* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Secession - DHS First Floor

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Anaconda Plan wikipedia , lookup

Confederate States of America wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee bridge burnings wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee Convention wikipedia , lookup

Fort Fisher wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Roanoke Island wikipedia , lookup

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

Fort Sumter wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

Lost Cause of the Confederacy wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Sumter wikipedia , lookup

Texas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Origins of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Pacific Coast Theater of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Missouri secession wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Secession in the United States wikipedia , lookup

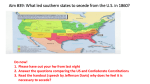

Facts On File: American History Online http://www.fofweb.com/NuHistory/MainPrintPage.asp?ItemI... Close Window secession From: Encyclopedia of American History: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1856 to 1869, Revised Edition (Volume V). Secession was the act by which the 11 Southern states that formed the Confederate States of America withdrew from the Union. The secession crisis of 1860–61 led directly to the outbreak of Civil War. The North's victory in the war ensured that secession would no longer be a political issue of any relevance. There is no provision for secession in the U.S. Constitution. Rather, secession was a concept that developed in response to a series of debates over the course of the antebellum era about the relationship between the states and the federal government. Which held the ultimate power? If the answer was the state, then that entity had the right to secede from the federal government if its liberties were endangered. Three events in particular from the late 18th to the mid-19th century would shape the secessionist position: the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, the War of 1812, and the Nullification Crisis of 1832–33. America's first party system was founded in the 1790s under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson and Hamilton had radically different ideas on the nature of government. Hamilton, a Federalist, favored a strong national government, while Jefferson, the founder of the Democratic Party, was committed to the supremacy of the states. He articulated his position in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, in which he invented the term nullification to describe a state's right to overrule the federal government. The Constitution, argued Jefferson, was a "compact," or agreement, between the states and the national government. If the compact was seriously violated by the federal government, the states could legally withdraw, or secede, from the Union. The first time states threatened to secede was during the War of 1812. Most New Englanders were opposed to the war, largely because Great Britain was the most important market for their manufactured goods. In 1814 representatives from the states of New England held a convention in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss their grievances. Disunion was mentioned prominently on the convention floor. Ultimately, the issue was tabled after the war's end. The question of secession again appeared in 1832 when the federal government adopted a tariff, or tax, on imported goods that Southerners felt was far too high. This was the third time in eight years the government had adopted a tariff that was contrary to Southern interests. In response, the South Carolina legislature passed an ordinance that nullified the federal tariff and stated that if the national government enforced the collection of the tariff, South Carolina would secede. The situation was resolved with a compromise tariff that South Carolina agreed to accept. Temporarily, the storm subsided, but the nullification crisis had major long-term implications for making the Palmetto State a leader of secessionist sentiment. Most importantly, South Carolinian John C. Calhoun emerged from the crisis a powerful voice for states' rights and the protection of slavery. Calhoun was a 1 of 4 9/8/13 2:26 PM Facts On File: American History Online http://www.fofweb.com/NuHistory/MainPrintPage.asp?ItemI... former nationalist who served in the House, the Senate, in the cabinet as secretary of war and secretary of state, and as Andrew Jackson's vice president. In the 1830s, he turned his formidable intelligence to constructing a rationale for ensuring the perpetuation of slavery in a Union he perceived to be increasingly hostile to the minority slaveholders. Rejecting the current two-party system, Calhoun advocated a Southern sectional party based on states' rights that would be devoted to protecting that region's "peculiar institution." Failing to persuade his fellow Southerners to abandon the Democratic Party, Calhoun became increasingly pessimistic about the fate of the South within the Union. For him, secession was a logical and legal process should it become necessary. By the 1840s, Southerners influenced by Calhoun had developed an intellectual justification for secession. The 1850s brought constant conflict over the future of slavery. Most Southerners felt that it was important that slavery expand to the territories to sustain the balance of power between slave and free states in the federal government. Many believed that slavery should be legal everywhere in the nation, even in Northern states that had banned the institution. The majority of Northerners felt very differently. They were willing to allow slavery to remain where it already was but wanted to reserve the territories for free labor only. In response to this attitude, a small group of rabid secessionists, called fire-eaters, began to advocate loudly the dissolution of the Union in order to defend and preserve slavery and states' rights. In 1860 Abraham Lincoln was elected president on a Republican platform committed to stopping the spread of slavery in the territories. Prominent fire-eaters, such as William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama, Edmund Ruffin of Virginia, and Robert Barnwell Rhett Sr. of South Carolina, saw Lincoln and the party he represented as deeply hostile to Southern slaveholding interests. Throughout the fall and winter of 1860 they worked hard to dissolve the Union. They had compelling arguments, all of which centered on the Republicans' desire to use the federal government's power to deny the property rights of Southerners. The fire-eaters faced significant obstacles. The wealthy states of the Upper South like Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky were not interested in seceding. They wanted to watch and wait to see if they could forge a compromise that would be to their advantage. In the Lower South, it was not clear that the majority of nonslaveholding farmers were willing to support secession to save an institution they had no financial stake in preserving. There were also a substantial number of "cooperationists" in the lower South that favored continuing negotiations with the federal government. They argued that secession should be seen only as a last resort. Southern radicals knew that they had to manage things very carefully or they would lose their momentum and secession would fail. The fire-eaters chose to focus their attentions on South Carolina, in hopes that the state's leaders could be convinced to secede quickly and decisively. The Palmetto State was a natural choice to lead the secession movement. It had been the home of John C. Calhoun and a center of secessionist sentiment for more than three decades. Beyond that, South Carolina's constitution was unusual in that it required the state legislature to choose presidential electors. As such, when Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, most Southern legislatures had adjourned for winter, but the South Carolina legislature was still in session pending the results. They immediately approved Governor William Henry Gist's call for special elections to choose representatives for a secession convention. South Carolina's secession elections made the state's departure from the Union a certainty. Strong opponents of secession declined to run for seats at the convention, knowing that they would be defeated. Cooperationists dismissed the convention as largely meaningless, 2 of 4 9/8/13 2:26 PM Facts On File: American History Online http://www.fofweb.com/NuHistory/MainPrintPage.asp?ItemI... believing that secession would only happen if a group of Southern states agreed to secede together. When the secession convention was seated on December 17, 1860, it was populated entirely by fire-eaters. A committee was appointed to draw up a secession resolution, and in short order they completed their work. The convention voted unanimously on December 20 to endorse the resolution that declared the union between the states to be "dissolved." South Carolina's bold move gave a big boost to the efforts of fire-eaters in the other states of the Lower South. In each state, the same basic pattern had to be followed: elections, a secession convention, and the adoption of an ordinance of secession. In no state was secession as much of a certainty as in South Carolina, and in some states the issue was hotly contested. However, the inspiration provided by the Palmetto State, as well as skillful politicking by fire-eaters, eventually convinced the rest of the Lower South to join South Carolina in seceding. By February 1, 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had called secession conventions and voted to leave the Union. On February 4 delegates from the seceded states met to begin drawing up a constitution for the new nation. The states of the Upper South hesitated much more than those in the Lower South. Pro-Unionist sentiment, Northern commercial ties, and a much lower number of slaves made secession more problematic. For the federal government, the key to retaining the loyalty of the Upper Southern states was a noncoercive policy. Compromise between North and South was discussed and rejected, and as time dragged on, hope faded. Supplies began to run out for the small Union garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, located in Charleston Harbor. President Lincoln weighed his options, keenly aware that popular sentiment in the North heavily favored resupplying the fort and keeping it under the national flag. On April 6 Lincoln went public with his decision to resupply Fort Sumter, but only with food and other necessities of survival. President Jefferson Davis could not abide by this decision, as he was well aware of the symbolic importance of allowing the North to keep possession of the fort. So, Davis decided to fire upon Sumter before the Northern ships arrived. On April 12, 1861, Confederate batteries attacked, and the Garrison surrendered two days later. Lincoln responded to the attack on Fort Sumter with a call for 75,000 troops to put down the insurrection. At this point, the states of the Upper South had a choice between taking arms against the South and taking arms against the North. This was an easy decision to make, and shortly thereafter Virginia left the Union. Over the course of the five weeks after Fort Sumter, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina followed suit. The secession crisis had ended and the Union was dissolved. The stage was set for the bloodiest conflict in American history. William C. Davis, Rhett: The Turbulent Life and Times of a Fire-Eater (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001); Charles B. Dew, Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001); 3 of 4 9/8/13 2:26 PM Facts On File: American History Online http://www.fofweb.com/NuHistory/MainPrintPage.asp?ItemI... William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion: Secessionists at Bay, 1776–1854 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990); William A. Link, Roots of Secession: Slavery and Politics in Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Kenneth M. Stampp, And the War Came: The North and the Secession Crisis, 1860–1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1970). Text Citation (Chicago Manual of Style format): Bates, Christopher. "secession." In Waugh, John, and Gary B. Nash, eds. Encyclopedia of American History: Civil War and Reconstruction, 1856 to 1869, Revised Edition (Volume V). New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2010. American History Online. Facts On File, Inc. http://www.fofweb.com/activelink2.asp? ItemID=WE52&iPin=EAHV257&SingleRecord=True (accessed September 8, 2013). Other Citation Formats: Modern Language Association (MLA) Format American Psychological Association (APA) Format Additional Citation Information Return to Top Record URL: http://www.fofweb.com/activelink2.asp? ItemID=WE52&iPin=EAHV257&SingleRecord=True 4 of 4 9/8/13 2:26 PM