) groups approached statistical significance (t = −1.88, p = .066), with the Anorgasmic couples reporting marginally poorer communication. ADDITIONAL SELF-REPORT MEASURES We conducted secondary analyses of the four remaining self-report scales of the Sexual Interaction Inventory (Self-Acceptance, Partner-Acceptance, 270 M. P. Kelly et al. TABLE 1. Sexual Interaction Inventory Means for Males and Females by Group Group Scale Self-acceptance Females Males Partner acceptance Females Males Pleasure Females Males Frequency dissatisfaction Females Males Anorgasmic Problem-free Chronic illness 18.91 (11.9)a 5.30 (4.00) 9.37 (6.5)b 4.00 (3.2) 5.75 (5.0)b 4.12 (4.5) 11.21 (7.5) 22.56 (11.7)a 8.90 (8.4) 11.0 (8.1)b 7.63 (6.8) 11.41 (10.8)b 4.33 (0.9)a 5.23 (0.4) 5.18 (0.4)b 5.44 (0.4) 5.24 (0.6)b 5.43 (0.7) 17.79 (9.3)a 22.66 (7.7)a 12.40 (8.9)a 15.12 (6.7)b 9.72 (6.2)a 11.63 (8.1)b Note. Means with different subscripts in the same row are significantly ( p < .05) different. Self-acceptance and Partner-acceptance: Maximum possible score = 85, higher scores = less acceptance. Pleasure: Maximum possible score = 6.0, higher scores = greater pleasure. Frequency dissatisfaction: Maximum possible score = 85, higher scores = greater dissatisfaction. Pleasure Mean, and Frequency Dissatisfaction) to provide descriptive information about participant groups on each of these variables. We conducted repeated measures ANOVAs on Group (3) by Sex (2) on each scale. These analyses revealed that women in the Anorgasmic group were less sexually self-accepting, F (2,44) = 10.62, p < .001, although not significantly less partner accepting, F (2,44) = .87, p > .40, than were women in the Problem-Free Control and Chronic Illness Control groups (see Table 1). Conversely, men with anorgasmic partners were significantly less partner sexually accepting, F (2,44) = 6.02, p < .01, but not significantly less sexually self-accepting, F (2,44) = .49, p > .60, than were men in either control group (see Table 1). Neither men nor women in the control groups differed significantly from each other on these variables. Anorgasmic females reported deriving significantly less pleasure, F (2,44) = 8.76, p < .001, from sexual activities than did women in the control groups, who did not differ significantly from each other (Anorgasmic M = 4.33, Problem-Free M = 5.18, Chronic Illness M = 5.24, higher scores mean more pleasure). The men in all three groups were not significantly different (F < 1) from each other in their reported sexual pleasure (see Table 1). Finally, consistent with results reported by LoPiccolo and Steger (1974), both men and women in the Anorgasmic condition reported significantly greater dissatisfaction with their current sexual frequency, F (2,44) = 8.43, p < .001 for males, F (2,44) = 3.82, p < .03 for females, than did their counterparts in both control groups (who, again, did not differ from each other). Communication and Anorgasmia 271 DISCUSSION Research to date has not provided a clearly articulated theoretical model for understanding or predicting communication patterns in couples with an anorgasmic female partner. The present study offers a beginning to the development of such a model by describing some of the dyadic features likely to be important in communication as it relates to sexual function or dysfunction. The major findings of the present study suggest that, consistent with our hypotheses as well as with previous research and clinical observations (Kilmann, 1984; LoPiccolo, 1978; MacNeil & Byers, 1997), couples with an anorgasmic female partner reported more troubled sexual communication than sexually functional couples. These distinguishably negative patterns were apparent even when compared with the communication of couples experiencing another serious problem area (such as chronic illness). Among the differences in communication predicted, the expectation that anorgasmic women would report lower levels of communication comfort than the orgasmic women in the control groups was supported. Furthermore, results of the present study replicate previous research (Kelly et al., 1990) in demonstrating that this difference relates most strongly to communication regarding direct clitoral stimulation activities (cunnilingus and manual genital stimulation of the female). Moreover, preliminary findings in the present study suggest that this pattern of lower communication comfort related specifically to direct clitoral stimulation activities is characteristic of the male partners of anorgasmic women as well. It is not clear why couples with an anorgasmic female partner may have particular difficulty discussing the sexual techniques (those involving direct clitoral stimulation) upon which many women rely for orgasmic responsiveness. However, impediments to communication about these activities are likely to interfere with the development of effective sexual stimulation that could improve the sexual responsiveness of anorgasmic women (Hulbert & Apt, 1995; Pierce, 2000). The fact that the same pattern is found in both the anorgasmic women and their partners underscores the importance of viewing and treating this sexual dysfunction in a couple format (Masters & Johnson, 1977). Further evidence of communication difficulties in the anorgasmic couples was revealed in the analyses of perceptual accuracy measures. As predicted, the male partners of anorgasmic women were significantly less accurate than their Problem-Free Control and Chronic Illness Control group counterparts in estimating their partners’ sexual preferences. This pattern, noted in previous research with sexually dysfunctional couples (the majority of whom suffered from female anorgasmia; Foster, 1978; Kilmann et al., 1984) has been found to be responsive to a sex therapy program that included a communication component (Foster, 1978). 272 M. P. Kelly et al. Both partners in the anorgasmic couples reported low acceptance of the woman’s (but not the man’s) sexual responsiveness. Although this is not surprising given that she was the symptomatic partner, it suggests that the locus of responsibility for sexual difficulties in these couples was seen by both partners to reside in the female. The notion that, at least in female anorgasmia, the woman is considered by both partners to be the “repository” of the problem may be an important dynamic in the development of female anorgasmia. At the very least, to the extent that partners share this belief, the psychological, relational, and sexual patterns resulting may be relatively immutable. The lack of difference between the men in the anorgasmic and control groups on the sexual self-acceptance scale is not consistent with previous research using this measure. Kilmann et al. (1984) found both males and females in couples with an anorgasmic female to manifest low self-acceptance, and Zimmer (1983) found low self-acceptance to be characteristic of men and women in couples with secondary sexual dysfunction (primarily of the female). Thus, the males in the present sample appear to be atypically selfaccepting. Neither Kilmann et al. (1984) nor Zimmer (1983) mention how their couples were recruited. If couples in the previous studies were targeted for treatment (either being referred from clinical settings or offered treatment as part of participation) they might be characteristically different than those participating in the present research. Our largely nonclinical recruitment procedures may have attracted couples where the partners of the anorgasmic women were atypically self-assured. Additional group differences consistent with previous research were found on other SII scales (Kilmann et al., 1984). Of all the women that we studied, those in the Anorgasmic group reported the lowest sexual Pleasure and greatest sexual Frequency Dissatisfaction (discrepancies between how often various sexual experiences occur and how often the participant would like them to occur). The male partners of anorgasmic women, although not significantly different from the other men in their reported experienced sexual Pleasure, did report a significantly greater degree of Frequency Dissatisfaction. This suggests that both members of the anorgasmic couples participating in the present research were substantially discontented with their current sexual repertoire. The exploration of this dissatisfaction for each partner and the processing of ideas for alleviating it may be fruitful avenues for clinical intervention. IMPLICATIONS FOR TREATMENT Results of the present study strongly support the notion that communication is related to sexual adjustment in a significant way (Cupach & Comstock, 1990; Ferioni & Taffe, 1997; LoPiccolo, 1978; McCabe, 1999; McCarthy, 1995; Rosen Communication and Anorgasmia 273 & Beck, 1988; Wheeless & Parsons, 1995). Consistent with most treatment recommendations for anorgasmia (e.g., Bancroft, 1989; Heiman & GraftonBecker, 1989), the present findings argue for a couple-oriented or systems approach to the treatment of this disorder. The observed communication difficulties and their interactive nature suggest communication barriers that are unlikely to be effectively and efficiently removed working only with the anorgasmic woman. The design of the present research does not allow for the formulation of causal explanations regarding the relationship between anorgasmia and communication problems. Although it is conceivable that the selfreported communication difficulties described by the anorgasmic couples resulted in or exacerbated sexual functioning problems, it is also quite possible that sexual functioning difficulties led to or exacerbated the communication problems evidenced. Alternatively, other factors (such as a history of sexual trauma or lack of sex knowledge) may have resulted in both the communication difficulties and in the sexual difficulties experienced by anorgasmic couples. At the very least, the existence of communication difficulties such as those revealed here would likely be to impede the resolution of the problem. If couples’ communication comfort level is not addressed, or if therapists do not consider that such comfort may vary among sexual topics, resistance and other impediments to treatment may be obscured. There have now been two studies (Kelly et al., 1990 and the present investigation) suggesting that couples with an anorgasmic female partner may evidence particular difficulty communicating about sexual techniques that provide relatively direct clitoral stimulation. This may help to explain the general effectiveness of directed masturbation training and clitoral stimulation oriented treatments for female anorgasmia (de Bruijn, 1982; LoPiccolo & Stock, 1986). These methods educate, provide vocabulary, and, when conducted in a couples format, provide opportunities to discuss this highly effective form of sexual stimulation (Cotten-Huston & Wheeler, 1983; Leiblum & Ersner-Hershfield, 1977). Based on the findings of the present study, it is likely that interventions addressing direct clitoral stimulation issues will be simultaneously challenging yet potentially powerful. Communication obstacles may be more evident in these interventions, but, if overcome, may result in greater improvement in sexual functioning. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY As with all sexuality research, the limitations of volunteer bias (e.g., Strassberg & Lowe, 1995) must be acknowledged. The couples studied may represent the least inhibited or most motivated for change of those with an anorgasmic female partner. Therefore, results found may not generalize to all female 274 M. P. Kelly et al. anorgasmic couples. These findings also may tell us little about communication in couples with other sexual dysfunctions. The employment of a problem control group offered the opportunity to examine sexual communication in couples with chronic, nonsexual problems. The Chronic Illness Control group employed in the present study, however, was an imperfect contrast in a number of ways. First, the group consisted of mixed health problems, some of which had greater impact on the participants than others. A group of participants with a uniform type and level of problem would have offered a more appropriate comparison. Furthermore, in the Chronic Illness Control group, the afflicted partner was sometimes the male, sometimes the female, and in one case both. Employing a comparison group of couples where the female was consistently the afflicted partner also would have allowed for a purer empirical comparison. Finally, these results are limited to self-report measures. The extent to which the perceived communication differences reported by these couples corresponds to measurable behavioral differences must yet be established. SUMMARY Theorists, researchers, and clinicians have long argued that problems in communication are characteristic of many couples’ difficulties, including sexual dysfunctions. The present study provides evidence consistent with this hypothesis. Couples with an anorgasmic female partner demonstrated a number of self-reported communication problems that distinguished them from our controls. It seems clear that each partner’s subjective experience of such communication and the effects of this experience on his or her motivations for continuing to engage in sexual communication are important areas for further study. Of course, the correlational nature of our study cannot distinguish whether the identified communication problems preceded, followed, or were related through another variable to the sexual problems. Irrespective of the direction of causality, the kinds of communication difficulties evidenced by the couples with an anorgasmic female partner certainly could help to maintain the dysfunction and, therefore, would be appropriate targets of therapeutic intervention. Such intervention would best be served by the treatment of the couple rather than just the symptomatic partner. REFERENCES Bancroft, J. (1989). Human sexuality and its problems (2nd ed). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Bienvenue, M. J., Sr. (1980). Counselor’s and teacher’s manual for the secual communication inventory. Saluda, NC: Family Life Publications. Communication and Anorgasmia 275 de Bruijn, G. (1982). From masturbation to orgasm with a partner: How some women bridge the gap—And why others don’t. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 8, 151– 167. Cotten-Huston, A. L., & Wheeler, K. A. (1983). Preorgasmic group treatment: Assertiveness, marital adjustment, and sexual function in women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 9, 296–302. Cupach, W. R., & Comstock, J. (1990). Satisfaction with sexual communication in marriage: Links to sexual satisfaction and dyadic adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 179–186. Delaehanty, R. (1983). Changes in assertiveness and changes in orgasmic response occurring with sexual therapy for preorgasmic women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 8, 198–208. Ferroni, P., & Taffe, J. (1997). Women’s emotional well-being: The importance of communicating sexual needs. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 12, 127–138. Foster, A. L. (1978). Changes in marital sexual relationship following treatment for sexual dysfunctioning. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 4, 186–197. Fowers, B. J. (2001). The limits of technical concept of a good marriage: Exploring the role of virtue in communication skills. Journal of Marriage & Family Therapy, 27, 327–340. Griffitt, W., & Hatfield, E. (1985). Human sexual behavior. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman. Halford, W. K., Hahlweg, K., & Dunne, M. (1990). The cross-cultural consistency of marital communication associated with marital distress. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 52, 487–499. Heiman, J. R., & Grafton-Becker, V. (1989).Becoming orgasmic: A sexual growth program for women. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Hulbert, D. F., & Apt, C. (1995). The coital alignment technique and directed masturbation: A comparative study on female orgasm. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 21, 21–29. Kelly, M. P., Strassberg, D. S., & Kircher, J. R. (1990). Attitudinal and experimental correlates of anorgasmia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 19, 165–177. Kilmann, P. R. (1984). Human sexuality in contemporary life. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Kilmann, P. R., Mills, K. H., Caid, C., Bella, B., Davidson, E., & Wanlass, R. (1984). The secual interaction of women with secondary orgasmic dysfunction and their partners. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 13, 41–49. Leiblum, S. R., & Ersner-Hershfield, R. (1977). Sexual enhancement groups for dysfunctional women: An evaluation. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 3, 139–152. Locke, H. J., & Wallace, K. M. (1959). Short marital adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage & Family Living, 21, 251–255. LoPiccolo, J. (1978). Direct treatment of sexual dysfunction. In J. LoPiccolo & L. LoPiccolo (Eds.), Handbook of sex therapy (pp. 1–18). New York: Plenum. LoPiccolo, J., & Steger, J. C. (1974). The sexual interaction inventory: A new instrument for assessment of sexual dysfunction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 3, 585–595. LoPiccolo, J., & Stock, W. E. (1986). Treatment of sexual dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 760–762. 276 M. P. Kelly et al. MacNeil, S., & Byers, E. S. ( 1997). The relationships between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 6, 277–283. Markman, H. J., Floyd, F. J., Stanley, S. M., & Storaasli, R. D. (1988). Prevention of marital distress: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 210–217. Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1977). Principles of the new sex therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 133, 548–554. McCabe, M. P. (1999). The interrelationship between intimacy, sexual functioning, and sexuality among men and women in committed relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 8, 31–38. McCarthy, B. W. (1995). Bridges to sexual desire. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 21, 132–141. Pierce, A. P. (2000). The coital alignment technique (CAT): An overview of studies. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26, 257–268. Rosen, R. C., & Beck, J. G. (1988). Patterns of sexual arousal: Psychophysiological and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press. Schmaling, K. B., & Jacobson, N. S. (1990). Marital interaction and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 229–236. Strassberg, D. S., & Lowe, K. (1995). Volunteer bias in sexuality research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 24, 369–382. Wheeless, L. R., & Parsons, L. A. (1995). What you feel is what you might get: Exploring communication apprehension and sexual communication satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 12, 39–45. Zimmer, D. (1983). Interaction patterns and communication skills in sexually distressed, martially distressed, and normal couples: Two experimental studies. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 9, 251–265.